How This Oceanfront Oasis Became the Most Infamous Mansion in the Hamptons

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

The full story of Grey Gardens is featured in season 2, episode 5 of House Beautiful's haunted house podcast, Dark House.

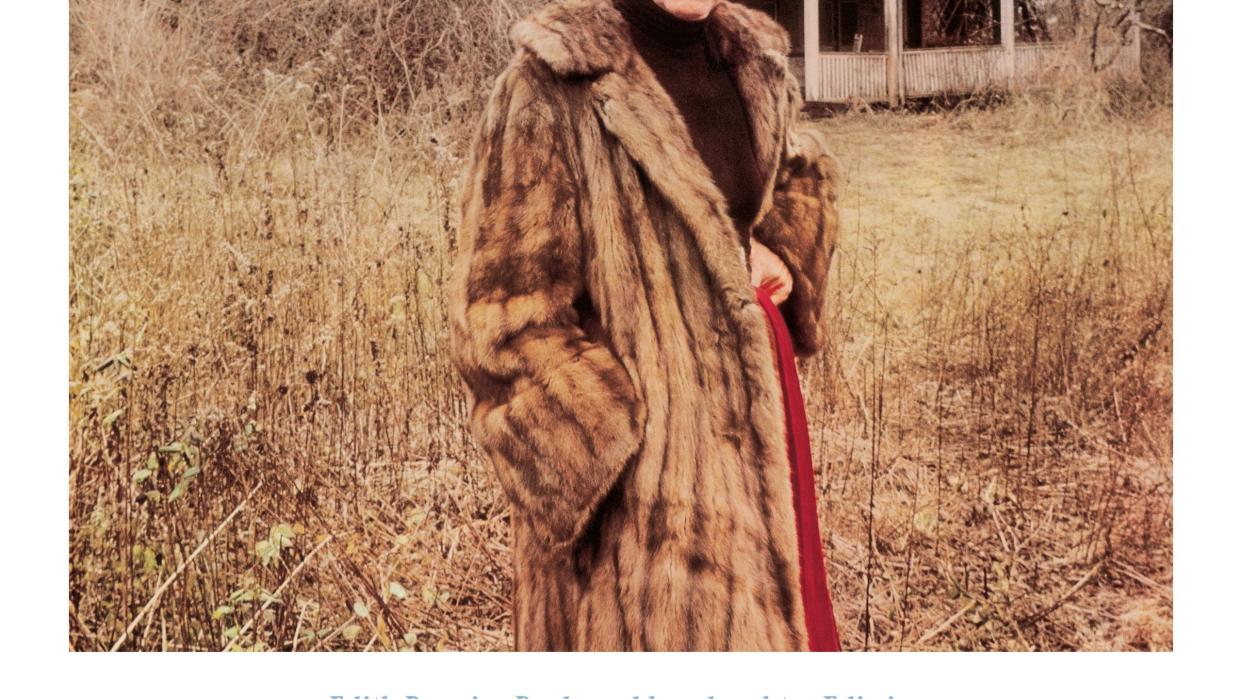

If you pull off the narrow two-lane Montauk Highway in East Hampton in the direction of the Maidstone—the country's ritziest, most exclusive club—and make a few right turns until you find yourself under a canopy of majestic trees, you'll eventually arrive at an unsuspecting American icon: Grey Gardens. A 6,652-square-foot structure perched on the corner of Lily Pond Lane and West End Road, the property is decidedly defiant, a quality undoubtedly shared by the long line of staunch women who have called it home. With a shingle-clad exterior, sage green shutters, diamond-cut Arts & Crafts–style windows, and lush grounds, you may know Grey Gardens from the Maysles brothers' namesake 1975 documentary film, which features the estate at a time when it was veiled in layers of grime and littered with raccoon skulls—or perhaps this is your first introduction to the national treasure.

Occupied at the time by high-society dropouts "Big Edie" and "Little Edie" Beale—aunt and cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis—and their 52 cats, the crumbling mansion came dangerously close to demolition. The home is the subject of countless legends and rumors, but even at its most dilapidated, one could argue that it thrived—and it's certainly thriving today. The great mansion's walls offer far more than just beauty, whispering stories with valuable wisdom about weathering life's inevitable ebbs and flows. But before Grey Gardens found itself in one of the most expensive zip codes in the world and became a sentient Hollywood starlet, it was just a piece of land situated on the Atlantic Ocean. The story starts in the Gilded Age.

