Titanic submersible: How sunken subs have been recovered in the past

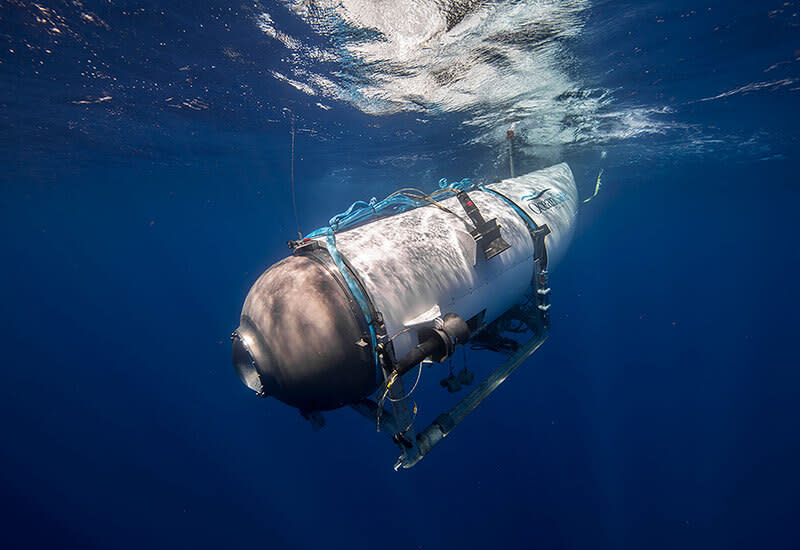

As rescuers continue to search for the missing submersible carrying five passengers who intended to visit the wreckage of the Titanic, naval experts have emphasized the challenges of a successful rescue operation.

Recovering underwater craft is always a tricky business, and the submersible that traveled to the Titanic went to such extreme depths that any rescue attempt would be extraordinarily difficult. Fifty years ago, the two-man crew of a small submersible was rescued off the coast of Ireland, but was in far shallower waters than the vessel that’s currently stuck somewhere in the vicinity of the Titanic.

When asked if they had the technology to perform a rescue if the craft is found, Coast Guard officials said they are taking things one step at a time and are currently focused on the search.

Here’s a look at some of the more noteworthy submarine salvage operations in history.

K-129

The Soviet Union lost contact with one of its ballistic missile submarines, the K-129, and its 98 crew members in March 1968 while it was in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The cause of the sinking is still a matter of contention; theories range from mechanical failure to a collision with another craft. The U.S. Navy found the wreckage of the sub 16,500 feet below the surface and, with the help of the CIA, embarked on a secret mission to recover the Soviet vessel and its nuclear warheads.

(Submersibles differ from submarines in that they do not have the ability to launch themselves and they require support ships. Submersibles are also generally smaller than submarines.)

In order to retrieve the sub from such a depth, the CIA settled on a plan — called Project Azorian — to build a large ship with a giant claw they would drop to the bottom of the ocean to retrieve the K-129. In order to cover up the real reason for the construction of the vehicle, they sought the assistance of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, implying the Hughes Glomar Explorer was being built to do deep sea mining.

In 1974, the Explorer made its way to the salvage site (while being monitored by the Soviets) and deployed the giant claw, which was nicknamed “Clementine.” As the sub was being slowly hauled up, the claw malfunctioned, with much of K-129 sinking back down. The remains of six crew members were recovered and given a burial at sea with full military honors.

The effort to return for the rest of the wreckage, known as Operation Matador, was proceeding when reporters broke the story of the covert salvage operation in 1975. In response to a request for documents pertaining to the operation, the CIA said they could neither confirm nor deny their existence, leading to the popularization of that term.

K-141 Kursk

In August 2000, the Russian Navy was conducting exercises in the Barents Sea, a body of water bordering the country’s northwest corner. The Kursk, with 118 crew members on board, went down after two explosions, which investigators say was likely caused by a peroxide leak in a faulty test torpedo.

Despite the fleet noting the explosions, it took hours for naval leadership to realize something had happened to the Kursk and even longer for them to begin searching for it.

The submarine had settled about 350 feet deep and initial Russian rescue operations faltered as they declined offers of assistance from foreign governments. Vladimir Putin, newly installed as Russia’s leader, belatedly accepted help from Great Britain and Norway days after the accident.

