Official: Phoned-in threat said bomb was in chambers of judge overseeing Murdaugh trial

Alex Murdaugh’s double-murder trial was abruptly delayed on Wednesday after an anonymous caller phoned in a bomb threat targeting Judge Clifton Newman’s chambers at the Colleton County Courthouse.

An official, given anonymity so they could speak freely, said the threat was phoned in to the county clerk of court’s office general session’s line. The threat specifically said a bomb was in Newman’s chambers, a highly secure area on the courthouse’s second floor, the official said. The threat was phoned in by a man speaking in a low voice, the official added.

Murdaugh is on trial in Colleton County for the June 7, 2021, murders of his wife, Maggie, and youngest son, Paul, at the family’s 1,700-acre rural estate, called Moselle. Murdaugh has pleaded not guilty.

If convicted, he faces life in prison without parole.

The courthouse was evacuated just as Brian Hudak, a computer forensics specialist with the State Law Enforcement Division and the state’s 38th witness, took the witness stand midday Wednesday. Newman brought the proceedings to a halt, dismissing the jury, then the public, which included a University of South Carolina journalism class.

“Ladies and gentlemen, at this time we have to vacate the building,” Newman said in a loud, but unruffled voice.

Minutes after the evacuation, SLED confirmed Colleton County Courthouse personnel received a bomb threat.

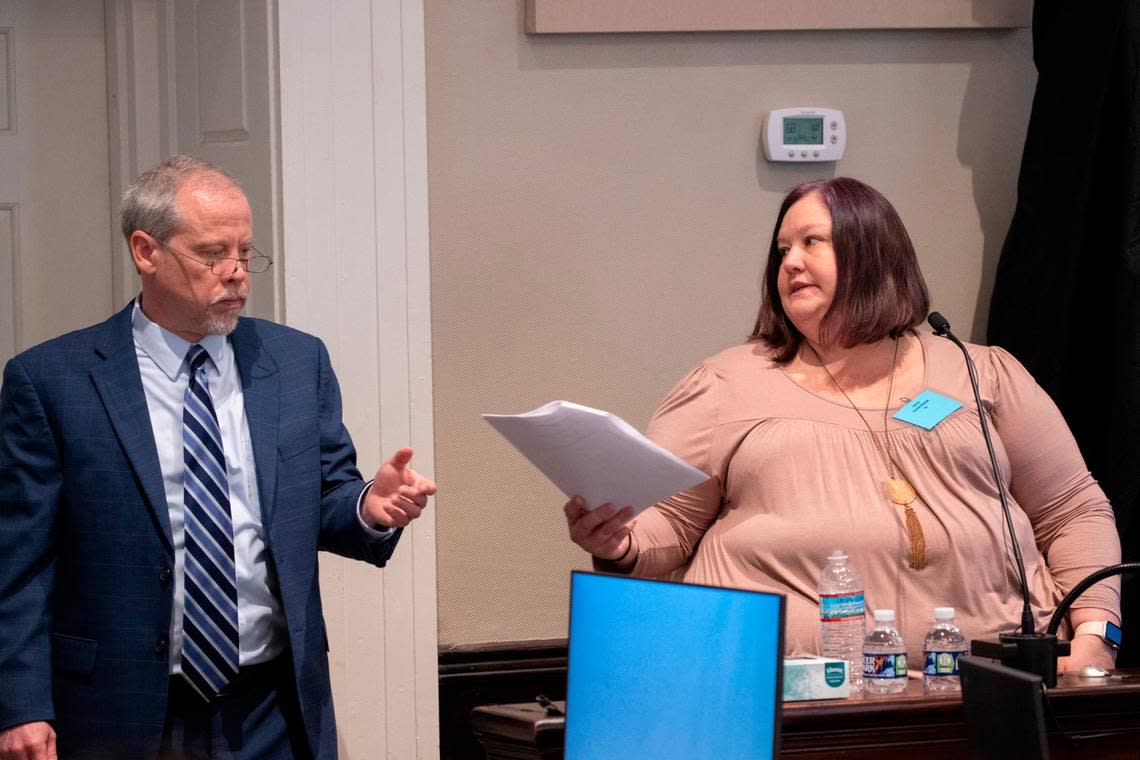

Hudak was the state’s third witness Wednesday, after the 12-member jury heard from two witnesses — Annette Griswold, Murdaugh’s former paralegal, and Michael Gunn, a principal at Forge Consulting, a firm Murdaugh used for his alleged thefts — who both testified to Murdaugh’s alleged financial crimes.

