Once an Underground Railroad stop, the Quindaro Ruins are languishing in Kansas. Why?

The Rev. Stacy Evans was stuck.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church pastor gripped the wheel of a gas-powered Club Car — imagine a golf cart with attitude – as she tried to climb out of a muddy ravine in the thick forest that covers the Quindaro Ruins. No matter the approach, the tires, unable to gain traction, kept spinning.

Evans has spent years among the ruins, the stone and brick remnants of a Civil War era boomtown in Wyandotte County and an outpost along the Underground Railroad that moved enslaved people to freedom. She watches over dozens of acres that bear the marks of a vanished town and signs of the fraught modern-day effort to bring its full legacy into the light.

On a recent warm Saturday morning in June, Evans was overseeing about a dozen volunteers picking up trash in honor of Juneteenth, which commemorates the day when enslaved Black people in Galveston, Texas learned of their freedom months after the Civil War. She used the Club Car to drive between work sites, ferrying trash bags and tools to where they were needed.

Volunteers last summer deployed a forestry mower to cut trails through the site, using the layout of the town as a guide. This summer, they are clearing away tires, soda cans, glass bottles and other debris scattered along the sides of the trails. But they have to pay attention; among the junk could be 19th century artifacts worth preserving.

As Evans’ wheels began to spin and fishtail in the mud, it appeared as if the vehicle would tip over. Evans was unfazed, noting several times she had successfully navigated the same terrain a year earlier. Sure enough, after a few minutes she found a path out of the ravine.

More than 30 years have passed since a failed push for a landfill on the site resulted in archaeological excavation that began to unearth the ruins. Even as Black leaders in Wyandotte County and across the Kansas City metro broadly agree on the importance of the site as a powerful monument to extraordinary Civil War-era efforts to bring Black people out of slavery and create a more just society, actual forward movement remains halting.

Interviews with nearly 20 advocates, descendants of Quindaro’s first residents, politicians, historians and others show that no single factor explains why the cause of preservation has been so difficult. Missed opportunities, weak organization and racism have all played a role — the effects of each compounding in ways that today are difficult to fully untangle.

Preservation of the historical site is viewed by many as a pathway to improving life within the Quindaro neighborhood, bringing jobs and tourism to one of the state’s most impoverished areas.

Evans, who chairs the Quindaro Ruins Project Foundation board, has been helping to spearhead efforts to preserve Quindaro since 2009. At 57, she’s more optimistic than ever that the site will eventually come to the national prominence that area Black leaders believe it deserves.

“Sometimes I get weary, but I can’t – I’m going to do it until it’s finished,” Evans said.

It’s been a rough path.

Decades ago, the remains of an old brewery were stabilized, with steel and concrete and pillars holding in place old stone. But other buildings are still unstabilized and other structures haven’t been excavated at all. Every year that passes without stabilization of the ruins leaves the area vulnerable to irreparable damage from the elements.

Congress designated Quindaro a National Commemorative Site in 2019 – a major achievement it shares with just one other historical site — but the recognition did not directly provide nor has it translated into substantial new funding.

“The progress is very slow,” said LaVert Murray, an economic development advisor for the Unified Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas, who has been deeply involved in efforts to preserve the site.

Evans and others envision a world-class destination with ADA-accessible trails, stabilized ruins and a center to showcase artifacts. All of it would take tens of millions of dollars. They hope that someday the National Park Service might even run the site.

Still, divisions exist within the community of advocates who have taken up the Quindaro cause. Like any passionate group, personalities sometimes conflict and not everyone has always been on the same page. Longstanding skepticism of the AME Church in the area, driven by its handling of the site and its role in the failed landfill project, has also hampered efforts to create a unified preservation effort.

Add to that a sense, Evans said, that organizations with grants to give that could have a transformative impact want to “force us to work together in ways that haven’t been natural.” These organizations, she said, haven’t trusted a collection of small, Black-led, nonprofits.

