Oklahoma readies for 25 executions in 2 years. But critics ask, 'Why the rush?'

Beginning Thursday, Oklahoma is set to execute its first of more than two dozen death row inmates over the next 29 months — an average of one execution per month over the next two years. If carried out in full, the unprecedented number of 25 executions would put to death 58% of the state’s death row inmates, who include a flurry of incarcerated individuals with mental health disorders and others who have maintained their innocence.

Given the state’s complicated history with executions, which includes botched procedures and a number of exonerations of death row inmates, legal experts and critics alike are perplexed by its fervor to kill so many people in such a short amount of time.

“Why the rush to execute 25 people?” Tracy Hresko Pearl, a professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Law, queried in an interview with Yahoo News, calling 25 executions in two years “horrifying.”

James Coddington was the first inmate to be executed and died on Thursday morning. Coddington, who had been in jail since 1997 for killing a friend who refused to loan him $50 to buy cocaine, was denied clemency by Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt on Wednesday, despite the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommending him for clemency earlier this month. Coddington repeatedly expressed remorse for the murder, and his lawyers said he had worked to turn his life around for the better behind bars — all to no avail.

“Oklahoma views its criminal justice system as, No. 1, infallible and, No. 2, punitive, above all else,” Pearl said. “I think that the advent of DNA evidence has really shown us how often we get cases, and even very serious capital cases, wrong.”

In fact, according to the 2019 annual report by the National Registry of Exonerations, somewhere between 2% and 10% of all convicted individuals in U.S. prisons are innocent — a stat that many legal experts argue is far too high to legitimize capital punishment for anyone. Another report by the registry in 2020 found that more than half of the wrongful criminal convictions are caused by government misconduct, which rarely faces consequences.

“Misconduct by police, prosecutors and other law enforcement officials is a regular problem and it produces a steady stream of convictions of innocent people,” Samuel R. Gross, an emeritus professor at the University of Michigan Law School and a co-founder of the registry, told the Washington Post.

It’s an ugly truth that many have paid for with their life, while others have paid financially.

State capital cases, or death penalty proceedings, cost state taxpayers 3.2 times more than non-capital cases on average, according to a 2017 study of the Oklahoma death penalty. More revealing, an analysis of 15 death penalty cases nationwide, from that same study, determined that seeking the death penalty results in an average of approximately $700,000 more in costs than not seeking death.

Complicating the death penalty’s implementation, certified physicians are barred from participating in the practice. The American Medical Association in 2006 announced that any physician who participates in an execution violates their Hippocratic oath to protect lives. As a result, the state goes to extreme lengths to administer executions. Earlier this year it was revealed that Oklahoma paid a doctor $15,000 per execution (to check consciousness, verify the drugs being used and ultimately confirm death), plus another $1,000 a day for training. The high financial burden, coupled with various moral and efficacy dilemmas associated with state-sanctioned executions, presents a serious cause for concern for many critics.

“My hope is always that the state views the goal of its criminal justice system to be truth above all else,” Pearl said. “And I think that when a state rushes to execute a large number of people, what it’s doing is something very different than pursuing truth. It’s pursuing punishment above all else. And I think that should be incredibly disturbing for all Americans.”

Another concern for legal experts is transparency around where the ingredients that make up lethal injections for Oklahoma executions come from, something they say has always been shrouded in secrecy. Readily available information online details a three-drug method, which is the current protocol in at least 23 states: a barbiturate that acts as a sedative and painkiller, a drug that causes paralysis such as vecuronium bromide and a dose of potassium chloride to stop the heart.

No information about where the drugs are obtained or their efficacy is publicly available. The Oklahoma Department of Corrections, which is in charge of carrying out the executions, did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Yahoo News.

Andrea Digilio Miller, legal director of the Oklahoma Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to finding and resolving wrongful conviction cases in the state based at the Oklahoma City University School of Law, believes more transparency in the entire execution process would allow Americans to have more informed views on the death penalty. In its absence, she says, many are left to think the worst.

“Who are we getting our [lethal injection] drugs from?” Miller probed in an interview with Yahoo News. “If these aren’t drugs that are really available on the open market, where are they coming from? And are they expired? I think those are the sorts of things that people should know so that it can inform their individual beliefs about the death penalty.”

Having spent more than two decades as a public defender in Oklahoma, Miller has at least six former clients who are on the list of 25 death row inmates slated to be executed in the next two years. Among those names was Coddington.

For Miller, given Oklahoma’s deeply conservative values, which are anti-abortion and include having the strictest abortion ban in the country, the championing of the death penalty seems to go directly against the basic idea of preservation of life.

“We in this country talk so much about trying to protect children while they’re children, but then for the children who slipped in the cracks and the system doesn’t help, we’re more than willing to throw them away on the back end when they make a mistake,” she said. “And that’s very much what the James Coddington story is.”

“He came from abject poverty. He came from a very abusive background and a background where everybody in his life had substance abuse problems,” she added. “And every death row inmate I have ever represented suffered from the consequences of that type of trauma.”

