These kids went to a Fort Worth clinic for help. Instead, some suffered abuse, trauma

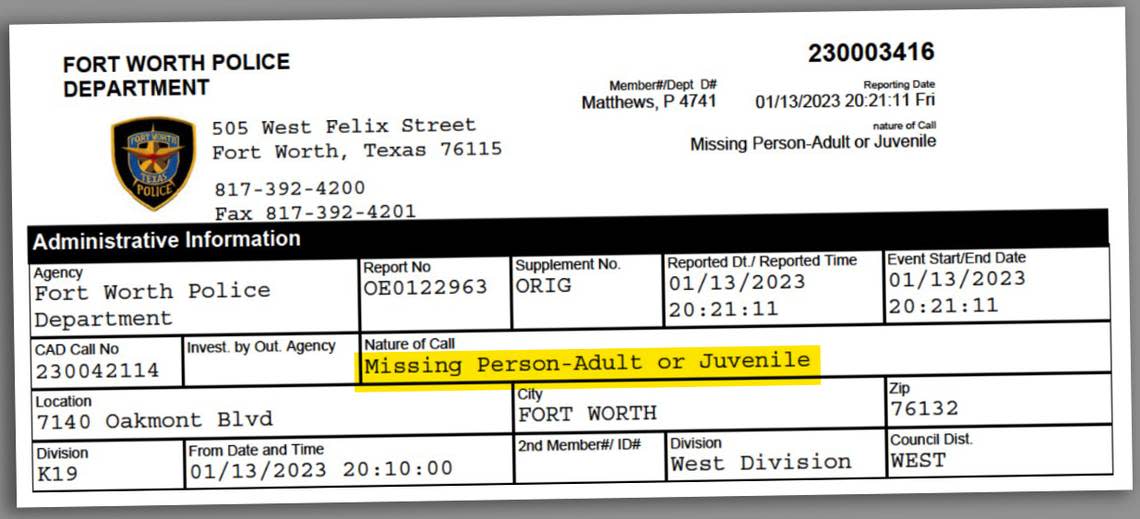

It was after dark when a teenage girl in foster care ran away from Fort Behavioral Health for the second time in less than 48 hours.

The staff at the residential treatment center, where the girl was staying, followed her as far as they could before calling 911 on that night in January.

“She was recently sex trafficked,” a staff member told a 911 dispatcher, “and had a court date and all that to put people in jail, so we’re just really worried.”

The girl returned to the center less than two hours later. But for Fort Behavioral, it wasn’t a happy ending.

