Law aimed at doctors who spread COVID-19 misinformation is put on hold by judge

A federal judge in California has temporarily blocked the enforcement of AB 2098, a weeks-old state law intended to halt the spread of lies and misinformation surrounding COVID-19.

Judge William Shubb of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California granted the preliminary injunction Wednesday in two related cases that challenged the law's constitutionality.

In December, Judge Fred W. Slaughter of the U.S. District Court for California’s Central District denied a similar motion in a separate lawsuit aimed at the bill.

Also on Wednesday, the 9th Circuit agreed to hear the appeal for that case alongside a fourth, similar lawsuit filed in California’s Southern District.

“We can all agree that if doctors are spreading COVID misinformation deliberately, that’s a problem,” said Hannah Kieschnick, a staff attorney for the ACLU of Northern California, which filed amicus briefs in all four lawsuits. "We want the government to be able to protect the public from unsafe treatments and unsafe doctors."

But AB 2098, she said, “is unconstitutional, unnecessary and risks pretty severe unintended consequences.”

Assemblyman Evan Low (D-Campbell) introduced AB 2098 in February to grant the Medical Board of California the ability to discipline doctors who spread false information about COVID-19 for unprofessional conduct.

In its original version, the bill spelled out the kinds of actions that could result in discipline under the new law. The board would have to consider, for example, if the misinformation in question “was contradicted by contemporary scientific consensus to an extent where its dissemination constitutes gross negligence,” and if the doctor’s actions resulted in their patient “declining opportunities for COVID-19 prevention or treatment that was not justified by the individual’s medical history or condition.”

By the time it reached Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk in September after several rounds of amendments, the bill’s language was much more vague.

In his signing statement, Newsom acknowledged that he was “concerned about the chilling effect” of legislating doctor-patient conversations.

But this law, he wrote, “is narrowly tailored to apply only to those egregious instances in which a licensee is acting with malicious intent or clearly deviating from the required standard of care while interacting directly with a patient under their care.”

The final version of the law doesn’t actually spell out any of those egregious cases or specify how the board would define malicious intent. Shubb ruled that the law’s “unclear phrasing and structure” could have a “chilling effect.”

“As it stands, doctors reading the statute have no assurance that the statute will be interpreted by courts or applied by the boards consistently with the defendants’ proposed interpretation,” the judge wrote.

Some sections of the law are written in a way that makes clear interpretation nearly impossible. The final text defines misinformation as “false information that is contradicted by contemporary scientific consensus contrary to the standard of care.”

“Put simply, this provision is grammatically incoherent,” Shubb wrote. “It is impossible to parse the sentence and understand the relationship between the two clauses.”

Dr. Donaldo M. Hernandez, president of the California Medical Assn., said he was “disappointed” in the ruling.

“There has been a lot of false rhetoric about what this bill does,” Hernandez said in a statement. “AB 2098 applies only when a physician intentionally misleads a patient under their care or deviates from the appropriate standard of care. It does not stifle legitimate, needed and appropriate scientific and medical debate. We cannot let the toxicity of the moment blind us to the moral and ethical obligations physicians have to our patients.”

Opponents of the law say its wording does not sufficiently protect legitimate medical care.

“The problem with AB 2098 is that it’s so broad that it’s going to chill the speech of well-meaning doctors who are providing even accurate, appropriately tailored care,” Kieschnick said. “The Legislature went too far. And they didn’t need to.”

State law already bars doctors from lying to their patients or dispensing shoddy medical advice that fails to meet the basic standard for quality care. That's the case for all diseases, including COVID-19.

AB 2098 applies only to conversations between patients and their doctors about the patient’s care. It does not apply to statements that a person with a medical degree might make in public settings, such as social media posts, rallies or talk show appearances.

A legislative analysis of the bill before its passage found that any attempt to limit doctors’ public statements would probably not survive a 1st Amendment challenge in court.

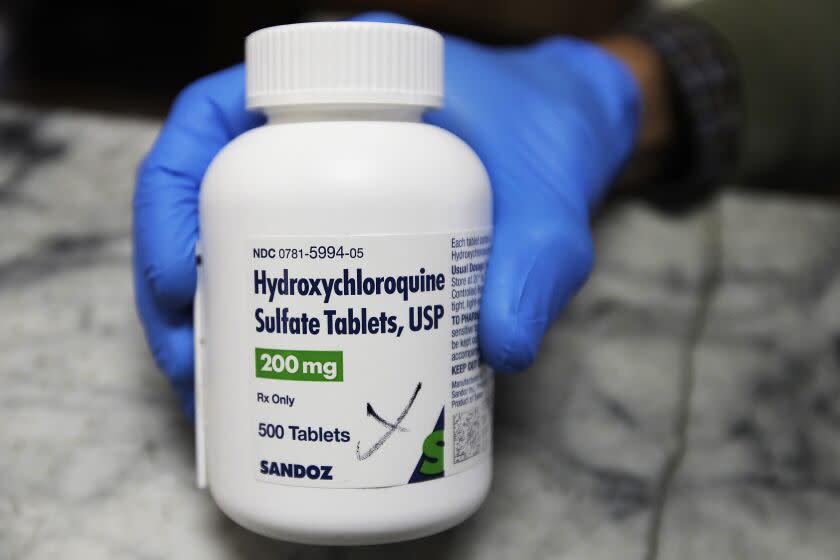

Plaintiffs in the various lawsuits against AB 2098 include Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit peddler of inaccurate health information founded by vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and a Newport Beach doctor who has promoted the use of discredited COVID-19 treatments ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.

Not all of the bill’s opponents embrace misinformation. They just don't embrace this particular law.

“When somebody says the COVID vaccines have microchips in them, that the COVID vaccines have the sign of the devil in them, that’s clearly an issue that we need to address,” said Dr. Eric Widera, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco who specializes in geriatrics. “I very much am for addressing misinformation. I just don’t think this bill does it.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.