The Early Years (1895—1923)

Phillips Ownership

Though its silver screen debut thrust Grey Gardens into the spotlight, the home has been the subject of rumors and gossip since before it was even built. Two years after purchasing the lot at 3 West End Road in 1895, F. Stanhope Phillips and his wife, newspaper heiress Margaret Bagg Phillips, commissioned renowned architect Joseph Greenleaf Thorpe to build their dream home. Amid construction delays due to unforeseen issues securing the property deed, Mr. Phillips died unexpectedly, leaving his large estate to his wife.

Following her husband's untimely death, Mrs. Phillips had his body cremated before officials could perform an autopsy, a peculiar move that sparked widespread rumors among the New York City elite. Among those suspicious was Mr. Phillips's surviving brother, who challenged her control over the estate, claiming she used undue influence on her late husband to obtain it, according to a 1901 New York Times article. Despite these claims, the court ruled in her favor, and the land issues with the East Hampton property were resolved soon after, leading her to build the home in the early 1900s. But by 1913, she had sold it to the president of a coal company, Mr. Robert C. Hill. (This photo shows the cottage before the grounds were developed by the next owners.)

Hill Ownership

Mr. Hill's wife, Anna Gilman Hill, was an acclaimed gardener, and she quickly transformed the grounds of their new summer cottage into a sprawling oasis. Most notably, she imported ornate concrete walls from Spain to enclose the garden, which she filled with climbing roses, lavender, phlox, and delphinium. From her garden, a view of the surrounding dunes, cement walls, and sea mist created a lovely pastel color story that inspired the home's subsequent name, Grey Gardens. The Hills spent 10 happy years there, lovingly maintaining the property before selling it in 1923 to the owners who would ultimately make it famous, Big and Little Edie Beale.

The Bouvier Beale Years (1923—1979)

Meet the Edies

Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale (aka Big Edie) was born in 1895 to an ultra-wealthy judge and his wife. Major John Vernou Bouvier Jr. spread the family mythology that they were descendants of French nobility, a fictional narrative likely propagated out of Gilded Age vanity. Big Edie had three siblings, big brother William Sergeant Bouvier (who died of alcoholism in 1929), little brother John "Black Jack" Vernou Bouvier III (father to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Lee Radziwill), and twin sisters Michelle and Maude Bouvier. They split their time between Lasata, the East Hampton compound that became famous for its connection to Onassis, and their Manhattan family home, which stood on the plot where the famed Carlyle Hotel is today.