This spring, the Republican-controlled Kansas Legislature appropriated $250,000 for the development of a strategic plan for the site after state Rep. Marvin Robinson, a Kansas City Democrat who has spent decades advocating for Quindaro, voted with Republicans to override Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly’s vetoes of legislation regulating the lives of transgender residents.

Robinson also delivered a key vote for Republicans on a bill to increase work requirements for older adults on food stamps, a policy that is likely to have a disproportionate impact on the economically-disadvantaged neighborhoods he represents.

Kelly vetoed the earmark, a controversial decision that has led to a new wave of attention on the site, of which many Kansans remain unaware. The veto has also served as a reminder of just how arduous the process of preserving Quindaro has been and how advocates have struggled, often in vain, for more resources.

Decades into efforts to restore and preserve Quindaro, state Sen. David Haley, a Kansas City Democrat whose district includes Quindaro, recently voiced frustration with the lack of resources.

“It does beg the question,” Haley said. “How shallow can our governmental entities be to not recognize the tremendous tourism and historic significance and to develop the site for the glory of KCK, the glory of Kansas and those who follow and enjoy a rich history?”

‘Our rich history’

Anthony Hope sees the potential future glory of Quindaro every time he visits the site.

Hope, president of the group Concerned Citizens for Old Quindaro Museum, wants Quindaro to one day become a tourist attraction where “we could tell the people of our rich history.”

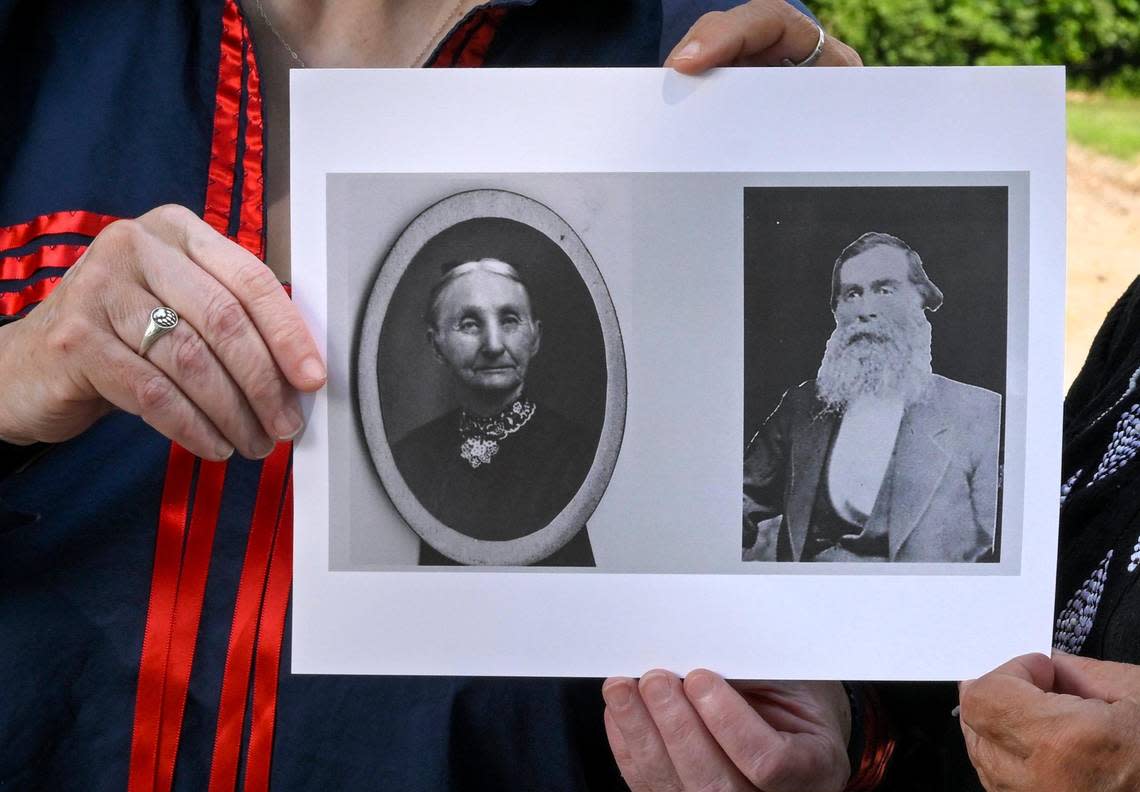

Hope’s great-great grandfather arrived in Quindaro after escaping slavery in Missouri. His family has lived in the Quindaro area in Kansas City, Kansas, ever since and many of his ancestors are buried in a cemetery on a hill in Quindaro overlooking the Missouri River and Parkville to the north. Hope, 61, will also one day be buried there.