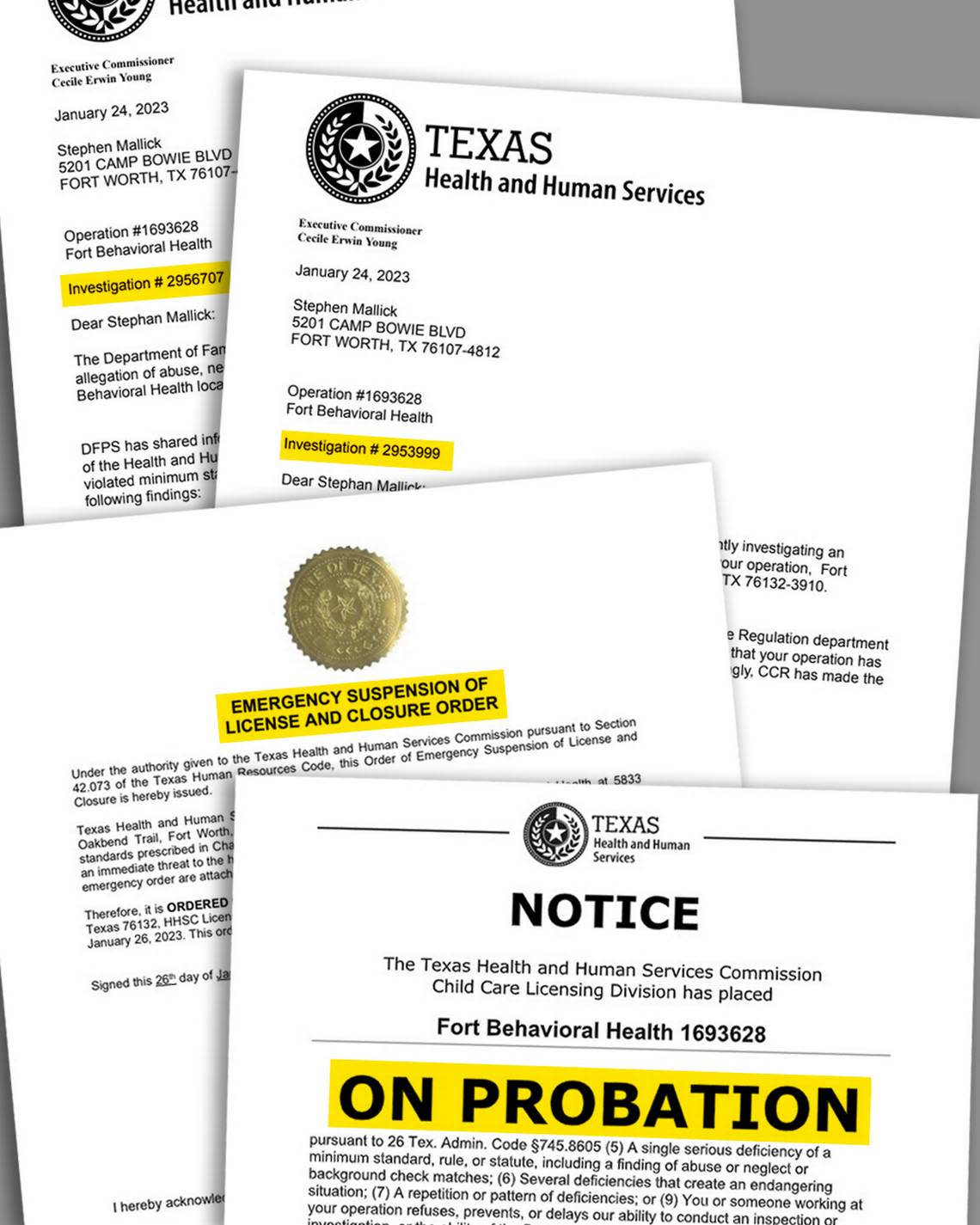

Four days later, the state of Texas pulled all the foster children out of the facility. And nine days after that, regulators took the drastic action of shutting down Fort Behavioral for 30 days, sending home the other children being treated there.

The closure, which left parents scrambling to find alternative treatment, was triggered by “an immediate threat” to children in care, the state said at the time. Regulators with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission have never explained to parents or the public what that threat was, and the facility was allowed to reopen on probation after 30 days.