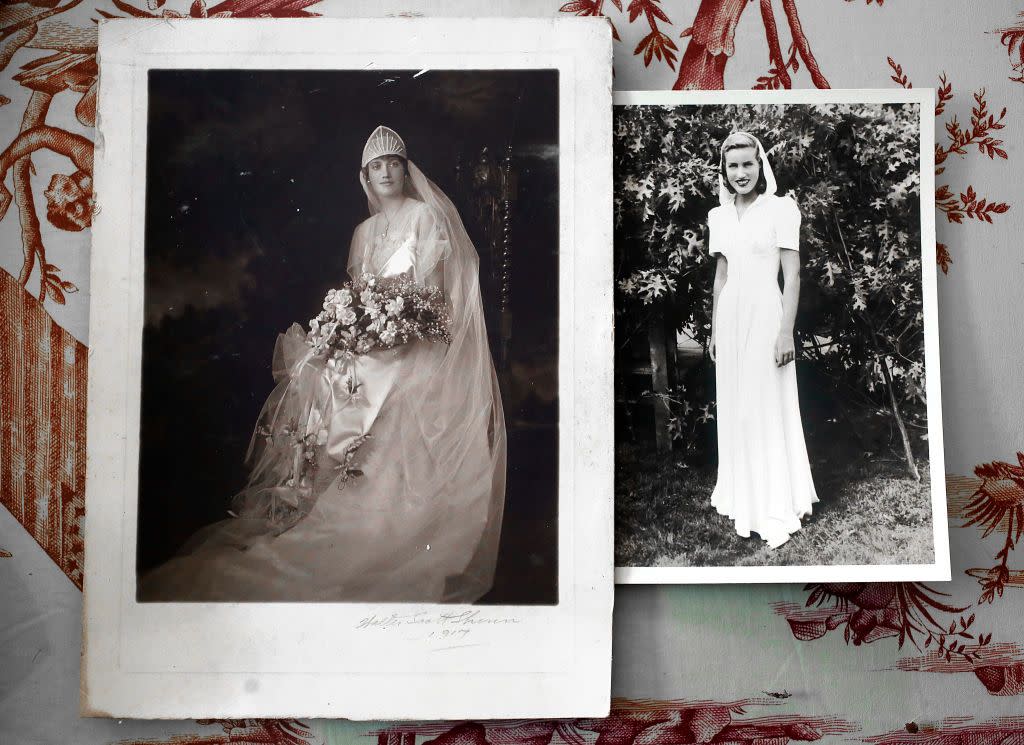

Big Edie was professionally trained as a singer and pianist but was discouraged from pursuing her talents professionally and instead urged to wed. In 1917, when Big Edie was 22, she married 36-year-old Phelan Beale Senior, a future law partner at her father's firm. They moved into an apartment on the Upper East Side, complete with a full staff, including personal chauffeurs (see one of the Beale's 1920s automobiles in front of Grey Gardens). They had three children: Little Edie (1917), Phelan Beale Jr. (1920), and Bouvier Beale (1922). Shortly after their youngest arrived, in 1923, they purchased Grey Gardens.

Big Edie quickly fell in love with Grey Gardens, which allowed her to enjoy a more relaxed and independent lifestyle. She soon began spending all of her summers and most weekends there with the family. Sadly, tension was emerging between Big Edie and her husband, who was embarrassed by her bohemian tendencies, which seemed to evolve further the more time she spent at Grey Gardens. By the early 1930s, the pair had separated, though according to census records Big Edie still employed a household staff, including a live-in cook, a chauffeur, two housekeepers, and a governess.

Meanwhile, Little Edie was 13 and attending Spence, the Manhattan girls' school when her family decided to board her at Miss Porter's, the Connecticut finishing school her cousins Onassis and Radziwill attended. When she graduated in the mid-1930s, Little Edie was presented as a debutante at the Pierre Hotel's ball along with other young women from wealthy and prominent families. Beautiful and vibrant, Little Edie had a lot in common with her mother, including a passion for literature, theater, and performing. She also faced similar scrutiny for these qualities and was raised to believe that her primary value was her marriageability, as she'd need a husband to support her. Throughout the '40s, she continued living in Manhattan, occasionally visiting her mother in East Hampton, and even had a stint in Palm Beach. She also had an affair with the love of her life, Julius "Captain" Krug, a former U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

As Little Edie flourished, Big Edie faced multiple hardships. Her own mother died in 1940, and in 1946, Phelan Sr. made their divorce official through a telegram, after which she received child support and sole ownership of Grey Gardens but no alimony. Then, at her son's wedding, she had a falling out with her father, who claimed he was angry over her "dressing as an opera star." When Major John Vernou Bouvier Jr. died in 1948, his fortune had dwindled, and the majority of his estate went to Big Edie's twin sisters while her (greatly reduced) inheritance was left in the control of her sons. They gave her $300 a month for herself and Little Edie (about $4,500 today), which wasn't enough to employ staff at Grey Gardens. This would eventually spell disaster for the house.

Life at Grey Gardens in 1950s and 1960s

Big Edie had a lover named Gould Strong, who was a musician and likely lived (at least part-time) at the mansion, during the '40s, but they had parted ways by the early 1950s. In 1952, Little Edie continued to pursue a career in show business while living at the Barbizon Hotel in New York City. She even met a famous Broadway producer who invited her to audition for a role—but because Big Edie couldn’t afford to keep supporting her, she returned to East Hampton, missing the opportunity. The circumstances that led each Edie to Grey Gardens point to their divergent attitudes about it: On one hand, it was their last remaining refuge, but on the other, it was holding them—along with their dreams of the stage—captive.

The death of Little Edie's father in 1956 minimized their funds even further, but the mother-daughter duo continued to socialize around East Hampton. At one of their favorite old haunts, the Sea Spray Inn, they met Tom Logan, a former rodeo cowboy whom they invited to live at the house in exchange for help maintaining it. Even with his help, from the outside, passersby could see that the once-tidy gravel driveway was now thickly overgrown and occupied by an abandoned car that looked like scrap metal, a key left in its ignition. Sadly, in 1964 Logan passed away on his cot in the kitchen, either from complications from pneumonia or consumption, and the home deteriorated further.

