‘Where the hell am I?’: Former campers describe harsh introduction to Trails Carolina

The 12-year-old who died last month at a North Carolina wilderness program for troubled adolescents spent his first and only night there on the floor of a bunkhouse. His sleeping bag was inside a small tent with an alarm pinned to the zipper, rigged to go off if he tried to get out, a staff member told authorities.

He had been “loud and irate” when he arrived earlier that day and had refused to eat dinner, the counselor told detectives, adding that the boy had a panic attack just after midnight. The counselor said staff checked on him twice before discovering him unresponsive at 7:45 a.m. with his pants and underwear lying next to his shoulder, search warrants stated.

Little else is known about the boy’s brief time at Trails Carolina in Lake Toxaway, and his cause of death is still under investigation. But interviews with 14 people who attended Trails Carolina between 2013 and 2022 and three former staff members, along with a review of state inspection reports and court filings, reveal that there have long been concerns about how children were treated at the camp.

For many of the former participants who spoke to NBC News, those problems began in their first days with protocols that left them confused and scared. They described strip searches, bathroom restrictions and having to read upsetting letters from their parents aloud.

“I know if I had died on my first night, I would have died believing that I was unloved and unwanted,” said Rebecca Burney, 21, whose parents sent her to Trails Carolina the day after her 14th birthday. “A 12-year-old boy does not deserve any of that.”

Caroline Svarre, whose parents paid to have her transported by two strangers in the middle of the night to Trails Carolina when she was 14, said she was “in shock” her first day.

“I’ve never cried so hard,” said Svarre, who attended the program in 2013. “I cried because I felt betrayed.”

The Transylvania County Sheriff’s Office identified the boy who died only by his initials, CJH, and said the Feb. 3 death was being investigated as possible manslaughter. In a statement, the office said the death “appeared to not be natural but the manner and cause of death is still pending.” Through a representative, the boy’s family declined requests for an interview.

The state’s Department of Health and Human Services has since suspended admissions to the program until April, noting in a letter to the camp’s executive director Feb. 16 that “conditions at Trails Carolina are detrimental to the health or safety of the children in your care.” All 18 children at the camp were removed the same day. The department declined to comment on the conditions at the camp, citing an ongoing investigation.

Trails Carolina, a for-profit program, has said that preliminary information indicates the boy’s death was accidental. In an emailed statement to NBC News earlier this week, Trails Carolina spokesperson Wendy D’Alessandro offered no details about the circumstances, other than to say staff members offer “compassion and patience” to children when they arrive. The camp declined to comment on specific children’s experiences.

The former Trails Carolina participants who spoke to NBC News ranged in age from 12 to 16 when they attended the program. They said that news of a child who had died so early in his stay brought back memories of their own first days at Trails Carolina, which they recalled as full of fear and humiliation.

Each said that their time at the wilderness camp began with a strip search, in some cases with no underwear, by a staff member. One former staff member, who worked at the camp from 2020 until 2022 and requested anonymity because he said he feared retaliation, said searches were conducted if the staff thought a child might have drugs or other contraband. Most children arrived with just the clothing they were wearing, but some said they also brought personal items, such as books and stuffed animals, which were promptly confiscated.

D’Alessandro did not comment on the searches or confiscation, and said the camp follows state regulations to “ensure a safe and dignified intake process for new students.”

After they were searched, the former participants said, staff gave them sets of hiking clothes and took them to cabins or campsites to meet the other children.

