Nick Buoniconti never stopped fighting. The late Dolphin’s final battle is still going

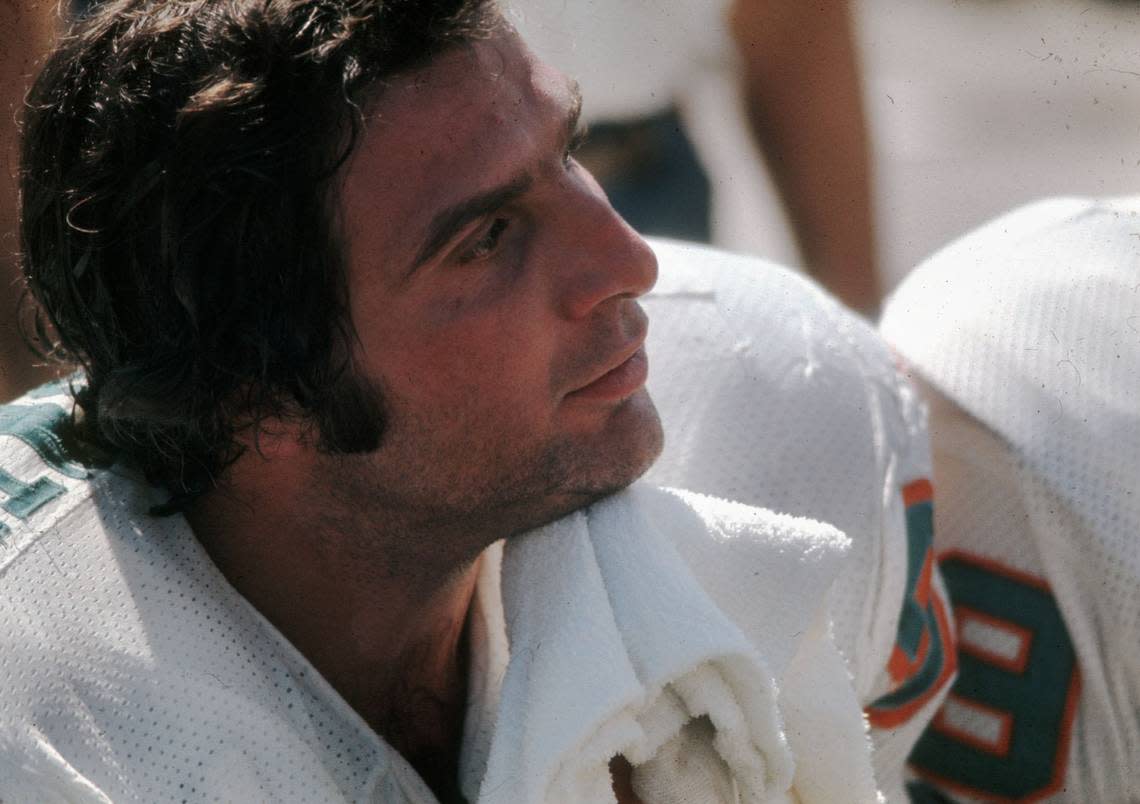

Nick Buoniconti was a fighter. A 5-foot-11, 220-pound linebacker doesn’t make to the Pro Football Hall of Fame without being wired to scrape and claw for every inch of success, without finding a goal everything it takes to accomplish it. This wiring took him from his home in Springfield, Massachusetts, to an All-American career with the Notre Dame Fighting Irish and, eventually, perfection as one of the stars of the 1972 Miami Dolphins season.

The Dolphins’ defense took on the nickname of the “No-Name Defense,” and Buoniconti, undrafted in the NFL because he was a step slow and a few inches too short, embodied everything the group was about during the 1972 NFL season. He played with an edge, and was maybe the only player to ever shout an expletive at Don Shula and have the Hall of Fame coach be OK with it.

