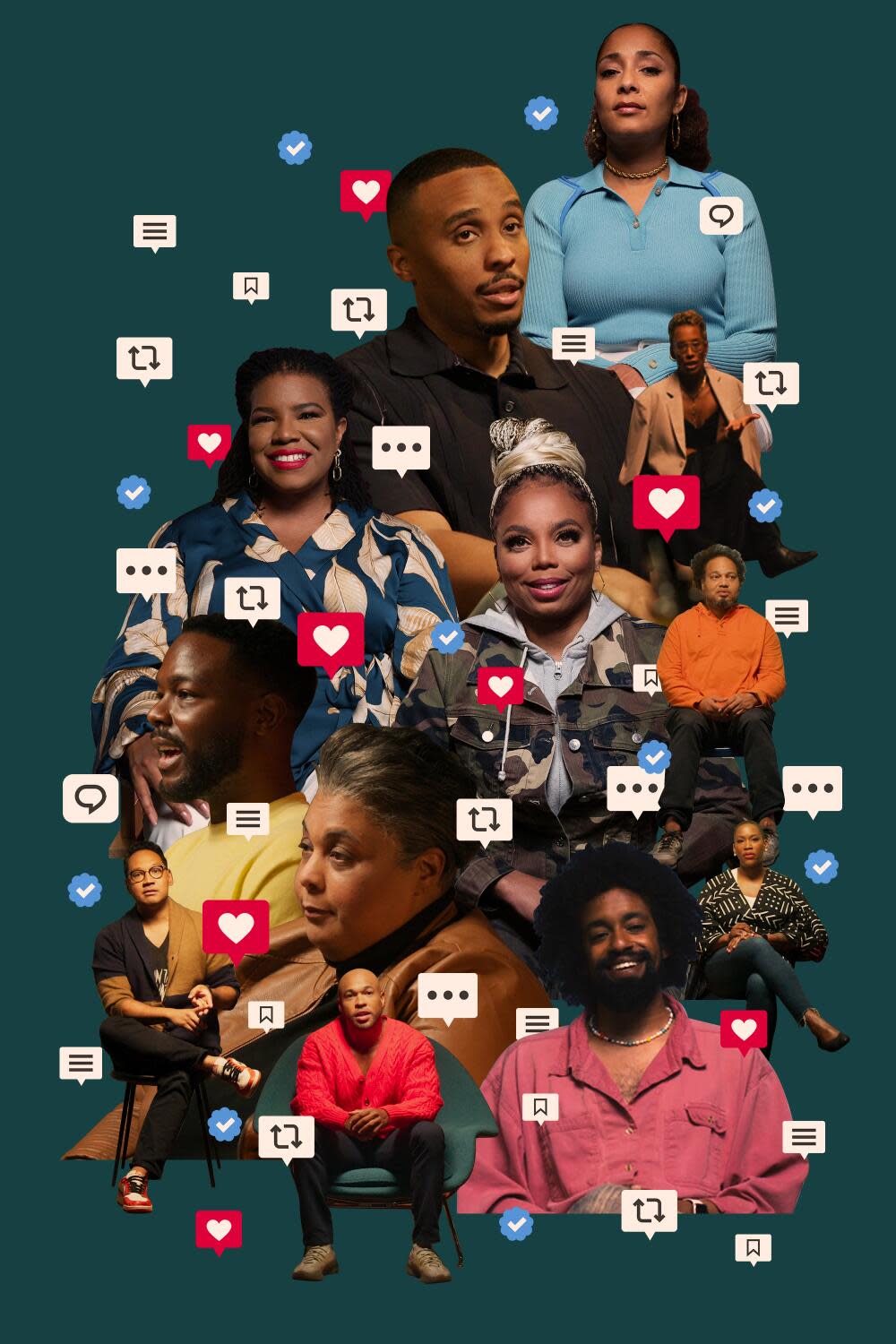

The free jazz ensemble known as Black Twitter, and how it became the subject of a new docuseries