“All my life, my family has fought to bring more awareness to Quindaro and this whole area,” Hope said. “But it seems like the funds have always slipped and went by the other way.”

The Quindaro townsite dates back to the mid-1850s, with Free Staters, who opposed slavery, purchasing land from members of the Wyandot tribe near the southern bank of the Missouri River. The ruins today sit north and west of I-635 south of the river.

The town quickly grew to about 600 residents, in part by settlers who had traveled to the area with the goal of ensuring Kansas — then a territory — would be admitted to the Union as a free state. With a port and its location near the border of the slave state of Missouri, it also became a stop along the Underground Railroad — part of a network of safe houses that helped shepherd enslaved people toward freedom, often in northern states or Canada.

It was the location of the first known emancipation in Kansas, nearly three years before President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Wiley M. Pope, a white man who fled from Missouri to Kansas with Lucy, a Black woman he had owned as an enslaved person and then married, and their 11 children.

Judge Charles Chadwick, of Quindaro, signed a deed of emancipation for Lucy and her children in 1860 and the residents of the town pledged to protect the Pope family if southerners sought to return them to slavery. Many of the first Black men to fight in the Civil War as part of the First Colored Infantry were also from Quindaro.

But the town in 1863 began a rapid decline amid an economic depression and a lack of a railroad, according to the Kansas Historical Society. Many young men went off to fight in the Civil War and while some families continued to farm in the area, the original town was largely abandoned.

Nearby, the Quindaro Freedman’s School, which taught the children of formerly enslaved people, was founded in 1865. It eventually became Western University, the first historically-Black college west of the Mississippi River supported by the AME Church that closed in 1943. None of its buildings remain but a statue of the abolitionist John Brown still stands on what was the campus.

The area was also home to Douglas Hospital, where Hope and Robinson were born. The hospital was the first Black hospital west of the Mississippi River, opening in 1898 and closing its doors in 1977 after desegregation efforts slowly pushed the hospital out of business.

Today, the Quindaro neighborhood is one of the most economically disadvantaged areas in Kansas. According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, 32.6% of residents in Quindaro’s census tract lived below the poverty line in 2021 compared to less than 12% statewide and 15.9% in Wyandotte County. More than 20% of the neighborhood’s residents lack health insurance.

Hope and others have attempted to keep the memory of the area alive through the Old Quindaro Museum, located in a historic house in the present-day Quindaro neighborhood. However, the museum has been closed for several years because the house is in disrepair.

Concerned Citizens for Old Quindaro Museum has been raising funds, including holding a benefit concert earlier this month. Hope estimates the house needs $60,000 of work. The organization so far has raised about $2,000 and is still accepting donations, he said.

“When we first got it, it wasn’t this bad but we kept passing it and passing it. But this makes me want to cry, you know, because … my family ate dinner in this home and it was the showplace of Quindaro for many years,” Hope said.

Racism’s role

Holly Zane, a member of the Wyandot tribe, was told by her father on his deathbed that he wanted Zane and her sister to continue working to preserve the Quindaro Ruins. They’d made a good start working to preserve the cemetery, Zane’s father said, but they needed to do the same for the Civil War-era port town.

Zane is the associate director at Freedom’s Frontier, a national heritage area designated by the federal government that includes much of eastern Kansas and western Missouri.

