Will McCarthy, Jordan talk to the Jan. 6 committee? Panel faces dilemma in coaxing defiant GOP

WASHINGTON – With hearings a month away, the House committee investigating the Jan. 6 Capitol attack wants to question six Republican lawmakers about their conversations with former President Donald Trump and – for some – their knowledge of the protesters who laid siege to the building.

But given the tight time frame, the committee might not get the answers it wants.

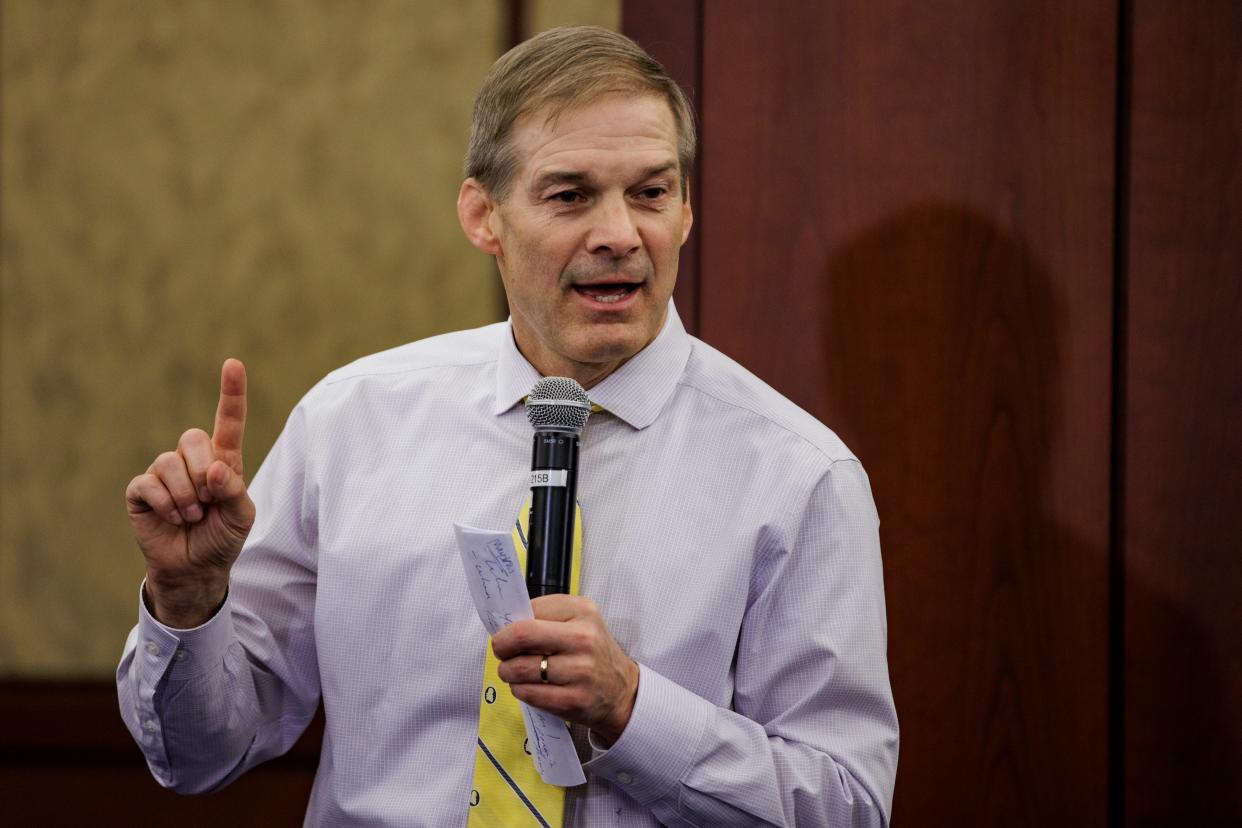

Each of the lawmakers – House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California and Reps. Jim Jordan of Ohio, Scott Perry of Pennsylvania, Andy Biggs of Arizona, Mo Brooks of Alabama and Ronny Jackson of Texas – have refused to cooperate with an inquiry they criticized as illegitimate and partisan.