Buoniconti fought his way to two Super Bowls, two Pro Bowls, two All-Pro selections and 14 professional seasons, and then he kept fighting. He fought for his fellow players as an agent and lawyer, and fought for his son after he was rendered quadriplegic by a football spinal cord injury in 1985, co-founding the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

Buoniconti, who died in 2019 at 78 after suffering from dementia for much of the final years of his life, is still fighting.

The legendary defender is one of six 1972 Dolphins so far to posthumously be diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopothy (CTE) by the Boston University CTE Center and Brain Bank — All-Pro quarterback Earl Morrall, star running back Jim Kiick, star guard Bob Kuechenberg, All-Pro defensive end Bill Stanfill and All-Pro safety Jake Scott are the others — and no one was a more outspoken advocate for the cause than Buoniconti.

PERFECT MEMORIES

Join us each Wednesday as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the perfect 1972 team

The degenerative brain disease, which at the very least contributed to Buoniconti’s dementia, can only be diagnosed via an autopsy on the brain, and Buoniconti in 2017 took the unusual step of holding a news conference at the Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine to announce he would donate his.

“That was the nature of what Nick did, right? His son was paralyzed and he was looking for a way to help others, so naturally when CTE, or what we suspected was CTE, started happening to him he just said, I was on television for HBO Sports, you have name recognition, you have face recognition,” said Lynn Buoniconti, the wife of the late Hall of Famer. “He was just like, ‘I have to try to make a difference.’”

Nick Buoniconti’s final mission

The reasons Buoniconti wanted to send his brain to the Boston University CTE Center mirrored so many of his teammates’.

There was frustration with the NFL concussion settlement, which netted him just $47,000 and most of his teammates nothing, and a hope the more research done would stop the league’s denial. There was, of course, a faith doctors will one day be able to diagnose CTE in the living and find a way to treat or even reverse the effects of this awful disease. For the players on this high-profile team, there was especially a hope they could serve as an example for others, encouraging more and more ex-players to donate their brains to science and Buoniconti, who stayed in the spotlight as the host of “Inside the NFL” on HBO into the 2000s, was an especially high-profile case.

In 2017, he made sure everyone knew what was happening to him. By then, he already knew Morrall and Stanfill suffered from CTE at the end of their lives — they were both diagnosed by the Boston CTE Center after their deaths earlier in the decade — and Buoniconti was starting to crumble, his symptoms worsening after he first took notice when he was about 70.

He was dead within a decade.

“When he started struggling and he started changing, we discussed it and he was smart enough to say, ‘There is something wrong with me,’” Buoniconti said. “We started looking for answers.”

How Jimmy Johnson won championships — but had to get out of football to get his life back | Opinion

His memory was fading. Sometimes, he would forget how to do something simple, like hang up the phone. He could not remember how to put on a shirt, as was documented in a heartbreaking Sports Illustrated video in 2017. Falls became commonplace, and he became prone to mood swings, angered by little things and depressed more than he let on.

At one point, he started incessantly calling Patriots owner Robert Kraft to lecture him about how he had to do more to protect his players. His wife eventually had to take his phone.

Outwardly, he hid it all well. It’s who he was.

“It was like, ‘Oh, there’s nothing wrong with Nick.’ Well, guess what? There was,” Lynn Buoniconti said. “He was depressed and he was prone to anger, but people made excuses. He’s getting older, he’s getting crankier. He was always tough, he’s getting tougher. No. He was getting vacant. That wasn’t Nick.

“People could say, Oh, he wasn’t that bad, he wasn’t that bad, but they didn’t live with him. ... They didn’t see what happened to someone day after day.”

An incredible life, then decline

Buoniconti was, if nothing else, whip smart. He was an altar boy growing up an an all-around star at Springfield’s Cathedral High School in Massachusetts. When he began his professional career with the team now known as the New England Patriots, Buoniconti balanced a career in the American Football League with schooling to get his Juris Doctor degree at Boston’s Suffolk University Law School. His post-playing career is perhaps even more decorated than his football one.

It made the ending so jarring. For the last two and a half years of his life, Buoniconti needed full-time, 24-hour care, his wife said. He was never in denial about the role football played.

