What Not to Say to Someone Who Lost Their Partner

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

When the body ends, so does time. I learned this one sweltering day in August three and a half years ago when my sweet man, my constant friend, my beloved husband collapsed less than a kilometer from the finish line of a half-marathon he would not complete. His heart suddenly stopped for no known reason. He was running and then he was not. He was gone.

Kurtis had vivid brown eyes and quick, slender fingers—a mane of gorgeous hair. He practiced card tricks in our cramped bathroom, tricks he performed for me later while singing his own background music with gusto.

The day Kurtis died, I officially identified him at the hospital, spelled his name for the doctor: Kurtis with a K. After, I went to sit in the small hospital’s waiting room. Numb and dazed, I was in clinical shock, though I did not know this. I was 31; Kurtis was 32. A year and a half before, we’d spoken our wedding vows to each other while holding hands beside a perfectly blue ocean.

When I arrived at the waiting room, a social worker greeted me. Her name was Amy—which is my name—and this upset me. I saw the soft gleam of her wedding band. I sent her away quickly, this Amy whose partner was still alive. Once she left, I sat in a chair. The waiting room was a nice enclave. Windowed on three sides, a view of four leafy trees swaying at the base of a slope of perfectly cut grass. The hill rose until its soft curve met the level skyline, but what was beyond, I could not see.

That day, I entered a grief so vast, so painful that I did not know how to continue to exist. It was also the day I became someone that other people did not know how to exist around. They worried about what to say.

The worry comes from a well-intentioned place: Most of us do not want others to suffer, especially if they are right in front of us. Yet this instinct—while human and good—is flawed because it often prompts people to try and help grievers “feel better,” which is an impossible task.

Below are some common things I heard from people after Kurtis died. All were painful for me to hear, though I know people meant well. I share these words gently because I believe if we can all understand each other more clearly, then we will all hold each other that much more closely.

1. “I can’t imagine what you’re going through.”

Meant most often as a reflection of the enormity of grief, this statement stings every time. We can imagine anything. If someone cannot, they have chosen not to. This is a choice usually rooted in understandable fears of death and pain. I wish that we might replace “I can’t imagine” with “I can only imagine,” as the latter offers a willingness to join the griever in their agony as well as an honesty that admits: Your pain has not yet happened to me.

2. “You’re so strong.”

I hear this a lot, and I know it is intended as a compliment. Yet, when we tell grievers they are strong, we do not allow them any space to be as they are: exhausted, devastated, afraid. When we praise and admire strength in grievers, we tell them, however inadvertently, that all we value is strength. This is so isolating because it places people who are grieving in a position of trying to show a facade of strength. But they are struggling. They do not feel strong. They are desperate for help, for tenderness, for a place where they can be as they are.

3. “I’m here for you when you are ready.”

Ready for what? I always wonder this. The implication of this particular offering seems to be that the griever must go to the other person when they are ready for living again. I believe when people say this they mean to respect grievers’ pain, but they unintentionally end up leaving them alone with their grief. Instead, let us meet them in the current moment: “I am here for you now.”

4. “You just need to go back to work.”

People tend to think the structure of paid employment will distract from and therefore ease the formless pain of grief. Buried in this statement is the assumption that without paid labor, we are not distracted enough, our time is too open to sadness. This assumption also ignores a fundamental truth: Grief is work. Physiologically, the brain is trying to adapt to a new and painful reality. This relentless physical and emotional labor prompted by death is not paid labor, but it is still very much work.

5. “Since my divorce, I know exactly how you feel.”

The instinct to relate to one another is a kind one. Yet, being divorced and being widowed—both terrible rifts in time and relationship—are different kinds of rifts, each deeply painful in its own way. To conflate one with the other robs each experience of its own identity, its own pain, its own effects on the self. Each deserves its own space and understanding.

6. “You’ll get married again.”

As a very young widow, I hear this a lot. I know people are trying to comfort me, but the reality is that no one can guarantee marriage. This fact renders the statement hollow. Also, telling someone grieving the death of their beloved that there will be another beloved one day seeks to replace one with the other as a cure for pain. This is impossible: The ache of loss never goes away, and a loved one cannot be replaced. Even if another marriage is hoped for, any new relationship will always live alongside grief.

What to offer instead

A few summers ago, at a cocktail party, a poet and I exchanged pains. When the poet asked how long it had been since Kurtis’s death, I told her two years.

“So soon,” the poet said.

My eyes filled with tears born from the relief of being seen. No one had reflected this truth to me before. One, five, 10 years—it never matters. Grief is always soon.

