Famous daredevil Evel Kneivel’s Idaho stunt nearly killed him. Here’s what happened

Sitting around a table decades ago with a few friends and even more beers, Robert Craig Knievel was at the height of his fame. The stuntman, better known as Evel Knievel, was still reveling in the success of his 1967 Caesars Palace fountains motorcycle jump — and by success, he crashed but walked to jump another day.

A friend pointed to a picture of the Grand Canyon behind Knievel and asked, “Hey, is that going to be your next jump?” Knievel had been performing stunts for over a decade by this point; he was so famous that children played with action figures of him, and thousands of people watched his stunts in person or on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.”

“I’m not sure how many drinks he’d had, but he shot back and said, ‘Yeah, I could jump the Grand Canyon,’ ” Mike Patterson, co-founder of the Evel Knievel Museum in Kansas, said with a chuckle in a recent interview with the Idaho Statesman.

In the end, Knievel never got to jump the Grand Canyon. Then-U.S. Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall denied Knievel permission. So in 1971, he came up with a new location:

Idaho’s Snake River Canyon.

“Over the next couple of years, he found his way to Idaho and the Snake River and leased some land,” Patterson said. “And pretty much said, ‘You know, since I’m the person in charge of this land, they can’t tell me what to do.’ ”

A snake-bitten endeavor

The plan was simple: Knievel would strap himself into a steam-powered rocket, launch himself hundreds of feet into the air with little control over what happened next, travel the approximate half-mile across the canyon, and land on the other side to a cheering crowd.

The reality? A parachute deployment malfunction resulted in Knievel landing about 10 feet away from likely death.

The jump occurred Sept. 8, 1974, just a couple miles east of Twin Falls. Knievel teamed up with rocket engineer Bob Truax to create the Skycycle X-2, a steam-powered, 16-foot-long rocket with a small cockpit around the middle.

“They heated the water up inside the rocket to around 600 degrees,” Patterson said. “And it basically was just pull the plug.”

Knievel was no stranger to crashing — it’s claimed that he suffered 434 broken bones in his career. But the Snake River Canyon jump was doomed from the start.

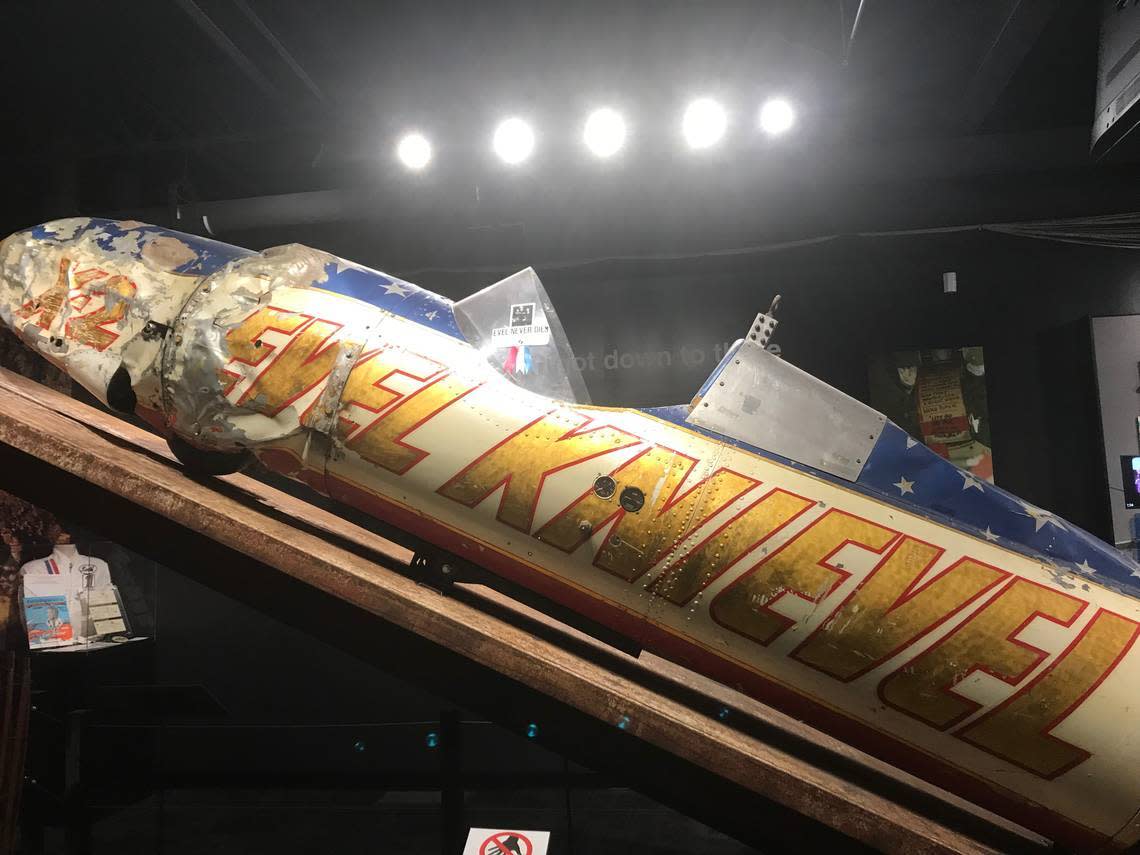

Knievel’s crew initially tested the jump without the stuntman in the rocket a couple of months before the official jump. That rocket plummeted straight into the Snake River and is now housed at the Evel Knievel Museum in Topeka, Kansas. The Knievel family still owns the identical rocket used for the final jump.

Secondly, Knievel’s original suit had D-rings that kept him strapped into the rocket, but his team quickly realized if Knievel fell into the river, he wouldn’t be able to unhook himself. So a new suit was created, allowing for an easier escape. But come the big day, a huge mistake was made.

“One of the crewmen noticed that he put on the original suit, which he was unable to unstrap himself from,” Patterson said. “They told him, and he just said, ‘Too late now.’ He really thought he was in trouble then.”

Then there is the parachute failure. In front of about 30,000 people, Knievel blasted off from his earthen launch ramp and above the canyon at about 300 mph. But as he flew above the gorge, the Skycycle’s emergency parachutes deployed due to the extreme power exerted by the steam-powered propulsion, according to Patterson.

Knievel would’ve made the jump, Patterson said, but instead the steam-powered rocket spiraled toward the canyon floor and rushing river below.

“It disappears below the rim of the canyon, and nobody can see anything,” said Leigh Montville, author of the book “Evel,” on the Discovery Channel documentary “Pure Evel: American Legend.”

Members of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club — who Patterson says were hired to keep the crowd from the canyon’s edge — pushed and strained to see if Knievel had survived.

“He landed about 10 feet from the water by accident,” Patterson said. “Absolutely no control over that. And that’s how close it was for him to pass away from drowning.”

Visiting the jump sight today

Knievel died in Florida in 2007 from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, an incurable lung condition related to diabetes, according to his obituary in the New York Times. But his legend lives on. Fanatics can visit the Evel Knievel Museum in Kansas, which houses hundreds of memorabilia items, including the huge Mack truck called Big Red that Knievel traveled in.

The test rocket resides on the second floor of the museum. Its front is banged and scraped but otherwise remains in good condition, and dirt from the canyon floor surrounds it.

But a little closer to home, Knievel fans can still find the jump ramp about two miles east of the Twin Falls Visitor Center. Visitors can see the ramp from the visitor center, according to Visit Southern Idaho, but a 1.8-mile walk along the Centennial Trail will take viewers to within 100 feet of the iconic site that once hosted one of the most famous stuntmen in history.