How the House GOP fell to pieces

Republicans in the House of Representatives have now stumbled through a second fruitless day of gridlock, with GOP leader Kevin McCarthy still unable to win over the hard right of his caucus in his quest to become speaker.

And because the House cannot function until a speaker has been chosen, the GOP’s paralysis could have wide-ranging impacts on everyday Americans. The impasse could even hamper the ability of Congress to appropriate money if there is a natural disaster, an economic crisis or a military conflict.

The U.S. government will begin defaulting on its debt payments by this summer if Congress does not raise the debt ceiling, a failure that would risk sending the economy into a tailspin.

Analysts warn that a weak Republican speaker makes that outcome more likely, as whoever is chosen will not have the influence necessary to force the fractious GOP caucus into a necessary compromise with Democrats.

Congress is also slated to pass another farm bill this year, a five-year plan with massive implications for food policy, agriculture, the environment and other matters.

Until the House chooses a speaker, lawmakers cannot help their constituents with vital services such as applying for Social Security and other benefits.

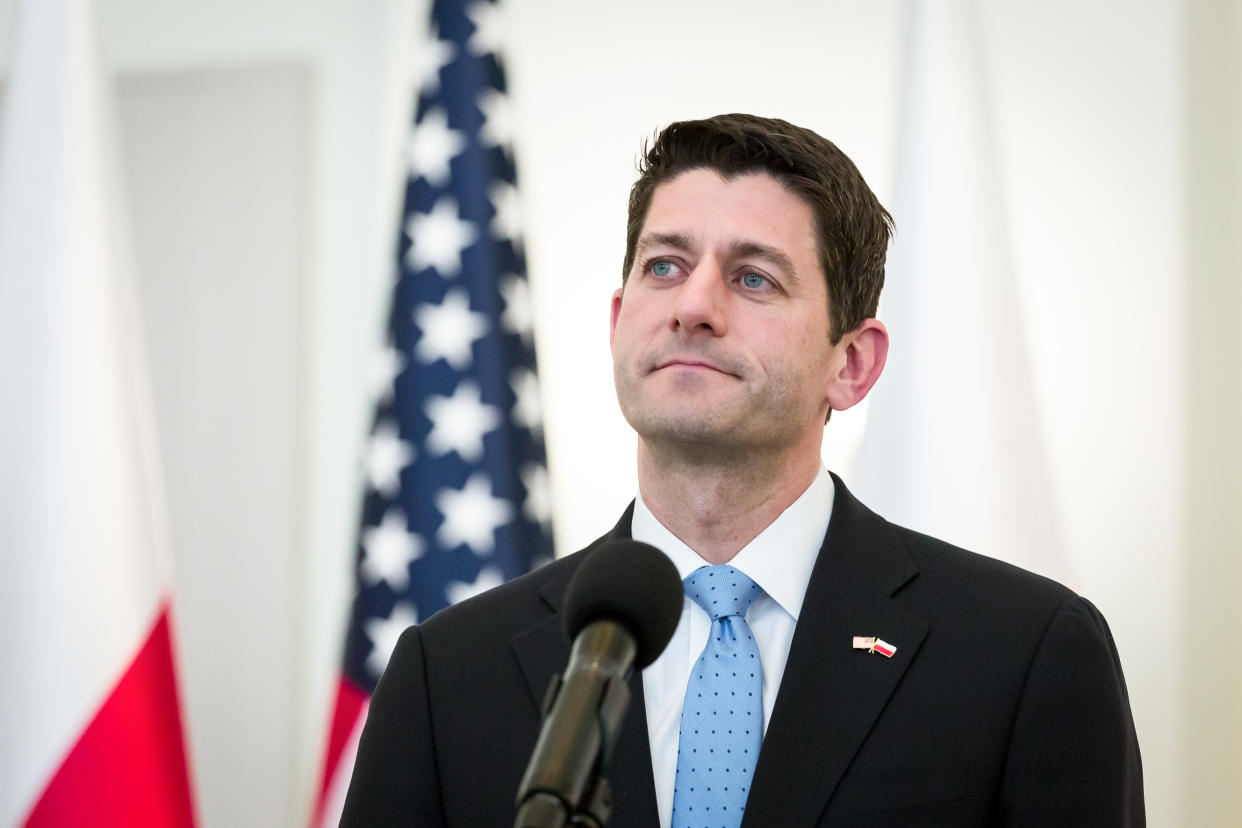

The House of Representatives, with members elected every two years, instead of every six as in the Senate, “is supposed to be the body closest to the people,” Brendan Buck, a past adviser to former Republican Speaker Paul Ryan, told Yahoo News.