By the 1960s, the Beales had grown more reclusive and paranoid (though Little Edie left to attend JFK's inauguration), partly because Big Edie was developing arthritis and partly because of a robbery that happened while the two were out at a party. Some 20 years after Little Edie retired to East Hampton, their beloved grand piano was a warped, defunct fossil of its former self, and the entire main level was coated in cat hair, cobwebs, and dust. The mansion had an abandoned quality to it, likely because the women sold some furniture and lived exclusively on the upper floor. By the end of the decade, Grey Gardens stood as a strange dichotomy, straddling extreme wealth and crippling poverty.

Outside Interventions in the 1970s

The Town Raid

In 1971, the town of East Hampton ordered a raid on Grey Gardens, which many considered uninhabitable, and argued that it was a safety hazard. The Suffolk County Board of Health mandated that the Beales clean up Grey Gardens and threatened to evict them if they didn't. According to artist Peter Beard, then boyfriend of Lee Radziwill, the inspectors sprayed a firehose through the house, causing further damage and traumatizing both of its inhabitants. These incidents caught a neighbor's attention, who pitched the story to New York magazine. Once published, Grey Gardens' celebrity fate was sealed.

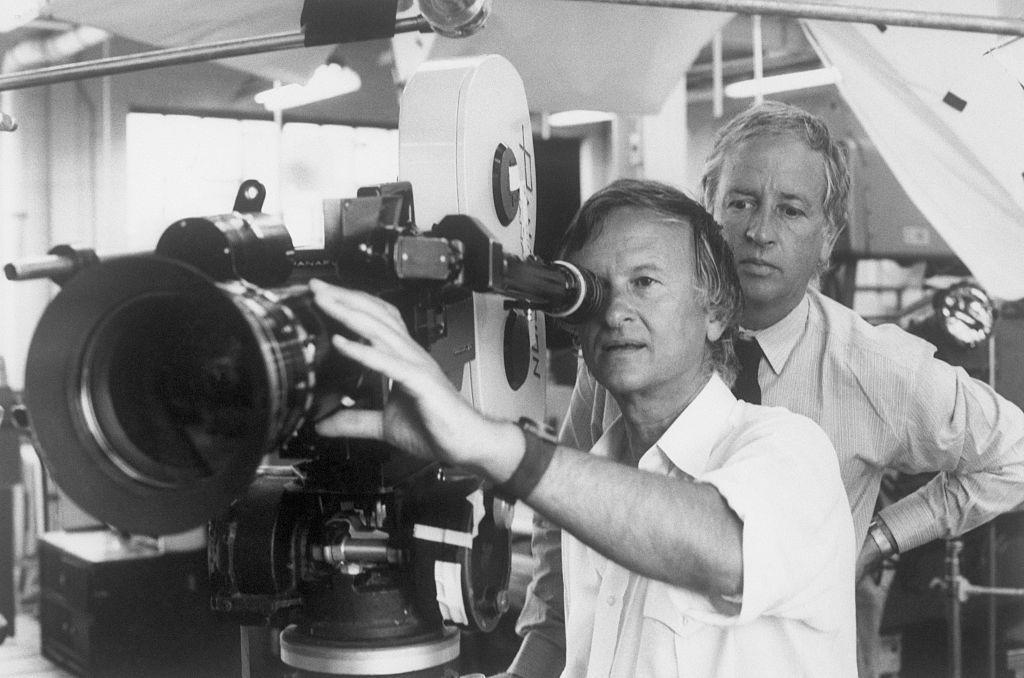

At the time of the raid, Radziwill lived in Montauk, so she and Onassis, along with her wealthy husband, Aristotle Onassis, pitched in to make repairs. Radziwill was also in the process of producing a documentary about her childhood memories at Lasata and hoping her eccentric aunt, with her Long Island lockjaw and beautiful singing voice, would narrate the film. Beard connected her with filmmakers David and Al Maysles, who had released the hit film about the Rolling Stones, Gimme Shelter, in 1970, to help bring it to life. Once introduced to Big and Little Edie at Grey Gardens, the Maysles brothers started filming immediately.

