OKC's development has the vibe of the '80s oil boom. Are we destined for another bust?

Promises of stunning skyscrapers and a major new amusement park. Local dealerships selling Porsches and Jaguars. Celebrity sightings. Restaurants catering to patrons who can afford $1,000 dinners. It’s 2024. Or is it 1980?

Economists say the good times currently underway in Oklahoma, especially in Oklahoma City, are not fleeting or built on shaky ground as they were during the oil boom that created fortunes that went bust in the early 1980s. But some who were around during that oil boom admit the vibe of today’s era feels awfully familiar.

Kyle Anderson remembers his grandfather, Norton Standeven, reflecting on the free spending days of the early 1980s and how it compared to the 1920s. His warning: “This will come to an end and it won’t be pretty.”

Anderson, a private chef, isn’t convinced the same dire outcome is possible this time around, but adds the atmosphere is familiar.

“We’ve all danced at this wedding before,” Anderson said. “There is an amazing amount of cash being spent.”

Just in Oklahoma City, developments once unthinkable — a $400 million resort along the Oklahoma River and a $1 billion industrial park — are already under construction. More than $200 million is being spent on the mixed-use OAK development across from Penn Square Mall. The downtown skyline is changing with four mid- to high-rise buildings topping out in recent months.

The list of what is still coming and proposed is even more stunning.

Oklahoma City is set to spend $1 billion on a new arena and stadium.

A California businessman says he’s serious about building a $1.5 billion multi-tower development in Lower Bricktown that is to include the country’s tallest skyscraper. And a Colorado developer says he is going to build a 12,500-seat amphitheater but at a new location after his first choice was denied by the Oklahoma City Council.

Elsewhere in Oklahoma, the small town of Vinita is wondering if it will truly become home to a $2 billion amusement park. Cushing is awaiting word on what’s next with a planned $5.6 billion oil refinery.

Then and now: OKC projects from the 1980s that look an awful lot like projects today

What’s going on? And can the past provide a hint at what to expect?

A city built on big dreams

Oklahoma City’s first boom took place on Day One when several thousand settlers rushed to stake their lots on prairie land along what was then the North Canadian River. The city quickly built up over the next several years, and by the early 1900s, it boasted a streetcar system, amusement park and visions of an elaborate park system and of course, being named the capital of the future state.

Big plans also went bust early and often.

The city was less than a year old when civic leaders Henry Overholser and C.G. “Gristmill” Jones launched a community fundraiser to build a six-mile “grand canal” to create electricity and power a flour mill. The canal failed within days of opening.

The city’s first amusement park, Delmar Gardens, opened in 1902 and, inspired by New York’s Coney Island, featured a boardwalk along the river and a 3,000-seat theater and dance pavilion, a horse track, baseball field, zoo, beer garden, swimming pool, a penny arcade, a wedding chapel, hotel and restaurant.

It closed in 1910 due to the start of prohibition and flooding along the river.

Even the state Capitol fell short of big dreams, which originally included a dome and an elaborate arch spanning Lincoln Boulevard at NE 16. The arch was never built. The Capitol building went with a flat roof until the dome was finally constructed as part of the 2007 Centennial celebrations.

An array of ambitious office buildings, each taller than the next, were announced in waves starting in 1910 and then again in the 1920s. Economic downturns led to the cancellation or reduced scale of several projects during both construction sprees.

Some of the most audacious proposals started popping up during the oil boom of the late 1970s and early 1980s that attracted a tidal wave of outside investment. David Rainbolt, executive chairman of BancFirst, was a young lending officer who saw the rush of money coming into Oklahoma.

“There was capital from around the world coming into Oklahoma,” Rainbolt said. “The velocity of that cash here in the state was unbelievable. The infrastructure for investment — oil and gas, real estate — was nowhere big enough to absorb that kind of international cash flow. The excesses were gigantic.”

More: Legends Tower: Could the tallest skyscraper in the US withstand Oklahoma's tornadoes?

