Before freeing convicted killer, SC judge reduced another man’s life sentence. Was it legal?

The Richland County judge and solicitor under scrutiny for their roles in the secretive release of a convicted murderer used questionable legal means to reduce another man’s mandatory life sentence, a review by The State Media Co has found.

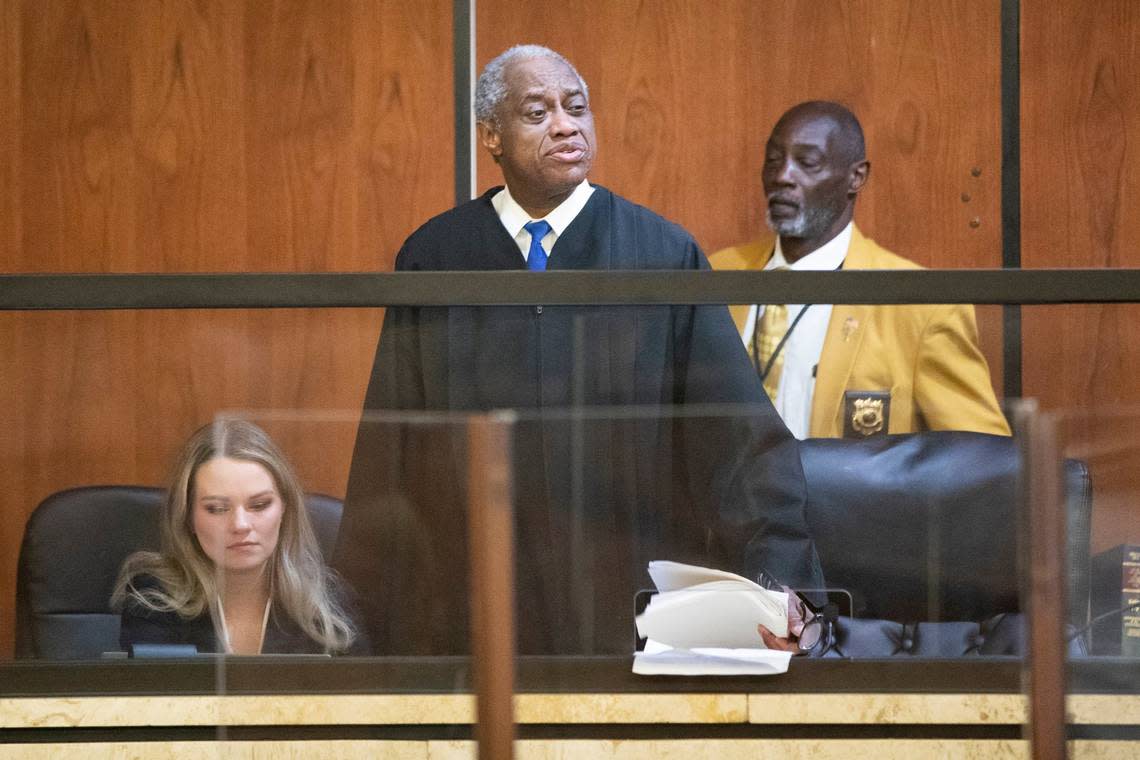

Nine months before now-retired Circuit Court Judge Casey Manning signed an order freeing convicted killer Jeriod Price this past December, he spared a 48-year-old Columbia man at the request of 5th Circuit Solicitor Byron Gipson.

Manning’s order, which reduced Lahborn Allah’s sentence from life without parole to 30 years, cites no legal rationale and does not appear to conform with state law, according to legal experts interviewed by The State.

Allah, who has been locked up since 2000 on first-degree burglary charges, is now projected for release in 2026, according to prison records.

Gipson said Allah’s sentence was reduced “based on what justice requires.”

“I’m the solicitor in this case and it’s my job to make sure that justice is done,” he said. “I’m not aware of a statute that says I cannot do this.”

When asked to cite a statute that permitted him to reduce Allah’s sentence, Gipson responded: “That’s my statement. I’m not aware of a statute that says I can’t do it.”

Manning could not be reached for comment.

The case is one of at least 27 criminal sentence reductions granted statewide since 2022 now under review by the South Carolina Attorney General’s office. Attorney General spokesman Robert Kittle said the office is reviewing the reductions to ensure they were done transparently and according to law, but declined to comment on specific cases.

The state Department of Corrections compiled the list of sentence reductions at Gov. Henry McMaster’s request in response to Price’s controversial release earlier this year.

The convicted murderer, whose attorney is House Minority Leader Todd Rutherford, D-Richland, was quietly freed in mid-March after serving 19 years of a 35-year sentence. Manning signed off on Price’s release one day before retiring from the bench last December.

The South Carolina Supreme Court vacated the judge’s order April 26, and directed law enforcement officials to return Price to prison immediately. He has yet to surrender and remains at large.

