Not the Alamo: Fields near San Antonio yield evidence of deadliest battle in Texas history

SAN ANTONIO — It was the bloodiest armed conflict in Texas history.

On Aug. 18, 1813, some 1,400 people died at the Battle of Medina and during the merciless streak of executions that followed.

Yet the incident left behind barely a physical trace among the wooded fields near the confluence of the Medina and San Antonio Rivers. And it hardly made it into many modern Texas history books until recently.

On the old road to Laredo south of San Antonio, the battle pitched Spanish royalist forces against Mexican republicans, many of them Tejanos, joined by some Anglo-American and Native-American allies.

More than 20 years before the Texas Revolution (1835-1836), it could be seen as one of the earliest major tangles between the central powers in Mexico City and breakaway forces in what became Texas.

More: Nueces River surprises two river tracers

On that day, the royalist army under Gen. Joaquín de Arredondo fought the republican forces of the Gutiérrez-Magee expedition serving under Gen. José Álvarez de Toledo y Dubois.

Arredondo's men mowed down revolutionaries then treated the survivors with brutality. The royalists also chased down sympathizers, punished family members, and left the bodies of slain combatants unburied in the field

A young officer named Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was among the triumphant troops and presumably learned from the experience.

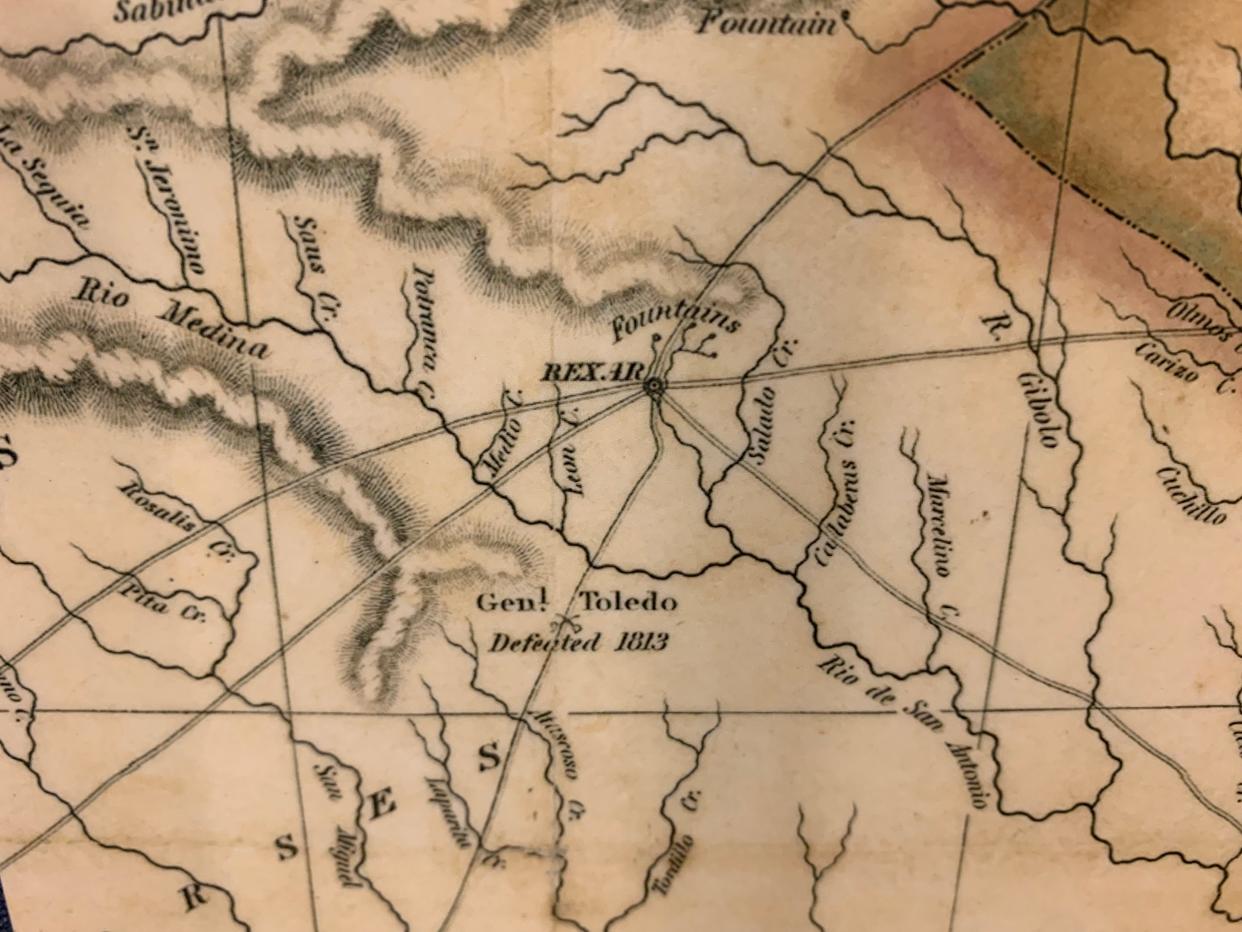

For more than two centuries, historians have debated the exact site of the battle. A map put together by Stephen F. Austin in the 1820s showed the approximate location.

During the past three digging "seasons," however, archaeologists associated with a veterans' group have unearthed bits and pieces of durable evidence on private land south of San Antonio.

They don't pinpoint the actual battlefield, still a matter of contention, but the musket balls and other artifacts strongly indicate the general location of a running battle.

Some of that evidence is on display at the Witte Museum — at least through the end of the year, perhaps longer — in this city of marvelous museums. Historians can start to set the record straight.

"Three state historical markers are incorrect," says Bruce Shackelford, curator of Texas history at the museum. "What they say is correct, but they are not in the right locations."

How did the Battle of Medina get so bloody?

As part of an on-and-off Mexican revolt from Spain that started in 1810, Tejanos declared an independent republic in northern Mexico, in part because they were being taxed by distant imperial and provincial capitals.

"Taxation without representation," Shackelford says. "San Antonians were furious."

Spain treated the armed resistance as an act of revolution against its empire, and acted as imperial powers often do.

More: Want to visit San Antonio? Readers rave about city while sharing tips on sites, food, fun

Curious about this half-forgotten chapter of Texas history, I visited the vicinity of the Battle of Medina a few years ago while tracing 50 Texas rivers from their sources to their mouths, or vice versa.

