They make ‘the heart beat faster.’ How Idaho preserved Sawtooth mountains 50 years ago

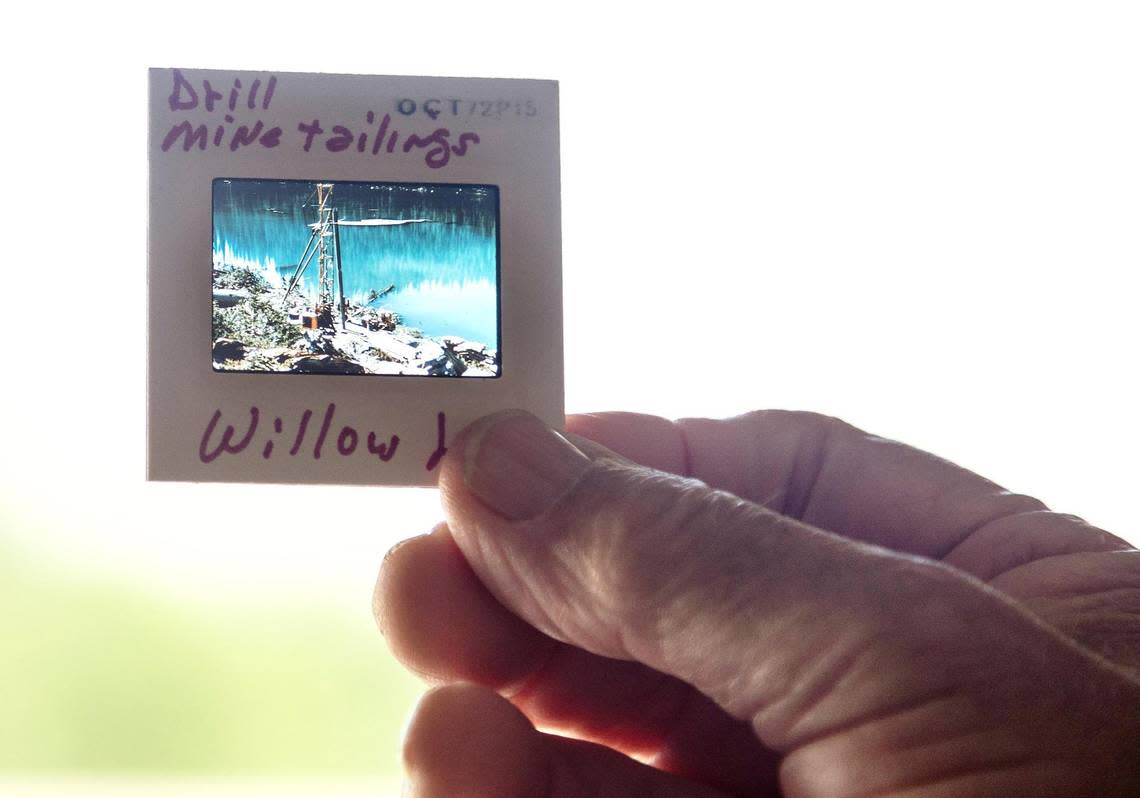

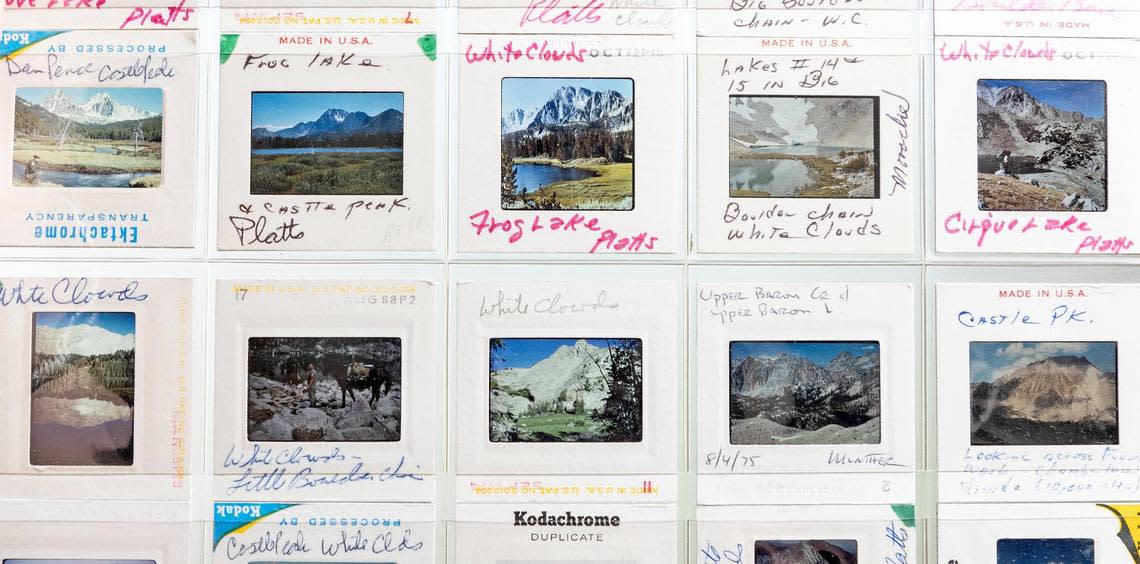

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Bill Platts’s job was to survey dozens of lakes in and around Central Idaho, examining their water quality and the suitability of their fish habitat.