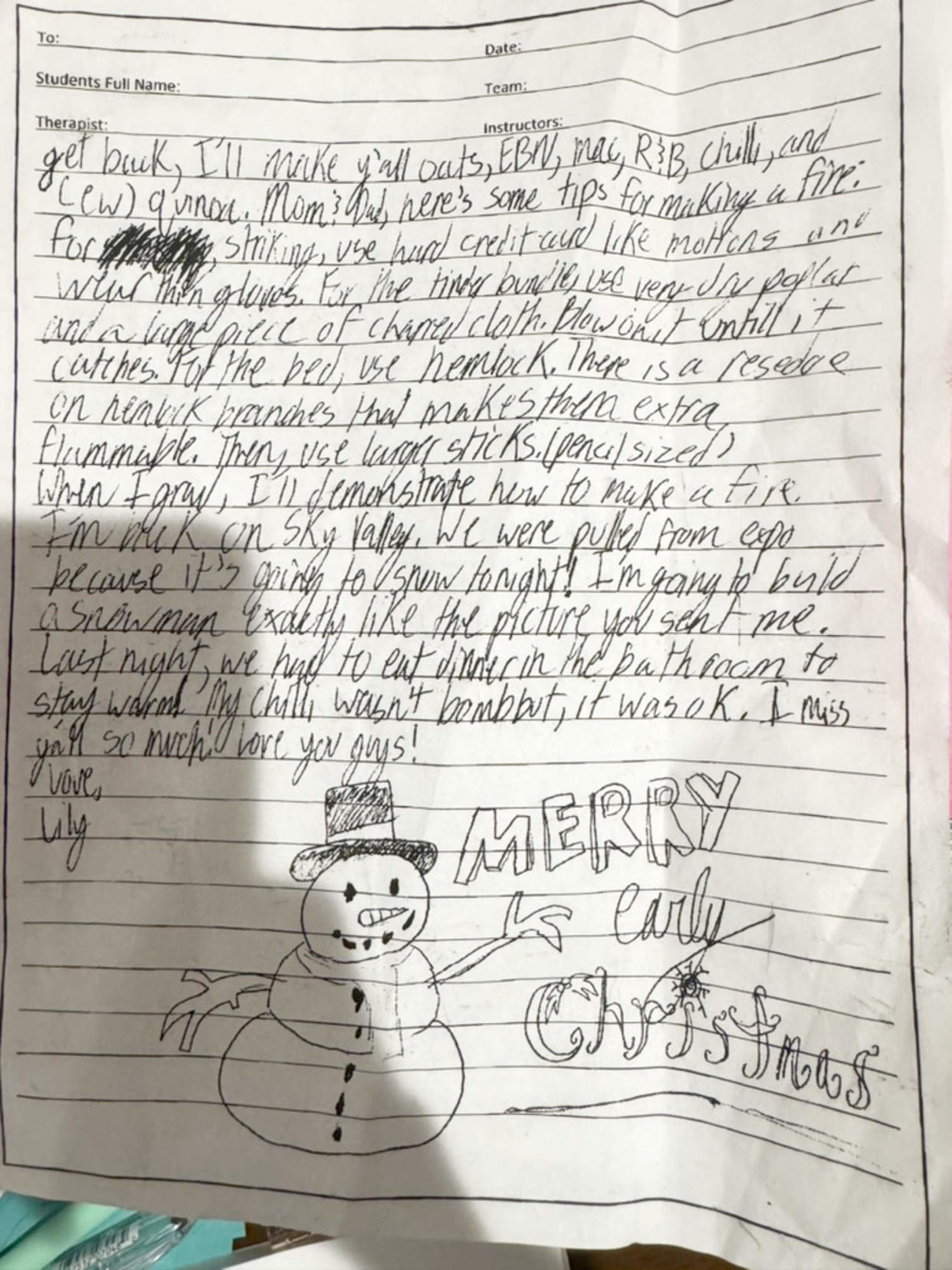

“The first thing I noticed was the smell — just a putrid mix of urine and B.O.,” said Lily, 18, who said she was sent to Trails Carolina in 2018 because her middle school kicked her out. She asked to only be identified by her first name to avoid damaging her college prospects.

“It was the worst smell I’ve ever smelled in my life,” she continued. “And then this little 10-year-old girl in my group comes up to me, looks at me and goes, ‘Wow, you’re so clean.’”

Lily, who was 13 at the time, said she soon learned that because staff limited the number of bathroom breaks on hikes, many children would wet themselves. The children were only able to shower about once a week, she and others recalled. Trails Carolina said that children on hikes were sometimes asked to wait to take bathroom breaks and said “everyone welcomes a shower and fresh clothes” after a hike.

“I just remember thinking, ‘Where the hell am I? What on Earth is this?’” Lily said.

After Burney arrived at Trails Carolina in 2016, she had no contact with her family for three long days. Finally, a staff member handed her a letter from her parents, which detailed the reasons they had sent her to the camp. Burney said she had to read it out loud to her new bunkmates, a practice the other former participants who spoke to NBC News also recounted.

“It is basically a letter telling you everything you’ve done wrong and putting all the blame on you,” Burney said. “It’s the first time you’re reading it, and the staff will tell you, you have to read it word for word.”

Seven of the former participants, who were there as recently as 2022, said on the first night, staff made children sleep in what the camp called a “burrito” — a tarp folded over their sleeping bag and tucked in — that restricted their ability to move. A staff member slept beside them on the tarp so they would wake up if a child tried to get out, according to the former participants and two former employees.

Alex Rudder, 23, said she was in the “burrito” not only on her first night, but also at other times, when she disobeyed or complained.

“You couldn’t sleep,” said Rudder, who went to Trails Carolina in 2017. “You’d sit there and have panic attacks all night.”