As the footage shows, renovations included installing proper plumbing and heat in a couple of the rooms upstairs, painting over old wallpaper, and essentially bringing the house up to code just enough to pass an inspection. Shortly into the process, the filmmakers decided they had found three stars (the third being the house itself). Radziwill's movie was scrapped (it was released as That Summer in 2018), and the focus shifted onto Big and Little Edie, who were more than happy to deliver Oscar-worthy performances.

The Maysles Brothers' Film (1975)

When filming officially began in 1973, Big Edie and Little Edie had moved two twin beds into one upstairs bedroom that was easier to heat than the primary bedroom. The two did virtually everything in there, including cooking on a small bedside hotplate (and letting their cats nibble off it). Capturing their life in this room and the beautiful landscape surrounding their ramshackle home, the resulting piece is beautiful and funny thanks to Big and Little Edie's iconic campy style but also tragic. Even though Grey Gardens passed its inspection, the conditions were once again bleak, which is evident in the movie. While a few others are captured spending time at the mansion (Brooks, a handyman; Jerry, a young errand boy and companion; and Lois Wright, a local good friend of the family and occasional roommate), the women mostly pass the days alone.

Today, Grey Gardens is widely celebrated as an iconic cinema verité documentary and a revolutionary predecessor of reality television. Shot in a minimalist style sans soundtrack, voiceover narration, reenactments, or staged interviews, it's raw and honest, even voyeuristic and invasive. One gets the sense that the camera is simply observing the women living their lives, totally unprompted, and the house becomes a character in its own right, mirroring the way the women stand out as high-society rebels and refusing to be policed by patriarchal expectations.

The Post-Documentary Years

Of course, with fame comes public scrutiny and attention, so to this day many fans wonder what exactly caused the women to succumb to this lifestyle, aside from transparent eccentricity. There are a few viable theories that attempt to understand them (some of the most compelling being black mold and toxoplasmosis), but it's all armchair theorizing, and we'll never really know what drove the "promising young women" of yesteryear to such unexpected circumstances. Perhaps our desire to diagnose and label them as deviant is worthy of investigation too.

Regardless of why Grey Gardens lost its gilded luster, life went on as usual for a few years after the film wrapped production. During this period, Wright lived with the Beales in the Eye Room, helping feed the animals (namely the cats, who kept the rat problem at bay, and the head honcho raccoon, Buster, whom they believed wouldn't revolt against them as long as he was happily fed) and looking after Big Edie whenever Little Edie went to Manhattan for press events.

But after a bad fall in 1977, Big Edie suffered a badly broken leg, which went untreated. In one of her books about her time there, Wright wrote, "Grey Gardens started to deteriorate. The house wasn't well. It seemed upset. Old houses have feelings." Though friends and family attempted to get Big Edie medical help, she refused, and at the age of 82 she passed away from pneumonia in the hospital. Little Edie didn’t want to sell the home to anyone who was going to demolish it, so she stayed there, traveling to Manhattan for work and even starring in her own cabaret show before moving to California, then Canada, and finally to Bal Harbour, Florida, where she passed away at 84 in 2002.

The Bradlee-Quinn Years (1979—2017)

