NC railroad cop murdered 100 years ago gets name on national memorial in DC

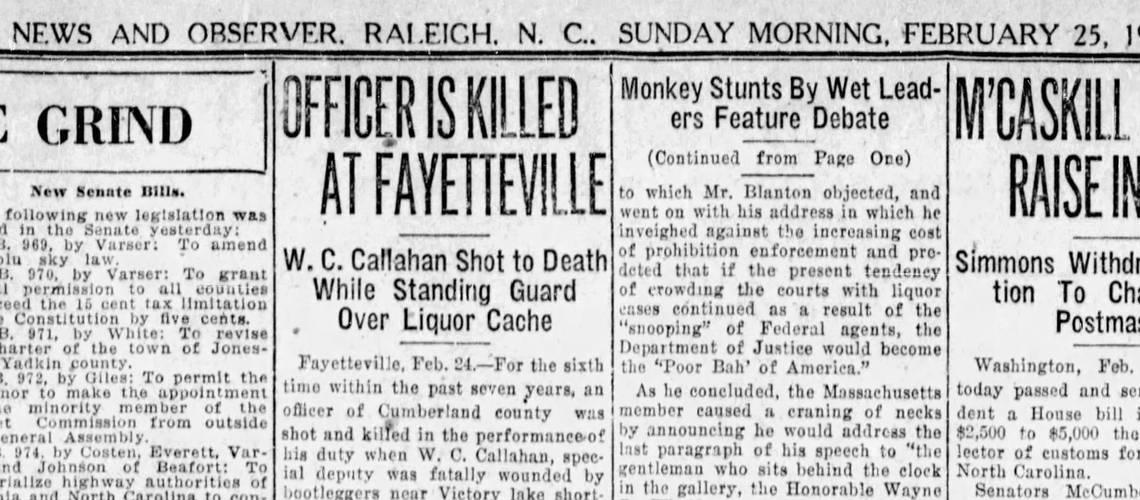

In 1923, William “Bunk” Callihan stumbled on a pair of bootleggers stashing whiskey jars in the woods, and when the Fayetteville lawman seized the liquor and placed the men under arrest, he caught a bullet through the back — fatally piercing his kidney.

He was just 43 when the gunshot took him, an officer both for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and the Cumberland County sheriff, and the tangled story of his murder remains unsolved after a century.

What is certain: The man sent to prison for Callihan’s murder didn’t shoot him. What is almost certain: The 1920s justice system framed a bystander for the crime of being Native American, though Callihan himself named a different killer on his deathbed.

But these failings aside, Callihan received a slain officer’s due one century late on Saturday when his name got added to the National Law Enforcement Memorial in Washington, D.C., rescued from the obscurity of newspaper archives.

A volunteer with the Wilmington Railroad Museum brushed the dust off Callihan’s story, tracked down his granddaughter in Fayetteville, alerted the monument authorities and even corrected the engravers on the spelling — Callihan not Callahan.

And on Saturday night, Barbara Capps stood at the candlelight vigil four blocks from the U.S. Capitol, saluting the grandfather she never met.

“He was just a very conscientious man,” she said. “Liked his job, put 100% into his job. I think it’s an awesome honor after all this time. Kind of wish it had happened before my daddy passed away.”

The Wilmington museum offers a whole exhibit to railroad officers, who in Callihan’s day would have tossed freeloaders out of boxcars and foiled would-be stick-ups in the passenger cars. But they also guarded the rail yards, and that’s likely how Callihan would have spent his time, standing watch over cars that sat idle outside Fayetteville.

Christine Williams volunteers at that museum, and while redoing a display case, she discovered a list of fallen railroad officers didn’t match up with the list at the national memorial. A retired officer herself, splitting time between Wilmington and her home in Wisconsin, she set about bringing Callihan’s name into the 21st century.

“It’s one of the coolest things I’ve done,” she said. “It’s 100 years in the making, to have this happen.”

The story of Callihan’s end unfolds almost entirely in 100-year-old newspaper accounts, which differ wildly not only in facts but also by spelling of proper names. But you can hear the frustration come screaming through the linotype as my long-gone N&O colleague banged out this dispatch:

“Considerable secrecy has marked the investigation of Callahan’s death, and when this correspondent learned that Levy has been taken into custody, much questioning was necessary.”

The Levy mentioned here would be Joel Levy, who was arrested and quickly tried for the lawman’s shooting. News accounts describe him as a “Negro” and a “Croatan,” but Levy would almost certainly identify as Lumbee were he alive today.

Who killed Callihan?

All versions of this story more or less agree that Callihan and two other men were out behind a textile mill south of Fayetteville, looking for kindling to start a fire, when a car drove up and two men got out without seeing the lawman. They dumped four bags and drove away, and when Callihan looked inside the sacks, he found bountiful jars full of moonshine and promptly ordered his two companions to alert the sheriff while he stood guard.

Stories start to vary at this point, but it seems clear that two men soon returned for the stash of illegal booze: Levy and John Smith, a known moonshiner from nearby Gray’s Creek. One of Callihan’s men said he couldn’t tell who did the shooting. But the other, one B.F. Strickland, told investigators that “the Croatan” fired.

This landed Levy behind bars.

His trial began only weeks later, but it quickly turned sensational when Ethel Andrews, a nurse at Highsmith Hospital, testified that the dying man implicated Smith with some of his final words. No less a figure than A.B. De Mesquita, publisher of the Fayetteville Observer, testified that the nurse told him this same story while he was his patient.

A century later, Barbara Capps can remember her grandmother insisting the same thing:

“He told my grandma, ‘Levy didn’t shoot me. He was standing in front of me. I was shot in the back,’ “ she said.

Not surprisingly, justice did not exactly prevail.

A jury deadlocked 8-4, but even after the judge declared a mistrial, Levy remained jailed on a $10,000 bond — about $177,000 in today’s money. Smith did get arrested, but when all was said and done, he served six months on a road gang for his bootlegging.

Levy, however, faced a second trial only eight months after Callihan’s death. And this time, a freshly married Ethel Andrews Wise had moved to Florida, where she could not be reached. De Mesquita had died in a plane crash. Transcripts of their earlier testimony had strangely gone missing.

Facing murder charges for a second time, Levy testified he never heard about Callihan’s shooting until a Fayetteville police officer asked him about it shortly afterward. His defense team produced six alibi witnesses, including the Fayetteville officer and a “prominent Negro physician.” They also lined up three witnesses to say that the other man with Callihan that day, one B.W. Hall, all told them that Smith pulled the trigger.

The prosecution called only two witnesses, Strickland and Smith himself, who testified that he hollered “Don’t shoot!” at the crucial moment. For good measure, he added that he had been recently saved at a traveling revival.

But while Levy found himself convicted and sentenced to a minimum of 20 years, he got paroled after only three. This, more than any of the obviously trumped-up facts, suggests some serious legal shenanigans. Little else explains how a convicted police-killer, and a Native American in the 1920s, could serve such drastically shortened time.

Williams wants to seek an official pardon for him, and she would appreciate any help doing so. Regardless, there is no further mention of Levy beyond 1926 other than he “went North.”

“It may have been an agreement that he get out of here and never talk about it again,” said Holli Saperstein, railroad museum director in Wilmington. “We don’t know. It feels that way.”

Regardless, the officer who died young without meeting his granddaughter has a new legacy beyond that moonshine still in the woods.

And this one is chiseled in stone.