Her great-great grandparents were among the 13 members of the Wyandot tribe who agreed to sell the land so it could be used as an abolitionist town. They operated the Wyandot House Hotel in Quindaro and used some of their property as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Parts of the town, Zane said, was slowly destroyed by a pro-slavery Union general who store his horses in the building and down parts to use for firewood. Many residents moved away. Others, Zane said, left after the state began taxing the Wyandot land.

“Little by little buildings were not kept,” she said.

Over the next century, the town faded away. The construction of Interstate 635 in the 1960s almost certainly demolished historically significant structures. Residents said one two-story stone house still stood only to vanish during construction, according to Larry Hancks, a former city planner for Kansas City, Kansas, and a historian of the Quindaro site.

Hancks wrote in an exhaustive history of the area that no historic studies or attempts at salvage archaeology were made by Kansas at the time. Quindaro’s significance had been “largely forgotten” by that point and “somehow everyone ‘knew’ that the now vanished Quindaro ruins” were confined to an area half a mile west of the highway.

Tai Edwards, a historian at Johnson County Community College, said the decimation of the Quindaro site, and the lack of broad recognition among Kansas City-area residents, has its roots in structural racism in state and federal government.

“The No. 1 reason why this isn’t well known is racism,” Edwards said.

I-635 intentionally obliterated a Black community in Quindaro, she said, adding that federal policy regarding Native Americans also resulted in deliberate erasure of the indigenous history tied to Quindaro.

“There was a lot of flux, I think, amongst the people that were there and policies that target the people that were there and that makes it harder to keep that kind of story that strong because you’ve harmed that community’s identity, it’s notion of itself as a community” she said.

While other elements of Kansas’ pre-Civil War history are broadly known, such as William Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Quindaro’s history is a mystery to many Kansans even as the site has long drawn national and international interest. Edwards said this is in part because Lawrence was not separated and decimated in the same way Quindaro was.

But Quindaro’s history also does not lend itself to the story society likes to tell about the Civil War, she said.

“The way we even teach history is often segregated,” Edwards said. “We don’t teach stories about people who were not very segregated. And Quindaro is a great story about people who were very multicultural.”

After construction of I-635, the state turned over much of the land it had acquired to Kansas City, Kansas, resulting in the city owning much of the townsite alongside the AME Church.

By the early 1980s, the AME Church along with Browning-Ferris Industries, a waste management company, began seeking permission for a landfill on the church’s property. The church’s role in the landfill project has contributed to strained relations within the community to this day.

The proposal was controversial, but the city commission approved a special use permit on a 2-1 vote.

One condition of the permit – Condition E – required an archaeological survey. It began in 1984 and was overseen by archaeologist Larry J. Schmits, who died in 2019.

“Larry started turning up a heck of a lot more than anybody had ever expected to find,” Hancks said in an interview with The Star.

The modern-day effort to preserve Quindaro had begun.

Failed landfill exposed ruins

The landfill proposal illustrates how close the Quindaro Ruins came to permanent erasure – and how early opportunities to secure its preservation were missed, inaugurating the often glacial pace of progress that continues to this day.

The Kansas Legislature in 1988 passed a bill that would have forced the Kansas State Historical Society to take ownership of the land but Republican Gov. Mike Hayden vetoed the policy, arguing it would usurp the society’s traditional process for assuming control of historic sites.

Landfill opponents also successfully gathered 1,000 signatures needed to force the Kansas State Historical Society to consider an application to acquire the Quindaro site. Hancks wrote that while the agency produced a report generally favorable toward acquisition and the Kansas Historic Sites Board of Review had a positive outlook toward the idea, “the project ultimately died because of questions of cost rather than historic significance.”

It was the first – but certainly not the last – time that Quindaro preservation has been thwarted by insufficient funds.

The landfill proposal officially died when the special use permit was canceled after five years had passed without the start of construction. At that point, archaeological work abruptly ended, Hancks wrote, leaving some of the ruins exposed to the elements and further deterioration.

Over the years those working to preserve the ruins have received a handful of federal grants to help with preservation efforts.

In 1993 Kansas City, Kansas, secured a $120,000 grant from the state to stabilize some of the ruins, some of the first public dollars spent on the nascent preservation effort. Work progressed over the next two years, but the excavated ruins were still not backfilled to protect them from the weather because of a lack of funding.

