Take a nostalgic trip inside the Orange Bowl — ’72 Dolphins’ perfectly imperfect home

It was rickety. It had virtually no parking. The seats were uncomfortable. The bathrooms were filthy.

But for the fans who packed the stands and waved white hankies during the Miami Dolphins’ undefeated 1972 season, the Orange Bowl stadium was perfectly imperfect.

It was our rickety home, a raucous cauldron of 80,000 fans and one of the most intimidating places to play in the NFL. Miami went on a 31-game home unbeaten streak from 1971 to 1975, adding to the OB’s mystique.

The stadium was built at 1501 NW 3rd St. in 1937 as a Depression Era Workers Progress Administration project. It originally had 23,000 seats, cost $325,000 to construct and was named Roddy Burdine Municipal Stadium, after department store founder. It was renamed the Orange Bowl in 1959.

West end zone seats were added in the 1940s, a second deck in the 1950s, and in early 1972, Dolphins owner Joe Robbie invested in renovations, including 5,000 bleacher seats in the east end zone.

The Orange Bowl was torn down in 2008, but the memories live on like a timeless scrapbook.

WHITE HANKIES AND 55 CENT ZUM ZUM HOT DOGS

Jose Sotolongo, executive director of the Miami-Dade Sports Commission, was an 11-year-old at Shenandoah Elementary when his father bought a pair of season tickets for $120 to see the 1972 Miami Dolphins at the Orange Bowl. Section B, Row 49, Seats 10 and 11.

Young Jose was obsessed with the Dolphins. His bedroom was covered with Dolphins posters. He owned an LP record by Bob Griese titled “How to Quarterback” and another by Paul Warfield called “How to Catch a Pass.”

He recalls every Orange Bowl visit that season in vivid detail.

“We’d park on Southwest First Street and 16th Ave, walk to the stadium, and you knew as you walked through those crowds of people in orange and aqua that something special was happening,” Sotolongo said. “A company called Zum Zum was the stadium vendor. Hot dogs were 55 cents, Coke 45 cents. I also remember some fans bringing flasks of alcohol inside hollowed-out Bibles.”

Like the other 80,000 fans in the stadium, Sotolongo had a white hanky to wave at exciting moments. “It was electric seeing all those white hankies,” he said. “I’m almost 61 now, and I can picture it like it was yesterday.”

Unlike stadiums today, the Orange Bowl offered nearly identical experiences for wealthy fans and blue-collar fans. Other than eight rows of chairback seats up front, there was no difference.

“No matter if you rolled up in a ’65 Corvair or a limo, you were going to eat the same hot dogs and sit in the same uncomfortable fiberglass seats that were hot as hell. There were no suites. Sports were more wholesome back then.”