The committee could respond to the defiance with the aggressive step of subpoenaing fellow House members. But if lawmakers fight the subpoenas, which at least Brooks vowed to do, the House could be faced with an unpalatable choice between lengthy court battles or a rarely used procedure to jail its own members.

Police arrested in Jan. 6: 'Elephant in the room': Police grapple with charges against officers Capitol attack

“The goal here strategically is delay and frustrate, not win on the legal merits,” Kimberly Wehle, a law professor at the University of Baltimore, said of defiant lawmakers.

Committee members say they want to ask the Republican lawmakers for more details – or responses to allegations – they’ve heard from more than 800 witnesses who cooperated with the inquiry, including more than a dozen former White House staffers. The allegations include lawmakers encouraging Trump to contest the election results and recruiting protesters before the attack.

The panel's goal is to create a minute-by-minute account of what happened as a mob of Trump supporters ransacked the Capitol, injuring about 140 police officers and temporarily halting the count of Electoral College votes certifying President Joe Biden’s victory.

But the lack of cooperation from some lawmakers could leave gaps in the record. The ultimate risk from the clash over evidence is the results could be viewed as partisan, rather than an unbiased report modeled on the commission that studied the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Jan. 6 committee aims for June hearings: Will they affect the 2022 elections?

“The committee wants to give every opportunity to people to come forward with information relevant to the investigation,” said Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., one of the committee members. “We feel that’s true regardless of your political party or title or job. We want everybody to come in. What that means in a particular case remains to be seen.”

What does the Jan. 6 committee want to ask Biggs, Brooks and Jackson?

The committee developed questions for Republican lawmakers during nearly a year of accumulating other evidence, including texts the committee received from former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows. Recent news reports revealed more details about what led to the attack and what happened that day.

Brooks spoke at Trump’s rally Jan. 6 before the mob attacked the Capitol. But after Trump endorsed a Republican rival in the Alabama Senate race, Brooks said on a local television program that Trump “asked me to rescind the election of 2020." Brooks said in a press release Trump wanted him to "immediately remove Joe Biden from office."

The committee wants to ask Brooks about his conversations with Trump. But Brooks, who said he advised Trump neither the Constitution nor federal law permit what he sought, said the committee would “have to send me a subpoena, which I will fight.”

Secret Service worries: Ex-officials worried by troubling Secret Service case as agency struggles with hiring, training

The committee has question for Biggs about attending White House meetings, including on Dec. 21, 2020, and planning Jan. 6. The plans, based on testimony from others the committee said it obtained, included a discussion of Vice President Mike Pence rejecting electoral votes from certain states, which a federal judge ruled “more likely than not” meant Trump corruptly tried to obstruct Congress.

The committee wants to question Jackson, a former White House doctor for Trump, about a series of texts Jan. 6 with him as the subject among Oath Keepers, a far-right group whose members are charged with seditious conspiracy. One message said, “Hopefully they can help Dr. Jackson” and another said, “He has critical data to protect.”

Jackson denied knowing or having contact with the Oath Keepers.

Drinking, a fence-jumper, party-crashers: How scandals have dogged the Secret Service for years

The committee renewed its request to question McCarthy about his conversations with Trump after the New York Times reported the Republican leader saying Trump should have resigned and “bears responsibility for his words and actions.” The panel still wants to hear from Jordan about conversations he had with Trump and text messages to Meadows. Perry's texts and other communications he had with Meadows are an interest of the committee.

3 more lawmakers asked to testify: Jan. 6 committee calls Republican Reps. Andy Biggs, Mo Brooks and Ronny Jackson to testify

Can the panel subpoena lawmakers? Likely. But doing so presents other issues.

The committee plans eight hearings in June and a fall report, in order to finish before the Nov. 8 election. The panel hasn't yet decided whether to subpoena lawmakers, Trump or Pence to bolster what they know.