“He had dementia and it was like ALS. He couldn’t feed himself,” Buoniconti said. “Everybody talks about CTE — Oh, you have some headaches. No, no, no. ... CTE is a diving board. If you live long enough, you dive into the pool and in the pool are the four things that the NFL recognizes as things that happen: Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS and dementia.”

The ’72 Dolphins’ 50th anniversary celebration: Five questions with Al Jenkins

When the symptoms started to worsen, Buoniconti knew he had to do something. It wasn’t in him to just fade away. At some point, he and his wife watched Dr. Ann McKee, the director of the CTE Center and Brain Bank, testify before the United States Congress about about the link between football and CTE.

It clarified his next crusade. They called up to Boston to talk to McKee.

“Like everything else,” Buoniconti said, “it became a mission of his.”

A face of CTE

When a doctor’s job is to slice open brains and poke around to figure out what’s wrong, there aren’t many chances to really know your patient.

It was not the case for McKee with Buoniconti.

“Buoniconti is the one I’m the most familiar with because I really got to know him during life and met his wife Lynn, and spent time with them at their house,” she said. “Nick ... has been so outspoken. Even when very clearly suffering very severe symptoms of CTE, he was able to grasp what it had done to him and his concern was for the players who followed him, which was an extraordinary thing for him to have insight into football causing this disease and then the foresight to want no other player to suffer as he had, so that was really, really quite extraordinary.”

Said Buoniconti: “I picked up the phone and called her and she called back, and I said obviously I respect all the work you’re doing. ... I said, ‘We want to bring Nick to Boston, so you see someone who’s in this process, not a brain after the person is gone.’”

More than 90 percent of the brains of former NFL players in the Brain Bank test positive for CTE, McKee said. Multiple studies show every 2.6 years of playing football doubles a person’s risk for CTE.

The next step in CTE treatment and research, McKee said, is figuring out how to diagnose the disease in the living and every brain in the Bank helps.

“He was trying to own it himself, so that other people would realize it’s not embarrassing,” Buoniconti said. “A lot of people would hide or their wives don’t know what to do with someone, and he was just like, I can do this. I want to donate my brain. This is awful. People should not have to go through this.”

The future of football

Buoniconti wold not have played football.

Buoniconti could not imagine he would not have played football.

It’s the eternal contradiction this generation of players had to live through.

Would Buoniconti have ever accomplished all he did without playing in the NFL? Would he still be doing great things now if he never had?

In 2017, he gave conflicting answers to SI about whether he would have played football had he known what it would do to him. This much is clear: He never expected it to affect him the way it did — no one possibly could have back then, in the nascent days of the modern NFL.

His wife now struggles to watch the sport her husband rode to stardom.

“Every time I hear the click of the helmets,” she said, “I know that someone somewhere is going to end up with CTE.”

Buoniconti’s children strictly played flag football up until they were 14, his wife said, and she doesn’t believe there should be any tackling in youth football.

She also has a unique suggestion for how the NFL could better treat a generation of suffering former players.

“They have billions of dollars and they have lots of land, so in actual fact I think every owner should build a facility with 100 beds in it and they should help previous players,” she said, likening it to an NFL version of the Veterans Health Administration. “Instead of going into a home, they should be able to go into [them].”

This conversation with Buoniconti happened to come in October, not long after quarterback Tua Tagovailoa’s scary concussion against the Cincinnati Bengals. As someone who watched a loved one succumb to CTE, Buoniconti was again dismayed.

There’s no doubt the NFL is safer now than it was when Buoniconti played. The sport gets safer almost every year, and the league even changed policies in the middle of this season after Tagovailoa exhibited a fencing response on the field at Paycor Stadium in September, trying to even further reduce the risk of concussed players being on the field.

There’s still a long way to go, though. Buoniconti’s mission is not finished.

“His goal was never to stop the NFL,” Buoniconti said. “His goal was to stop things like what happened.”