Collective improvisation is a Black technology. It’s the root technique of most great Black music, dance, theater and performance, and the source of the charisma that has made Black Twitter worth its weight in data mining. A new docuseries on Hulu, “Black Twitter: A People’s History,” traces the path that the free jazz ensemble that is Black Twitter took in becoming an arbiter of cultural shifts time and again, a harbor of soft but insistent vigilantism. We improvise together there, hijacking what exploits us and sometimes even making it our muse or motivation; we do this for our pleasure, as hedonists, to fulfill our need to disassociate (as lumpenproletariat and cultural workers and bureaucrats and artists and students and saints and criminals). All demographics participate, though the elders sustain similar impulses on Facebook, now Meta, now metabolized by millennials and Gen Z into an antique or filial address book, a distant dystopia.

Read more:Arthur Jafa shifts into another realm

We congregate on Twitter (the documentary, like me, resists capitulation on calling it “X”) to address one another the way we might have if the whole world was a public high school hallway or backstage at the Apollo auditions or Birdland at the height of bebop’s fire, and we reside there with that exhilarated blend of familiarity, curiosity and tentative but cumulative trust that repeated public encounter builds. We divulge secrets we have nowhere else to vent, based on that good faith and trust, and scream into the crowded void there for clearing. Our avatars befriend one another and the likelihood that we will translate our tenuous though committed digital bonds into real life beyond Black Twitter is high-to-predestined.

We will shed that mimetic world of quick mundane prophecy, which initially and for several years limited us to 143 characters, and come offline together, eventually, singing protest memes in sync until they take on their lyrical personae and become the new temperament of Black protest music. 143 — a number that first earned significance as the late ’90s pager code for “I Love You.” And as Duke Ellington would say before announcing his ensembles at live concerts with his big band: “We do love you madly.” This could be the anthem animating the subconscious of Black Twitter, one of sublimated and disaffected affections .

“Black Twitter,” directed by Prentice Penny and based on Jason Parham’s 2021 series of articles for Wired magazine by the same title, details how the play and tension between expressions of love and expressions of madness and frustration have given the platform the universality of an epic tragedy or a farce, depending on the hour.

“Black Twitter,” directed by Prentice Penny and based on Jason Parham’s 2021 series of articles for Wired magazine by the same title, details how the play and tension between expressions of love and expressions of madness and frustration have given the platform the universality of an epic tragedy or a farce, depending on the hour. With the help of talking heads that also figure into the Black Twitter ecosystem — J. Wortham, Amanda Seales, Parham himself — we rehash the countless scandals and glories that have played out almost interchangeably on the app for the past 15 years and counting. One day we madly love Solange, Beyoncé, Renaissance and the halftime show. The next, we despise celebrities, love outlaws, militants and misfits, and reject grifters like Shaun King and Michael Rapaport, both of whom have used Black culture opportunistically and talk too unabashedly on Twitter. We listen to newly released albums and watch awards ceremonies as an ensemble, feigning authority over the careers of depraved celebrities, sometimes earning that power to cancel, at least briefly, perhaps to everyone’s detriment. As T.S. Eliot almost named “The Waste Land” (and Twitter is that), we do the police in different voices.

Read more:When did Black American music become an out-of-reach luxury?

All of the vitriol accumulated from not being heard in any meaningful capacity for most of our tenure as a diaspora, or not being acknowledged unless what we represent is expedient at the moment, arrives on Black Twitter as revenge, enacted through conversation that almost seems casual until you realize there’s strategy involved. The goal: invent a world wherein it’s shameful to be phony and aloof, and glorious to be candid and slightly messianic, in a chill social way. The platform within a platform has made the formerly antisocial and taboo conversations we used to have among ourselves, or refrain from instigating altogether, mandatory rites of passage for real and just social acceptance.