A week after it went down, divers cut their way into the Kursk and found there were no survivors. Investigators later found that 23 crew members survived the initial blast and had gathered near the rear of the sub but were killed by a fire and lack of oxygen.

Russian naval leadership initially blamed the sinking on a collision with a NATO craft, but never provided any evidence to support this claim. The Kursk did have a rescue buoy that would have automatically activated if it detected an emergency, but it had been disabled the year prior when it was deployed in the Mediterranean.

Most of the ship's hull and the remains of 115 crew members were recovered in October 2001.

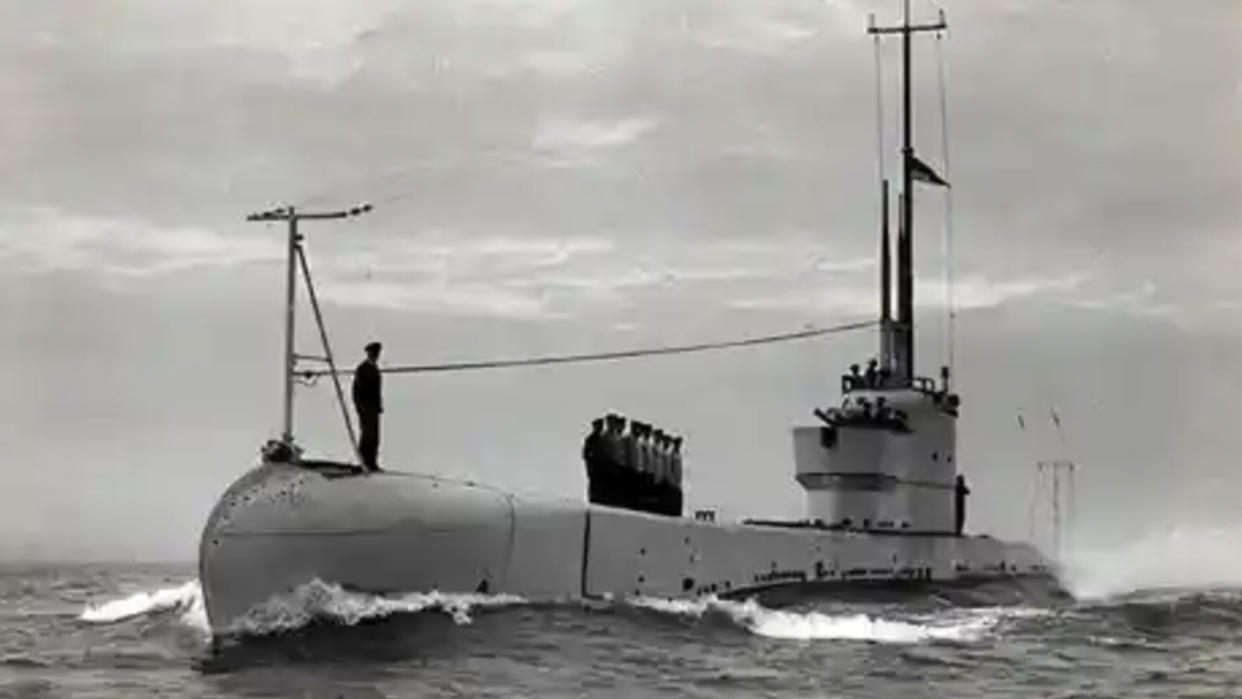

HMS Poseidon

The HMS Poseidon, a submarine in the British Royal Navy, collided with a cargo ship off the coast of China in June 1931 and sustained catastrophic damage. Because it was surfaced at the time, a number of the crew members were able to escape, although 21 sailors died, either from being trapped in the vessel or being unable to survive the escape.

Some crew members successfully made it from the sinking ship to the surface using a Davis lung, a predecessor to modern scuba gear. This led to a shift in naval policy encouraging attempts at evacuation versus waiting for rescue, including the addition of escape chambers to make doing so possible.

The Chinese government quietly began a recovery operation of the Poseidon in 1972. While a Chinese naval magazine reported on the salvage effort three decades later, it wasn’t widely known until Steven Schwankert, a Beijing-based American author and diving instructor, came across references to the article on Google .

His research led to a book, “Poseidon: China’s Secret Salvage of Britain’s Lost Submarine,” and a 2013 documentary film, “The Poseidon Project.” The Chinese government admitted to the salvage operation in 2009, claiming they hadn’t come across any remains or personal items belonging to the British sailors.