You Can Now Buy a Grateful Dead Bong, and Life Is Complete

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

On the evening of December 30, 1978, the Grateful Dead were hanging out backstage as the clock ticked down to their 7:30 show time. The venue was UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion, and Bill Walton—the former Bruins hoops star and towering red-headed Deadhead who’d led the team to two national championships only a few years before—had used his considerable sway to convince the school’s brass to let Jerry and the gang camp out in the home team’s luxurious locker room.

What happened next is the stuff of Dead lore: The band’s sizeable, don’t-leave-home-without-it tank of nitrous oxide had frozen so, naturally, the crew rolled it into the showers to be warmed up. This worked, and it wasn’t long before the scene devolved into a steamy, nitrous-soaked shower party with lots of students first getting very high and then getting very naked. For the Dead, this would have been just another a day at the office … but suddenly the door swung open and—oh, shit—in walked the aforementioned Bruins brass. Understandably, they were pissed.

As it happens, I was nearby while the naked nitrous shower shenanigans were unfolding, standing some 300 yards away, just outside the arena, between two large, poorly groomed shrubs. I was 13, but a nervous 13, and my two friends—Barnaby, who I’d known since I was two, and a kid I’ll call Walter—had determined that this was the safest place to get high before the show. None of us had smoked a lot of dope at that point in our lives, and we certainly hadn’t smoked much in public, but Walter had pinched a few fingerfulls of one-hit Thai Stick from his record-executive father, so here we were, deep in the shrubbery, trying to stifle our new-smoker coughs.

Of the many, many Dead shows I would go on to see, this was the first. But it wasn’t my first time in Pauley Pavilion. In fact, I’d been going there for years, mostly as a little kid and exclusively in the company of my father, a gentle Bruins fan who brought me to countless games, patiently explained the sport, shared hotdogs and peanuts in the seat beside me, rested his big arm across my shoulders. Until the night I went with two friends and a small bag of weed to see the Dead, Pauley Pavilion had been, for me, a place a boy would go to be with his dad.

The show itself? Yeah, I honestly don’t remember much about it. I don’t remember them playing “Shakedown Street” (for only the third time ever in California), nor do I remember the rest of the second set which featured “Bertha,” “Scarlet>Fire,” and “St. Stephen.” I don’t recall them slipping into “Ollin Arageed,” a souvenir tune notably played at the band’s recent gigs at the foot of the Egyptian pyramids, which they would perform a grand total of nine times. But I do remember this: I remember the whirling dervish dancers spinning themselves silly in the hallways, never so much as glancing toward the stage; the tapers section that, once the Thai Stick bit us, looked like a field of hungry silver insects; the ponytailed guys sashaying down the corridors mouthing “Doses … Doses … Doses.”

I also remember the rough and early edges of a feeling—one I couldn’t put words to at the time—that would grow more defined with every Dead show I saw. Most clearly of all, I remember lying in the middle of UCLA’s baseball field after the show, with Barnaby and Walter, the three of us still high as jaybirds, our skinny backs pressed against the manicured grass, staring up at the sky, wondering if maybe we’d just glimpsed adulthood.

This was, of course, years before I started to think about what I wanted to do with my life, or even what it meant to have a life. All I knew, sitting out there in center field, was that the entire experience had felt welcoming and wonderfully right in a way that nothing before had. Today, having gone grey, having careered, having blown through a good portion of my allotted years on this earth, having seen how full of love and yet how fragile our days can be, it’s strange to look back on a single night that transpired close to half a century ago and realize that, in that moment, a fuse had been lit—and that I had been clueless as to how important the moment would become. It would nudge the direction of everything that followed, swallowing my time and money, god yes, but also supplying the soundtrack to moments high and low across the decades, shaping values and friendships, even playing into the way I defined myself to myself.