As the series reminisces, entire days in this territory with fluid borders are dedicated to apocryphal events like “negro solstice,” where thousands of avid Black Twitter users decided to claim that we were inheriting superpowers from the sun’s new phase of alignment on 12.21.21. The collective superstitions of Black Twitter would inspire a Stevie Wonder sequel, though they are born of play, desire and ritualized escapism. And there are the mass requiems, when Cicely Tyson died, when Aretha Franklin died, when Michael K. Williams died, when Harry Belafonte died, when there were riots going on after public killings, when Sly Stone reappeared with an autobiography and got some of his masters back in court, when Ye tweeted “everybody knows Get Out is about me” and made the Sunken Place a kind of headquarters for those too famous to be traced back to their civilian lives. On such days, the app becomes an archive of the simultaneous jubilation and sorrow that sometimes over-determines Black life. We are good at making the terrible and terror-driven beautiful, and the internet is a beautiful, terrible place; we’ve made Black Twitter its temple bar.

Read more:What can friendship teach you about the experiences of jazz in New York and L.A.?

If we were paranoid, we’d accuse the app of being invented by the CIA to study Black people who could not resist one another and had to invent this digital army band. However, collective improvisation only survives as long as real love is present, which allows for this space of ritualized sharing and bonding over insinuations and whispers to evolve into a grammar and linguistic encoding that cannot be breached by anything less than love. A part of me is territorial and doesn’t want to see this slice of the internet oversimplified and televised for all or turned into a party people long to get into, instead of a rehearsal for a new way of life. The docuseries, thorough and caring in examining its subject, also seems to mark an afterlife by telling our secrets to what will surely be a largely white, liberal audience seeking to understand why we have so much fun over there where they can’t come except as voyeurs or to appropriate.

The docuseries, thorough and caring in examining its subject, also seems to mark an afterlife by telling our secrets to what will surely be a largely white, liberal audience seeking to understand why we have so much fun over there where they can’t come except as voyeurs or to appropriate.

The series calls itself a people’s history but targets an academic sensibility, perhaps marking Black Twitter’s descent into the hypothetical footnotes of Black studies and critical theory where training and research can outweigh or override participation. Even jazz went this way, and hip-hop too is on its way into a form better studied than practiced, with its DJs selling their records to Cornel West instead of the club or local community. And regardless, it’s Black X now, not necessarily in the Malcolm sense but in the more fatuous identity crisis sense. There are cliques within cliques on Black X, many too obtuse or too Black for Hulu (which might be what rescues them and what’s left of the app’s joy and creative freedom from the studies industrial complex). It’s bittersweet to be historicized while alive and the series seems to realize this as it goes forth and tries, nonetheless.

I’m reminded of a meme that likely began in the dialectic of Black tweeting: Black people will never be lonely; there will always be a white person all in their business. The series is effective at preempting the intrusion of the white gaze or white-spirited spectator, explaining Black Twitter in a language the nosey can understand, so they will feel they aren’t missing anything after watching it and go off and mind their business. Let us be lonely on Black X and that the Black American Twitter dream may live, wherein one day we share Langston Hughes’ FBI file and the next day we trade takes on the Young Thug trial. It should be noted that the series is predominantly American, not in an effort to erase the rest of the diaspora but because Black Americans have perhaps insisted on making the app as outrageous as it is.

Syncopation is an advanced stage of sustained collective improvisation, which is maybe where Black X has to get to. It means that some can join in the style of Charlie Parker at Birdland, and never be deterred by anyone imitating Stan Kenton; some can take Drake’s side in the rap beef, some can take Kendrick’s, and some can ignore them both and follow the student insurrections they say nothing about; some live-Tweeted the Met Gala outfits, and some were more interested in the protests outside the Met; and when OJ Simpson died, I went to read his final tweet before looking for an obituary. It’s OK that the living and breathing digital archive of our fantasies is also an archive of our perversions and failures. It’s a sign we’ve survived both.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.