One day in August 1969, while deep in the White Cloud Mountains, he heard a noise.

Arriving at Willow Lake, which is nestled in a wilderness of tall, rocky peaks, he saw an unwelcome sight: a drill outfit, flown in by helicopter, boring into the rock. The team had dug a ditch from the drill site and was pouring oils and effluent into the pristine alpine lake.

By 1969, much of the area in the White Clouds had been staked out by mining claims. A 19th century law had allowed Americans broad latitude to mine on public land.

For decades, environmental groups had pushed for greater protections for hundreds of thousands of acres of high-elevation, remote country in Central Idaho. But the fight over mining brought the issue to a head. It led to the formation of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, which marks its 50th anniversary this month.

That recreation area pitted state leaders against a growing environmental movement. It wound up in the halls of Congress as several proposals for a national park. And for half a century, it protected hundreds of thousands of acres of mountain wilderness.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, Bill Platts’s job was to survey dozens of lakes in and around Central Idaho, examining their water quality and the suitability of their fish habitat.

One day in August 1969, while deep in the White Cloud Mountains, he heard a noise.

Arriving at Willow Lake, which is nestled in a wilderness of tall, rocky peaks, he saw an unwelcome sight: a drill outfit, flown in by helicopter, boring into the rock. The team had dug a trench from the drill site and was pouring oils and effluent into the pristine alpine lake.

By 1969, much of the area in the White Clouds had been staked out by mining claims. A 19th century law had allowed Americans broad latitude to mine on public land.

For decades, environmental groups had pushed for greater protections for hundreds of thousands of acres of high-elevation, remote country in Central Idaho. But the fight over mining brought the issue to a head. It led to the formation of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, which marks its 50th anniversary this month.

That recreation area pitted state leaders against a growing environmental movement. It wound up in the halls of Congress as several proposals for a national park. And for half a century, it protected hundreds of thousands of acres of mountain wilderness.

At the end of the 19th century, the United States no longer had a “frontier.”

Native tribes, including those in the Sawtooth area, had been forcibly removed. Settlers spread across the continent, and had done widespread damage through logging. The U.S. Army had attempted to exterminate the American bison.

That led reformers to feel the need to rethink how Americans approached the natural environment, given the destruction humans were capable of.

“There’s a national sense among progressive reformers that we need to maybe engage in a different way of thinking, one that’s not just about exploitation, but one that could include conservation,” said Sara Dant, a professor of history at Weber State University.

The early 20th century saw the creation of the Forest Service and the Park Service — government agencies tasked with managing lands in the vast American landscape.

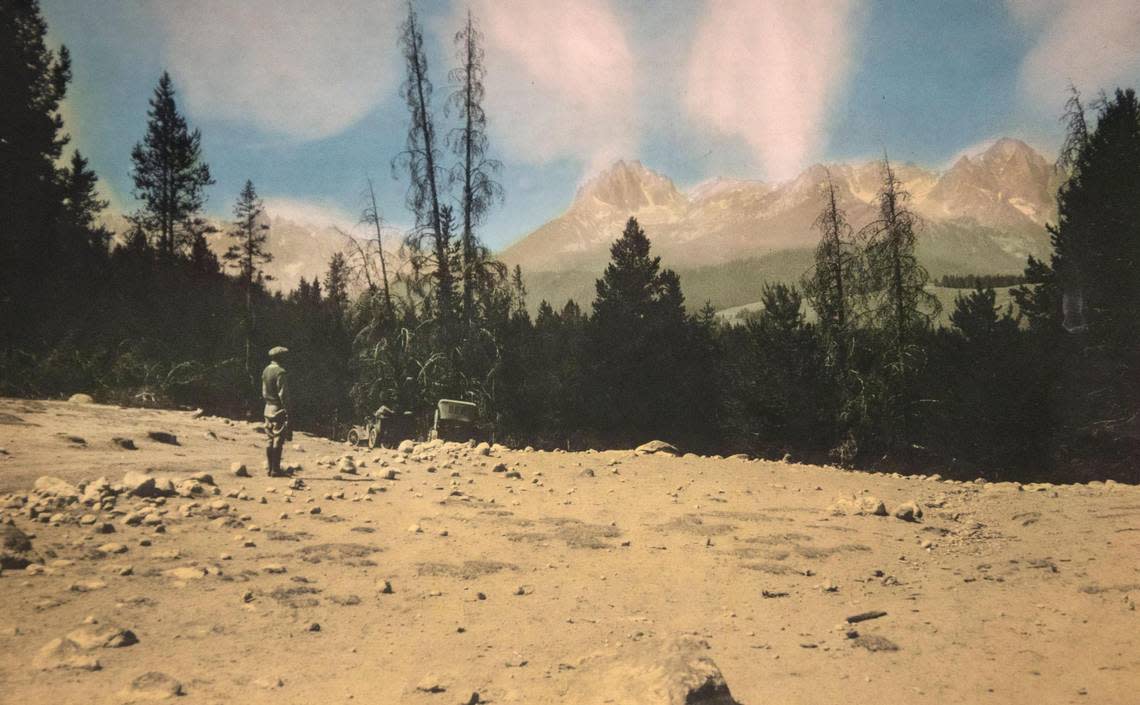

President Theodore Roosevelt first set aside the region of the Sawtooth Mountains as a Forest Reserve, and advocates for tourism wanted to draw visitors in. And as the Sawtooths gained recognition — Idaho included a model of the mountains in its 1915 World’s Fair exhibit — some advocates began to push for a national park.

