Former NFL star Michael Vick owes us $1.2 million, creditors say in South Florida lawsuit

After spending nearly two years in prison, ex-NFL quarterback legend Michael Vick rehabbed his image, resumed his storied playing career and became a TV broadcaster. Vick and his wife now live in a newly built house in South Florida.

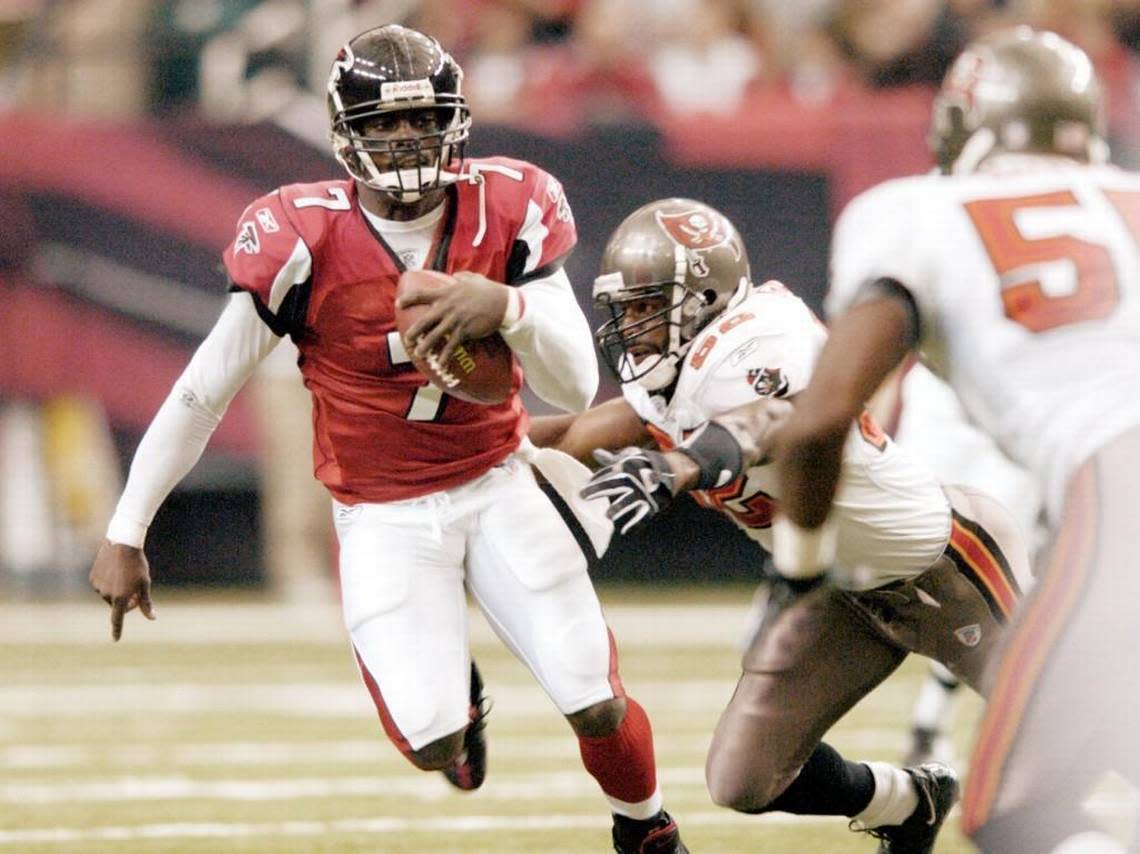

But Vick, who electrified fans by outrunning defenders, can’t seem to shake off financial trouble.

A group of creditors has gone to Broward County circuit court to force the former Virginia Tech and pro quarterback to pay about $1.2 million in judgments stemming from loans he received in Maryland in 2018 — the latest in a long string of debts he’s wracked up over the years.

Lawyers for the group, which purchased Vick’s debt, have now issued subpoenas for the Vicks, hoping to have them detail their assets in depositions scheduled for Aug. 5. The group can’t go after the Vicks’ new Southwest Ranches house because under Florida law, the property is protected as the couple’s primary residence. But the plaintiffs are hoping to demand other assets such as cars, jewelry and even sports memorabilia.