The land around it is hard to love.

While the Medina tumbles gorgeously from the southern rim of the Edwards Plateau to the towns of scenic towns of Bandera and Castroville, once it takes a left toward the San Antonio River, it looks more and more forlorn. Aside from the Medina River State Natural area and a few tidy suburbs, it is mostly scrubby ranch land now occupied by industrial and mining projects.

"The main site for the battle was probably destroyed by sand excavation," Shackelford says. "But we do have Arredondo's description, which was translated and published by the Texas State Historical Association in the 1930s."

Since the current archaeological dig is on private land, skip a trip to the area.

What you can see at the Witte Museum

"The royalist troops scavenged the fields after the battle," Shackelford says. "They left the bodies. And they kept a detailed inventory of what they collected."

Although the Witte exhibit displays only a few items actually recovered from the dig, it provides excellent historical context as well as artifacts closely associated with the time and place of the battle.

For instance, a charismatically displayed English musket from the period is not from the Battle of Medina, but "it is exactly the type listed on Arredondo's inventory," Shackelford says. "The Spaniards recorded everything, including money making. They controlled a sixth of the silver on the Earth. And everything was taxed."

That explains the dark green Spanish army officer’s coat, associated with tax collectors, on display.

More: Meet me in San Austin: It's time to explore the idea of an Austin-San Antonio 'mega-metro'

The musket balls and other small items likely from the battle were dug up by the American Veterans Archaeological Recovery team. Among the other finds were an iron plate and the remains from the process for creating projectiles.

"We left out of the exhibit the square-cut nails that they found," Shackelford says, "because they can't be dated yet. That kind of nail was still used much later."

"The team has since found more munitions on the site," says Michelle Everidge, chief of strategic initiatives and historian for the Witte. "We might add them to the exhibit later."

'That's how they maintained their empire'

Meanwhile, don't skip the rest of the Witte, which includes fantastic displays of indigenous animals, exhibits on geological time and plenty more Texas history. Outside, stroll around the old structures, gardens and walkways set along the San Antonio River near its headwaters.

The exhibit itself will stay with you. While the run-up to the Battle of Medina involved almost 100 years of frustration on the part of colonists, soldiers and clerics posted in San Antonio, far from power and wealth in New Spain, the aftermath also lasted for decades.

"Consider the people they executed, the folks they chased to Louisiana, the women and children they locked up," Shackelford says. "They gave no quarter, which was their strategy since the Moorish occupation of Spain."

Everidge: "That's how they maintained their empire."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: What happened at the Battle of Medina? Texans are finding out