“These are mountains that make the heart beat faster,” a 1911 Statesman article said.

But as enthusiasm for a park grew, so did its antagonists. Americans interested in using the nation’s resources, in mining, logging, and ranching, worried that the drive to protect landscape from development meant locking up the state’s resources, which until then had been the major draw of the West.

“When the federal government manages public lands, whether it’s doing so as a park, or a wilderness area, or recreation area, or even just (Bureau of Land Management) grazing areas, there are restrictions,” Dant said. Concerns arose that “if we create a park, it’s going to cut off access to potential wealth. … That’s a tug of war that still goes on.”

ASARCO mining

A rumor had spread. Something was happening in the White Clouds, a remote mountain wilderness near the Sawtooth Range.

Boyd Norton, then a research physicist at the Idaho National Laboratory, got a call informing him that a corporation was drilling around the mountain. Companies were searching for molybdenum, a sparkly element often used in steel production.

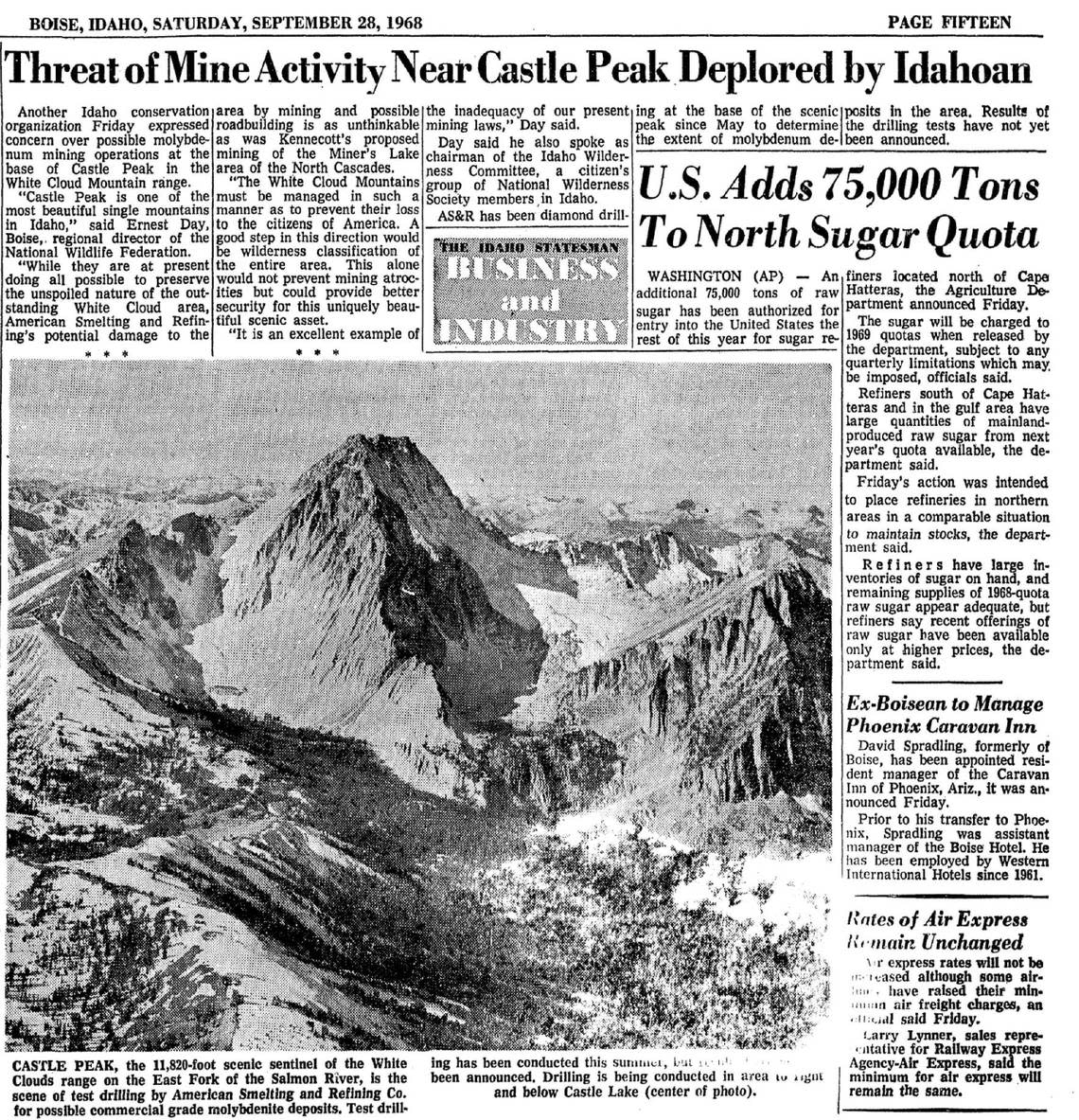

By September 1968, headlines in the Idaho Statesman declared a “threat of mine activity” near Castle Peak, the highest rocky peak in the White Clouds.