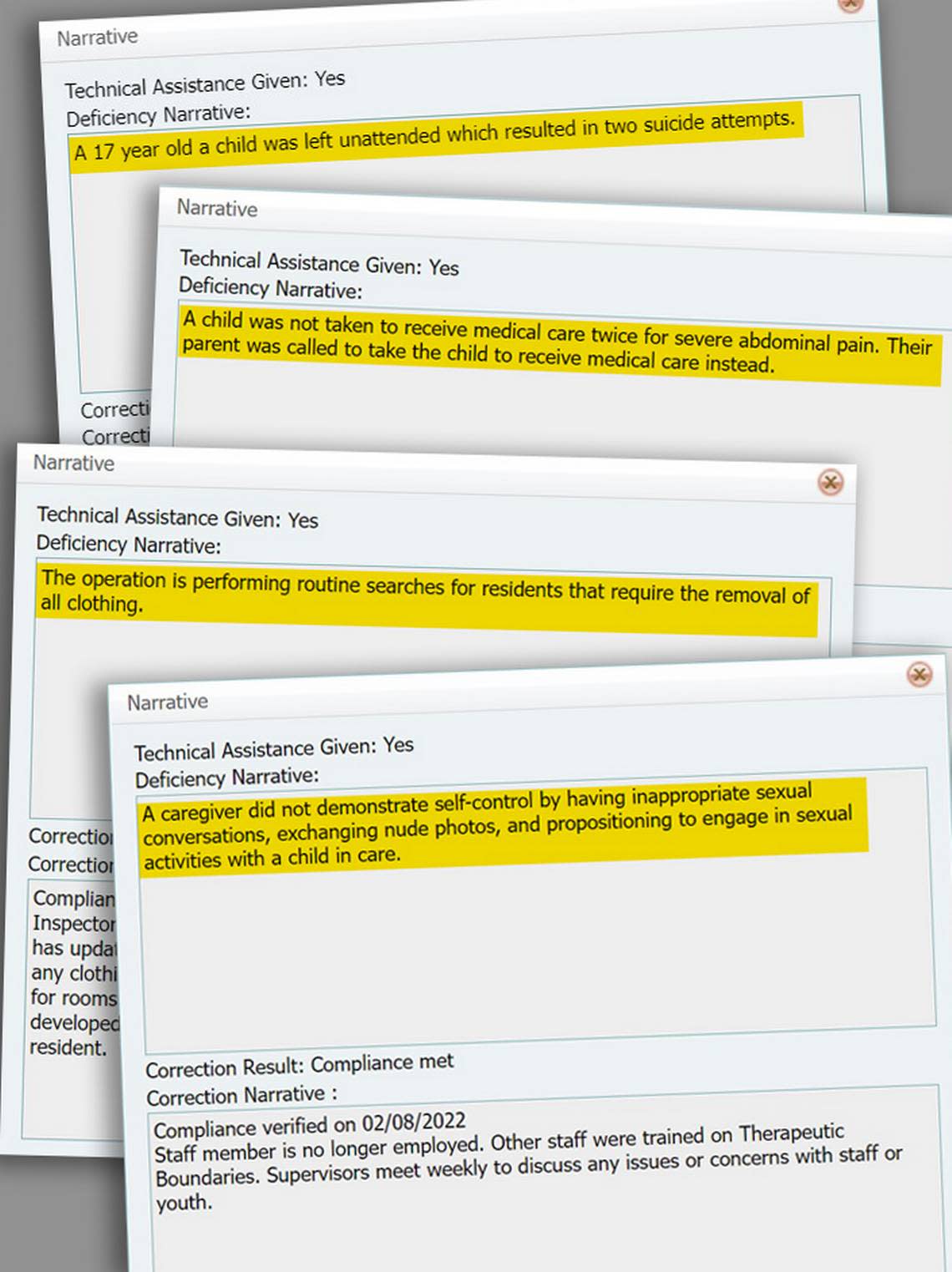

But a Star-Telegram investigation has revealed that Fort Behavioral was cited for scores of violations of state laws and regulations in the two years before the shutdown. Children harmed themselves, fought each other, had sexual contact, took unauthorized medications and ran away, according to state records. At least one staff member sexually abused a child, documents show. Another staff member physically fought a child, while others used aggressive or inappropriate restraints on children numerous times.

In the two years before Fort Behavioral’s shutdown, the facility had the second-highest number of violations among similar types of centers in Texas, according to state data analyzed by the Star-Telegram.

And since Fort Behavioral Health was allowed to reopen under state-ordered probation, regulators have cited the facility at least 30 more times, including instances where staff did not properly supervise children, which in one case resulted in an unsupervised teenager attempting suicide twice.

Parents who entrusted their high-needs children to Fort Behavioral’s care say they were unaware of the extent of the problems. The facility, which employees and families refer to as “Fort,” offers round-the-clock programs for autistic adolescents, as well as those with mental health and substance abuse diagnoses.

For some families, Fort Behavioral represented a rare opportunity for intensive and specialized care, which few facilities in Texas provide. The reality of mistreatment, or an absence of treatment, has felt to some of those families like a betrayal.

Elvia Espino placed her son, Alex, into Fort Behavioral’s Camp Worth program twice in 2022. (That program is separate from the Camp Worth facility on East Seminary Drive that closed in mid-June under state scrutiny and is owned by a different entity.) Espino pulled her son out of Fort Behavioral after 21 days, more than a week early.

Alex, now 13, said he felt unsafe while he was at Fort Behavioral’s Camp Worth, especially because other children would sometimes be violent and start fights.

“The camp was just very scary for me,” Alex told the Star-Telegram in an interview conducted with his mother. “Nobody deserves to go to the camp.”

Espino said she believes her son left the program more traumatized than before. That process of searching for help, and instead finding more harm, has been exhausting, she said.

“It’s like calling 911 and being hung up on,” she said. “Imagine that.”

The Star-Telegram’s investigation included scouring thousands of pages of state documents, police records and wrongful termination lawsuits, as well as interviews with five former patients or their families and 12 people who have worked at Fort Behavioral. In addition, the Star-Telegram shared its findings and the violation records with child care advocates or experts, as well as representatives of the state agencies involved. Those documents and interviews together showed a facility rife with problems, including chronic understaffing, a culture of underreporting problems and an environment that allegedly prioritized profit over care.

Fort Behavioral executives declined numerous requests for interviews. CEO Stephen Mallick, in an email response to the Star-Telegram’s questions, said allegations must be reported to the state “regardless of whether there are concerns as to the truth of the allegations.”

“Investigations and allegations are a part of the daily lives of residential treatment centers,” he wrote. He did not respond to questions about wrongdoing cited and upheld by state regulators, or about the management and workplace problems described by former employees.

Two years of citations

Fort Behavioral Health opened in 2019 in a medical complex in southwest Fort Worth, off Oakmont Boulevard and Chisholm Trail Parkway. The facility also has an adult program operated and licensed separately from the adolescent unit. Fort Behavioral is owned by Bobby Patton, a Fort Worth investor and co-owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team.

Several former employees said Patton isn’t involved in Fort Behavioral’s daily operations. (When the Star-Telegram reached out to Patton over email, he directed questions to Mallick and added, “I don’t know much except that it doesn’t seem very profitable.”)

As early as August 2021, Fort Behavioral began accepting foster children through Our Community Our Kids, the organization that heads up privatized foster care in the Fort Worth area.

Some former employees said that’s when Fort Behavioral’s problems seemed to become worse. All of the employees interviewed by the Star-Telegram agreed to speak on the condition they would not be identified, saying they feared retaliation. The Star-Telegram verified their identities and employment.

From January 2021 to January 2023, state regulators cited at least 75 violations at Fort Behavioral. That’s the second-highest number in Texas among 31 facilities that provide residential treatment to similar populations, according to a Star-Telegram analysis.