A fourth witness, FBI special agent Dwight Falkofske, took the stand last to testify about data pulled from Murdaugh’s Chevrolet Suburban. His testimony will continue Thursday.

The data, which recorded every time Murdaugh put his SUV into “park” gear the night of June 7, 2021, and then took it out of “park,” took the FBI more than a year to decode because it was encrypted, Falkofske testified, responding to state prosecutor John Conrad.

The car’s forensic record largely confirmed a generally agreed upon timeline the prosecution has already established for the the night of the killings through call records, forensic cellphone evidence and testimony from his mother’s caregiver, Mushelle “Shelley” Smith.

The evidence from Murdaugh’s car supports the narrative that Murdaugh left the Moselle property around 9:06 p.m. before driving to his mother’s home in nearby Varnville. Smith said Murdaugh spent 20 minutes with his mother, before driving back to Moselle around 9:45 p.m. Smith testified, however, that days after June 7, 2021, Murdaugh told her he had been at his mother’s house “30 to 40 minutes.”

Murdaugh called 911 at 10:06 p.m. after finding Maggie and Paul’s bodies near the kennels, which his car recorded as a Bluetooth call, Falkofske said.

Murdaugh’s ex-paralegal says she discovered missing money

Wednesday’s most riveting testimony came from Griswold, a paralegal who worked for Murdaugh at his former law group, then known for short as PMPED. She started her job, at what is now called Parker Law Group, in July 2012.

For years, Griswold, a single mother, handled Murdaugh’s most complex cases — a job that included preparing financial disbursement statements of who was to get expenses, awards and fees after Murdaugh won or settled a legal case, she told lead prosecutor Creighton Waters.

After working for Murdaugh at his family law firm for nine years, Griswold said she was used to Murdaugh’s disorganization.

Murdaugh, she testified, would insist that no one touch his messy office, and he had a habit of showing up to work late and staying late, leaving his keys in his car and taking two phone calls at once, at times holding both phones up to his ear.

He was highly productive and full of energy, Griswold said.

“He was a Tasmanian devil,” Griswold said. “He would just start spinning, coming through, shouting everybody’s name, ready to get work done right when he walked in through the door.”

Over the course of her work, for months in 2020 and 2021, Griswold testified she knew something was wrong with some of Murdaugh’s disbursement statements. She feared coming forward, however, because of the wide respect for Murdaugh, whose family founded the Hampton firm, she testified.

In late 2020, Griswold testified Wednesday that a number of incidents of missing money alarmed her.

Summoning up the courage, Griswold collected materials on questionable distributions of money designated for Murdaugh to show her supervisors, she said. Griswold testified that when her daughter learned of the plan, she told her mother, “You need to get your resume together, because when you turn this in they’re going to fire you.”

In hindsight, Griswold said that she should have seen the warning signs.

Murdaugh would insist that she write checks to Forge, rather than Forge Consulting, a structured settlement firm employed by PMPED and other lawyers in South Carolina. Murdaugh, she said, told her that Forge was one of a number of small companies “under the umbrella” of Forge Consulting.

In reality, the Forge account was a Bank of America account controlled by Murdaugh, and falsely labeled “Forge” on the checks, multiple witnesses — from Forge principal Gunn to Murdaugh’s former law firm chief financial officer — testified.

On the stand Wednesday, Gunn said Forge stopped using Bank of America four years ago, and Murdaugh did not have permission to use their name.

After court, Gunn released a statement, which reads, in part, “Forge Consulting has been in business for over 20 years building our reputation on professionalism, experience and integrity. We’ve built our business on the truth and that’s exactly why we’re here today: to tell the truth.”