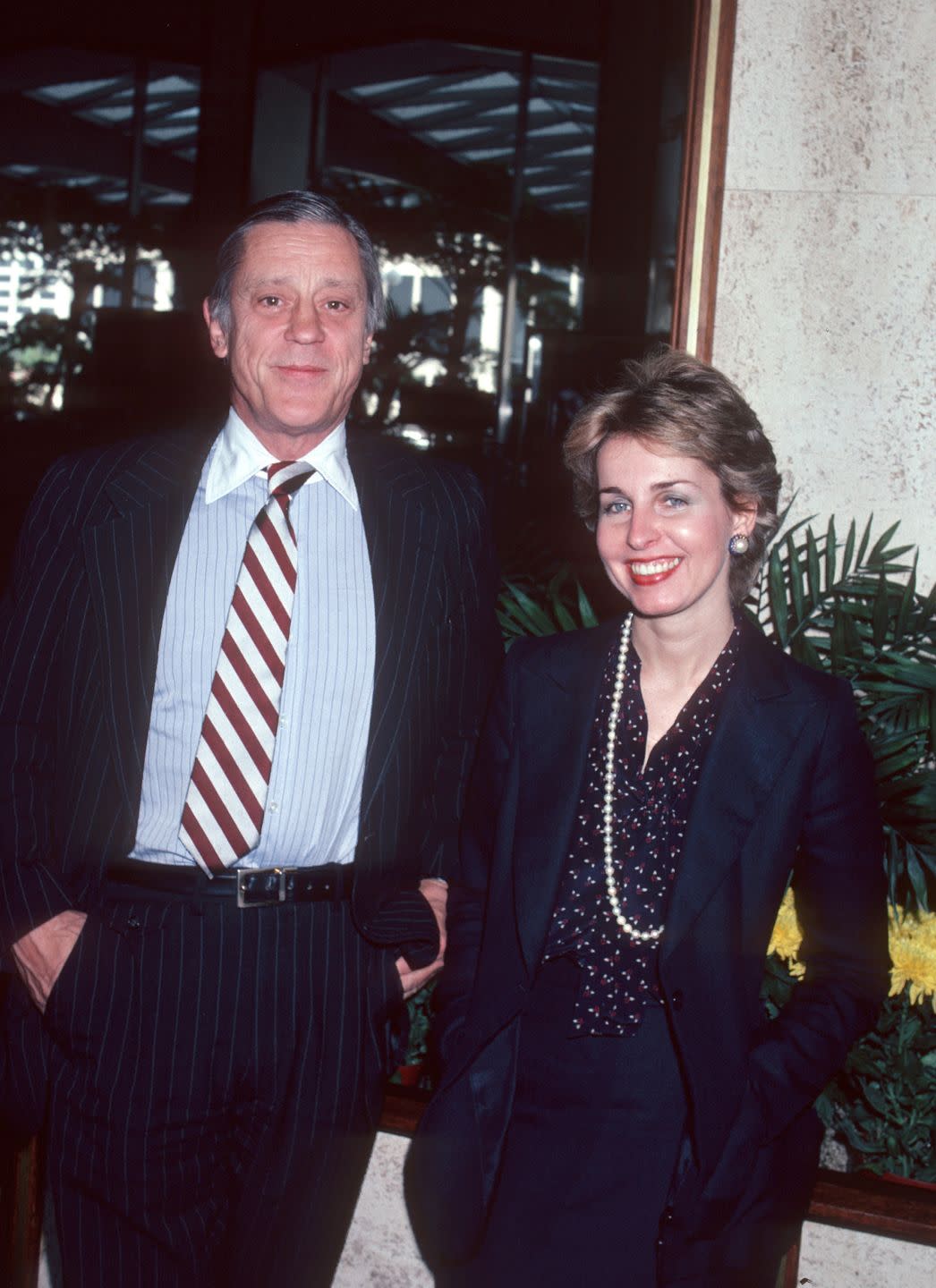

The razzle-dazzle of Grey Gardens cannot be overstated. Even in its disrepair, anyone with an imagination could envision its illustrious potential. In 1979, the writer Sally Quinn and her husband, Ben Bradlee, of Washington Post fame, came to see the ruins, even though the real estate agent refused to go inside with them. Bradlee was allergic to cats and walked out choking within minutes (they would eventually find 52 dead feral cats on the property), so Quinn ventured in on the balmy August afternoon alone. Well, not quite alone.

"Cats were crawling all over, and there were raccoon skulls on the front porch," she tells House Beautiful. And Little Edie was right there with them, "standing on the front porch waiting for me," Quinn adds, with a "sweater wrapped around her waist as a skirt, a scarf on her head, probably because of the fleas, and masses of red lipstick smeared around her face, [when] she said, 'Welcome to Grey Gardens,' as though it was some fabulous palace." As they walked through the front door, Little Edie "did a pirouette and said, 'All it needs is a coat of paint.' There was cat shit all over the walls, and the smell and filth were unbelievable, but we both saw it the way it once was." Able to look past the veneer of very unglamorous things (including literal skeletons), Quinn and Bradlee bought Grey Gardens for $220,000.

There was one more deal to work out: "I told [Little Edie] she could leave it broom clean or she could leave all of the furniture and everything in it," Quinn says. Little Edie opted for the latter, and when Quinn ventured into the attic and "the tiny former maid's room behind the so-called kitchen, [I found] them piled to the ceiling with antiques: wicker chaises, beautiful linens, and china…. I've never been so excited—I even started smoking again," Quinn says, laughing. And so began the restoration process, which, of course, required more than just refurbishing furniture.