Oil and gas was the economic driver for both Oklahoma and Oklahoma City. Keaton Cudd had a front-row seat to the rise and fall of an array of endeavors as chief economist at Kerr McGee from 1978 to 1981 and then as a vice president at Amarax from 1981 to 1983.

“The environment in the late ‘70s on a national basis was not the greatest in the world for bank lending,” Cudd said. “There weren’t that many borrowers the banks could bring in to place the money they had available.”

Skyscrapers, amusement parks, grandiose homes, expensive cars and trips abroad were all doable at the time thanks to an eagerness by banks to get a foothold in a state where the oil and gas industry was seen as an unending economic boom.

Much of that money flowed through Penn Square Bank. Cudd worked with Bill “Beep” Jennings at Fidelity Bank before Jennings turned Penn Square Bank from a small shopping center outlet into a financial powerhouse.

He grew the bank by generating large numbers of energy loans of which only a fraction were kept at Penn Square Bank while the remainder were sold to larger banks across the country.

The bank’s holdings grew from $35 million to $525 million in less than a decade while deposits grew from $29 million to $470 million.

Cudd recalled overhearing a conversation in which a plumber, landscaper and clothing salesman discussed the performance of their oil well investments.

“Everybody felt like they could do pretty much what they wanted to,” Cudd said. “And they were right. Funding was endless. Everybody was getting into it. They would go down to their local bank and got a letter of credit.”

During this time, Charles Givens bought a former orphanage at NW 63 and Pennsylvania Avenue and built Waterford, which for years would be among Oklahoma City’s priciest mix of housing and offices, along with an upscale hotel. Oak Tree Country Club, another symbol of the city’s rising wealth, opened in 1980.

A Dallas developer, Vincent Carrozza, built Oklahoma Tower, Corporate Tower and what is now the headquarters of Continental Resources. Other additions to the downtown skyline at the time included Leadership Square while other high rises were built in northwest Oklahoma City, including the 22-story Valliance Bank Tower and the 18-story Union Plaza.

Rainbolt got a hint in 1981 of the crash that was to follow when at a conference he met Phillip Zweig, an author doing research for an article about oil and gas lending.

“I didn't know who he was,” Rainbolt said. “We were chit-chatting, and he told me he was writing an article about Penn Square Bank. He had inkling things were out of control. At that point the bank hadn’t failed yet. His article would have been ‘This bank is out of control, this oil boom is out of control.’”

An array of ambitious projects came to a halt, including a skyscraper north of the Skirvin Hotel and another at the northeast corner of Broadway and Sheridan. Oklahoma Gas and Electric Co. scrapped plans to build a new high-rise headquarters at the northwest corner of Harvey and Robert S. Kerr.