He continued, “I don’t know what happened that horrible night in Islandton when Maggie and Paul Murdaugh were murdered. But I do know that Alex Murdaugh used our good name to defraud his clients, his law firm and countless others. I know that Bank of America could have stopped it all there with a single phone call to verify the truth. Unfortunately, that call was never made. I wonder how much tragedy could have been avoided if it was.”

Gunn also said in his statement that he and his attorneys from Strom Law Firm were preparing to take legal action in response to the harm done to Forge by Murdaugh and the Bank of America.

The breaking point for Griswold, she said, came when she went looking for a $792,000 fee that was supposed to be paid to the firm following a case, Faris v. Mack Trucks, that Murdaugh tried in court with his friend, attorney Chris Wilson. Fees are supposed to be paid to the law firm, not to an individual attorney.

Wilson’s paralegal told Griswold that the fees had been paid in March 2021, Griswold testified. But when Griswold asked Murdaugh about the fees, she said Murdaugh shooed her away, saying he never received the checks. They were still in Wilson’s trust account, Murdaugh told her, she said.

“I’m still hoping that he just lost the checks and this is all a misunderstanding, but in the back of my mind there’s this huge red flag saying this isn’t right,” Griswold said.

Griswold eventually approached the firm’s CFO Jeanne Seckinger, who decided to raise the matter with Murdaugh.

“At this point, we wanted to prove that the suspicion we had was wrong and everything is OK,” Griswold testified Wednesday. “We wanted our suspicion to be wrong.”

On June 7, 2021, Seckinger confronted Murdaugh about the missing money.

The conversation was cut short after Murdaugh received a call that his father, Randolph, was in poor health at the hospital. Later that night, Murdaugh’s wife and son were murdered, plunging the whole firm into fear and confusion, Griswold testified.

“We were scared,” Griswold said. “Was it a client? Was it aimed at Alex or the firm? We didn’t know. Just a million thoughts running through our heads.”

The firm rallied around Murdaugh and his brother, Randy, who also worked at the firm, Griswold said.

“We were in complete mama bear mode,” Griswold said, remembering how they started locking the firm’s doors.

Asked whether she continued looking for the Faris fees after the murders, Griswold sarcastically responded, “What Faris fees? That was the furthest thing from my mind.”

On Sept. 2, 2021, Griswold testified she went through Murdaugh’s office, when a check slipped out of a file.

The check, Griswold said, “floated, kind of like a feather to the ground.”

It was a check from Wilson made out to Murdaugh for part of the Faris fee, and it had been deposited at Murdaugh’s fake Forge account at the Bank of America in March, Griswold testified. Murdaugh had repeatedly denied that such a check existed, she said.

Griswold testified that she was hurt and angry and immediately took the check to Seckinger.

“Oh s---, what did you find?” Seckinger asked Griswold, she said.

“This is one of the Faris checks that doesn’t exist” Griswold said, throwing it on the desk.

Murdaugh was fired from the firm two days later.

He later entered rehab for a reported drug addiction after a roadside shooting Labor Day weekend, in which Murdaugh has been charged with insurance fraud. On Sept. 26, 2021, while in rehab, Murdaugh texted Griswold and his other paralegal.

Murdaugh’s attorney, Jim Griffin, asked Griswold read the entire text to the jury.

“Hey, it’s Alex. I finally feel a little better each day. I’m over the worst, but still feel like I have the flu. Real weak. I have been worried about y’all and sorry I didn’t get to tell y’all myself. I know both of you have been hurt badly by me. I know it sounds hollow, but I am truly sorry.

“The better I get, the more guilt I have. I have an awful lot to try to make right when I get out of here. The worst part is knowing I did the most damage to those I love the most.

“I’m not real sure how I let myself get to where I did. I commit to getting better and hope to mend as many relationships as I can. You both are special people and important to me. Please know how sorry I am to make you part of my misdeeds. I hope you are doing as well as possible. I love you very much. ... All my love.”