About one-third of Fort Behavioral’s violations were considered high risk, with an additional 20 considered “medium high” risk.

The state’s publicly available data isn’t a complete record of offenses and doesn’t include context or explanations. However, the citations listed have already gone through a review process and are no longer subject to appeals. Among Fort Behavioral’s violations:

Three times in 2021, children had sexual or inappropriate contact with each other, including one instance where a group of children also “used unauthorized medication.”

In June 2021, at least two children took “non-prescribed over the counter medications,” and staff then did not provide them with proper medical attention.

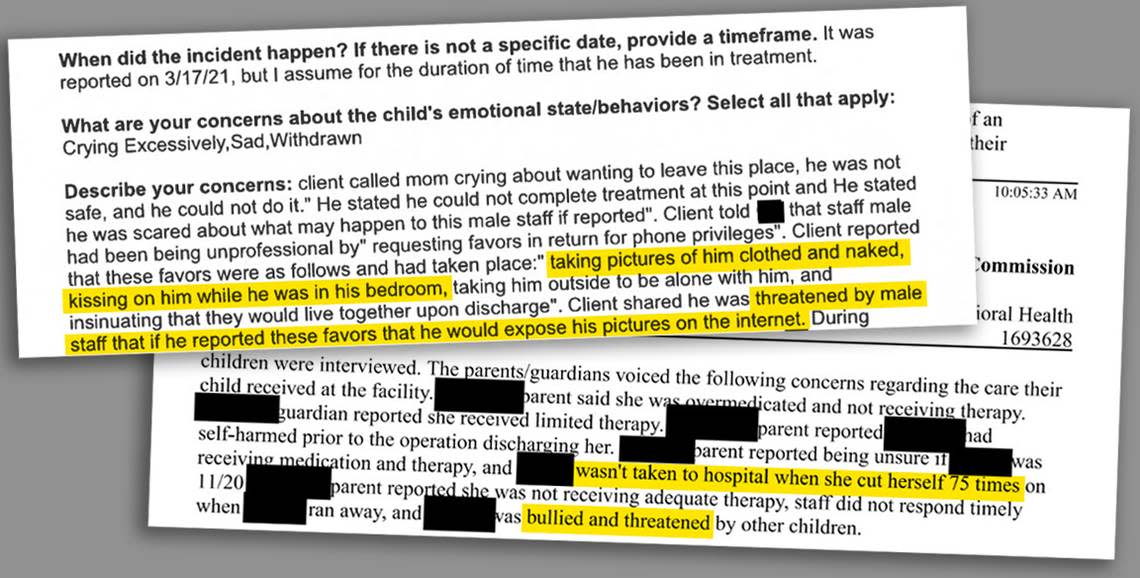

State regulators issued several citations in August 2021 for sexual abuse and exploitation of a child in care. According to the state database, a caregiver was coercing a child “to engage in inappropriate relations” and was “exchanging nude photos” with the child. While it’s not clear if it’s the same situation, state intake documents record a March 2021 report with similar details, where a child at Fort Behavioral called his mother crying, saying that he wasn’t safe. The child said a Fort Behavioral caregiver had been “taking pictures of him clothed and naked, kissing on him while he was in his bedroom, taking him outside to be alone with him, and insinuating that they would live together upon discharge.” The caregiver said he would put the child’s photos online if the child told anyone. Records show the abuse was suspected to have been going on since the child began treatment. The database notes that the staff member involved in the August 2021 citations was no longer employed at the facility.

In May 2021, Fort Behavioral allowed a doctor to examine children without another staff member present.

Also in May 2021, a 14-year-old with a history of self-harm used keys to gain access to a razor, which the child used to self-harm.

By November 2021, the state offered to place Fort Behavioral on a voluntary improvement plan, according to documents obtained by the Star-Telegram. The facility declined, and the citations continued:

Twice in May and June 2022, the facility was cited for improper restraints, including for a staff member pushing a child against a wall and for a staff member restraining a child for longer than a minute.

In June 2022, staff confiscated a hearing-impaired child’s communication devices “as a form of discipline.” No one on staff could use sign language.

In June and December 2022, staff did not intervene when children fought or prepared to fight.

In two citations on the same day in December 2022, a staff member yelled at a child, and a staff member physically fought a child and “had to be held back by another staff to stop the conflict.”

Additionally, Fort Behavioral received citations for administrative problems throughout the two-year period, including failing to properly conduct background checks and staff training.

When asked about the violations, Mallick — the Fort Behavioral CEO — referred to three sexual abuse allegations that the state investigated in 2023 and closed without action. Records of those unsubstantiated allegations are not publicly available and were not included in the Star-Telegram’s analysis.

“There was no sexual abuse of a child at Fort Behavioral Health,” Mallick wrote in an email to the Star-Telegram. “This allegation was independently investigated by the appropriate authorities within the State of Texas.”