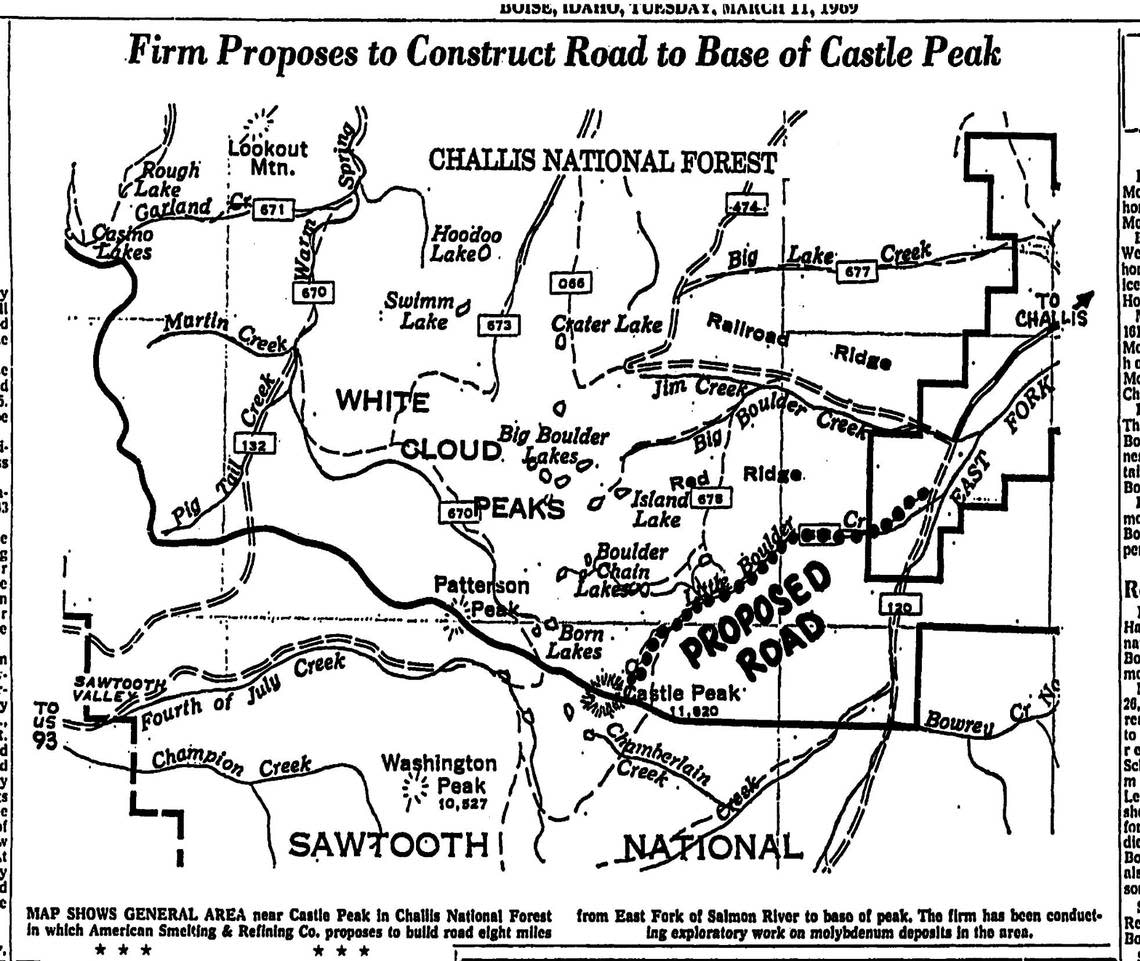

The American Smelting and Refining Co., known as ASARCO, had filed claims for several hundred acres in the White Clouds, while another company, Taylor Mining, had filed for several hundred more nearby, according to Norton’s book, “Snake Wilderness.” The open pit mine would require massive amounts of rock to be dug out of the mountain — up to 20,000 tons daily — and deposited in a tailings pond, to be created in a high-mountain meadow.

A fight was in store. Norton, who was living in Idaho Falls, had been part of a group called the Hells Canyon Preservation Council, which had fought to protect land along Idaho’s western border with Oregon.

That group — which had been founded by “about six people sitting in a living room drinking beer” — led into another, larger group, called the Greater Sawtooth Preservation Council, which was formed to fight the mining in the White Clouds. Around 23 people were part of its founding.

“We had to bring in a few cases of beer for that one,” Norton told the Statesman.

“When we started that Greater Sawtooth Preservation Council, we had a whole bunch of people who were ready and willing to sign up,” he said. “It’s a very special place,” he added, noting the area hosts the headwaters of the Salmon River and is a key fish run.

