Robert McNamara waged war on Vietnam. His son is a California farmer facing that legacy

The Vietnam War officially ended in 1975. But for millions of Americans who served or had loved ones fighting in that bloody mess, it rages on.

One of those Americans is Craig McNamara.

Does that name sound familiar? That may be because Craig McNamara’s father, Robert S. McNamara, was secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968.

Opinion

Secretary McNamara was arguably the man who, along with President Lyndon Johnson, crafted the debacle. He also spent the rest of his life analyzing it, attempting to atone for it and trying to explain it, to limited effect.

Craig McNamara’s new memoir, “Because Our Fathers Lied,” is a riveting and unsparing, painful and frank, emotional and empathetic journey through the morass of a father-son relationship and a war that sucked millions of lives away for no explicable reason.

“My entire life has been lived through the lens of the Vietnam War,” he told me.

Startling resemblance

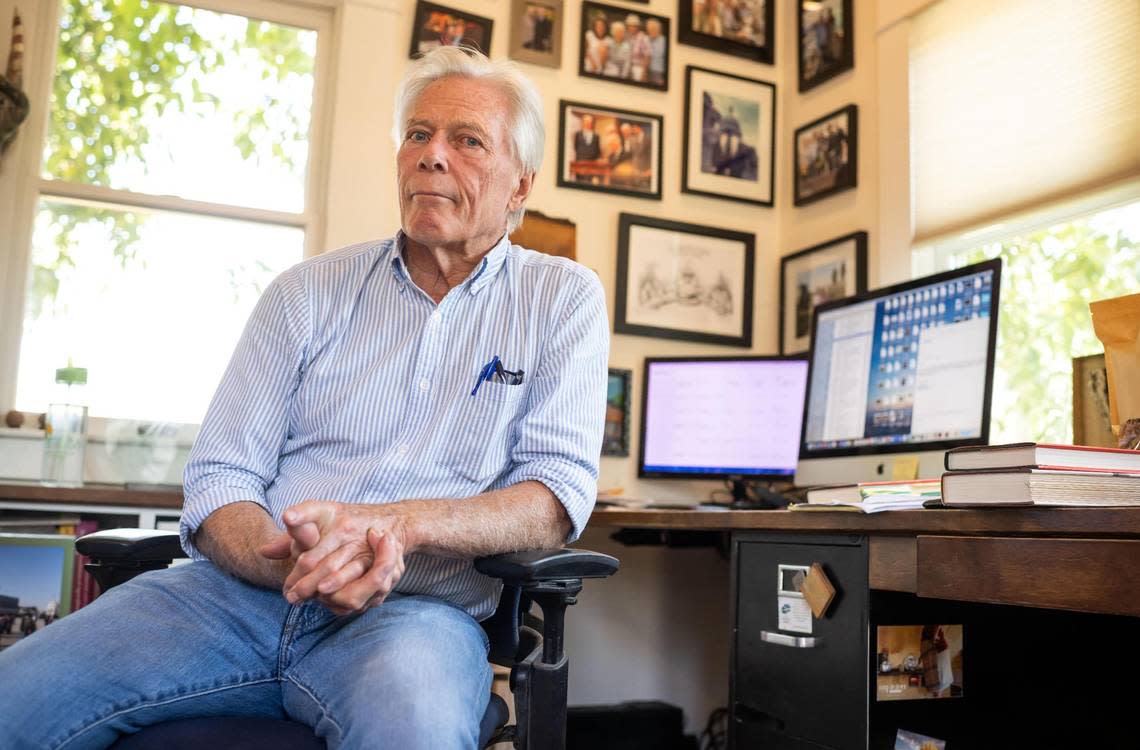

In stark contrast to his father’s action-packed power corridors, Craig McNamara lives a quiet life in Winters, where he owns a walnut orchard and is a recognized expert on sustainable agriculture.

He’s 72 now, with piercing blue eyes, a trim physique and, at times, a startling resemblance to his father, who died in 2009.

McNamara was a Camelot cabinet kid; he played with Caroline and John-John, hung out at the pool with Robert F. Kennedy’s children at their Hickory Hill estate and sat with JFK for a screening of “PT-109,” the 1963 film about his experience in World War II. He even got a letter from the president’s son, dictated to Jacqueline Kennedy after the assassination, complete with airplane and shark drawings.

After Secretary McNamara left the government to begin a 13-year tenure as president of the World Bank, young Craig McNamara went on a tour of self-discovery of the kind that wasn’t unusual during the 1960s. He dropped out of Stanford, rode a motorcycle through Central America, lived on Easter Island and smoked weed.