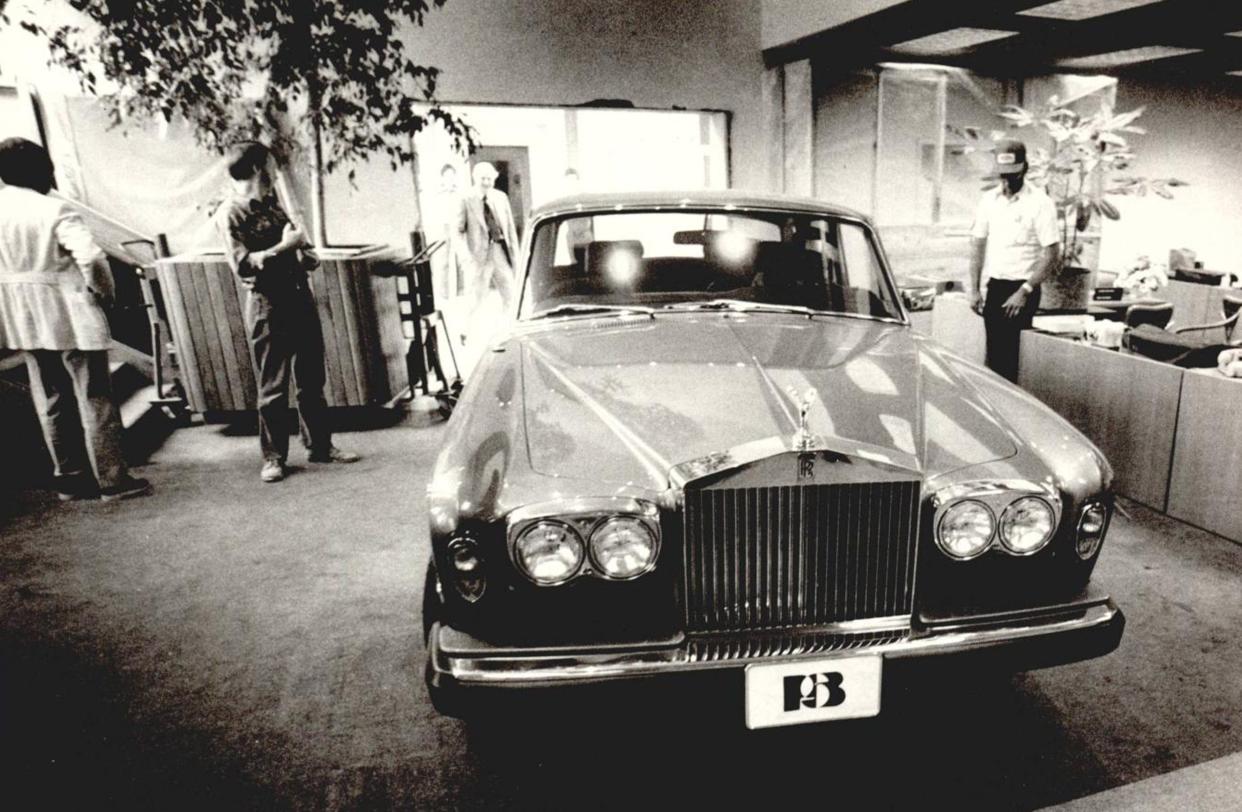

Carrozza dropped plans to build a Galleria shopping mall where Devon Energy is now headquartered. Developers spent years preparing plans to build a $100 million Seven Continents amusement park on 2,000 acres northwest of Stroud only to see the property end up being sold at auction in 1981.

Cudd also saw the bust coming. Amarax was headquartered in the Colcord building (now the Colcord Hotel) and was planning to build a west wing to the landmark that was planned by Charles Colcord but never built.

“We all saw this collapse coming,” Cudd said. “We tried to sell as many airplanes and ski lodges as we could and get money in the bank.”

![In this 1979 file photo, developer Vincent Carrozza shows a model of his proposed downtown Galleria project. [Paul B. Southerland/The Oklahoman File]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/lvJdiPYAOSlcGDbLCvrbgA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD0xMzI1/https://media.zenfs.com/en/aol_gannett_aggregated_707/a89c5248e8c8dd30fc5689a51554d6cb)

Cudd saw an opportunity to do similar work as a consultant and distributed 135 flyers to oil companies in Oklahoma City offering to help them sell off unneeded assets. That was in April of 1982, and the flyers drew zero interest.

