Kathleen Hanna is a troubadour unafraid to speak out

It was never about fame. While artist and activist Kathleen Hanna stood out as a leading figure in the 1990s Riot Grrrl movement, she actively worked against the role. Rather, Hanna’s focus was on community, forged through collective effort. What catapulted her to this position and fixed her in the spotlight was the visibility of her band Bikini Kill. With mainstream media coverage came a distortion of the movement’s mission. Quickly the movement became co-opted by an anodyne rallying cry for “girl power.”

Yet in the decades that have passed, what’s endured is a genuine punk spirit, fed by Hanna’s ongoing force as a gutsy, proud feminist who helped other artists and fans fight back against abuse and discrimination. She never gave up on being determined, yet playful and brash at the same time. Now is the time to set the record straight.

Hanna’s first book will be released May 14. “Rebel Girl,” a memoir subtitled “My Life as a Feminist Punk,” is a far cry from the handcrafted zines that Hanna archived at New York University in 2010. Yet it possesses the same vibrancy as those fliers, notebooks and ephemera. The book opens with her childhood and coming of age as an art student at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Wash., then moves on and off the road as a musician and lead singer in the bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre, among others. With this book, she creates space for her own story as well as the larger context of her time and the need for art as a creative agent of empathy and change. Hanna is a troubadour unafraid to speak out.

Talking over the phone in February before a tour with Bikini Kill, Hanna mused, “I just always thought I had a pretty uneventful life.” But the more Hanna sifted through her memories while writing her exuberant memoir, the more she gained the perspective that hadn’t been clear to her before now. “Wait,” she said, “this is actually really eventful.”