When pressed about the sexual abuse citations that the state issued in August 2021, involving photographs of a child, Mallick responded that he stood by his statement that there was no sexual abuse at Fort Behavioral. He pointed to a January 2022 letter in which the state said the facility was in compliance with child protection rules.

‘Extremely, extremely vulnerable’

The scope of violations at Fort Behavioral doesn’t mean that every child in treatment has an entirely negative experience.

One former patient, now an adult, said she was traumatized by the fights and violence she saw at the facility. But her stay at Fort Behavioral “did help me get my life back on track.”

“In a way, I’m grateful, but I also did have some trauma for a while — a lot — from that place,” said the woman, who requested anonymity due to mental health stigma.

Raymond Vail and Charity Harkey-Vail, of Oklahoma City, whose daughter was discharged from Fort Behavioral during the temporary shutdown in January, said the teenager seemed to have a good experience. Aside from some mild bullying, she was doing well during her two weeks there, Vail said.

Some of Fort Behavioral’s violations are fairly common in residential facilities, according to Kate Murphy, the director of child protection policy at Texans Care for Children, a nonprofit advocacy organization. Many facilities lack adequate supervision, for example, due to understaffing. Allegations such as sexual abuse are less common, she said.

But the consequences of even minor infractions can be exacerbated by the vulnerabilities of high-needs children, such as those housed at Fort Behavioral.

“It is an extremely, extremely vulnerable population that we’re talking about,” Murphy said. “These are kids who are the most in need of extra help and support to make sure that they’re OK.”

Alicia Glass Pulley said she would have never placed her daughter at Fort Behavioral if she had known the extent of problems described by the Star-Telegram’s reporting.

“I love her, and I need somewhere that’s going to actually take care of her and watch her, and not do any harm to her,” Pulley said. “People not following rules on doing some little things here and there or whatever, I probably would’ve overlooked that. But these big things? No.”

Pulley said she doesn’t understand why Texas regulators hadn’t taken more drastic measures before the temporary shutdown in January, which happened 24 hours after her daughter’s arrival.

“For it to take this long, or somebody to not question it before that, just is kind of crazy to me,” Pulley said. “To me, they shouldn’t even be allowed to be open. I don’t even (know) how they reopened back up. I’m shocked.”

In an emailed response to questions, a spokesperson with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission said the agency works with facilities to reduce risks and imposes enforcement actions when a facility can’t reduce risks on its own.

The Star-Telegram asked HHSC specifically about the August 2021 sexual abuse citations, which were more than 16 months before the shutdown.

“In the situation identified, HHSC identified a pattern of non-compliances, completed expedited monitoring and follow-up inspections until an enforcement action was imposed,” an agency spokesperson replied in an emailed statement.

‘I don’t trust these people, OK?’

But several former Fort Behavioral workers say problems were more extensive than HHSC records show.

At least six former employees described systemic problems with internal documentation and state-mandated reporting.

Regulators noticed, too. They cited Fort Behavioral for failing to document care plans and not keeping records on physical restraints. Twice, the state found facility logs that said staff checked on children when they had not, including one case where the state determined a staff member was falsifying the logs.

At least twice before the shutdown, Fort Behavioral staff were found to have improperly interfered with child complaints or investigations. The first time, in 2020, staff conducted their own investigation of an incident before state regulators could interview children. Then in late 2022, staff “interfered with a child’s attempt to make a complaint over the phone” by not giving the child privacy, and by “regularly” listening to or monitoring children’s calls. (The facility received another interference charge in the days before the shutdown in January.)

One father, Matthew Maxwell, told the Star-Telegram that when he picked up his son from Fort Behavioral Health in 2022, he had to immediately take the boy to an emergency room for a swollen finger, which proved to be fractured. Fort Behavioral had not taken the 12-year-old for treatment after a staff member accidentally shut the boy’s hand in a door earlier that day, Maxwell said. When he filed a complaint with the state, he wrote that he “cannot help but to feel that FBH has gone out of their way to evade their responsibility for having injured my son.”

The state’s citations don’t provide explanations for staff’s actions.

But an internal Fort Behavioral webinar obtained by the Star-Telegram suggests the facility encouraged staff to distrust state regulators.

The 2021 staff training, led by outside attorney Norman Ladd, was an overview of how to respond to state investigators who might come to the facility in response to abuse or neglect allegations. Ladd placed the training in the context of increased investigative scrutiny, due to ongoing federal oversight of the Texas foster care system.

Outside child care experts say it’s true that the state has stepped up surveillance in recent years. But the webinar took it a step further.

“The next thing that you need to remember is (state investigators) are not on your side,” Ladd said in the video. “And I hate kinda saying that — well, maybe not so much anymore — but we have really ventured into some very antagonistic waters with the state of Texas.”