A committee member, Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., told CBS’s “Face the Nation” on Sunday the committee would issue subpoenas strategically based on the type of information sought and whether it could be obtained in time.

“I think ultimately, whatever we can do to get that information, I think if that takes a subpoena, it takes a subpoena,” Kinzinger said.

The committee chairman, Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., told NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Jan. 2 the authority wasn’t clear cut.

“Well, I think there are some questions of whether we have the authority to do it,” Thompson said. “We're looking at it. If the authorities are there, there'll be no reluctance on our part.”

Legal experts say Congress clearly has the authority to subpoena its own members. But fighting to enforce the subpoenas could take longer or require divisive political votes.

Trump documents: What documents does Trump not want the Jan. 6 House panel to see? Appointments, call logs and handwritten notes

“To say somehow these subpoenas are not within the scope of the investigation is a silly argument," said Wehle, the law professor. “They can’t legislate in a vacuum."

Irvin Nathan, a former House counsel, said subpoenas were issued for Oregon GOP Sen. Bob Packwood’s diaries and New York Democratic Rep. Charlie Rangel’s financial records during congressional ethics investigations. But those lawmakers didn't challenge their subpoenas.

Another factor is political. House Democrats might be reluctant to pursue subpoenas because Republicans could wield the same power if they regain control of the chamber after the November elections, Nathan said.

“It obviously has to have the power to compel testimony from members,” Nathan said of the House. “The question is whether it has the political will to do it.”

A lawsuit, a criminal charge or jail

The House has three options to enforce a subpoena: a civil lawsuit, a criminal charge or jail. Each method has its drawbacks.

The committee could file a civil lawsuit asking a federal court to compel the testimony. Federal courts have upheld the committee's legitimacy and the Supreme Court refused to prevent the release of Trump administration documents.

But civil lawsuits can take months or years – longer than the committee's goal of finishing by fall.

More: Trump investigations set to accelerate in coming weeks: Where the inquiries stand

Another option is for the Justice Department to press criminal contempt charges. The department has charged Trump political strategist Steve Bannon and a trial is scheduled July 18.

But the department hasn't yet decided whether to press charges, as the House urged, against former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, former trade adviser Peter Navarro or former deputy chief of staff Dan Scavino.

The inaction has frustrated committee members, who urged Attorney General Merrick Garland to take action.

“The Department of Justice must act swiftly,” Rep. Elaine Luria, D-Va., said at a March committee meeting. “Attorney General Garland, do your job so that we can do ours.”

A third, rarely used option is for the House to jail its own members. The House could ask the Sergeant at Arms to jail a defiant lawmaker under a procedure called inherent contempt.

From 1795 to 1857, the House and Senate initiated 14 inherent contempt actions and meted out punishment in eight cases, according to the Congressional Research Service. But the process was eclipsed in 1857 when Congress enacted a criminal contempt statute.

Raskin, who taught constitutional law for 25 years before becoming a lawmaker, said in in October the House could revive inherent contempt to enforce its subpoenas. "No one in the United States of America has the right to blow off a subpoena by the United States Congress," he told reporters.

Rather than jailing members, Nathan said under inherent contempt the House could rescind committee assignments or salaries for defiant lawmakers. The punishment might compel faster results than waiting for civil or criminal courts to rule, he said.

"Under inherent contempt, they could reverse the dynamics,” Nathan said.

Nathan and Wehle each argued that Congress should assert its subpoena power more forcefully because otherwise a president could simply ignore lawmakers.

“It’s less a question of 'Is it legal?' and more of a question of 'What happens in the breach?'” Wehle said. “If people refuse to comply and things get tied up in the courts, then what happens to the subpoena power?”

More: Ex-president in the crosshairs: Jan. 6 committee puts Trump on notice as US marks riot anniversary

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Jan. 6 committee quest to grill McCarthy, Republicans faces dilemma