By May 1969, Frank Church, a third-term U.S. senator, had come out against the mine, arguing against “despoiling” “one of Idaho’s finest recreation areas,” according to previous Statesman reporting.

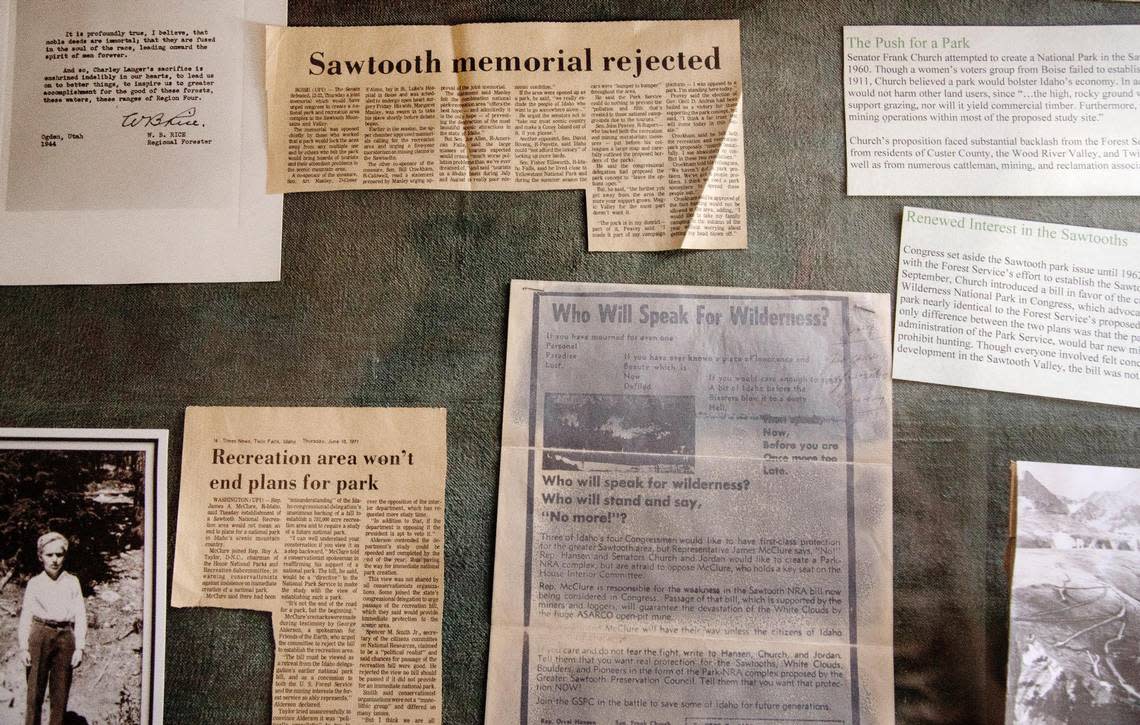

In Church’s 12 years in the Senate, he already had experience pushing for a national park in the Sawtooths, a contentious debate that pitted strict preservationists against Idahoans who wanted hunting, ranching and even private land to remain within its boundaries.

A national park or recreation area?

By the time Church started to explore the possibility of a park in 1960, the idea had been simmering for nearly 50 years. Just under 2 million acres of forest in the Sawtooths were set aside as a reserve in 1905, primarily to protect timber and agricultural interests, according to Statesman articles from the time.

The first mention of reserving the area as a national park came in 1900, after two Boise men visited Redfish Lake and called the area “one of the beautiful places that nature seems to have provided as a pleasure resort for man,” the Statesman reported. It wasn’t until 1911 that women’s social clubs began to formally advocate for a national park.

Rep. Burton French introduced a bill in Congress in early 1913 to set aside the national park. Two years later, the Idaho Legislature passed a joint resolution asking Congress to create a Sawtooth national park.

But the efforts continued to flounder. Once-widespread support for the park began to falter. In early 1916, the Idaho wool growers — including Gov. Brad Little’s grandfather, sheep rancher Andrew Little — passed a resolution objecting to a national park in the Sawtooths. The “sheepmen” appealed to Idaho’s congressmen to oppose the park, which they said would ignore livestock interests and potentially lead to an uptick in predators.

In March 1917, bills to establish a Sawtooth national park again died in Congress. A month later, the U.S. became involved in World War I, derailing the national park push.

For decades, legislation that cycled through Idaho’s congressional delegates continued to fail. In 1937, the Statesman reported that “opinion was almost unanimous that creation of the park would put a brake upon reasonable exploitation by miners, stockmen and lumbermen and would also hinder use as a playground.” The same year, the Secretary of Agriculture created a 200,000-acre Sawtooth Primitive Area.

In early 1966, with a sixth national park proposal set to expire in Congress, the National Park Service and Forest Service released a joint study that leaned heavily in favor of creating a national recreation area to be managed by the Forest Service. Church conceded that a national recreation area could be more suitable for Idaho’s needs and introduced bills for either option.

‘We cannot afford to destroy this high-altitude, alpine area’

With two proposals on the table — one for a national park and another for a national recreation area — interest groups in Idaho began to unify around the recreation area, which would maintain looser restrictions than a park.

