Henry Taylor, the democratic king of portraiture, makes his L.A. homecoming at MOCA

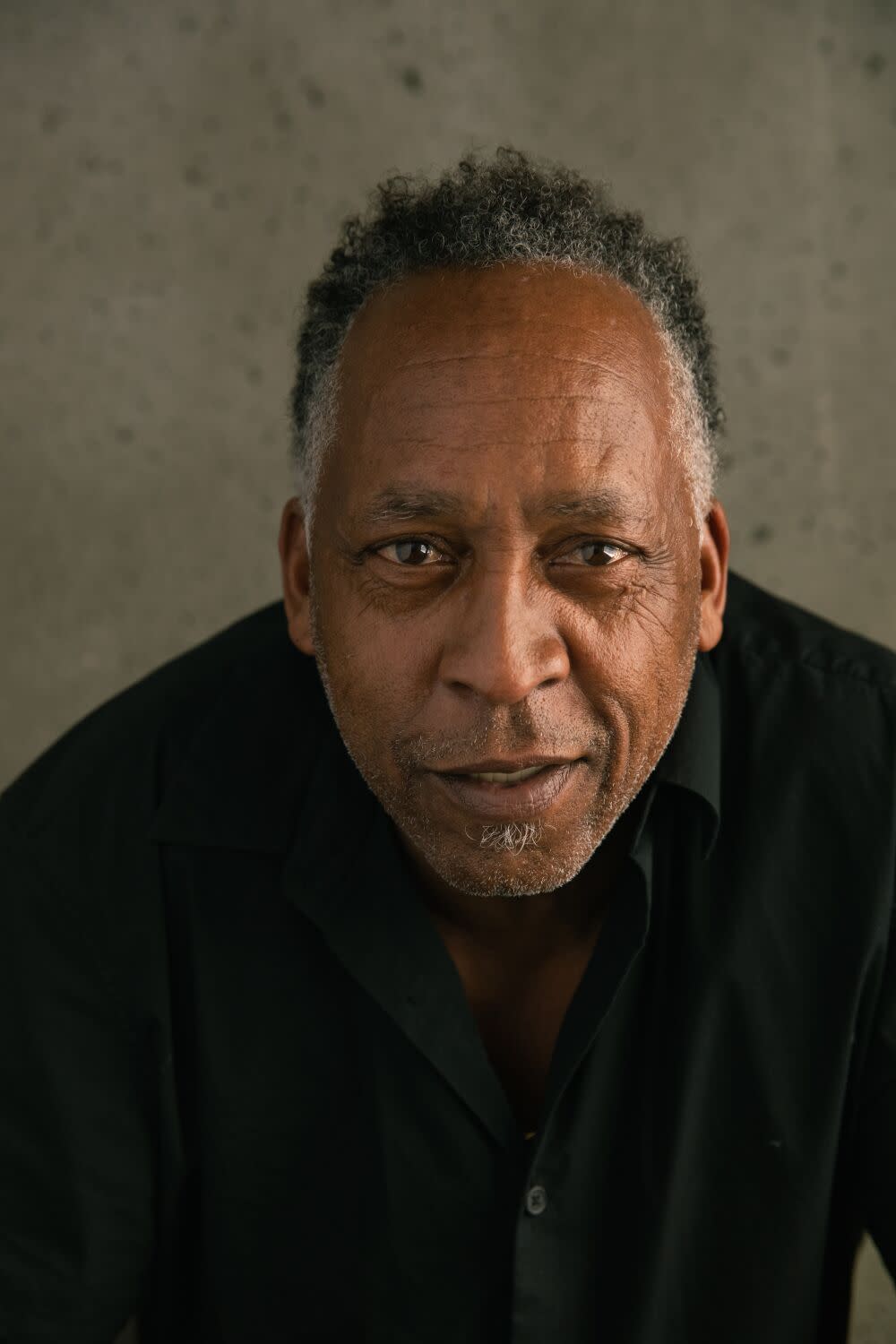

If you were to paint a portrait of Henry Taylor, you might start with his smile: brilliant, devilish, inhabiting both the mouth and the eyes.

My portrait of Taylor would start with his voice and its cadences. Taylor gets gravelly when he wants to confide but can pierce a crowded room with a roaring "Girl! What's UP!?!" Words are drawn out for impact and expletives dispensed as tokens of admiration. Of 20th century abstractionist James Jarvaise and comic book artists Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, he declares: "Those motherf— can draw!"