Ladd — who initially agreed to an interview but then stopped responding to the Star-Telegram’s messages — said in the webinar that he didn’t mean every investigator was a bad actor. He likened the situation to defensive driving.

“We need to be guarded, OK? We need to be defensive,” he told Fort Behavioral staff.

Ladd also emphasized that the state’s abuse and neglect investigations, if substantiated, could have long-lasting implications for child care workers, such as preventing them from getting jobs in the field or coaching their children’s sports teams.

“I know I sound a little bit like the crazy tin foil hat guy, but I don’t trust these people, OK? And I don’t trust them because I have a long track record of showing over and over and over and over again, situations they cannot be trusted in,” Ladd said.

Multiple former employees told the Star-Telegram that in their experience, Fort Behavioral’s culture discouraged transparency.

A former director at Fort Behavioral said complaints made to higher-ups “never went anywhere.” Another said staff was told directly to not call police if foster children ran away. One former employee with administrative responsibilities said he believed there was “a vast difference” between what’s happened at Fort Behavioral and what the state knows about.

Managers of residential treatment centers — and the tone they set — are key in keeping children safe from abuse and neglect, according to Christie Carrington, who retired from Texas Child Protective Services and now works for the Texas State Employees Union.

“The management has to take a very strong position, so that the culture amongst that staff, they know that this is not something somebody is going to look away from,” she said. For these children, “their safety has to be given a top priority, even more so than the average person, because people take advantage of vulnerable people.”

‘The bottom dollar’

Five former employees who worked at Fort Behavioral before the 30-day shutdown in January said the facility seemed to be focused on money.

While some offer the caveat that they understood a medical facility must balance patient care with revenue, they said they felt Fort’s scales were tipped toward dollar signs.

Mallick, Fort Behavioral’s CEO, would say things like, “‘Either y’all start filling up these beds to bring more money, or I’m going to fire people in this room,’” one former director told the Star-Telegram. “And that’s when I realized it’s not about the care, it’s about the money.”

Another former employee, a nurse, said she heard Mallick explicitly state his financial focus in a meeting.

“He did say, ‘I don’t care about recovery,’” the former employee said. “He’s there for the bottom dollar.”

That impression is reflected in court documents for wrongful termination lawsuits against Fort Behavioral. In a deposition, a former employee said that Mallick “said we should not be leaving days on the table,” suggesting keeping children in treatment as long as possible.

Some former staff also told the Star-Telegram that they worried that the facility began accepting foster children through Our Community Our Kids primarily because of the revenue those placements would bring.

Under the current payment system, with rates updated in September, the state pays $50 to $480 per day for every foster child, depending on the level of care needed. Residential treatment centers are typically at the higher end of the care spectrum.

Mallick said in a court record that housing foster children requires less work than housing those with behavioral needs. In a signed affidavit responding to a wrongful termination lawsuit again the facility, Mallick said that Fort Behavioral’s “programming for (Our Community Our Kids) patients is less stringent than the programming that is required for private pay patients.”

A former Fort Behavioral employee, who had administrative responsibilities, called the system “absolutely broken.”

Fort Behavioral “saw an easy way to make money with low clinical demands. But you’re going to work for it, and I don’t think they had the culture or the staff to make it.”

A ‘fear-based’ workplace

Several former employees interviewed by the Star-Telegram described an environment where workers lived in fear of being yelled at or unceremoniously fired.

Some of them said Mallick or other executives asked them to do things that were illegal or against generally accepted rules.

Two former nurses told the Star-Telegram that Mallick asked them to provide medical care to the foster children without orders from an appropriate doctor. The nurses said they feared that if they did as Mallick said, they would lose their licenses; if they refused, they’d be fired. Instead, they both said, they quit.

“You can’t manipulate the law,” one of the nurses said. “And they have.”

One former employee, in a 2021 wrongful termination lawsuit, said Mallick demanded she admit children whose needs outstripped the facility’s resources. When she declined, she was fired, according to the lawsuit. (That employee declined to be interviewed by the Star-Telegram. Her case was ultimately resolved through a settlement.)

Another former employee alleged in a 2022 wrongful termination lawsuit that she lost her job after pointing out that the facility “was not complying with multiple state regulations,” including employee-child ratios and background checks. She was demoted under a “restructuring” that took place nine days after she started, then fired. That lawsuit was settled and closed in August.

A lawyer for Fort Behavioral was known to send cease and desist letters to employees upon their firings, according to several people. A copy of a letter obtained by the Star-Telegram includes a threat of a lawsuit if the former employee said anything derogatory about Fort Behavioral.

“If you said anything, if you challenged him, if you made him mad, you were getting a cease and desist, and you were getting walked out of the building and losing your job,” one former employee with HR-related responsibilities said.

At least four former workers said Mallick would scream over the phone and in meetings, and make threats about firing people or not paying them.

“It was fear-based. A lot of it was fear-based,” one former director said.