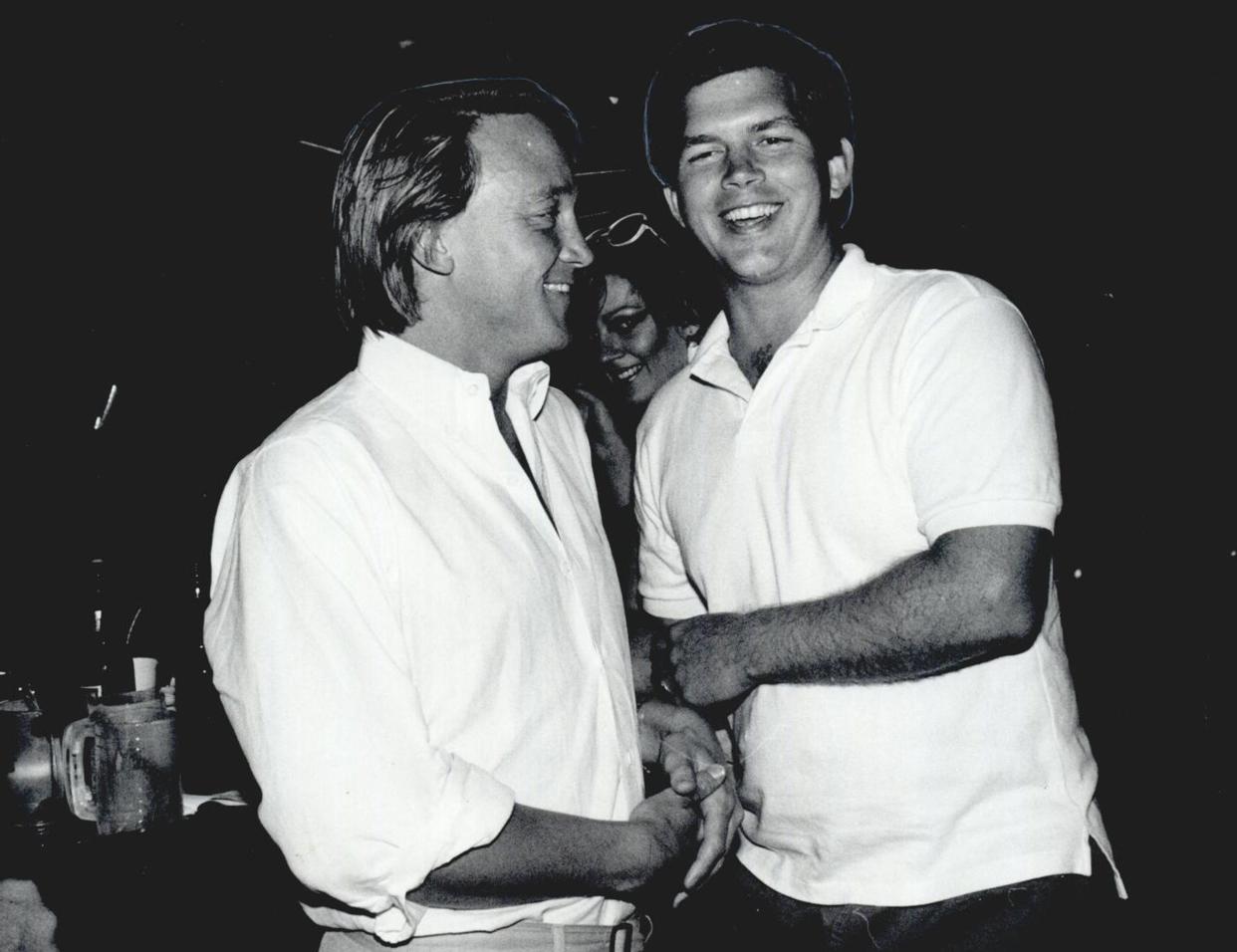

Penn Square Bank failed on July 4. The collapse rattled the national banking system and ended the party in Oklahoma City. Cudd’s sleepy consulting start-up drew up contracts with 17 companies the day after the bank failure.

Zweig’s article turned into a best-selling book, “Belly Up.” Bumper stickers that read “Drive fast, freeze a yankee” during the height of the boom were replace with bumper stickers pleaded “Lord, give me one more boom. I promise not to screw it up.”

Dreaming big is back in Oklahoma City

Once again, big dreams are being pitched with some well on their way to becoming reality.

OKANA, the $400 million resort being built by the Chickasaw Nation along the south shore of the Oklahoma River, is set to open next year. The resort, visible to thousands of daily travelers along Interstates 35 and 40, includes a 404-room, 11-story hotel, a 100,000-square-foot water park, a 12,000-square-foot family entertainment center, a spa, golf simulator and 36,000 square feet of retail and dining options.