Taylor's conversation can meander from Philip Guston's late work to that time he met Bob Marley backstage at a concert. Ideas come so quickly that he cuts them off with a refrain, "Know what I mean?" Hamza Walker, a curator who has known Taylor for a decade, says that if he were to create a portrait of the artist, he too would start with his words: "'Know What I Mean' — that's what I would call my portrait of Henry."

The best depictions of Taylor, however, are self-portraits. The Los Angeles painter, who is 64, makes regular appearances in his own work.

In a 2015 canvas titled "i'm yours," he carries the gaze of a worried parent as he stands in the company of his older children, Jade and Noah. In another, he scrutinizes Epic, his 2-year-old daughter with artist Liz Glynn, as she sits in a high chair — green peas dotting her bowl and the floor.

In a wry and elegant self-portrait painted last year, Taylor renders himself in royal robes, modeling a 400-year-old portrait of King Henry V of England that hangs at the National Portrait Gallery in London. The painting shows the artist in profile, his left hand effetely raised. It was inspired by a recent trip to England, when he spent a spell making work in the countryside.

Like many Taylor portraits, it touches on multiple themes: the legacies of British painting and the politics of representation. It also draws from his life. The youngest of eight children born to a house painter and a domestic worker living in Oxnard, Taylor likes to refer to himself as "Henry the Eighth."

In conversation, he offers it up with panache: "Henry THE EIGHTH!" he exclaims, brandishing a cigarette as if it were punctuation.

Taylor's kingly visage is the main promotional image for his new one-man show at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, appearing on street banners, the cover of the catalog and a billboard on the Sunset Strip.

Organized by MOCA senior curator Bennett Simpson, "Henry Taylor: B Side," which opened earlier this month, is the most extensive museum presentation of Taylor's work to date, bringing together almost four decades of work: paintings, drawings, sculptures, painted objects (such as the empty cigarette packs employed as diminutive canvases) and the sketches of patients he made when he worked as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital beginning in the ’80s.

The Camarillo drawings are clear-eyed, without a lick of sensationalism, and foreshadow the painter Taylor ultimately became: someone known for frank, empathetic renderings of people across social strata.

The artist is frequently dubbed a portraitist — famous for painting not just cultural leaders but also unhoused people he meets on the street — among them Emery Lambus, an L.A. street painter he has supported with art supplies and an exhibition. Two portraits of Lambus can be found in the show. (Also in the show: my portrait, which Taylor made in 2016, after I showed up at his loft to interview him for a story.)

To classify Taylor as purely a portraitist, however, is to leave out critical facets of his work.

In a painting by Taylor, you might find keen observations of the L.A. landscape, with its unforgiving light, low-rise architecture and tricked-out cars. You might run into historical figures such as Miles Davis and Cicely Tyson standing before the White House, in a work that smashes together places and times.

You will inevitably confront social forces. In several paintings, the forms of prison architecture loom on the horizon, a reminder of the carceral state's intrusions on Black life. In others, Taylor pays tribute to the ideas and aesthetics of the Black Panthers. One such work opens the MOCA show: a nearly 12-foot-tall canvas of his brother Randy, who helped establish a chapter of the Panthers in Ventura, standing before a spectral figure of an animal that could be a panther.

Elsewhere, art history itself is up for dissection. Paintings might riff directly on Picasso's bawdy "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" or Modigliani's languorous nudes; others make subtler allusions. A 2006 canvas titled "Fatty" shows a man standing before a corner market wielding a can of Olde English as if it were a royal orb — homie as Holy Roman Emperor.

"The word and idea of portraiture is very reductive," says Simpson of Taylor's work. "Henry is a real manipulator of imagery and materials. ... It's about gaps and remixing. It's about the merging of elements."

In his catalog essay, Simpson describes Taylor as "John Fante with a brush." Walker likes to call him "Cézanne from around the way."

Taylor, as a general rule, avoids wearing any labels other than painter.

…

Simpson says that if he were to make a portrait of Taylor, he would start with music. "There's always music playing in his studio," he says. "I'll come over and he'll put something on. We talk about music a lot."