Having taken the military entrance physical and been classified 4-F (not qualified for service) due to an ulcer, he ultimately wound up with a degree in plant and soil sciences from UC Davis. It was there that he learned the skills that made his Solano County farm, Sierra Orchards, a sustainable if not terribly lucrative walnut and olive oil operation.

His father’s chair

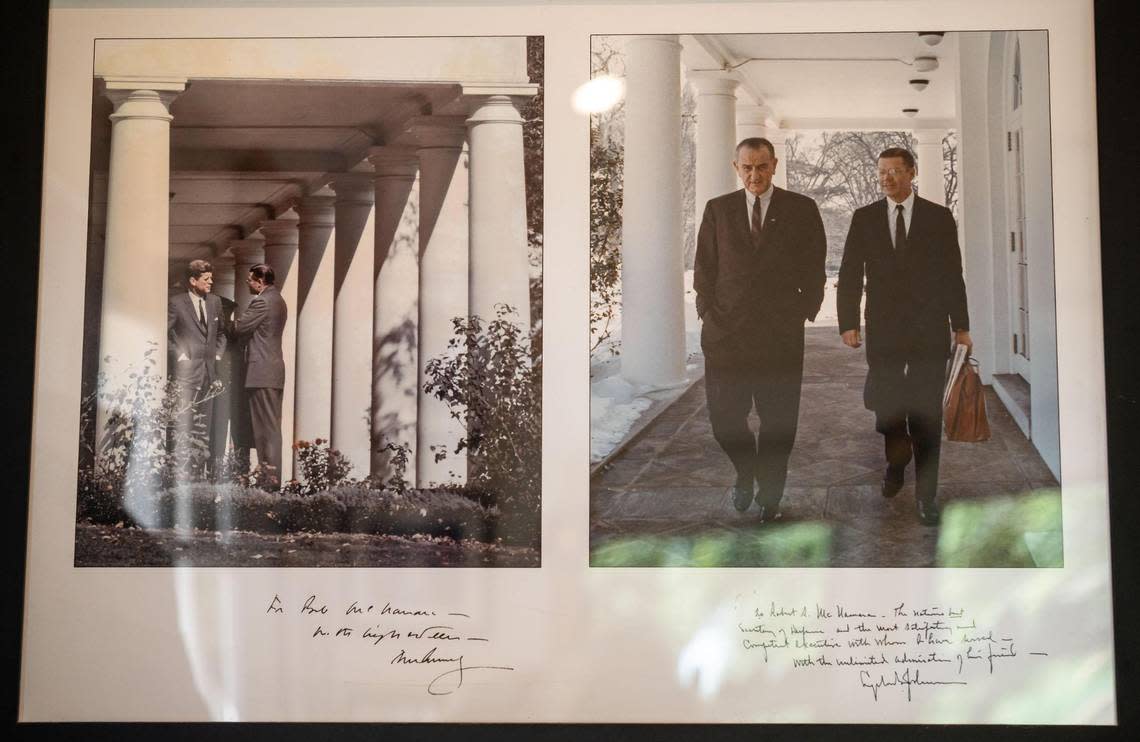

Today the walls of his office bear the artifacts of his father’s career and his own, an oxymoronic clash of 1960s political power and 1960s counterculture. Photographs of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, signed for his father, hang alongside original R. Crumb cartoons.

A battered chair upholstered with “Mad Men”-era teal leather is also there. I was sitting in it without thinking about it before McNamara told me it had been his father’s office chair. He turned it around to reveal a plaque that reads: “Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, 1961-1968.” The family of one of McNamara’s assistants ended up with the chair and almost threw it out.

It was in this chair that Secretary McNamara sat during pivotal moments of his career: while navigating the Cuban Missile Crisis, sending advisers to Vietnam and escalating the war. And he was sitting in it when a man named Norman Morrison immolated himself to death outside his Pentagon office to protest the war.

History becomes very real when you can touch the artifacts and consider the life of a complicated man who failed at a critical moment — failed to stop a war he knew to be unwinnable as early as 1963 even though he said, well, nothing.

Craig McNamara goes further than that in his memoir, calling his father a war criminal. I asked him, “Did you ever really say to your father, ‘I think you’re a war criminal’?”

“No, no, no, no, no,” he said. He loved his father and spent years trying to get through to him on every level — a common experience for baby boomers raised by the wary men who lived through the Great Depression and World War II. In some ways, Robert McNamara was a good father, taking his wife and children on countless hikes and backpacking trips, experiences his son still cherishes decades later.