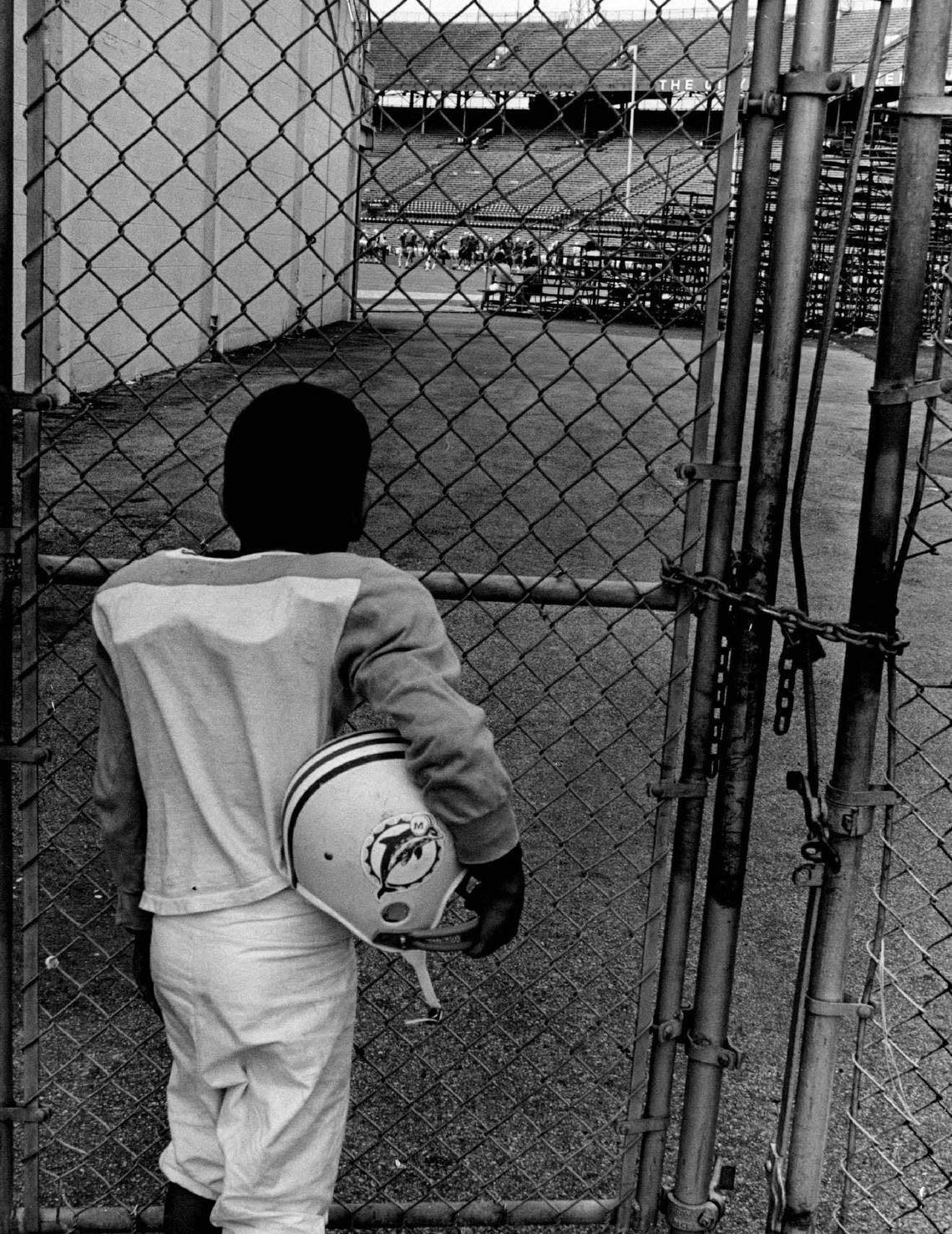

How wholesome? So wholesome that the Orange Bowl gates remained open every Saturday morning for the Dolphins’ walk-through practices. Coach Don Shula didn’t mind when neighborhood kids showed up to watch.

Miami Herald writer Santos Perez was one of those kids.

“I lived three blocks away, me and my friends would go over on Saturdays and the Dolphins players would play catch with us after practice,” Perez said. “Marlin Briscoe and Tim Foley were really nice. Can you imagine kids today just walking into a stadium to play catch with NFL players?”

‘HEART OF THE NEIGHBORHOOD’

Cookie Garcia spent a chunk of her life living in the shadow of the Orange Bowl.

Her family moved into a house that sat about two blocks west of the stadium in 1948 just months after she was born. Garcia was 24 years old for most of the Dolphins’ undefeated 1972 season.

Old enough to help park cars at her family’s home before games.

“We had regular parkers,” Garcia recalled. “I actually had regular parkers before the Dolphins even existed from UM. They stayed after the Dolphins showed up. I had like 10-14 parkers at our house. They came to every game, and it was just a fabulous time for the Orange Bowl.”

Garcia had room for 10 cars in the backyard, four cars in the front yard and promised her customers they would not be blocked in. She doesn’t remember charging more than $10, even for the big games.

“To be honest with you, we never went more than $10,” Garcia said. “Some of our parkers would go, ‘No, that’s stupid’ and they’d give you a $20. I would go, ‘No, $10 is enough.’ And they’d go, ‘No, you keep it.’ So occasionally we would get $20. But on the norm, we only charged $10.”

Some of Garcia’s regular parkers would come three hours before kickoff to tailgate, barbecuing on her family’s concrete table.

“It was just really wonderful,” Garcia said. “What was really neat is even though they didn’t televise some of the games, we could sit on our front porch and hear the games. That was really neat.”

And when the wind blew in from the east, Garcia could hear the Orange Bowl crowd and public address announcer “extremely well.”

“The Orange Bowl was sort of the heart of the neighborhood,” Garcia said.

‘THE ENTIRE STADIUM SHOOK’

Michael Brooks was a 14-year-old just looking to spend time with his father and brother. He witnessed the NFL’s lone perfect season in the process, from the upper deck of the Orange Bowl as a season ticket holder.

Those memories have stuck with him, even the ones he would like to forget.

Like the Orange Bowl parking nightmare. With little to no parking at the stadium, most fans were forced to park their cars at houses in the surrounding Little Havana neighborhood.

“The parking was horrible,” Brooks said with a laugh. “They gave you the $5, no block special. But you always got blocked. Sometimes the people that sold you the spot didn’t even live there.”

Then there were the Orange Bowl bathrooms.

“The bathrooms were disgusting,” Brooks recalled. “Literally when you went to the bathroom, you couldn’t walk your normal stride because there was pee all over the floor.”

And the bleacher benches were memorable for the wrong reasons.

“The seats at the Orange Bowl were the most uncomfortable,” Brooks said. “They stuck to your legs, and you were itching for forever.”

But the Orange Bowl experience was one Brooks would like to relive.

“It was so loud,” Brooks said. “The crowd was right on top of the field. In the Orange Bowl when it got loud, the entire stadium shook. You knew the place was a dump, but I loved that place so much.”

Bruce Rubin, another diehard Dolphins fan, can relate. He was 25 during the Perfect Season.

“The atmosphere on Friday nights for UM games and Sunday afternoons for Dolphins was completely different. Hurricane games were colorful. There were bands, lots of cheerleaders, university students, and the Band of the Hour at halftime. Dolphin games somehow seemed more serious to us.