Norton’s cohort initially pushed for a national park, and met with Sen. Church to discuss the options. Though Church himself had pushed for a park early on, that soon changed.

“Frank told us quite frankly, ‘You’re not going to get a national park,’” Norton said. “It’s not a popular thing in Idaho because so many sportsmen are against national parks because they don’t allow hunting.”

As public concern about mining in the White Clouds grew, Church and Sen. Len Jordan, who had co-sponsored the recreation area bill, amended it to include the White Clouds.

Idaho’s governor at the time, Don Samuelson, was opposed to protecting the area from mining, as were prominent business people like Jack Simplot, the founder of J. R. Simplot Co., according to Ken Robison’s book, “Defending Idaho’s Natural Heritage.” The issue became a defining aspect of the 1970 gubernatorial campaign, where Samuelson faced Democratic candidate Cecil Andrus.

“We cannot afford to destroy this high-altitude, alpine area to mine a low-grade, export ore for the temporary economic gain of a few,” Andrus wrote in a Statesman candidate questionnaire in November 1970.

Andrus defeated Samuelson later that month, with many attributing his victory to his position on preservation of the White Clouds.

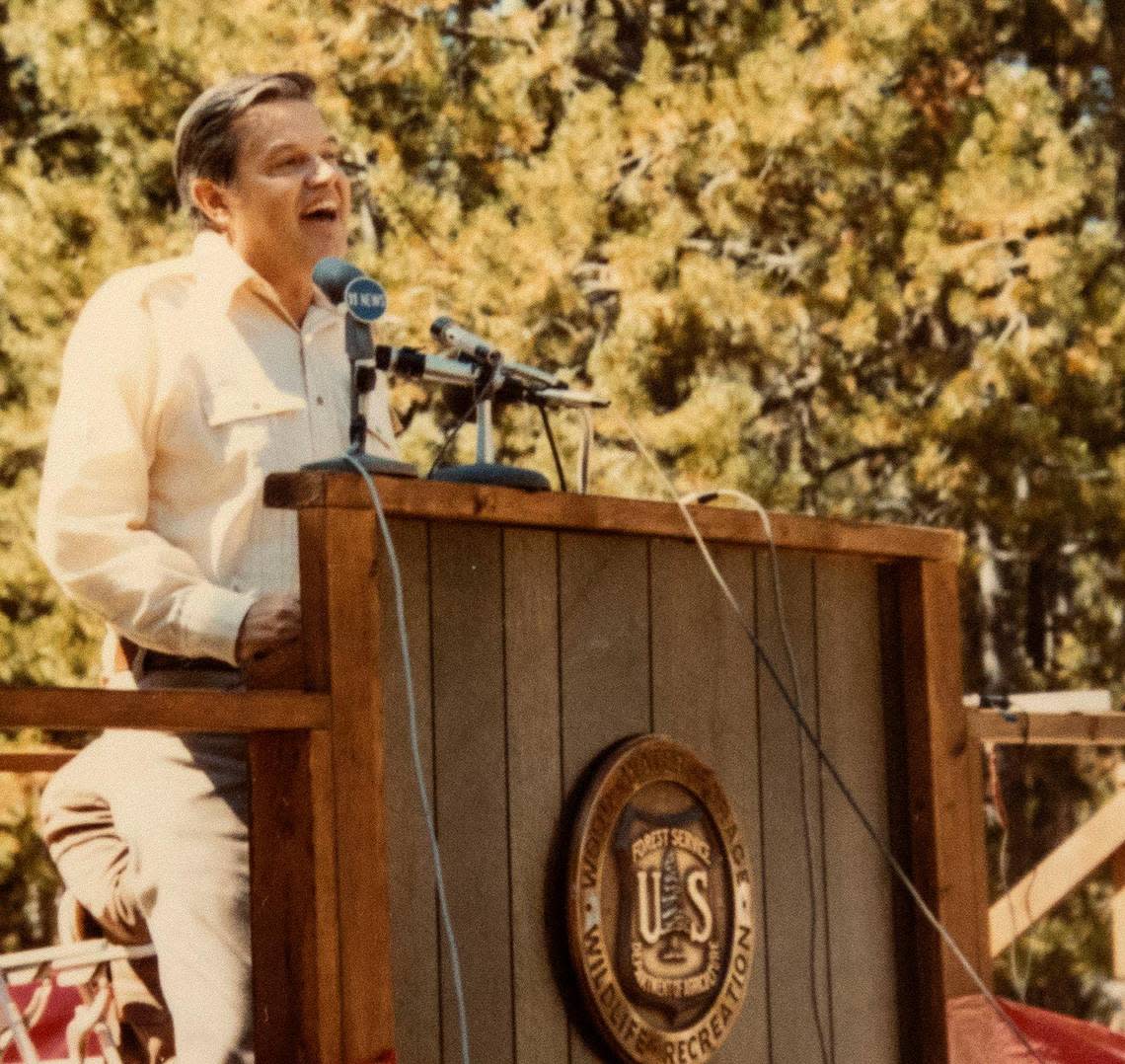

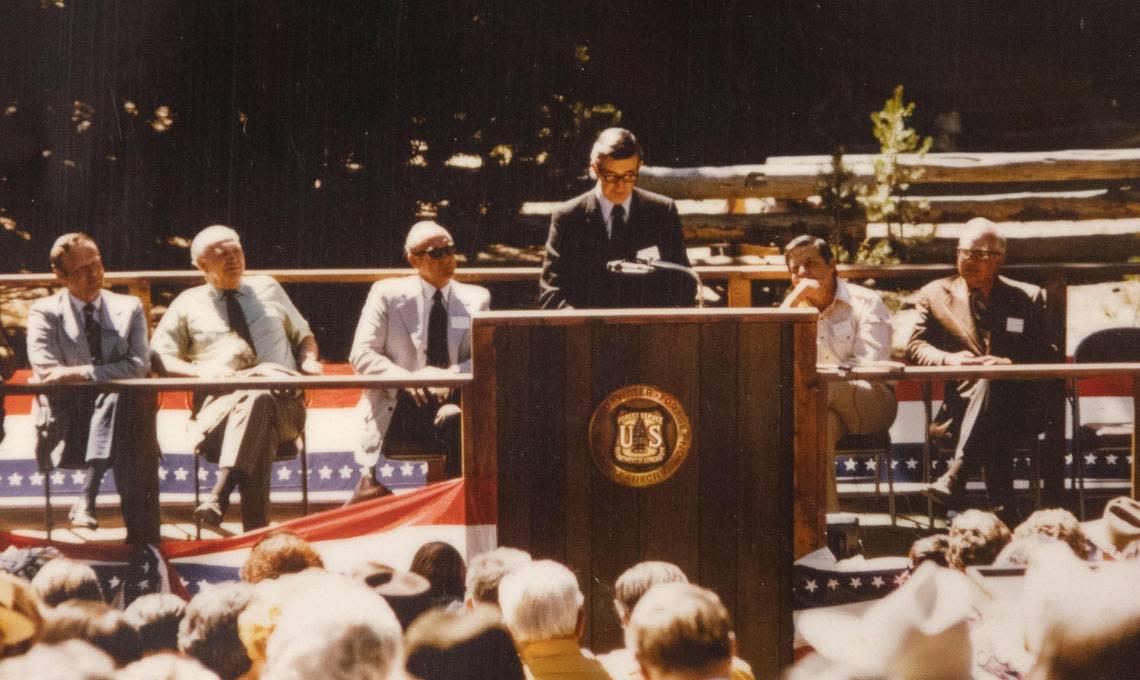

It then took the state’s entire congressional delegation to get a bill creating a recreation area through Congress, which happened in August 1972. The legislation, which was introduced by Reps. Orval Hansen and Jim McClure, established a recreation area with a wilderness area inside it, where motorized equipment would be banned.

“When you look back in history, you’re just glad we had people like Frank Church with a vision and the courage and really the legislative acumen to get things done,” said Larry LaRocco, a former Idaho representative who worked for Church for years.

The law also exempted the land within the recreation area from new mineral exploration, and provided rules for existing mining claims, Forest Service spokesperson Elizabeth Wharton said.

While earlier versions of the bill would have provided special use permits for mining companies to access their claims, Church removed that language from the final bill, Robison said.