In spite of advocates’ best efforts to delegitimize the death penalty in Oklahoma, the reality is that executions have been the law of the land in the state for more than two centuries. Capital punishment was first introduced there in 1804 when Congress made criminal laws in the U.S. applicable to lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, which include present-day Oklahoma. At the time, only “willful murder” was punishable by the death penalty. Since then, Congress has expanded the scope to include several other offenses, including treason, espionage and rape.

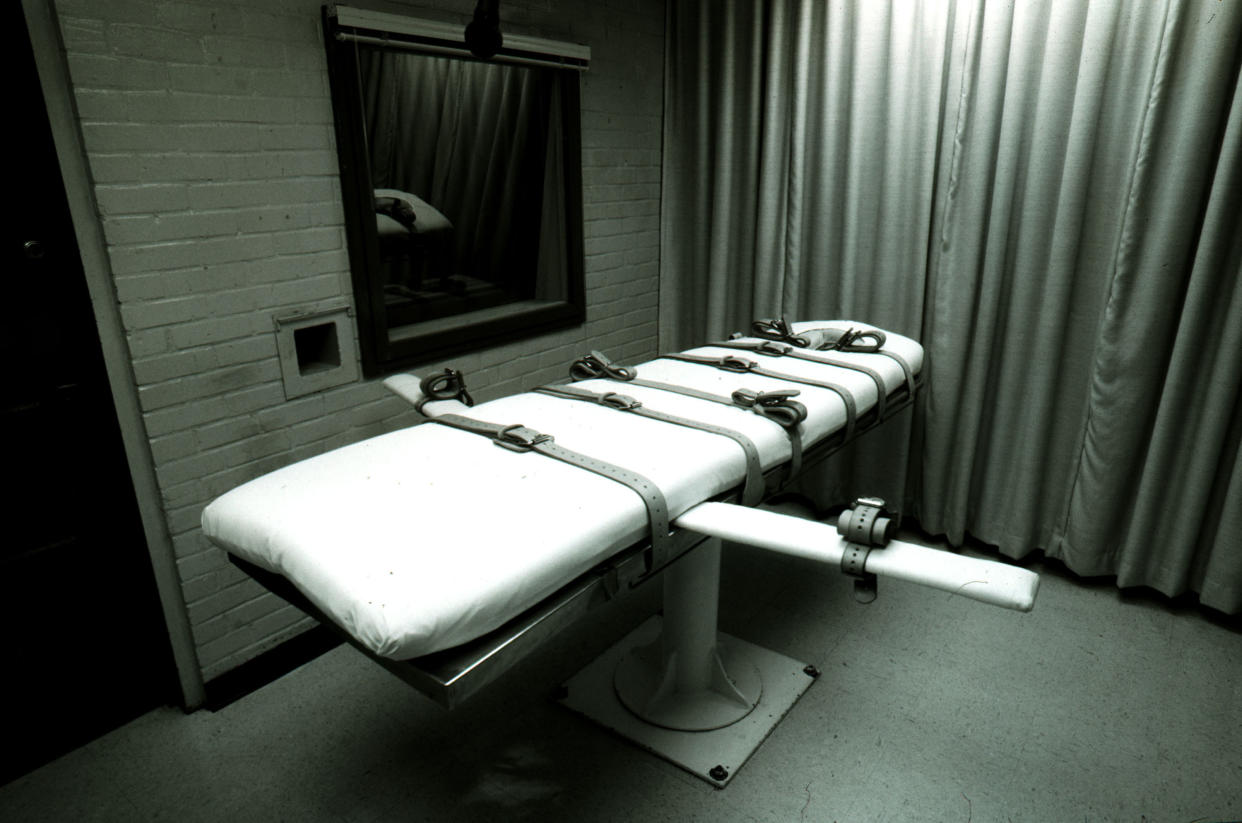

The original death penalty law called for executions to be carried out by electric chair, but the Supreme Court deemed that unconstitutional in 1972. The current death penalty law, enacted in 1977, calls for executions to be carried out by lethal injection. From 1915 to 2022, Oklahoma has executed a total of 196 men and three women, according to the state’s own records.

But they haven’t all gone as planned.

In 2014, Oklahoma death row inmate Clayton Lockett squirmed and moaned for more than 40 minutes during his execution before suffering a heart attack. Just months later, another inmate, Charles Warner, complained, “My body is on fire,” according to witnesses, as he was killed. Then just last year, inmate John Grant, vomited and convulsed as he lay on the gurney before he died, drawing sharp criticism for the practice.

Richard Glossip, one of the 25 death row inmates scheduled to be executed, will likely eat his fourth last meal on death row. In 2015, just as he was set to be injected with the lethal cocktail, officials realized they had the wrong drug, sparing his life. Having always claimed innocence for a killing he was accused of, Glossip is hoping a last-minute appeal works in his favor.

Instead of Oklahoma leadership slowing down executions as numerous issues arise, the process and quantity are just picking up.

“Oklahoma did not execute anyone for over 6 years and 9 months, from mid-January of 2015 until late October of 2021,” Maria T. Kolar, an assistant professor of law at Oklahoma City University School of Law who teaches courses about criminal law and capital punishment, told Yahoo News in an email. “In an era when executions are at a new low nationwide for the modern era — for so many reasons — it seems reasonable to ask whether Oklahoma really wants to ‘lead the nation’ when it comes to executions.”