“They are indeed living in the house. There was a $160,000 Bentley in the driveway,” said Kevin Spinozza, a Coral Gables lawyer spearheading the local effort to collect. “Obviously a beautiful home, one you would think a retired NFL player would live in.”

Vick, 42, who recently landed a job with an athlete management firm, Level Sports Group, could not be reached for comment.

His South Florida lawyer, Arthur Jones, in a statement suggested that the amount of money of the judgments was inflated.

“Michael Vick takes these matters seriously and is aware of the proceedings and will be sure that all parties who are entitled to receive payment will be paid,” he said. “However, usurious calculations which produce absurd results should not be countenanced by the courts of Florida. Therefore, all appropriate defenses will certainly be utilized. Further comment on any shenanigans which lead to situations like this may be made available at a later date.”

Long-running financial woes

The former Virginia Tech and Atlanta Falcons star saw his football career derailed when he pleaded guilty and went to prison in 2007 for his role in running an illegal dog-fighting ring. Two years later, he walked out of prison and went on to largely rehabilitate his image while playing with the Philadelphia Eagles. He also filed for bankruptcy, listing $17 million in debt.

But in recent years, as Vick ventured into NFL sports analysis with Fox, he’s been dogged by debt involving an unusual web of loan companies and individual investors.

Notably, he received $400,000 in loans in 2018 through a Bethesda, Maryland, company called Atlantic Solutions. According to The Washington Post, Atlantic Solutions was the middleman for an Oregon company called NV Partners, which hoped to sign up current and former athletes who needed immediate cash, in exchange for future earnings.

Vick was supposed to pay back the money through future earnings on his TV and coaching gigs, but never did, NV Partners claimed in court documents. He was eventually slapped with a $1.9 million judgment. NV partners hasn’t collected a dime — and the amount owed has increased because of interest, said Daniel Wright, the company’s lawyer.

“This man has paid nothing,” Wright told the Herald.

But the latest judgment stems from two completely separate loans, also with Atlantic. The money was to be paid back by the sale of the Vicks’ former home in Broward County and “funds from Mr. Vick’s retirement and pension accounts with the National Football League,” according to the suit filed in Maryland.

That debt was eventually sold to a broker company called SMA Hub, which divvied up interest in the loans and sold them to six different people: Li Xu and Hong Jiang, of Kernsersville, North Carolina; Lorraine Wood, of Aston, Pennsylvania; Rajeh and Sangita Garg, of Naperville, Illinois; and Sandra Pierce, of Pflugerville, Texas.

‘I’m in a pickle’

Pierce, a 60-year-old grandmother, is a teacher’s assistant in the town outside Austin. Through a co-worker’s investment manager, she learned about the broker company’s “NFL tax-qualified annuity program.”

She poured in her $50,000 life savings, thinking it was a better investment than, say, a 401(k) that depended on the stock market. In all, the return on the investment was to be about 5.5 percent over six years.

“I thought annuities were rock solid,” she said in an interview. “I would get a nice chunk every May 1, for six years. The risk wouldn’t be there.”

But Vick never paid. Pierce, who had hoped to retire next year, is now struggling to make ends meet — her savings are gone, and she was forced recently to take a four-month leave from work because of a flare-up with her multiple sclerosis.

“I’m hoping the Vicks will do the right thing and pay,” Pierce said. “I want to have security and breathe easier. I don’t want to have to sell my house. I’m in a pickle right now.”

After none of the payments were made to the creditors, a court in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, issued the judgments against Vick in March.

The group is “just the latest people who Mr. Vick has stiffed,” according to the Maryland lawsuit filed by Baltimore attorneys Kevin Docherty and Andrew Freeman.

With Vick living in Broward — and no payments having been made — lawyers for the six filed suit in Broward to enforce the judgment.

Vick’s faced legal actions in Broward before. In 2017, he was sued by CBS Radio East for breaching a contract by failing to regularly appear on the New York City radio station WFAN during the 2014-2015 season. The suit sought the return of $9,000, and later settled.

That same year, a financial arm of Mercedes-Benz sued Vick because he’d stopped making payments on a car he purchased. He eventually paid over $26,000 to satisfy the debt, records show.