“It looks like we lost that round,” a spokesperson for the Idaho Mining Association told the Statesman the summer the SNRA legislation became law. He added that the company would likely have trouble getting permission to build a road to the claims.

After activists had pushed for decades to protect the Sawtooths, it was a fight over mining in an adjacent mountain range that got the bill over the finish line.

Former SNRA backcountry manager Ed Cannady would later describe it as “a national park where people get to be part of the ecosystem.”

Multiple use: Mining, hunting and grazing

Though multiple use was a key part of the fight to create a recreation area, not a national park, the popularity of practices like mining and grazing has waned in the decades since the SNRA’s creation.

Today, only about 70 active mining claims remain, though SNRA area ranger Kirk Flannigan said only one is operational. Claimants must propose mining plans to the area ranger, who can reject them if they don’t meet stringent standards to preserve the environment and scenery. Annual maintenance fees are also required, and claims that are not maintained are forfeited.

Mining claims can, however, be passed to new owners, meaning the remaining claims could exist for years to come.

In the 1910s, when a park was first proposed, the Statesman reported that wool growers estimated between 12,000 and 15,000 sheep grazed in the areas proposed for a national park. By 1963, that number had decreased to about 9,600 sheep.

Today, Flannigan said, about 3,000 sheep graze on the SNRA, along with roughly 1,300 cattle. The decline has coincided with an overall downturn in ranching, as well as additional grazing closures in parts of the SNRA.

‘The threat of high-density development’

Though the 1972 law that created the SNRA set aside hundreds of thousands of acres as federal public land, portions of the region remained in private hands.

Settlements that pre-existed the recreation area, including the town of Stanley and ranches in the Sawtooth Valley, were allowed to remain as such. But the new law also authorized the secretary of agriculture to negotiate scenic easements with landowners, which would occupy the Forest Service in the coming decades.

