She founded adult education with ‘Moonlight Schools.’ Yet today we hardly know her name. | Opinion

Kentucky labors under stereotypes of backwardness but deserves to be known for its unsung initiatives and profound movements like the Packhorse Librarian Project or the Frontier Nursing Service, which were women-driven and saved lives of those living in abject poverty in Eastern Kentucky.

But when researching my latest book, I dug deeper into an even more obscure, but wildly successful literacy campaign founded by a Kentucky woman known as “the Moonlight Lady.” She was such an inspiration and left an important footprint that I was inspired to buy her a grave marker 65 years after her death. An unsettling reminder in the first days of Women’s History Month of how far women have come and how much further we need to go.

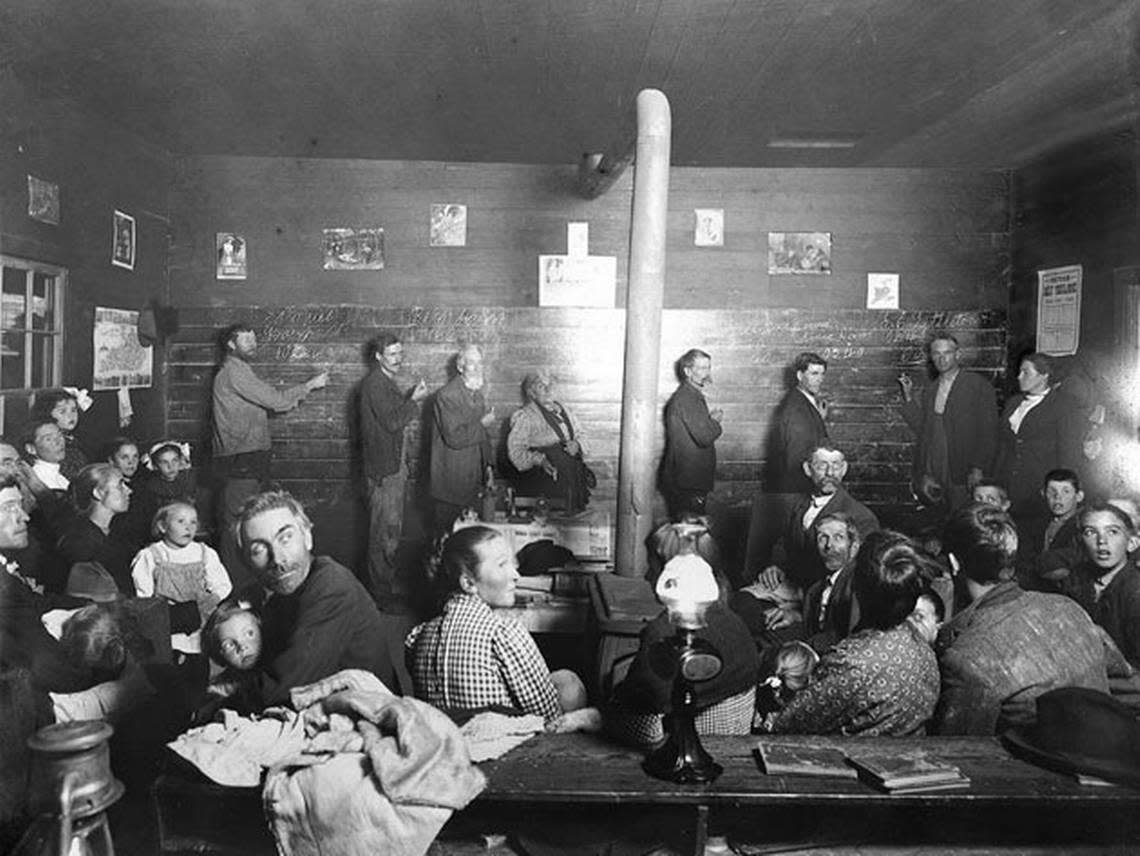

On Sept. 5, 1911, Cora Wilson Stewart (1875-1958) opened her first Moonlight School in Rowan County, Kentucky. That first night 1,200 adults showed up. They came in droves from Kentucky’s dark hollers, needle-eyed coves and tree-thick hills. Born in Farmers, Kentucky, Stewart led the nation’s first official campaign to fight adult illiteracy.

Many attendees of the Moonlight Schools were coal miners, lumber workers or farmers by day. The adult students became known as Moonlighters, and would walk miles to class on nights when the moon was bright enough to light the dark, tricky paths. They attended the short sessions during the bone-shivering winters, green carpeted springs and sticky hot summers. Their ages ranged from 18 to 86. Some walked with canes, others toted babies after a long day’s work, many chanting along the paths a favorite poem they were taught, The Ladder of St. Augustine by Wadsworth:

“The heights by great men reached and kept

Were not attained by sudden flight

But they, while their companions slept,

Were toiling upward in the night.”