When we are quick to try to ease the pain of loss, we mean well, but we ignore the fact that while grief may change shape and form, it is not going away. Of course, there is no perfect way to support grievers—each person’s experience is as unique as they are—but instead of trying to make those who have lost “feel better,” I urge people to try and make them feel seen: “You must be in a lot of pain.” “You must be so tired.” “You must feel awful.” This names the relentless realities of grief while also allowing grievers to share their suffering, an act that reminds them they are not alone.

By offering space for the agonies of loss, we not only carry grievers more tenderly but we also recognize that grief is the final form of love. By grieving with others, by witnessing each other’s pain, we help bear what we all must: the beautiful weight of love at the end.

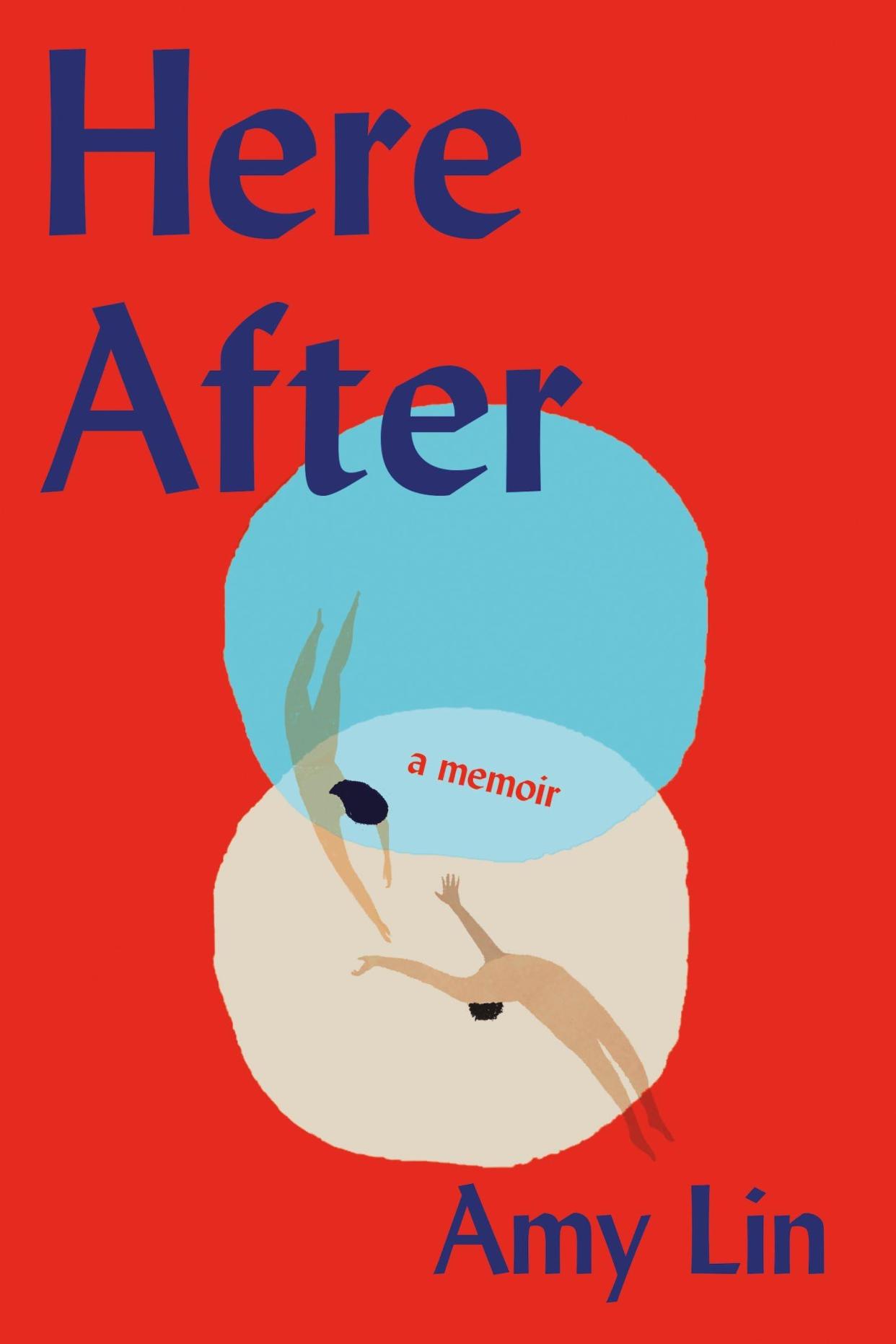

Here After: A Memoir, by Amy Lin, is published by Zibby Books.

Here After: A Memoir

amazon.com

$17.64

Zibby BooksYou Might Also Like