At least $200 million is being spent by developers Ryan McNeill and Everett Dobson on OAK, a mixed-use development at 5101 N Pennsylvania Ave. that includes a 132-room boutique Lively Hotel, 320 apartments, and an array of upscale restaurants and retail. It is set to open later this year.

The future $150 million new headquarters for Locke Supply is under construction at Interstate 240 and Bryant Avenue as part of the $1 billion OKC 577 being developed by Richard Tanenbaum and Mark Beffort. Plans also include construction of an array of industrial buildings and offices, sidewalks, bike paths, picnic areas, space for food trucks, basketball and pickleball courts, and wetlands.

Tanenbaum and Beffort also are building Convergence, a $195 million high tech development that includes an office tower, lab space, restaurants, bars, shops and a 107-room hotel at the gateway to the city’s Innovation District.

Construction is well underway on three downtown office buildings, including the $65 million, 12-story Citizen tower at NW 5 and Robinson Avenue that will include hotel suites, offices, a private club and restaurant.

The 1980s saw some big civic projects pitched, including a “String of Pearls” park plan along what is now the Oklahoma River and a domed football stadium at the state fairgrounds, that failed to get started despite years of hype.

This time around, the big civic projects include a new NBA stadium and a multi-use soccer stadium. And unlike the 1980s projects, construction is highly likely with a mix of public and private funding.

Four large downtown Oklahoma City developments are set to start this summer.

The Hub, consisting of 292 apartments and a seven-story office building anchored by Core Bank, is set to be built at the northwest corner of NW 13 and Broadway.

Guernsey, an engineering and architectural firm, is set to move its headquarters downtown as anchor of Alley North, a $115 million development at the northeast corner of NW 13 and Broadway.

Alley’s End, a $52 million, 211-unit affordable housing development, will be built at the southeast corner of NW 4 and E.K. Gaylord.

A $27 million redevelopment of the former Stowe’s furniture warehouse at 1 NW 6 is set to include a market hall, apartments and pickleball court. A brewery and greenhouse once planned as part of the project were scrapped when the development was taken over by Pivot Project.

More: A funding tool for OKC development is near its end. Why were some projects chosen over others?

Other big projects are stalled, canceled or have yet to start after years of delays.

Rose Rock Development was first selected in 2018 by the Oklahoma City Urban Renewal Authority to build an eight-story, 265-unit apartment tower at the southwest corner of E.K. Gaylord and the Oklahoma City Boulevard. Developer Steven Watts promised he was “confident” construction would start in spring 2023 after the city council increased TIF assistance from $5.7 million to $21.5 million. The site has stood untouched since but is set to start later this year.

Developer Pat Salame first announced plans in 2017 to redevelop dozens of lots west of Scissortail Park into a mix of housing, offices, retail and restaurants. Despite multiple indicated start dates, site work for Strawberry Fields to date has consisted of acquiring and clearing lots.

Jonathan Dodson, CEO of Pivot Project, recently confirmed plans for a 247-unit apartment complex at NW 4 and Shartel has stalled and the property is up sale. Industry, a $49 million redevelopment of century-old warehouses located between SW 2, SW 3, Shartel Avenue and Classen Boulevard is on hold.

And yet other projects are best described as “wait and see.”

Branson-based Mansion Entertainment announced plans in 2023 to build a $2 billion, 125-acre “American Heartland Theme Park” in Vinita. The company announced it planned to open the park by 2026, but the only work to date is a groundbreaking for an RV park planned as part of the project.

California developer Scot Matteson is on record saying he plans to start construction this summer on three high-rise towers with a Dream Hotel and a mix of apartments and retail. The project has drawn skepticism due to his insistence he is serious about building a fourth tower that if built would be the tallest in the United States.

Texas-based Southern Rock Energy Partners announced last year it was going to build a $5.6 billion refinery in Cushing with construction starting in 2024. The company recently confirmed the start is delayed and was not able to provide a new schedule.