Murray, the economic development advisor, was instrumental in building an overlook that provides visitors with a view of the Quindaro Ruins site. When he originally retired in 2010, one of his colleagues vowed to make even more progress on the site in his absence. But 11 years later, in 2021, Murray came out of retirement and returned to the Unified Government.

Murray said he thought he had left enough money so that, in his absence, the city could begin building out signage in the ruins explaining the area. But he returned, he said, because very little progress had been made on Quindaro and other projects he prioritized.

“I decided, yeah, I need to go back and try to help get those projects kicked off again,” Murray said. He noted that a Kansas City architect, Patti Banks, had developed plans for resolving access issues to the area but that they hadn’t been implemented.

“We thought since Marvin Robinson was elected to the state Legislature that he would latch onto the plan and promote it,” Murray said. “I don’t know if he has but of course he’s run into some other issue that I think the community will overcome.”

Controversy draws attention to site

When $250,000 appeared in the state budget this spring for a strategic plan for Quindaro, it came as a shock to advocates.

The money was included at the request of state Sen. J.R. Claeys, a Salina Republican, who said he was looking for a way to offer Robinson, a freshman legislator, a win after he experienced backlash for voting against the Democratic caucus. Robinson and Republican leadership have denied making a deal for his vote.

Before Robinson gained statewide notoriety as a Democrat voting to support regulations on the lives of trans residents, he was singularly known as an advocate for Quindaro preservation.

Robinson said in an interview with The Star earlier this month that Kelly’s veto of the funding was a continuation of the treatment Quindaro has gotten from those in power for decades. He drew a line from Hayden’s rejection of the 1988 bill to force the historical society to acquire the land and Kelly’s veto last month.

“There are resources available right this second but, you know, it was down to the political will,” Robinson said. “We have to go back and go through institutional violence, economic violence and structural violence where people think it’s OK to just do the least.”

Though $250,000 is the amount Evans, who chairs the Quindaro Ruins Project Foundation, wants for the strategic design, she said Kelly was correct to veto the funding.

No one involved in the Quindaro project was consulted before it was inserted into the budget, she said, and the money would be delivered to the Kansas Historical Society to pick a company for the design rather than directly to the organizations working on preservation.

Evans viewed it as yet another example of money being given to another organization for Quindaro rather than the Black-led groups that have been working on the project for years.

“It was not on a path to get to us,” she said.

Kelly acknowledged a need for more investment in the area, even as she has stood by her veto.

“We need to bring everybody together who has an interest in this and see where it is at this particular point and then see if we can come up with the resources to take care of it,” Kelly told reporters earlier this month.

“It should have been done a long time ago, it should never have been allowed to dilapidate like it has.”

Seeking a unified vision

Evans and other Quindaro advocates hope a strategic plan will provide a unified vision for the future of the site and encourage granting organizations — the groups and agencies with money to offer – to get involved.

Over the years a broad community came to work on the project, including the Wyandot Tribe, the community colleges, the Quindaro Community and the Freedom’s Frontier national heritage project. Evans said she sought to unite them around the idea that the site should be preserved, not developed.

But consistently, Evans said, granting organizations were hesitant to provide funds. She constantly heard critiques that they needed to come together and needed more structured leadership.

Shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic, a board was incorporated with a memorandum of agreement with the Unified Government of Wyandotte County so the organization can begin receiving funds, Evans said. With that, she said, progress is on the horizon.

“I think that they’re seeing that we didn’t need someone to come in and organize us. We’re plenty intelligent enough ourselves to make friends in the community,” Evans said. “But we’re also plenty, not just intelligent, but kind and vulnerable and peaceful to make friends in the community who wanted to come and help us and now we’re getting it done.”

The land itself has many owners and those owners have often had varying viewpoints as to the best path forward. Of the people that have championed the cause over the years, few had expertise in historical preservation and grant writing.