“And when [the House] can’t operate at all, it can’t be expected to be responsive to their needs. There are basic responsibilities of the House, but we also need Congress to act when things are urgent,” Buck said. “A complete breakdown in our legislature tells people and the world that we can’t be counted on to solve problems and provide stability.”

The House GOP’s current troubles stem from years of discord within its ranks.

For over a decade, the GOP has been hobbled by a faction that sees getting nothing as better than something, if it cannot get everything it wants. Sometimes this faction has actually wanted nothing.

While uniquely embarrassing, the stalemate over the speakership is just the latest in a series of moments of gridlock caused by the party’s right wing.

In the debt ceiling crises of 2011 and 2013, House Republicans refused to raise the limit for borrowing without concessions and triggered stock sell-offs and economic tremors.

In the fall of 2013, vowing to “defund Obamacare,” Republicans in the House and Senate led a campaign that never stood a chance of succeeding but led to a 16-day government shutdown.

In 2015, Republican Speaker John Boehner decided he’d had enough of trying to lead the increasingly chaotic House GOP and abruptly quit his post. McCarthy, R-Calif., made a bid to replace him but withdrew his name after it became clear he did not have the votes. Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., was then chosen as a compromise candidate.

Ryan, long seen as one of the party’s brightest rising stars, struggled with the demands of the position. In 2018, even though the GOP controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House, another three-day government shutdown occurred as Democrats engaged in hardball politics comparable to what Republicans had done in the past.

Later that year, Republicans lost control of the House. Ryan, bruised and battered from trying to lead the House GOP, declined to run for reelection and, like Boehner before him, left politics altogether.

Then it was finally McCarthy’s turn. McCarthy, long seen by his Republican colleagues as an affable if limited figure, became GOP leader in a House run once again by Democrats. He spoke bullishly of winning back the House by a comfortable margin in the 2022 elections, but emerged with a slim majority, only to be bullied by the hard-liners he would have to court to become speaker.

So the party remains on the same fractious trajectory it has been on for the past decade or more. Its robust antigovernment wing, having learned the politics of social media celebrity and TV fame from former President Donald Trump, is if anything more intransigent than ever before, and at times unable to even articulate its demands.

The GOP has long had a libertarian streak. President Ronald Reagan famously said in his 1981 inaugural address that “government is not the solution to our problem.” But Reagan’s Republicans were also interested in governing, and in the necessary compromises with Democrats that that entails.

When Democrats won back the White House under Bill Clinton, however, a new, hard-nosed generation of Republicans took power. Grover Norquist, an anti-tax advocate who gained great influence in Republican politics, famously said he wanted to shrink the government to the point where he could “drown it in the bathtub.”

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, wrote Wednesday that the GOP has been antigovernment so long that it is now “a thoroughly anti-system party. And it is very hard to lead an anti-system party when leadership means being part of the system.”

Some potential solutions to the problem of extremist politics have shown promise. In many races for the House, Senate and statehouses in the 2022 midterm elections, voters roundly rejected right-wing radicalism. If the GOP continues on its current trajectory — and voters continue to punish it for that — it becomes increasingly likely that the party will need to moderate its stance, if only out of necessity.

Certain structural changes could also make representatives more responsive to the will of voters. The state of Alaska, for example, has pioneered one new way of electing members of Congress and its statewide officers: Get rid of party primaries.

Alaska’s system allows anyone to run in one primary, in which the top five vote getters advance to the fall election, and the winner is chosen by instant runoff or ranked-choice voting in which the winner must receive at least 50% of the vote.

Eliminating party primaries takes control of the process out of the hands of a small number of the most hard-line voters on each side. Under the current system, only about 10% of eligible voters cast ballots in party primaries, and only one candidate can emerge from each party’s primary.

So by the time the larger group of voters shows up in the fall election to choose a winner, the choices are limited to two candidates who often have secured their party’s primary by catering to its most extreme members.

An open primary that promotes the top five vote getters to the fall general election allows more moderate, compromise-minded politicians to be competitive. This reform is under consideration in Nevada, and variations of it have been adopted in Maine and in cities in Colorado, Washington state and Utah.