Developer JW Roth hoped to start construction this summer on a $100 million, 12,500-seat amphitheater in west Oklahoma City, but those plans were put into question when the Oklahoma City Council recently denied needed rezoning. Roth pledged to find a new location for the project.

Similar vibes, but improved odds for success?

![Depositors que outside the doors of Penn Square Bank as they wait to try to withdraw money on July 6, 1982. [Bob Albright/The Oklahoman File]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ggk70lZVzpvfTfP0ZbLkug--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD03OTk-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/aol_gannett_aggregated_707/f66783842b5477a09b189df91dad8094)

Oklahoma historian Bob Blackburn agrees with Rainbolt’s assertion that Oklahoma wasn’t set up to absorb the millions of outside dollars that flowed through Penn Square Bank. Now it’s flowing again, but Blackburn adds the source of the cash flow is far more diverse — and local — than it was in the early 1980s.

“Finance is different,” Blackburn said. “People underestimate the impact of Love’s Travel Stops and Paycom. We have an industry now that is not imported. The idea then was ‘Let’s import industry, let’s get Xerox and IBM. Today’s being built from the ground up. And we also have Indigenous tribal enterprises.”

Rainbolt believes lessons were learned from the boom and bust of the 1980s. Maybe enough people kept their promise to God — “just one more boom ...”

“The magnitude of this economy now compared to the projects of 40 years ago are far, far different,” Rainbolt said. “Our infrastructure, our economy is so much larger than it was back then. And it’s much more diverse. We’re far less dependent on oil and gas in terms of state revenues. And it’s less in terms of employment. It’s a lot less.”

Rainbolt said a proxy indicator of the economy driven by the energy industry are the severance taxes paid in Oklahoma — revenues collected on the extraction of non-renewable natural resources that are intended for consumption in other states. Those taxes represent about 7% of state revenues, Rainbolt said, compared to almost 27% in 1981.

Rainbolt sees the investment in 2024 is better aligned with the size of the Oklahoma economy.

More: How are Oklahoma's oil and gas companies faring amid market volatility?

“Our economy is growing from multiple sources now, not from a single source as it was back in the ‘80s,” he said. “A third of the banks failed in the ‘80s. The bankers are better bankers now.”

That’s not to say Rainbolt believes all the large projects announced across the state are destined to be reality.

“Those sort of projects are always discussed, and in almost any economy in every state,” Rainbolt said. “If they happen, nobody will be happier than me. But you’ve got to look at those extraordinarily large projects and always know there is risk attached in any economy.”

Those interviewed by The Oklahoman agree the excessive spending seen 40 years ago is once again on the rise. There are those who believe American Heartland Theme Park is the next Seven Continents Amusement Park, or that new skyscrapers shown in renderings may be just as elusive as those drawn up in the early 1980s.

“We look at our kids, now in their 40s, and wonder how they are making so much money?” Blackburn said. “There is a lot of money being made in finance and the tech world.”

Blackburn believes Oklahoma City’s embrace of self-investment with the MAPS initiatives triggered a change in the city’s DNA. That investment is often cited by outside developers investing in Oklahoma. Oil and gas, Rainbolt said, is no longer creating an environment for the boom and bust of big dreams. And the consequences of such busts are no longer seen as potentially devastating for the state’s economy.

“Oklahoma lenders financed a lot of the boom here in Oklahoma in the ‘80s,” Rainbolt said. “The debt capital for the projects being talked about now is not coming from Oklahoma financial institutions. The consequences of those projects possibly not turning out as planned won’t fall on our banking system the way they did in the 1980s.”

Steve Lackmeyer started at The Oklahoman in 1990. He is an award-winning reporter, columnist and author who covers downtown Oklahoma City, urban development and economics for The Oklahoman. Contact him at slackmeyer@oklahoman.com. Please support his work and that of other Oklahoman journalists by purchasing a subscription today at subscribe.oklahoman.com.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: OKC development, skyscraper plans feels a lot like '80s oil boom