It seemed like such a headache that Quinn's friends and loved ones even staged an intervention, but she was determined to finish. Even the contractor said, "'You've gotta tear it down. It would be a lot easier and cheaper to rebuild,'" Quinn recalls. "But then it wouldn't be Grey Gardens, would it? It'd just be another house, or worse, a copy of another house." So, Quinn persuaded everyone to get on board, and the project wrapped in a year. Then she brought the furniture back in, including beautiful iron beds and clawfoot tubs, and everything that couldn't be restored was duplicated to evoke the period. For example, "the curtains in the living room were still hanging but were in shreds, so I took the fabric to a decorator to match them," she says. Thanks to her, Grey Gardens was like a phoenix rising from the ashes, and the Bradlee-Quinn family enjoyed it in all its original glory as a family vacation home until 2017.

The Lange Years (2017—Present)

Quinn sold the home for more than $15 million to Liz Lange (who had rented the property the summer of 2015), a maternitywear designer and creative director of the breezy clothing brand Figue who gained success in the early aughts. Lange is also known more recently for her work on a podcast about her family that she created with reporter Ariel Levy called The Just Enough Family. (Lange describes it as The Sopranos but starring a wealthy Jewish family instead of an Italian one.)

In an interview with The New York Times, Lange reveals that there are still a few remnants from the Beale days, including a plot discreetly tucked away in the garden that reads "Spot Beale: A nobler gentleman never lived beloved by all who knew him died May 29th, 1942." (This photo shows Little Edie with Spot Beale.) Lange worked with designer Jonathan Adler (who also happens to be her best friend from college) and interior designer Mark D. Sikes on the redesign for the house and landscape designer Deborah Nevins on restoring the gardens. You can see Adler's cheeky spin on WASP chintzy style vis-à-vis turquoise shutter paint, blue leopard print wallpaper, and a rattan settee with kelly green cushions, to name a few. Fittingly, the result is, as Adler says, "eccentric American glamour."

However, Lange tells House Beautiful that she sees the work she's had done to the house as more of a restoration than a renovation. "We tried really hard to be very, very respectful of the fact that it is an over 100-year-old house, and we weren't trying to make it look like a new house," Lange says. While she did complete some more invasive projects—like transforming the attic into an easily accessible, fully equipped guest floor and lifting the entire house to add a modern basement with a gym, laundry room, and wine cave—she made sure to do so while honoring the history of the home and keeping the updates as authentic as possible without sacrificing livability for her family.

Lange saved as many original details she could before diving into the project, like moldings, doors, and windows. Whatever her contractors couldn't restore, they replaced with similar of-the-time pieces so the house looks as close as possible to the way it did in its heyday, which as Lange describes it is when the Beales first bought the property. Rather than replace the windows with new glass, they put in restoration glass: "It's single pane and it's slightly wavy. It's what they would've used in the early 1900s," Lange says.

Because the house has been so well documented over the years, the team was thankfully able to replicate the architecture so the home would look as authentic as possible. For example, Lange felt the columns on the front porch didn't look quite proportional after a previous renovation, so she had them redesigned to be more historically accurate to the early 1900s. The same with the iconic diamond-lattice windows that decorate the house: They were a bit larger when Lange bought the property than they would've been at the turn of the century, so she "changed all of that back to the original and re-added upstairs terraces off the back of the house where they had existed" but had been removed.

Every change made to the home was done so out of respect for its history. Even the renovations done to make the space more livable for her family highlight the original beauty of the house and the natural beauty of the gardens. For example, Lange added French doors throughout the main floor where there had been solid walls—for easy movement, yes, but also so she could catch glimpses of the gardens from almost every room.

"Maybe it isn't the way it was originally, but it isn't out of keeping with houses from that time period," Lange says. "I love every inch of the house. It's really labor of love."

As for the future, Lange can't imagine renovating any other parts of the home, but the idea of redecorating isn't off the table. "I'm always in the mood for something new," she says. "The living room right now has a lot of different fabrics, a lot of brown and white and pale blues. Sometimes I'm like, 'Maybe I want an entirely white living room, just very different.' More Michael Taylor, California 1970s—I don't know." For now, Lange is content with being able to enjoy her home, its gardens, and the vibrant history that comes with it.

Curious to hear more about Grey Gardens? Listen to this episode of our haunted house podcast series, Dark House, for exclusive ghost stories and insights into the home's compelling history.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram and TikTok.

You Might Also Like