I mean, how could I have known then that Barnaby, the goofball giggling next to me, and I would not only remain friends for the next 45 years (and counting) but would one day collaborate on a book with Keith Richards? That I’d meet a girl, fall in love, and leap into marriage, that we’d have a couple of unstoppably great kids, that our relationship would fall painfully apart, that we’d spiral into divorce? How could I have known that I’d fall in love again, that I’d marry again, and that I’d have the heartbreaking privilege of watching my father—my father who’d cheered next to me as Walton and the Bruins vanquished all comers—now quiet in his hospital bed, slip softly and forever out of consciousness?

I never went “on tour.” Or sold kind veggie burritos in the parking lot. Or brought bongos to the drum circle. Nor did I ever prance around the arena perimeter, 800 miles from home, holding one finger-in-the-air along with a cardboard sign reading, “Do YOU have my miracle ticket?” Still, I caught more than my fair share of shows, mostly with a tight group of friends who were as game to squeeze into massive stadiums (like the Carrier Dome, with room for 40,000 Heads) as they were to hit small clubs (for Weir). There were tough moments (like at the Long Beach show in ’81 when the guy in the Hawaiian shirt who looked like an undercover cop turned out to be an undercover cop; like at Ventura two years later when a leathered-up Hells Angel stole the photos I’d taken and printed of Jerry at a JGB show) and mind-blowing moments, like one particular New Years show at the Oakland Coliseum Arena when, tripping on Gooney Bird blotter, I realized the person sitting on my right (the woman who would become my ex-wife) and the person sitting on my left (Barnaby) were born on the same day, in the same year, in the same city 2,900 miles away. And in the same hospital. We couldn’t begin to calculate the odds. But during “Drums” we sure tried.

And then there was the show from which I’m not sure I completely returned. In July of ’84, the Dead played the Ventura Country Fairgrounds, an outdoor venue normally home to horse races and swap meets that Garcia reportedly loved because it was so close to the beach he could see the waves from the stage. I was there with Barnaby, and we’d each eaten a hit of purple gel purchased from a guy named Shark, who was so high his eyes kept crossing during the transaction. We came on during “Loser” in the first set and then held on, barely, for the rest. But when the opening notes of “Morning Dew” groaned unexpectedly out of “Space,” creaking like a wooden ship at sea, I noticed the clouds above us beginning to swell with color and meaning. And I understood that the band was now controlling the weather. I looked at Barnaby. We didn’t need words; he saw it too.

Together we stared at the gathering clouds; the crowd around us felt the change, as well. We looked toward the bleachers and the mass of colorful tie-dyes swayed in acknowledgment. Everyone saw what was happening. It was obvious. In that moment, I felt, on a molecular level, that I was part of something larger than myself. Not just one of the 15,000 Heads dancing in the fairground dust, but part of a continuum tracing back to the band’s very first performance at Magoo’s Pizza Parlor, in Menlo Park, on May 5, 1965. That wonderfully right feeling I’d first sensed at Pauley Pavilion? If I had to pinpoint the moment when the feeling came into its own, when its edges grew defined, when I could begin to put words to it, it was during that “Dew.” The music was powerful and profound, but I instantly realized that the music wasn’t the point. The point was Barnaby. The point was the people in the bleachers and the people who’d pilgrimaged from points unknown to be a part of this ritual and the numberless rest who’d been along for the ride since Day One.

There’s always a moment of electric bonding when, decades after the fact, two people realize they were at the same show. This happened recently when I was speaking with Mark Pinkus, the affable president of Rhino Records who’s also in charge of the entire US catalog for the Warner Music Group as well as Grateful Dead Properties. “July 13, 1984,” he told me within three minutes of meeting him. “At the Greek. That was my first show. The encore was ‘Dark Star.’ I saw 73 shows and I never got another one.” I’d been there, too, and it turns out that, nearly 40 years later, we’d also both seen the same Boulder shows this summer.