Former employees said they believe such an environment — which one described as “the worst culture in the world” — contributed to high turnover.

Espino, whose son Alex was at Fort Behavioral twice in 2022, said she was shuffled through at least four lead staff members over each of her son’s stays.

Separately, a former worker with supervisory responsibilities described how direct care workers without licenses to provide therapy would lead group sessions “all the time.” The workers would show movies about addiction or recovery. Sessions that should have been conducted by trained therapists were instead led by Sandra Bullock in “28 Days” or Denzel Washington in “Flight.”

“I think (Mallick) creates an environment where everyone is in this survival mode, and then that brings out the worst in people,” the former employee with HR-related responsibilities said. “I think that (if) you take all of those same people and you give them a different boss, and it would have turned out completely different.”

The 30-day shutdown

By the time the state called families in January to tell them to pick up their children immediately, the foster children at Fort Behavioral were already on their way out.

The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services officially pulled its foster placements on Jan. 17 due to “concerns about appropriate care,” according to spokesperson Marissa Gonzales. All 23 of those kids were out by the end of the month.

Facility shutdowns are fraught. Allowing unsafe facilities to operate puts children at risk. But sudden closures mean high-needs children might go without treatment, since so few specialized clinics exist. During Fort Behavioral’s shutdown, several families reported “catastrophic” impacts on their kids’.

A total of 40 children were discharged from the facility, an HHSC spokesperson told the Star-Telegram at the time.

It’s still not clear what specifically triggered the shutdown, but documents obtained by the Star-Telegram suggest it was connected to staff’s physical violence against children.

On Jan. 26, the Health and Human Services Commission issued its 30-day shutdown order. In emails to parents, Fort Behavioral executives denied that the facility was unsafe and blamed the allegations on vindictive former employees.

Among 1,500 pages of state intake reports that the Star-Telegram obtained, a Feb. 5 report says a staff member at Fort Behavioral had been putting children “in unnecessary physical restraints,” including choking a child, and that the facility was closed “pending investigations relating to (that) behavior.”

The state also investigated three allegations of sexual abuse, which were closed without action on Feb. 16 because of “insufficient evidence,” according to a letter from the state that Mallick provided the Star-Telegram.

During the shutdown, Fort Behavioral sued the state, saying the closure was without due process or sufficient evidence. That suit was resolved with an out-of-court agreement that allowed Fort Behavioral to reopen under one year of probation.

In an emailed statement, the HHSC spokesperson said the agency determined Fort Behavioral “could reduce risks by complying with the conditions identified in the probation.”