“Well into the season the atmosphere was like the closing innings of a no-hitter. Could we win yet another game? Was going undefeated even possible? I remember my dad telling me, after the perfect season, to always remember what we saw together. I do.”

LOCKER ROOM ‘WAS A LITTLE FRIGHTENING’

Being a son of the Dolphins owner in 1972 had its challenges. For example, fans blamed your father for getting rid of “Flipper”, the TV star dolphin that frolicked in a tank in the Orange Bowl’s East end zone during the team’s early years.

(For the record, says Tim Robbie, son of then-owner Joe Robbie, the Flipper fun ended because the Seaquarium, from which he came, decided it was too stressful to transport him back and forth.)

But being Tim Robbie also had its perks. What other senior at Miami Archbishop Curley High could say he charted plays on the Dolphins’ sidelines for assistant coaches Howard Schnellenberger and Monte Clark?

“Dolphin Mania was in full swing, the Orange Bowl was always filled to the brim, it was very raucous and intimidating for opposing teams,” Robbie said. “I remember being in the Dolphins locker room at halftime and if something had happened at the end of the first half to get everybody excited, you could feel the rumbling of the seats above you. It was a little frightening.”

Robbie’s fondest memories are of the sea of white hankies, the brainchild of longtime announcer Rick Weaver.

“Any time you jumped out of your seat for something exciting, you had a white hankie in your hand and you were waving it,” Robbie said. “The Steelers’ Terrible Towels were born from the Dolphins’ white hankies. And everyone had them, no matter how rich or poor. There were no VIP fans, everyone was on the same footing when you went to the Orange Bowl.”

‘A PLACE FROM HELL’

For Jeffrey Raskin, the winning is what made the Orange Bowl special.

“When you went to a game in the Orange Bowl, you let the parking and the amenities disappear from your brain because the games were so exciting and they were winning,” Raskin said. “Having poor concessions, poor restrooms, bad parking, difficulty getting in, that didn’t become an issue. You didn’t even worry about that because you were so excited to go to the games.”

Raskin was 32 years old during the Dolphins’ historic 1972 run and attended every game. A season-ticket holder since the inaugural season in 1966, Raskin’s seat was halfway up the lower deck on the north side of the stadium.

“The best thing about the Orange Bowl was how close you were to the field and how much noise you could make,” Raskin said. He remembers the challenging parking situation, the tight aisles that lined the stadium and the flooded bathrooms.

“As far as going to the bathroom, I made sure before I went in there that I didn’t drink a lot of water or Coke all day long so I could maybe get through a game until the very end without having to go,” Raskin said.

Raskin, now 82 years old, also brought his own seat cushion to games to help make the metal bleachers bearable.

“Once you got in the stadium and the place became alive, it just reverberated,” he said. “The stands would actually move with people jumping up and down.

“For opponents, the Orange Bowl became a place from hell. Teams coming in there knew the crowd was going to be on them and that was a tough place to play. Teams didn’t want to come to the Orange Bowl.”

ON THE FIELD

Dolphins players viewed the Orange Bowl as an advantage because fans were closer to the field than in most stadiums. The steamy South Florida weather also helped.

“I think the most unique thing was playing in the hot weather early in the season,” said Dick Anderson, who started every game for the Dolphins during that perfect 1972 season at safety.

Manny Fernandez, who was a Dolphins defensive tackle from 1968-1975, agrees.

“What made it unique? 105 degree temperatures with 90 percent humidity. How’s that? That was always fun,” Fernandez said.

But the fans also helped create a unique atmosphere at the Orange Bowl.

“The fans were just fantastic,” Fernandez said. “We had the greatest fans in football. I don’t know how the other team could even hear the snap count or cadence being called. They used to disrupt the visiting teams. The fans were really it and it seemed like there in the Orange Bowl, they were all a lot closer to the field.”

The Dolphins dominated regular-season opponents by a combined score of 209-80 at the Orange Bowl during their undefeated 1972 season.

“Time marches on and nothing is forever,” Fernandez said of the Orange Bowl being demolished in 2008. “I obviously have a lot of great memories of different games. But those memories are always there.”

‘IT WAS A MAGICAL PLACE’

Long before he was the owner of Books & Books, Mitchell Kaplan was a long-haired, football-loving teenager whose first job was ripping up the Orange Bowl Astro turf in the spring of 1972 as part of the stadium renovation before The Perfect Season.

“It was the most backbreaking work, a union job for $2.99 an hour in the hot sun,” he recalled. “But I felt like part of the stadium, literally on the ground.”

In 1966, the Dolphins’ inaugural season, his family joined the Velda Farms Huddle club, which included $13 season tickets, coupons for Royal Castle, and an invitation to a player meet-and-greet at training camp. Kaplan attended every UM and Dolphins game at the Orange Bowl for decades.

He always parked at the same house on the corner of N.W. 6th St. and 22nd Ave.

“The Orange Bowl was such a big part of my life; and I was terribly disappointed when they tore it down,” he said. “When they Dolphins moved, they were never as good. The whole mojo was lost. I just loved the OB. It was a magical place. It had personality. In some ways, it was alive.”