When I land at Taylor's Arlington Heights studio on a sunny morning in October, he's been listening to South L.A. rapper G Perico. But he's less interested in talking about his musical tastes than in finding out what I've got on my playlist. We end up blaring salsa legend Eddie Palmieri's "La Libertad Lógica."

Music provided the guiding concept and title for Taylor's MOCA show. "B-side" traditionally refers to the flip side of an LP or a tape — the one that might receive less attention from the market or the critics. "Simon and Garfunkel might've said, 'Man, that song just came to me,'" he says. "Some things just come to you. The deep cuts, know what I mean?"

Taylor was born in Ventura and raised in Oxnard — "the 'Nard," as he calls it. His parents, Cora and Hershal Taylor, came to California from East Texas.

His earliest passion was not painting but journalism. "I won't throw away newspapers to this day," he says. "Even if they're tainted as f—. I want to turn every damn page." But he became interested in art through his friendship with the Hernandez brothers, who lived around the corner. "Those guys," he says, "are like Picassos."

Indeed, Taylor and the Hernandez brothers have cut parallel paths. The Hernandezes' beloved "Love and Rockets" comics are set amid Chicano punks in a fictional stand-in for Oxnard. Read the comics closely and occasionally you'll stumble into a frame that summons Taylor's paintings: figures caught in peculiar scenarios against backdrops redolent of Southern California.

Taylor's artistic turning point came under the tutelage of Jarvaise, a professor at Oxnard College. Jarvaise's work had appeared in the historic 1959 exhibition "16 Americans" at the Museum of Modern Art in New York alongside iconic conceptualists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Taylor was so taken with the elder's work that he kept retaking his class — until Jarvaise prodded him to attend CalArts.

At that point, Taylor was in his 30s, working as a tech at Camarillo State, the father of two small children. It was a punishing schedule — school in the morning, work at night, family life jammed in between — but he received his undergraduate degree in 1995. Before attending critiques at CalArts (which are famously merciless), he would take his paintings to Jarvaise for review.

"The things that he would see and comment on — the best crits I've ever been in," recalls Taylor. "If I could go back and relive certain things, I’d probably say my mother and a crit with Jarvaise. And I’d be taping that s—!"

The MOCA exhibition marks a bit of a homecoming. The artist's last solo museum show in L.A. was at the Santa Monica Museum of Art (now the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) in 2008. But some of his most career-defining exhibitions have been in New York — at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2007 and at MoMA PS1 in 2012.

It was at MoMA PS1 where I first encountered Taylor's work, which included an assemblage of broom handles and painted jugs that felt like it was tweaking early Modernism's obsessions with African statuary. (Imagine Brâncuși working with cleaning implements.)

When I pop into MOCA about 10 days before the exhibition opening, Taylor is at work on an even larger installation: a sculptural piece inspired by the Black Panthers featuring a squadron of mannequins in leather jackets, many donning buttons bearing images of Black people killed by police. The piece began as a nod to his brother Randy, the former Panther. At first he merely wanted to put a leather jacket in the show, he says. "And then the leather jacket became mannequins with jackets." That led to many more mannequins and drawings that have taken over the walls.

Artist Andrea Bowers has been friends with Taylor for decades. She says if she had to paint a portrait of Taylor, she would start with family — the root of so much of his work. "The work is so personal and so loving," she says. "And at the same time, it’s extremely political."

On the morning of my museum visit, Taylor isn't particularly inspired by politics. He wants to talk about painting. A conference room had been set aside for our meeting, but he prefers to hang out on Grand Avenue, where he can smoke. Standing on the sidewalk, he offers an impromptu discourse on the abstract landscapes of California painter Richard Diebenkorn and the riotous scenes produced by Beckmann, a German expressionist who also had a knack for revelatory self-portraiture.

"People make it about identity," he says of his own work. "But sometimes you are just painting. And that's more important than maybe the subject — the fact that you have this insatiable urge."

A woman interrupts Taylor's speech — a friend, jewelry designer Darlene de Sedle. He sings out her name: "Darlene!"

She has rings for him to don at his opening, including a black opal that sparkles in the sun. "Isn't that beautiful?" she exclaims.

"He is an Egyptian king to me," she says with a nod to Taylor.

The ring wouldn't be out of place in that self-portrait inspired by Henry V, the one printed on a large banner by MOCA's entrance. Taylor flashes a smile. It is good to be the king.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.