Hospital exams for sexual assault victims are supposed to be free. Many get large bills anyway.

Some victims of sexual assault are paying out of pocket for their emergency room care, even though federal law requires that their forensic exams be free.

In a letter to the editor published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, a group of doctors and researchers calculated the cost of emergency department visits for survivors of sexual violence, using 2019 data from the Department of Health and Human Services.

They found that out of nearly 113,000 emergency visits that year related to sexual violence, 16% resulted in out-of-pocket costs for the survivors.

In those cases, the average cost of care was $3,551 per person. Costs were higher for pregnant people: $4,553 per person, on average.

The Violence Against Women Act, a federal law enacted in 1994, stipulates that people cannot be charged for a forensic exam after a sexual assault. President Joe Biden, then a senator, introduced the act in 1990. In March, he reauthorized the law.

But some medical services — such as emergency contraception or treatment for sexually transmitted infections — are not covered under the act. So in some cases, sexual assault victim are billed for those services; in others, patients are charged for the exam itself, either because of hospital error or because the exam was not conducted by a specially trained clinician, which the law requires for the exam to be free.

The new research did not differentiate between costs that should be covered under federal law and other supplementary medical services. But Samuel Dickman, the lead author of the letter and a doctor at Planned Parenthood of Montana, said that regardless of the source of the fees, "this is a huge, huge problem affecting tens of thousands of Americans each year."

Dickman said he felt compelled to conduct the research after he "took care of patients in Texas and elsewhere who had been assaulted and were facing catastrophically high, impossible-to-pay medical bills."