Unlike the order granting Price’s release, which was executed behind closed doors without the victims’ knowledge and sealed from public view, Allah’s sentence reduction was carried out more transparently.

The victim, motivated by a desire to see Allah afforded another chance, wrote the solicitor’s office at S.C. Rep. Seth Rose’s suggestion and later met with Gipson to discuss the case. Gipson brought the case to Manning, who heard it in open court.

Rose, a criminal defense attorney, vehemently defended the proceedings and said he was extremely proud of the “very small role” he played in them.

“What was done here was appropriate,” said Rose, who worked with Allah’s family and connected the victim to Gipson’s office, but did not formally represent him. “Everything was done above board.”

He said Allah’s life sentence, handed down as a result of the state’s two-strike life without parole law, was “absolutely unconscionable” and that he felt compelled to help as a result.

“The only reason I was involved was because the more I looked at this, the more I was like, this is wrong,” he said. “Why would we have this kid do life when the victim himself never wanted this?”

Legal experts contacted by The State newspaper were sympathetic to the parties’ desire to reduce Allah’s sentence, but said they’d never heard of a criminal sentence being reduced by consent, as happened in this case.

Consent orders are issued when all parties reach a voluntary agreement to settle a dispute. They are far more common in civil cases, but may also be reached in criminal cases, generally on procedural matters, said Gary Clary, a former South Carolina Circuit Court judge.

“If you are in the purest sense correcting an injustice that all of those proper parties agree occurred … it’s hard to say that shouldn’t occur,” veteran Columbia defense attorney Joe McCulloch said, speaking generally. “However, I think that our courts, which oftentimes hew to technicalities, might take a dim view of that.”

First Circuit Solicitor David Pascoe, who prosecuted Allah on unrelated drug trafficking charges shortly before his 2002 burglary conviction, said Manning had no legal authority to reduce Allah’s mandatory life sentence.

“It’s doable, but that doesn’t mean it’s lawful,” he said. “And the question is: are we going to do things the right way in our state or like this?”

A life sentence for burglary

Tyrone Ray had drifted off to sleep while watching TV with his young son at their Eastover mobile home on April 24, 2000, when he awoke to a knock on the screen door.

He walked to the door, still half-asleep, and was met by two men who brandished guns and pushed their way inside the house.

The commotion roused his 10-year-old son, who screamed as the men beat Ray to the ground with their guns and demanded money. A violent struggle ensued, as the frightened boy ran frantically around the living room.

Then one of the men grabbed the child and held a gun to his head.

Ray froze. He begged the men to release the child and said he’d give them anything they wanted.

The robbers tied his hands and legs together behind his back, crab-style, and dragged him into the bedroom, where he kept a pouch with cash. They placed a pillowcase and bed sheet over his head and told him they were going to kill him.

Ray asked them not to do it in front of his son.

Just then, he heard a door slam. He called for his son, but got no response.

The men had fled with $1,800, two guns, some jewelry and the young boy.

The pair, later identified as Lahborn Allah and Roy George Wilson, released the child a short distance down the road. He was traumatized, but not physically harmed.

The incident scarred Ray emotionally as well. More than 20 years later, he still inspects his house for burglars when he enters, keeps an eye on passing cars and gets uneasy when someone stands behind him.

“It laid a big impact on me because I was just getting my life pretty much in order,” said Ray, who recently spoke with The State newspaper about the break-in and his decision to forgive his captors.

At the time of the break-in, Ray was trying to get back on track after a stint in prison. He was newly married with a child on the way and had just bought the Eastover property with dreams of building a house on the land and starting a business.

After the burglary, Ray put his plans on hold and moved out of Eastover at his wife’s insistence, he said. His young son, whose custody he’d been trying to reclaim since his release from prison, was forced to move out of state and live with Ray’s mother.

“I lost it all,” he said.

Allah and Wilson were arrested a few weeks after the break-in and convicted of first-degree burglary, kidnapping, assault with intent to kill and weapons charges.

Wilson pled guilty to the charges and received a 23-year sentence. He has since been released from prison.

Allah was also offered a plea deal, but took the case to trial and was found guilty on all charges. Because he’d pled guilty to an armed robbery 11 years earlier, when he was a minor, the burglary conviction was considered his second “most serious offense” and prosecutors sought a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Over the past two decades, Allah has challenged his sentence numerous times on a variety of different grounds. Each time his efforts have been denied, including by Manning, who dismissed Allah’s most recent request for relief in October 2021, records show.

Allah’s reversal in fortune appears to have been set in motion several months earlier, when members of his family reached out to Ray and said they wanted to discuss the decades-old break-in.

Ray said he was skeptical initially, but after discussing it with his now-adult son, agreed to meet the family and told them he’d be willing to speak with Allah.