Fortified with these skills, the adults were able to stand up to the big lumber and coal companies that exploited them. The Moonlight Schools impacted millions of underserved Americans including soldiers, incarcerated men and women, crossing racial barriers with disfranchised Native Americans and Black citizens.

Stewart devised a simple teaching method for adults that included a beginner’s tablet, half which was made of grooved pads of delicate, colored blotting papers containing the alphabet which students traced. Students first learned to etch the letters and then their names until they could write them without aid. The rest of the tablet contained plain paper, widely spaced, on which they copied script from Stewart’s The Country Life Reader. She refused to use childish readers about puppies and kittens that might feel demeaning and strip away the dignity of adults, and, instead used newsprint and booklets she developed specifically for her Moonlighters. Decades later, civil rights leaders registering Black voters deployed Stewart’s technique to help them access the vote.

When young men registered for the draft in WWI, 700,000 were found lacking in basic literacy. About 30,000 of those men were from Kentucky and could only sign their name with a mark. Stewart organized volunteers across the state to offer accelerated literacy sessions prior to the men leaving for military duty.

In 1913, Stewart’s Moonlight Schools began spreading to other states. By 1916, additional states, including New York, California, Massachusetts, Maryland, Texas, New Mexico, the Dakotas and Carolinas, Oklahoma, and Georgia, heard about the successful Kentucky program and adopted Stewart’s Moonlight Schools. More states would follow. Hundreds of thousands attended the Moonlight Schools over their first 20 years. It is significant that Stewart chose New England abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, “Our State,” as a motto and the first reading lesson for her Moonlight Schools—the gift of reading is priceless:

“The riches of the Commonwealth

Are free, strong minds and hearts of health,

And dearer far than gold or grain

Are cunning hand and cultured brain.”

In 1915, realizing the link between crime and illiteracy, she championed for the incarcerated. Feeling their wrongdoings were the result of being shackled by illiteracy, Stewart enlisted Kentucky jailers and prison wardens to recognize the value of the Moonlight Schools and add her classes. They readily agreed, and soon other state and federal prisons followed, making it a prerequisite to learn to read and write before an inmate could apply for parole.

Cora Wilson Stewart drew attention to the scourge of adult illiteracy and millions of lives were changed. Her teaching methods would be revised and updated over time, but the point was not to need them. In 1926, she founded the National Illiteracy Crusade and became the Kentucky Education Association’s first female president. She also chaired Herbert Hoover’s Commission on Illiteracy and persuaded women’s groups, legislators and large corporations to fund public service campaigns against illiteracy.

Stewart achieved astonishing feats as a professional educator at a time when women were not allowed to vote and were steered straight into marriage and motherhood. But her personal life was met with much tragedy and sorrow. She survived domestic violence, marrying three times, twice with the same man. Their only child died just months before his first birthday. By 1953, Stewart suffered total blindness and was infirmed. Her last address was a rented room at the Oak Hall Hotel in Tyron, NC.

Little did I know when I wrote about the unique night schools in my latest novel, The Book Woman’s Daughter, I would receive inquiries from across the country and abroad for information about the founder whose grave is marked with a stone not much bigger than a brick that excises her full name and fails to recognize her selfless, successful crusade for literacy.

I couldn’t stop thinking about this woman’s final resting place. If she had been a man, a monument would have been erected. That a prolific educator who freed countless people from the bondage of illiteracy and crushing poverty, ended up with less than a final footnote of recognition in a cemetery.

It’s also a reminder of my state capitol’s Rotunda and the all-male, bronze statues honored inside, like a lot of other state capitols. I think about the thousands of students, especially young girls who visit yearly and wonder what they must think when they don’t see a statue like them. If their echoes in history will be lost like Cora’s. As a woman, I knew it was important to somehow right another sister’s legacy, and although Cora’s cemetery doesn’t allow standing headstones, I purchased a large decorative marker with vase and etched book that recognizes her priceless contribution to the world.

As a Kentucky author with deep love for educators and the written word, I knew Cora needed a proper grave marker that recognized her lifelong battle to stamp out illiteracy. She called it, “a war without the loss of human blood, without the click of a gun or the firing of a cannon—a war fought with the book and pen.”

For many it was the war of one brave woman with an unwavering, crusading spirit who was no doubt doing the work of a five-star general.

Kim Michele Richardson is the award-winning author of “The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek” series, and founder of Shy Rabbit, a writers residency scholarship that promotes underserved artists. She is a native-born Kentuckian who resides in Kentucky. www.kimmichelerichardson.com.