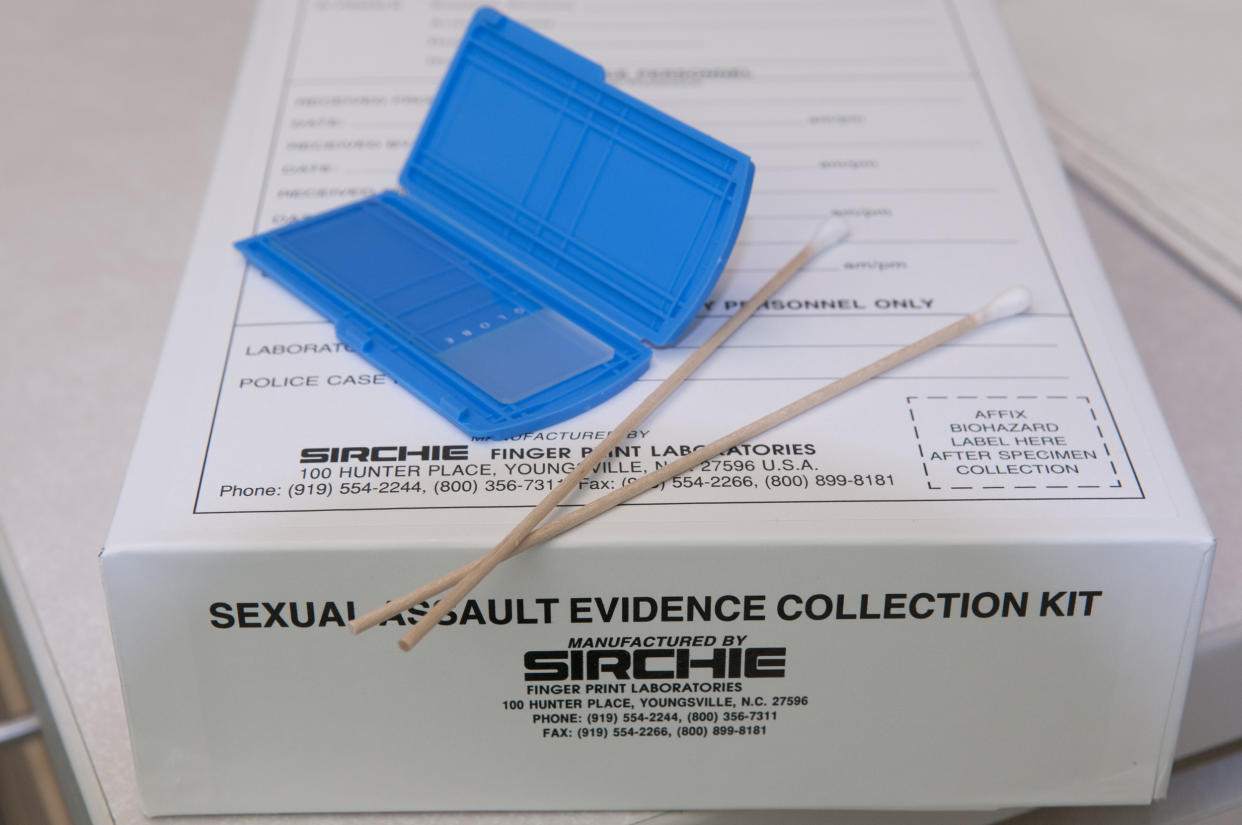

During a forensic exam, a sexual assault victim is treated for immediate injuries, then asked about their medical and sexual history and given a head-to-toe examination that may involve collecting samples of blood, urine, skin or hair. The exam is administered using a "rape kit," which contains materials needed to gather evidence, such as a comb, swabs and envelopes.

But diagnostic testing, counseling, pregnancy tests and the mending of cuts or tears in the skin are all among the services not considered part of that exam.

"It’s difficult enough for victims to find the courage to report and seek help. Charging victims for medical treatment further compounds the offense by committing them to a financial obligation, which in some cases, causes financial hardships. It’s like telling the victim they are responsible for the assault," Traci Sharpe, training director at the anti-sexual violence organization RAINN, said in an email.

The data that Dickman and his team analyzed encompassed all patients who showed up to an emergency room for an issue related to sexual violence, including those who were uninsured. The average cost of care for uninsured patients was $3,673.

Dickman thinks the lion's share of the out-of-pocket charges his study revealed were related to additional services, rather than the exam itself.

But a study published in March by KFF, a nonprofit think tank formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation that focuses on health issues, found that plenty of people are charged for the forensic exam.

That study looked at privately insured women who, based on their medical claims, had likely been treated with a rape kit at an urgent care facility, emergency room or outpatient clinic from 2016 to 2018. The results showed that two-thirds of those women were charged out-of-pocket for at least one standard service involved in a forensic exam. The women spent $347, on average, for these services.

Alina Salganicoff, director of women’s health policy at KFF, said it's possible victims were billed out-of-pocket by mistake because their hospital wrote down the wrong diagnostic code.

But she also pointed to a shortage of accredited nurses known as Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), who must conduct an exam for it to be covered under federal law.

"There’s no obligation for the state to cover the forensic exam that’s conducted by a clinician that’s not a registered SANE," Salganicoff said.

So it's likely that some women sought care from a clinician who didn't qualify. Many hospitals, especially rural ones, don't have a registered SANE on staff. A 2016 report found that some sexual assault survivors in rural areas would have to travel to a metropolitan area two or more hours away to find a SANE.

"I imagine that some patients go to an emergency room that isn’t equipped to offer the forensic exam, and they might be told they need to go somewhere else," Dickman said.

Salganicoff said several organizations that assist victims of sexual assault provide lists of hospitals with forensic exam providers. But many patients don't know to seek them out.

According to the KFF report, some states offer more free medical services associated with the forensic exam than others.

For example, 17 states cover the costs of STI testing, 15 cover preventative HIV treatment, and 11 cover emergency contraception on the same day as the forensic exam. Virginia and Illinois have the broadest coverage; in addition to the services listed above, sexual assault victims there do not have to pay for ambulance fees, drug testing, medications or injections.

But Dickman said more needs to be done on the federal level to help survivors of sexual violence, including expanding the services covered by the Violence Against Women Act. Salganicoff said it's also important to train and register more SANEs and to better educate hospitals and insurers about which services are covered under the law.

"The fact that this study even needs to be done is such a condemnation of our health care system, more broadly than just the failures of the Violence Against Women Act," Dickman said.