Fog of war

So why this book now?

McNamara enrolled in the Stanford Distinguished Careers Institute for 2018, and he and his wife, Julie, decided to study writing.

“It did start me on this journey,” he said. “I knew I wanted to write this memoir, but technically, I didn’t know how … to relieve myself of this story.”

McNamara then brought out a large piece of brown butcher block paper, unfurled it on the floor, and walked me through a free-associative maze of a diagram. A young Stanford writing teacher had asked him to conjure memories of his early life in Michigan and diagram them this way, which helped him realize that he could write a memoir. He also relied on the advice of Rose Styron, the poet and widow of the Pulitzer Prize-winning author William Styron.

I asked McNamara what his father would have thought of the book.

“I tend to think it would have created the moment that I — he and I — we wanted, (and) I believe he would think this was really hard,” he said. “This would be devastating.”

Did Robert McNamara consider whether he was a war criminal? His son noted that he did address the subject in Errol Morris’ documentary “The Fog of War.” The former defense secretary told Morris that Gen. Curtis LeMay had said that those responsible for the firebombing of Japanese cities during World War II — among them McNamara, then an Air Force officer under LeMay — would have been charged as war criminals if they had been on the losing side, an assessment with which McNamara agreed.

What did Morris think of his father?

“I said, ‘Errol, I have people in my life now who I believe are evil. … Do you believe people are evil?’ “ Craig McNamara recalled of a conversation with the filmmaker. “And he said, ‘I don’t believe people are evil. I believe that people do evil things.’ “ Morris went on to say that he loved McNamara despite Vietnam.

“That (conversation), believe it or not, allowed me to realize that I love my father,” McNamara said.

What if?

His memoir abounds with what-ifs. For example, President Kennedy offered either the Defense Department or the Treasury Department to Robert McNamara, who was president of Ford Motor Co. in 1960. He seemed perfectly qualified to lead either, his son said. Of the Treasury position, he said, “He was very well-positioned for that job as a statistician, you know … had the memory, the math, Whiz Kid, all that.”

What if McNamara had taken Treasury instead?

It’s likely that the same Cold War mentality would have been present under, say, Robert Lovett, who was also under consideration for Defense. In 1961, it wasn’t just solely McNamara’s view that communism must be contained; that was a central tenet of postwar U.S. defense policy, one to which Lyndon Johnson wholeheartedly subscribed.

Intriguingly, the younger McNamara has become close friends with Daniel Ellsberg, the Rand Corp. analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971, laying bare his father’s duplicity. There may be an element of atonement in that relationship — a son reaching out to his father’s critics in order to better understand him.

One of the common threads of McNamara’s book is his coming to grips with the physical artifacts of his father’s life, two poignant examples of which come to mind.

McNamara’s second wife sent all the defense secretary’s artifacts to Sotheby’s for auction. Two chairs that Kennedy and McNamara sat in during pivotal meetings were among them. They went for — are you sitting down? — $146,500.

The winning bidder gave them to a Vietnamese visual artist, Danh Vo, who proceeded to tear the upholstery off and turn them into an art installation. Craig McNamara’s reaction? He befriended Vo, who even visited him at his orchard in Winters.

A small, sterling silver calendar highlighting the thirteen days of the October 1962 missile crisis, commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy and made by Tiffany, was also put up for auction. McNamara and his sisters decided to bid on it. Their ceiling was $15,000; they paid $77,000.

McNamara handles it like something from a reliquary. It is worn and tarnished, but his eyes told me it was worth every dime to have a physical connection to his late father’s greatest triumph: saving the world from a nuclear holocaust.

After the orchard

Craig McNamara’s orchard is 65 years old, at the end of its natural lifespan. Coincidentally, about the same amount of time has passed since Robert S. McNamara became secretary of defense. His son struggles with questions about what comes after the orchard, a living entity that he, his wife and children have worked on for 42 years.

“We’ve got to remove it all,” he said. “What do you do (next) in this time of climate change?”

McNamara is trying to remove the aged tangle of his father’s legacy and his orchard, his life lived well and faithfully as an unpretentious farmer and advocate, an atonement of sorts he says he didn’t consider much until I mentioned it.

Robert McNamara tried to atone. Perhaps Craig McNamara, along with his sisters, wife and children, are doing the same for their father and grandfather by other means. A new purpose for the land, as for the McNamara family, will emerge.