Fort Behavioral under probation

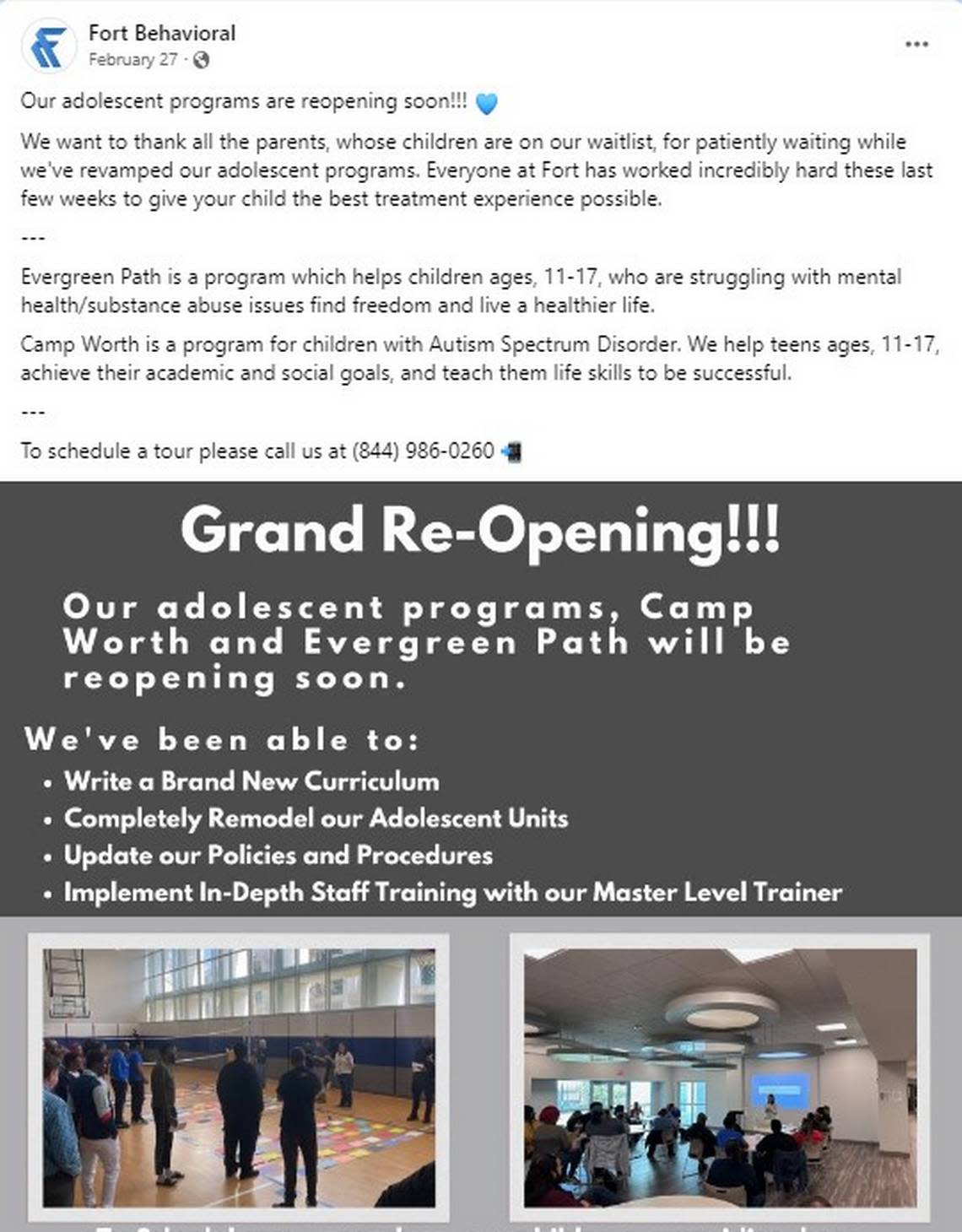

On social media, Fort Behavioral framed the lifting of the closure order as a “Grand Re-Opening” with “revamped” adolescent programs. There was no mention that the 30-day closure had been mandated by the state.

Fort Behavioral’s reopening, in February, came with 15 probation conditions, including additional staff training and monthly meetings with each child. HHSC will also “conduct unannounced inspections monthly” to make sure Fort Behavioral is meeting the requirements.

However, the foster children have never returned.

The state Department of Family and Protective Services no longer places foster children at Fort Behavioral. Our Community Our Kids, the organization that oversees foster care in the Fort Worth area, said in an emailed statement that it “does not have plans to reestablish a relationship.”

The state Health and Human Services Commission, which regulates facilities such as Fort Behavioral, is separate from the Department of Family and Protective Services. HHSC said it “did not consider the DFPS (foster) placement decision” when deciding how to handle Fort Behavioral’s closure or reopening.

Murphy, the advocate at Texans Care for Children, said pulling foster kids from a facility that’s still permitted to house and treat other kids creates a “two-tiered system.” All highly vulnerable children should be well-protected, she said.

“We really need to, as a state, think about how we can make sure that all kids who are in a treatment facility are receiving high levels of care in a safe environment because that’s what they need, and that’s what they deserve,” she said.

‘Somebody’s going to lose their child’

Since Fort Behavioral reopened in February, the state has cited the facility at least 30 times, for both minor and serious violations.

In late February, the facility was cited after an unsupervised 17-year-old attempted suicide twice. That incident also was not initially reported, as required by law, according to the state database.

In May, Fort Behavioral received a citation after a child entered several other children’s rooms during the night without staff knowing about it. On the same day, the facility was cited for failing to supervise the children, which allowed teenagers to “engage in sexual activity.”

When one worker started at Fort Behavioral after it reopened, she noticed red flags almost immediately. There was no programming, she told the Star-Telegram, which made it feel like staff were “literally just babysitting.”

It was the same concern raised by employees who worked there before the shutdown: Fort Behavioral was taking high-needs kids with complex traumas and diagnoses, and putting them into a facility with nothing to do.

The post-reopening employee also said she felt the facility kept children who belonged elsewhere. The employee described rampant understaffing, which left her or others to care for a dozen or more children with little help. On one understaffed shift, the former employee said a child attempted suicide. And, while caring for that child, the other children were left essentially unsupervised.

“They kept certain kiddos that they couldn’t provide the appropriate care for, because of the dollar sign that came with them,” she said. “By keeping them, you’re putting these children’s lives at stake.”

The child who had attempted suicide survived, the employee said. But the danger of the staffing levels — for both the workers and the children — felt undeniable.

“It was extremely unsafe,” she said. “Somebody’s going to lose their child, under the care of Fort.”

A couple of families told the Star-Telegram they’d like to see Fort Behavioral rehabilitated, so it can be a resource to the community.

But nearly all of the former employees interviewed said they didn’t see how Fort Behavioral could become a safe place for children, at least not without overhauls that far outstrip the state’s probation conditions.

“Every bone in my body per my experience says it needs to be shut down,” one former director said.

Another former employee had a specific plea. If the state won’t shut down the facility permanently, maybe the facility’s owner will.

“My hope here is that Mr. Patton will see this and say, ‘Yeah, this was a bad idea, let’s just call it quits.’”