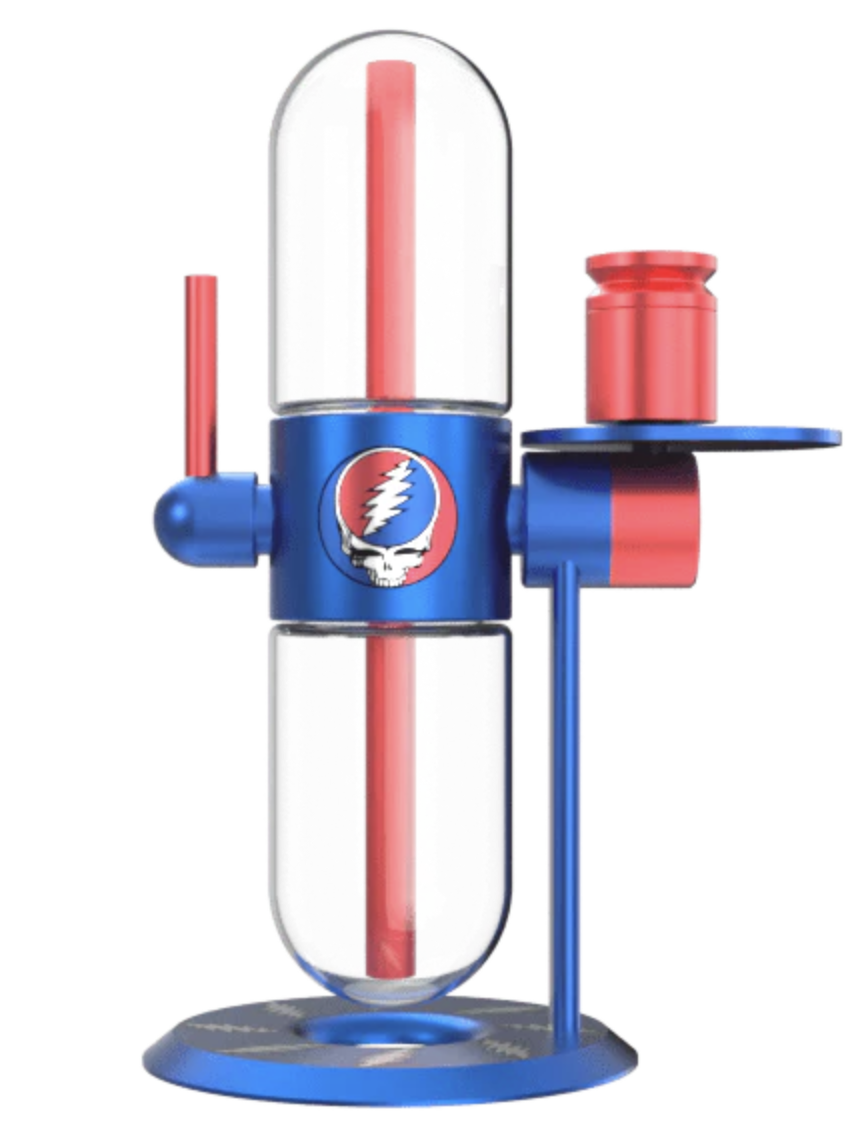

I was talking to Pinkus because he oversees, among many other things, the Dead’s brand extensions and there’s a new extension dropping in November that I found intriguing. The Dead have popped their logo on a wide range of products over the years; on their site, Dead.net, a Head can find everything from dancing bear PJs to a branded “Igloo Steal Your Face Playmate Pal 7 Qt. Cooler” to tarot cards to a “cosmic mushroom foraging tool.” But the newest brand extension was unique and a first of its kind: a bong. Or, as Pinkus refers to it, “a cannabis accessory.”

Allow me to press pause for a quick sec to consider that, until now, the Grateful Dead, born of Acid Tests, raised in the Haight, and perhaps more associated with drug use than any other band, had not yet launched a branded “cannabis accessory.” The Dead, it turns out, had taken this endeavor quite seriously, noodling the decision for years—“We want to make sure that the brands we partner with are the right partner for the Dead,” Pinkus told me, “and the band ultimately approved it”—and in the end chose to slide their Stealie on arguably one of the finest bongs on the market, the Stündenglass, a beautiful, space-age, highly effective gravity bong. It’s a bong I know well.