“Most of the organizations aren’t used to handling large monies or reporting on it and don’t have that expertise,” Zane said. “It takes people that have expertise in grant writing.”

One of the primary owners, the AME Church, has also faced distrust from some in the community over their handling of the landfill project and the denomination’s stewardship of the area as a whole. Luther Smith, who runs the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum, said he has long believed it was a mistake for the AME Church to tear down Western University buildings over the course of the 20th century.

“Each one of them should have been like a museum,” Smith said.

Over the years, Murray said, a myriad of plans have been drawn up for Quindaro but time and time again the plans were shelved. Pulling the community together to support the building of the overlook, Murray said, was a “monumental effort” in its own right.

“There’s such passion and interest in the Quindaro Ruins and for some it’s all they have when you look at the northeast community,” he said. “It’s that passion that keeps everyone involved to the extent that people kind of get in the way of each other.”

Evans has also faced concern from some community members because she isn’t from Quindaro, unlike some advocates.

Evans said she felt AME has long been a good steward of the land, and the church is unfairly judged for a singular moment of poor judgment in supporting the landfill plan alongside the Unified Government. But she said it can be challenging for pastors from the church to gain trust in Wyandotte County.

“Wyandotte Countians are very territorial. It’s difficult and hard to become one of them,” Evans said. “That’s one reason why they left me over this project for 14 years. I have no plans to go anywhere until this project is completed.”

Historic recognition could help

Robinson said that progress has been far from linear.

The Democratic representative said the process of waiting for a National Historic Landmark designation has been akin to “waiting for somebody to say we’re gonna go into space and perform open heart surgery in the space shuttle.” Zane said there is an application pending for the designation.

While Congress named the site a National Commemorative Site, the historic landmark designation is determined by the Department of the Interior and guarantees monitoring and technical assistance from the program. Zane said it could be a next step toward national park designation.

Visions for the project include a world-class museum, walking trails through the ruins themselves and signage marking significant places within the ruins. If this can be achieved, Zane said, ripple effects for the Quindaro community will be huge.

“I don’t think it’s enough that we celebrate it, that we have a walking trail,” Zane said. “It also needs to be infused with jobs and money for the community.”

Robinson said he has long viewed the Quindaro preservation as a method to restore a “sense of humanity” to the Quindaro neighborhood, bringing education of a strong history and good paying jobs.

Samuel Lockridge, a longtime resident of Quindaro who runs K.C. Embrace, an organization that promotes community clean ups and Black businesses in Quindaro, said the history of Quindaro presents a prime tourism opportunity for the area. He views it as something Kansas City, Kansas, should capitalize on before tourists flood Kansas City for the World Cup in 2025.

“(Quindaro) deserves to finally live up to its history and what it was,” he said.

The battle continues

More investment in Quindaro may be right around the corner. Kelly’s veto of the $250,000 in funding was disheartening to some community members, but it has drawn more attention to the site than it’s had in recent memory.

GOP lawmakers who were critical of Kelly’s veto have pledged to ensure Quindaro gets funding in the future – effectively locking themselves into supporting a project that has previously failed to gain legislative traction.

U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, a Missouri Democrat who represents Kansas City, said he plans to advocate for earmarks or a special grant from the Department of the Interior for the project.

“We’ve got a political situation over in Kansas where a lot of the African Americans are upset with an African American legislator. So that’s making it a little more difficult,” said Cleaver, a member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

If Quindaro receives money and resources, Edwards said, she doesn’t care what political controversy caused it.

“It is not new for Quindaro to be used as a political tool,” she said. The site, its founding, and its history, she said, are inherently political.

For decades preservation advocates have been trying to keep faith, hopeful that eventually a moment will arrive when politics and the nation’s desire for a richer understanding of Black and indigenous history converge to elevate Quindaro to the rightful place in the country’s consciousness they believe it deserves. They believe that time is finally coming.

At the Quindaro overlook, dedicated on Juneteenth 2008, a plaque nods to that long history: “The battle continues in our quest to save and preserve more of the ruins.”

The Star’s Daniel Desrochers contributed to this report.