While many in the public had been concerned about open-pit mining, Bob Hayes, former director of the Sawtooth Society, said that “the bigger cause for alarm was the threat of high-density development.” About 25,000 acres, or 3% of the total area, was private when Congress created the recreation area, Hayes said.

To head off development of land that would damage the “natural, scenic, historic, pastoral, and fish and wildlife values,” as the act stipulates, the law also provided the Forest Service with the authority to issue private land regulations that would designate what would and would not be allowed.

And if scenic easements failed, the Forest Service could condemn property, or seize it.

In the early years, the Forest Service acquired some of the largest parcels by buying them from the owners, Hayes said. They also purchased conservation easements on nearly 100 properties, which constitutes around 85% of the privately owned land in the area, he added.

“That is probably the single biggest reason why you can stand at Galena Summit, the overlook there, and gaze out at the Sawtooth Valley and see that it’s largely untouched from what it was in 1972,” Hayes told the Statesman.

In an area of the valley known as Obsidian, a developer wanted to build condominiums, which the Forest Service condemned in the early ’90s, said Terry Clark, a retired employee and vice president of the Sawtooth Interpretive and Historical Association. The developer was paid market value for the property.

In the mid-’90s, another property owner was in the process of trying to sell 15- to 20-acre lots for building, after bad blood had developed between the landowner and the Forest Service.

The Sawtooth Society worked with both parties to purchase easements on the property from the landowner, Hayes said, and to stop development there.

But in recent decades, the Forest Service has had less ability to purchase easements and stop potential development in the SNRA.

“In the late 1980s, (the Forest Service) ran out of money,” Hayes said. Funds for conservation easements come from the Land and Conservation Fund, which has been underfunded for decades.

That fund, which intended to designate money for conservation, was only fully funded twice since its passage in 1965, according to the New York Times. In 2020, President Donald Trump signed a law permanently funding the reserve with $900 million every year.

Some of the earliest easements in the SNRA don’t have as stringent requirements as more recent easements do, and therefore could still allow for more major development.

“Some of those easements are very old and they are kind of a handshake deal, said Kirk Flannigan, the SNRA area ranger. “And they don’t have a lot of teeth associated with them.”

In the last three years, as the draw of the Sawtooth region has grown, pursuing new easements has become even more difficult for the Forest Service.

“You need a willing seller, and we can’t pay fair market value. We cannot compete with the real estate market,” Flannigan said.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of visitors to the Sawtooths ballooned, and recent development has some locals concerned that some of the remaining private land could be developed in ways that do not preserve the values laid out in the original SNRA law.

The SNRA saw an 87% increase in visitors between 2015 and 2020, according to Forest Service data.

“I have some concerns lately,” Clark told the Statesman.

The law establishing the SNRA says that the “frontier character” of the West should be preserved.

“I look at this as an experiment. Is there something we can do to take care of this place without all the restrictions that national park status usually implies?” Clark said.

Speaking of new homes that have been built, Clark said that in “the last decade or so, I’ve been starting to see some things that I personally question whether or not we’re still meeting the Western ranch atmosphere that the legislation was trying to preserve.”

‘It’s our whole lifeline’

Platts didn’t know if he had authority to tell the drillers to cease. But he told them to, anyway.

After he saw the mining company drilling at Willow Lake, Bill Platts approached the operator, told him he was from the Forest Service, and asked him to shut down, fearing that bentonite, the material the drillers were pushing into the lake, would seal the bottom and kill the plants in the lake.

The operator got on the phone, and then told Platts he wouldn’t stop drilling.

Platts’s support for protecting the White Clouds could have — and nearly did — cost him his job. But he didn’t care.

“At that time I was determined to do everything I could for the White Clouds,” he said.

Angry, Platts drove to Pocatello days later and talked to an official with the state’s Department of Health and Welfare who had authority to enforce water quality violations. The two returned to the site, and again asked the operator to shut down.

Again, he said no, Platts said.

It wasn’t until the mining exploration in the White Clouds became more publicly known that the pollution of the lake stopped, Platts said.

“The grassroots now … had the power,” he told the Statesman. “They completely took the power away from ASARCO and the Taylor group.”

ASARCO, now owned by Grupo México, did not respond to requests for comment. Attempts to locate Taylor Mining were unsuccessful. Custer County records indicate that a principal of the company, Vernon Taylor III, sold claims to another company in the ’80s.

Platts said it was the Forest Service’s decision to delay approval of a road while further environmental studies were performed, the pressure by conservationists, and the low price of molybdenum at the time eventually stopped the mining projects.

After over a half-century of efforts to protect the Sawtooth region, it was the potential for mining and the ecological damage it would bring that galvanized public support and marshaled the political will needed to pass a bill.

Now 93, Platts said that the high-elevation cold streams in the Sawtooths and White Clouds are essential fish habitat, as dams have constricted fish’s ability to spawn and climate change warms water temperatures.

“Something we haven’t really gotten across to the public is how valuable water quality is in the high country,” he said. “It’s our whole lifeline.”

Photos and videos were taken by Sarah Miller, visuals customization created by Clay Jones.