A short time later, the men were on the phone rehashing the fateful night their paths crossed more than two decades earlier. Allah apologized for his actions and asked how Ray and his son were doing. He said he wanted to make amends.

Ray said his son, now in his 30s with a wife, daughter and house of his own, gave him permission to forgive their attackers.

“He said if it was OK with me in my heart to let it go and forgive them, then it was OK with him,” Ray said. “So I made that decision.”

Allah’s family also introduced Ray to Rose, a Richland County lawyer-legislator who was helping them with his case.

Ray agreed to write a letter in support of Allah. He also met with Gipson about the case and asked the solicitor to show Allah mercy.

“A lot has happened in the past 20 years and I have found forgiveness in my heart,” Ray wrote in a letter to Richland County Deputy Solicitor April Sampson that was introduced as evidence at a March 3, 2022 hearing on Allah’s sentence reduction. “The Defendant deserved to be punished but I always felt a life sentence was too harsh for a young man in his early 20’s. After having been praying on it I know it’s the right thing to do.”

Ray said he has no regrets about advocating for Allah and believes he deserves a shot at redemption.

The only thing he said he asked of his attacker when the men spoke was that he give back to the community upon his release.

“Talk to younger kids in this world out in public,” Ray said he told him. “Give to the ones who really need it, who are going to be in the same situation and need that conversation.”

Was Allah’s sentence reduction legal?

Whether Allah’s sentence reduction was lawful is debatable, lawyers consulted by The State said.

Rose defended it vociferously, calling it a “shining example of how a sentence modification is done publicly under the statute.”

“You can do anything by consent,” he said.

Lisa Catalanotto, executive director of the South Carolina Commission on Prosecution Coordination, the state agency that provides solicitors and their staff legal education and assistance, said it isn’t that simple.

A judge in South Carolina may only amend a sentence under three circumstances, she explained, citing the appropriate legal provisions.

“There is no specific law that grants authority to change a sentence outside of the above provisions just because both parties agree,” Catalanotto wrote in an email. “The SCCPC has not provided any advice to the solicitors about how to handle such a scenario and we have not been asked by the solicitors for such advice.”

Manning’s order does not cite any of the relevant provisions and, by Rose’s admission, did not follow them.

Other criminal defense attorneys consulted by The State newspaper who were amenable to Rose’s argument said the question of jurisdiction — the legal right of a court to decide a given case — would be key in such a situation.

A court that learns of a potential legal injustice, especially one carried out decades earlier, cannot simply step in and correct it. In order to right the wrong, the court’s authority to decide the matter would need to be established, they said.

“It’s a technical problem, not necessarily a problem that begs for criticism,” said McCulloch, the veteran Columbia defense attorney.

He declined to weigh in specifically on Allah’s case, but said he believes lawyers should strive to right any injustices they spot.

“Wrongs, when they are discovered, should be corrected,” McCulloch said. “And when there’s not an explicit route to correct the wrong, lawyers get out the book and try to figure out if there’s a way to do it.”

Pascoe, the solicitor who prosecuted Allah in the early 2000s, said he’d love to correct some of the injustices he’s seen in his own circuit, but insists it should be done by the book.

“There are a lot of people in prison who don’t deserve to be there right now,” he said. “So if I have commutation or pardon powers, let me know, because I will start to use them.”

Pascoe said he’s currently working with the state Department of Corrections and the governor’s office to find a legal way to get a parole hearing for a man convicted of multiple armed robberies in the 1990s and sentenced to life without parole under the two-strike law.

The law permits people who meet certain age and health criteria or who “can produce evidence comprising the most extraordinary circumstances” to be paroled if the Department of Corrections and Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services sign off.

Pascoe contrasted his own approach to seeking justice for inmates to the route taken in Allah’s case, which he said “opens up a Pandora’s box.”

“If we’re going to do this for Lahborn Allah, then we need to line up and probably do this for a lot of inmates at the Department of Corrections,” Pascoe said. “Maybe we should reevaluate every defendant who was sentenced to life without parole under the two strikes law.”

Mechanisms for SC criminal sentence reduction

A judge cannot change a sentence (except during the same week as the original sentencing) unless there has been a request made to amend pursuant to one of the following:

Rule 29 of the South Carolina Rules of Criminal Procedure, which provides that a party has 10 days after a sentence is imposed to file a motion for reconsideration or one year from the time “newly discovered evidence” is found to make a motion related to reconsideration of a sentence.

South Carolina Code Section 17-25-65, which allows a defendant’s sentence to be reduced for providing “substantial assistance.” Substantial assistance can involve assisting in the investigation or prosecution of another person or aiding a Department of Corrections employee or volunteer who is in danger of being seriously injured or killed.

A post-conviction relief proceeding during which an applicant alleges there is an error in the sentence and the evidence supports such a finding.

Source: South Carolina Commission on Prosecution Coordination