GRATEFUL DEAD X STÜNDENGLASS GRAVITY INFUSER

Studenglass

$599.00

“A gravity infuser is what we call it,” Chris Folkerts, CEO and founder of Grenco Science, the company that makes the Stündenglass, told me. (It might theoretically be possible to improve on the word bong, but gravity infuser is not in the top 50.) There will also be a branded G Pen vape. Folkerts, who in the past has partnered on paraphernalia with Snoop and Wiz Khalifa, told me that working with the Dead feels special to him. At his first show, a post-Jerry late ’90s gig in St. Louis, he remembers, “I had a pretty profound experience on LSD. And I think that it was one of those things that forever changed my life.” Folkerts, who told me that he was “negative 27 when the band started,” looks at the Dead scene as a “living, breathing organism” that “decades later, continuously grows, and you still feel like you’re part of it.” Honestly, staring at John Mayer’s tortured, 40-foot O-faces writhing across the Jumbotron at Folsom Field last July was challenging for me, but when I looked away, yeah, I still felt like part of the scene.

Aside from learning to avert my eyes every now and then, I’ve gained a few insights during my years in and around the Dead: I learned that every silver lining has a touch of grey, that there’s nothing you can hold for very long, that once in a while you get shown the light, etc., etc. But also to appreciate uncertainty, to give yourself over to the moment, to recognize that the smallest things that happen on stage can be the most meaningful, to understand why a middle-aged fat man raising his arm ever so slightly can elicit a roar from 50,000 people.

And early on I learned something else, something that Garcia once articulated: “To get really high is to forget yourself and to forget yourself is to see everything else.” (He went on to talk about becoming an “understanding molecule in evolution,” which we’ll leave for another day.) That sentiment—and the quest for the wondrous if temporary abandonment of the self—has always been at the core of my experience with the band. Likewise, while the music was important, so was the stranger standing next to you. As was the waiting in line for tickets (where, in 1987, I met Peter, who became another lifelong friend), as was the cramming of everyone into the car (including Brian, at 6’5”), the long drive, the road food, the misadventures along the way, the fevered anticipation that descended in the minutes just before the show. It was all about the pilgrimage. And the people. To this day, what makes the Dead something I think about—and think back on—so often are those shared experiences.

That sharing, of course, was part of the Grateful Dead’s original DNA, from the tape-trading (a construct unique to the Dead) to the set breaks (seemingly engineered for socializing and the communal consumption of joints and juicy orange segments) to strolls down Shakedown Street (another construct unique to the Dead), to, once safely home, the passing ’round of a bong while reliving the show’s high points. The Grateful Dead created shareware before there was shareware.

As it turns out, the Dead and Pauley Pavilion are linked together by more than Bill Walton and yours truly: They both opened for business in the spring of 1965. But just two years after the Dead had their locker-room nitrous blowout and I’d seen my first show, the arena suffered some damage and the holy hardwood, once home to the feet of Walton, Wooden, and Kareem, had to be replaced. My father, who’d gone to UCLA and remained a proud Bruins fan until the end of his days, purchased a tiny chunk of that original court. It came encased in clear acrylic, just 3 inches by an inch and a half, with the words “Original Pauley Pavilion Floor 1965-1980” etched on the surface. It was a small piece of basketball history, to be sure, but also a reminder of the history he and I shared, sitting side by side, all those years ago, a father and his boy eating hot dogs and cheering on the home team.

Of course, that small sliver of flooring held a piece of my own history, too, one that my dad couldn’t have understood. When I went to his apartment for the last time, the day after his funeral, I noticed it on his desk. I picked it up and held it for a second. Then I slid it into my pocket. Today, it sits on a shelf in my office; there’s an open space next to it with just enough room for a new bong.

You Might Also Like