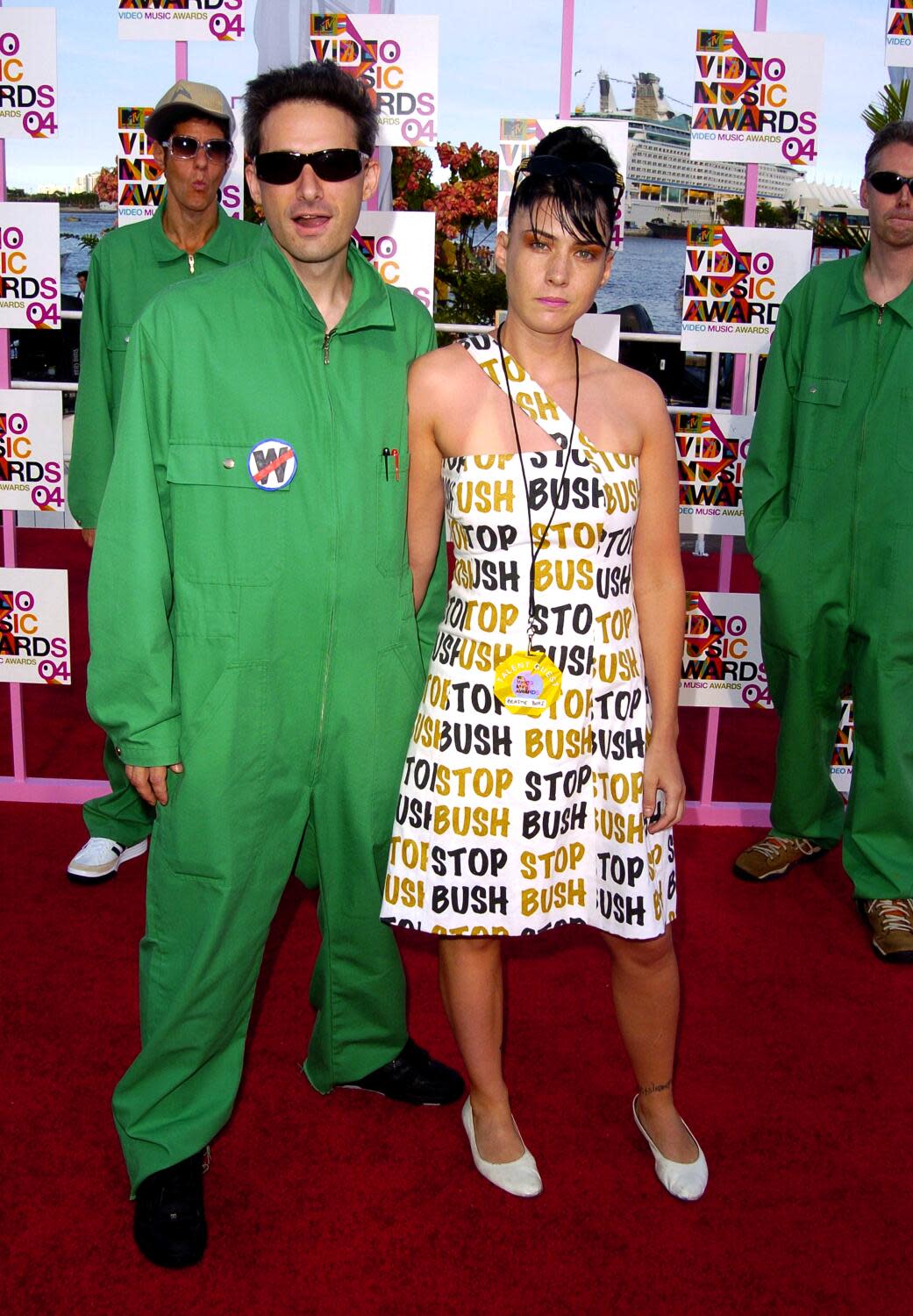

With its episodic style of vivid, swift chapters and Hanna's kinetic voice, “Rebel Girl” is a bold portrait. For the sake of late 20th century history alone, it’s a crucial book about feminist politics and art. But it’s also a tender examination of a woman who survived abuse and sexual assault. You’ll find the origin stories of her bands; chronicles of her friendship with the late Kurt Cobain; the tour where she fell in love with her husband, Adam Horowitz, better known as Ad-Rock of the Beastie Boys; recording with Joan Jett; and getting punched by Courtney Love at Lollapalooza — just the boldface highlights.

Read more:Kathleen Hanna on the return of Le Tigre, 'gross' fans who won't mask up and the summer of Beyoncé

But more important, Hanna talks about her complicated family history, the art gallery she began with friends during college, the challenges of a rapidly growing social movement, the gritty truth about life on the road as a musician and the enduring friendships that saw her through the challenges she faced as a woman in punk.

Scenes among friends, including Bikini Kill bandmate Tobi Vail, Le Tigre’s Johanna Fateman and musician, artist and the founder of Mr. Lady Records, Tammy Rae Carland, highlight the power of friendship in an industry that thrives on competition.

Faced with the solitary nature of writing, Hanna drew from her experience as a musician, recognizing that she does better “in collaborative situations.” She quickly recognized that the “aloneness” of writing meant “you don't have anybody to decompress with” as you would “after a crappy show.” Yet she carried on, and after her years of writing, Hanna found herself flush with material. The book was originally more than 600 pages long. A friend of Hanna’s , writer Ada Calhoun, flew to California from New York to help her pare the book down by 300 pages.

In the end, Hanna felt that the memoir “was really a way for me to make a narrative out of my life to get distance from some of the harder things” so she could say to herself, “‘OK, that was really painful at the time, but now it's a funny story.’ And maybe that's not the healthiest thing but it really works for me to turn something into a funny story or even just a story with a beginning, a middle and an end.”

While this may sound simple, Hanna sees it as a blessing that isn’t granted to everyone. “I felt kind of lucky. I had a lot of stories that came full circle, and I wanted to write them all down.”

Read more:Punk icon Kathleen Hanna takes her ‘girls to the front’ mantra to T-shirt line for Togo schoolgirls

While a memoir seems a natural next accomplishment for someone with a nearly 35-year career in arts and activism, it wasn’t necessarily fated that she would write a book.

More than a decade ago, the documentary “The Punk Singer” chronicled her life and work. This book takes a deeper, longer look from Hanna’s singular perspective. It’s a gift to readers that Hanna bided her time before speaking for herself. Interestingly, one can look at one episode in her life as a reason to consider the medium as much as the message.

Now 55, living in Pasadena with Horowitz and their 10-year-old son, Julius, with her mother nearby, along with three decades of art and music under her belt, Hanna can say that she is solidly a writer. Her memoir marks a new chapter in her life. She reflects, “I really wanted to write a book because I'm in this transitional period in my life.”

While she has no desire to quit music, by capturing her history in a memoir, she puts to rest an enormous period of her life in order to make space for something new.

Asked what she wants to do next, Hanna says, “Honestly, I would really like to be a comedy writer.” While this initially sounds like a pivot, it makes complete sense. Hanna is a tremendously warm and funny person. Both in conversation and in her music and writing. Not only is she deeply aware of the ways that others engage with her work but she also notes that “one of the things that is really different about writing a book than being in a band is the lack of collaboration.” Hanna said she “would like to write comedy for other people, for TV, theater or film. I'd love to be in a writers room.”

Comedy is another reason Hanna has taken to life in California after more than 20 years living in New York. She and her family relocated shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Actually, when I moved to New York originally” — in the early aughts — Hanna thought to herself, “‘I'm leaving punk. And I'm going into the comedy scene.’ And it didn't quite work out.”

The scene is different and more accessible in Los Angeles.

“The shows are really small. You can just go right up and talk to people. There's a lot more people here whom I knew from San Francisco and from past experiences in the punk scene, who are now into comedy.” Hanna even hosted a comedy show with comedian Kate Berlant at her home.

Her life seems no less busy than it was 30 years ago, but Hanna’s confidence gives her the ability to transition from concert tours to book events without any challenge to her identity. With age comes perspective and wisdom. She sees her work as part of a larger project. This applies to the material she cut from the book. Hanna is sanguine and remarked, “I'm lucky because I'm older. And so I know that if I don't use this material for this, I can use it for something else.” She can see herself weaving material into a short story, an essay or article, or even an Instagram or TikTok post. “It's not like the material’s lost.”

LeBlanc is a writer whose work has been published in Vanity Fair, the Believer and the New York Times Book Review, among others.

Get the latest book news, events and more in your inbox every Saturday.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.