A lawsuit filed last month against Trails Carolina, by a former participant who alleged she was sexually assaulted by a girl in her camp group in 2016, also referenced the “burrito.” The suit said the camp placed the accused assailant inside a “burrito” multiple times so she could be “bound throughout the night” while field staff slept. The camp disputed the suit’s allegations in a court filing this week and asked that a judge dismiss it.

D’Alessandro said in a statement that the camp stopped using the “burrito” last year, though it was still used as a back-up “until recently.” It now uses “tent-like weather-proof covers to support the psychological and emotional well being” of the children, she said.

The 12-year-old boy’s death is the second since Trails Carolina opened in 2008. In 2014, a 17-year-old died from injuries he sustained after running away.

An inspection by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services last year found that children had attempted to flee or walk away without permission at least 21 times from March to June 2023 and were restrained following 20 of those incidents for anywhere from 10 seconds to 15 minutes. D’Alessandro said Trails Carolina uses restraints for children’s safety.

But advocates said the statistics indicate a problem.

“Trails Carolina needs to be shut down,” said Meg Appelgate, CEO of Unsilenced, a nonprofit that advocates for increased regulation of programs for at-risk youth. “If people are running away from ‘treatment,’ that indicates you’ve got a problem with that said treatment.”

Unsilenced has been campaigning for Congress to create the first federal law to regulate wilderness therapy camps like Trails Carolina, as well as other programs at boarding schools, residential treatment centers and ranches that make up the so-called troubled teen industry. Activism in recent years by former participants in these programs has caused state agencies to take tougher oversight actions.

Trails Carolina last year issued a press release acknowledging that the industry has had a history of abuse, but argued that its program is different. It said it uses “evidence-based practices,” and has “a commitment to the mental health of struggling adolescents, unlike the harmful, unregulated programs of the past.”

Following the 12-year-old’s death, the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, a nonprofit organization that certifies programs that meet certain standards, suspended Trails Carolina’s accreditation. Another accreditation group, the Association for Experiential Education, said it is collecting information to determine if it should take “further action” regarding Trails Carolina’s accreditation.

Four parents interviewed by NBC News who sent their children to Trails Carolina defended the program and said they hoped it would be allowed to reopen soon.

“I know it’s hard for other people to understand this,” said one mother, whose daughter was at Trails Carolina at the time of the boy’s death and has a history of depression and self-harming behaviors. “We have already been worried about our children taking their own life or doing something that causes them to lose their life. We’re in a very different place than, you know, the average parent.”

The mother, who lives in New England and asked not to be identified to protect her daughter’s privacy, said the camp had been a refuge “for parents who have tried everything they can.”

David Bloom, whose daughter attended Trails Carolina in 2022, said the program may not work for everyone, but for his child, “It just changed the whole trajectory of her life.”

“She had tools to manage her anxiety and tools to manage her anger,” said Bloom, who lives in New York. “She had hope that she didn’t have to live with these horrible, bad feelings forever.”

Like others who attended, his daughter had to read a letter aloud from her parents that outlined the reasons she had been sent to Trails Carolina, which Bloom said was “awful to write.” Yet, the letter and other challenging parts of the program do “have a therapeutic purpose,” he said.

“The way it was described to us is that every kid there is part of every kid’s therapy,” he said. “You’re learning from each other as much as from your therapist, or whatever the staff is on hand.”

Still, those who attended Trails told NBC News they felt abandoned and alone without their families.

“You don’t get to talk to your parents — only through letters,” said Zoe Aridas, 19, who attended Trails in 2019. “And if there’s something in those letters that they don’t want sent out to your parents or guardians, they take it out.”

Trails Carolina acknowledged in a 2023 court filing that letters written from children to their parents were screened by staff. After a licensing inspection in 2021, the state cited Trails Carolina for blocking some children from calling their families. The camp said in response that it would allow calls if the student’s therapist at the camp deemed them “therapeutically beneficial” and that parents would be notified if there were requests for contact that were denied.

In its statement to NBC News, Trails Carolina said it also allows Zoom and FaceTime calls, based on the children’s mental health and well-being. In response to questions about screening letters, Trails Carolina’s spokesperson said, “Asking students to ‘reconsider’ or ‘think about’ a statement they wrote teaches them to pause, process their emotions, and reflect on their actions.”

A week and a half into her stay at Trails Carolina, Burney got her period for the first time and said she was permitted to send a 40-second audio clip to her mom to inform her — but only if she also apologized to her family for her past behavior.

Burney shared the audio clip, in which her voice breaks as she says, “I’d really like some help from you and some support from you. I love you so much and I’m so sorry for the pain that I caused the family.”

Burney said she is still coping with trauma from her time at the camp.

“Things like that,” she said, “they are things that stick with you for the rest of your life.”