'Titane' director on the queer body horror film seducing critics, bewildering audiences

Unabashedly violent and full of big ideas, this year’s Cannes Palme d’Or winner, “Titane,” directed by Julia Ducournau, has stunned its way into becoming one of the year’s most notable films. On Tuesday, the film was selected as France’s official Oscar submission, beating out Venice Golden Lion winner “Happening” and “The Stronghold” in a competitive race.

Only the second woman to win Cannes’ top honor, Ducournau taps into audiences’ taste for blood — something her debut film, “Raw,” had in abundance — while subverting the modes of arthouse and blockbuster horror. And she’s being rewarded at the box office, setting recent records for both French-language films and Palme d’Or winners.

In “Titane,” Ducournau’s critical lens is focused on exploitations of gender and queerness. To that end, there’s an abundance of body horror that pulls on the physical pain of pregnancy and abortion, binding and hormone injections. Ducournau, in her usual style, toes the line between fantasy and reality with these warped images, which makes them all the more cringeworthy.

But it’s not just body horror — pregnant breasts engorged with motor oil, metal tearing through skin, cranial fluid frothing out of a punctured ear — that’s causing viewers to squirm in their seats. The lead character, Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), is a gender-bending, violent psychopath who elicits a fair amount of shock as well. She views human life with the same apathy as gender, which, in most horror films, would require her to be the villain.

“From the get-go, I absolutely did not want to justify my character’s violence, and I did not want to psychologize the fact that she’s a psychopath,” Ducournau told NBC News.

“When women kill in movies, it is very often linked to a cause that is explained. There is a justification. Men can be inherently violent for no reason, but for women it is utterly unacceptable,” she said.

With Alexia, someone who can kill with “no emotion, no justification,” Ducournau said she wanted to break with the social construct that women are designated victims who can’t or won’t retaliate.

With pulsing music, minimal dialogue and plenty of shock value, the film creates a world where people can defy categorization and violence without reason is always lurking in the shadows.

'Reclaim[ing] the narrative over the patriarchy'

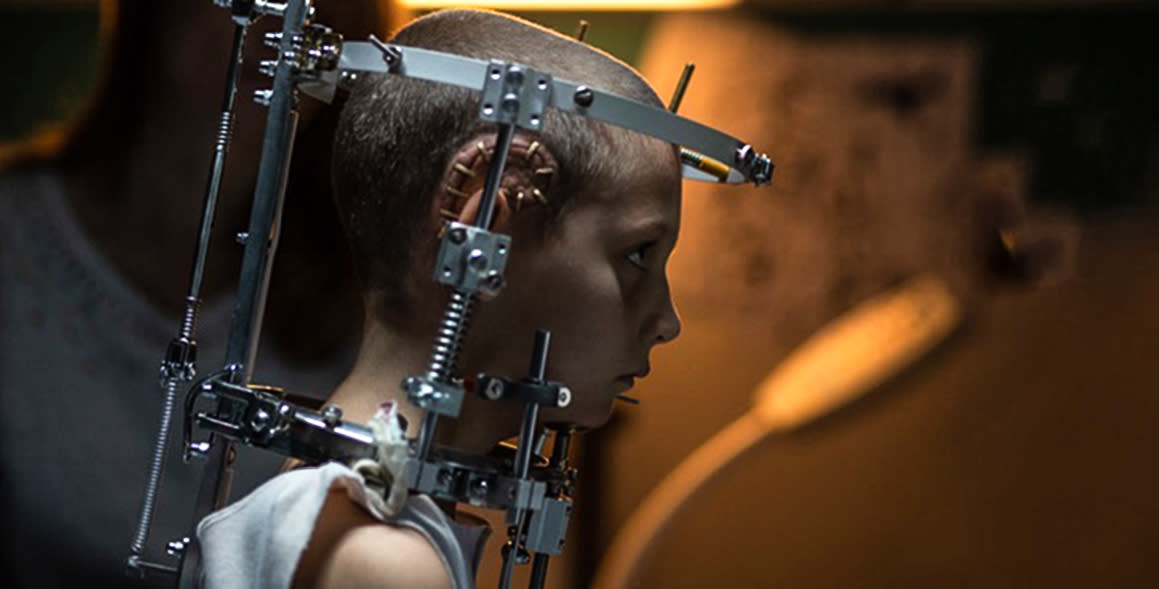

The film opens with a violent car crash involving a young Alexia and her father, who seethes with disdain at his daughter's image in the rearview mirror moments before her head nearly breaks through the window. He walks away unscathed, while she ends up with a titanium plate in her head and a dangerous attraction to motor vehicles.

In dizzying order, the film begins to unfold, layering metaphors on arresting visuals. Adult Alexia, sporting a sci-fi head scar, slinks through a car show filled with writhing women and sordid men to the film’s seductive opening score. Ducournau’s skill with choreographed chaos is on display as Alexia performs a stone-faced Dance of the Seven Veils on top of a flame-decorated hood, both women masterfully luring their audience in. But, buyer beware: Alexia’s enthusiasm for cars is matched by her indifference for people.

The murdering begins when a threatening fan who stalks Alexia outside of the show is quickly disposed of with a hair pin, reminiscent of the ice pick scene in “Basic Instinct.” But things really begin to unravel when, afterward, Alexia has what can only be described as a sexual encounter with one of the cars and becomes pregnant.

It’s the most talked about scene in the film and one that has been read as its queerest. Elsewhere in the film, gender and sexuality are expressed in more conventional terms, even when they’re being subverted. But here, heteronormative and nonheteronormative labels don’t really apply.

It’s also another example of Ducournau’s particular brand of subversion: taking a symbol and stretching it to its most perverse and fantastical ends.

“This very active, very devouring relationship with the car makes her reclaim the narrative over the patriarchy and makes her own desire prevail over a symbol of masculinity,” Ducournau said.

The resulting corrosive resident of her womb seems to trigger something animal, rather than maternal, and midway through the film, Alexia is a regular Jack the Ripper. As the bodies pile up, she’s forced to go on the run and forms a plan to obscure her identity and masquerade as a missing person, Adrien, whose poster she spots next to her wanted one.

Despite the obvious farce, the missing boy’s father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), wholeheartedly welcomes the return of the prodigal son, and Alexia finds refuge as Alexia-Adrien.

'A character that evolves beyond gender'

The Alexia-Adrien storyline is perhaps Ducournau’s boldest move in an already ambitious film. At different times, it feels provocative, callous and merely laughable.

In a gruesome but darkly comical scene, Alexia performs homemade facial reconstruction a la a bathroom sink, the results of which look nothing like the Adrien from the missing poster. This lack of resemblance becomes the film’s longest-running joke, setting up a slew of punchlines at the firehouse where Vincent is the much-loved, much-feared captain.

The film has also drawn criticism for employing the trans tropes of binding and hormone injection to its own ends. As father and son settle into the charade, they perform rituals that help maintain the illusion: Alexia-Adrien binds to hide an increasingly Madonna-esque body ripping at the seams, and Vincent, an aging alpha, injects himself with steroids that pulsate through engorged veins.

Ducournau said the film’s presentation of gender is not part of an agenda but rather born out of realizations that she had long ago about her own identity: “that my gender was something that is purely a social construct and that it somehow limited me as an individual,” she said. Alexia is an extreme embodiment of that philosophy, having “no attachment to any gender,” as Ducournau described her.

“While trying to question and debunk and subvert the gender stereotypes, I tried to also portray a world where there are more options, and we actually do not need to evolve in two genders, which are incredibly limiting,” Ducournau said. “Having a character that evolves beyond gender was absolutely normal.”

Ducournau said this evolution was also key to the film’s exploration of unconditional love, which she described as “love that can see past representations and all forms of determinism.” Although Vincent clings to the idea that Alexia-Adrien is really his missing child, the pair’s bond strengthens as the veil continuously slips and eventually falls.