‘Forever chemicals’ have caused U.S. farmers to destroy cattle. What’s the threat in SC?

Art Schaap learned in 2018 that a military base near his farm had contaminated the groundwater he depended on to sustain his cattle herd.

Government tests found high levels of toxic forever chemicals in the water of his New Mexico farm and in the milk his dairy cows were producing. Because of the hazard, Schaap was forced to curtail milk production, euthanize more than 3,600 cows and bury the animals, he said this past week.

“We had to put them on site because it’s a hazardous waste and you can’t just bring them to a landfill,’’ Schaap said during a news conference highlighting the plight of farmers who’ve encountered forever chemicals on their land and in their water.

The news conference in Michigan was held a long way from South Carolina, but it focused on an issue of increasing interest in the Palmetto State:

How toxic forever chemicals are affecting crops and cattle in agricultural communities. The question is whether South Carolina farmers could suffer the same consequences of tainted crops and livestock that farmers elsewhere have.

So far, testing in South Carolina has confirmed forever chemical pollution in the soil and groundwater of hundreds of acres of farmland in Darlington County, about 75 miles east of Columbia.

In some cases, sewer sludge from an industrial plant was given to unsuspecting farmers as fertilizer years ago. Today, the groundwater used to irrigate crops and provide drinking water on the farms has shown elevated levels of the same types of forever chemicals that were in the sludge.

Across South Carolina, state regulators have approved spreading sludge on about 3,500 agricultural fields and 80,000 acres, The State newspaper and McClatchy reported in a recent investigative series.

While some of the sludge contained forever chemicals, information remains elusive about the extent of contamination on crops or in cows milk in Darlington and other counties where sludge was applied to agricultural land.

Little research is known to have been done in South Carolina on whether forever chemicals have worked their way into both crops and livestock from sewer sludge — or from leaks at military bases, as occurred on Schaap’s land in New Mexico.

Despite questions in South Carolina about whether PFAS is tainting crops, the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control says testing crops and milk isn’t its responsibility. The S.C. Department of Agriculture says it is not testing.

Once supported by government agencies as a low-cost fertilizer, sludge is of increasing concern nationally because forever chemicals are showing up in the gunky waste in multiple states.

Forever chemicals from polluted groundwater on military bases also are a threat to farms, crops and livestock.

The U.S. Department of Defense has notified more than 190 farms within one mile of South Carolina military installations that the farms are at risk from forever chemicals found on the military sites.

Levels of forever chemicals are in some cases thousands of times higher than a proposed new federal standard of 4 parts per trillion in drinking water, according to special Defense Department reports on the issue.

Military installations with pollution near farms include Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter, McEntire Joint National Guard Base in Richland County near Columbia, the now closed Myrtle Beach Air Force Base, and the Marine Corps Air Station at Beaufort, the Defense Department has reported in the past three years. Mobile home parks near Shaw have previously shown elevated forever chemical levels in well water.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the bases have contaminated farms, but it’s a question that needs answers, say those following the issue. The federal reports look at farms near military bases across the United States, including those in South Carolina.

Researchers in some other states have tested crops and milk for signs of forever chemical contamination.

The University of Maine, for instance, is specifically looking at whether crops on highly contaminated land are drawing in the chemicals.

Some research suggests that leafy vegetables, such as lettuce and kale, are more likely to contain measurable levels than vegetables that produce fruits, like tomatoes and corn, the Bangor (Maine) Daily News reported. But at least one study, conducted by a researcher at Michigan State University, found that squash also has wound up with elevated levels of forever chemicals.

Cattle from one Michigan farm were found to have elevated levels of forever chemicals, the Guardian reported last year. The farm sold beef to schools and farmers markets, the news outlet reported.

That’s notable because forever chemicals can cause certain forms of cancer, thyroid problems, high cholesterol and weakened immune systems. Used in everything from firefighting foam at military bases to non-stick frying pans and waterproof clothing, forever chemicals have been around since the 1940s.

They are formally known as per and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, but are commonly called forever chemicals because they don’t break down easily in the environment.

Maine resident Adam Nordell, a one-time farmer whose property was polluted by forever chemicals, said research there has helped enlighten state agencies on what to do about the contamination.

Maine has banned the use of sewer sludge as a fertilizer, set safety limits for one key forever chemical in both milk and beef, and established a $60 million fund to help farmers whose property has been affected.

Maine’s rules, for instance, bar shipping any milk that has exceeded a limit of 210 parts per trillion for the forever chemical known as PFOS.

“Our state’s regulation is informed, certainly, by this research,’’ said Nordell, who now works for the advocacy group Defend our Health. “The research helps make our regulations more effective.’’

So far, regulators in South Carolina have tested rivers, lakes, fish and groundwater, finding PFAS virtually everywhere they looked. But they have not followed through on plans to limit forever chemicals in sewer sludge, nor have they advocated for a state drinking water standard.

The Department of Health and Environmental Control also acknowledged that it is not checking crops or cows’ milk for PFAS.

“DHEC doesn’t have oversight of crop or cattle production in the state,’’ the agency said in an email.

The agency said it doesn’t know enough about PFAS to say whether farmers should be concerned about crops and cattle, but said all potential sources of exposure should be studied to protect people and products from the chemicals.

DHEC’s email said the agency hopes to work with other agencies or universities to assess the impacts of forever chemicals in South Carolina. For now, DHEC says it is encouraging those who spread sludge to monitor for PFAS, although the agency says it cannot require that.

“Our staff are keeping abreast of what research studies from academia are also finding,’’ the agency said in an email. Those studies include a report from Michigan State University and one from the University of Maine’s Cooperative Extension.

Eva Moore, a spokeswoman for the S.C. Department of Agriculture, said her agency is not now doing any testing for forever chemicals, but it is hearing from farmers who want to stay apprised of the latest information.

”We’re staying engaged locally and nationally to help answer that,’’ she said in a text Thursday to The State.

South Carolina’s farm economy is not as large as in some places, but it still is important to the state. Agriculture and forestry account for 259,215 jobs and have a $51.8 billion annual economic impact, according to the S.C. Department of Agriculture.

The Agriculture Department has been in regular touch with DHEC about forever chemicals, Moore said in an email. Forever chemicals “are on farmers’ radar and our radar,’’ according to the email, which went on to say “there is also a lot we don’t know.”

Some research is being done on forever chemicals at Clemson University, including a recent graduate school thesis that indicated one type of PFAS compound had not caused “adverse effects” in mustard plants. But university spokespeople were not able this past week to say whether other work on PFAS in plants or milk is under way.

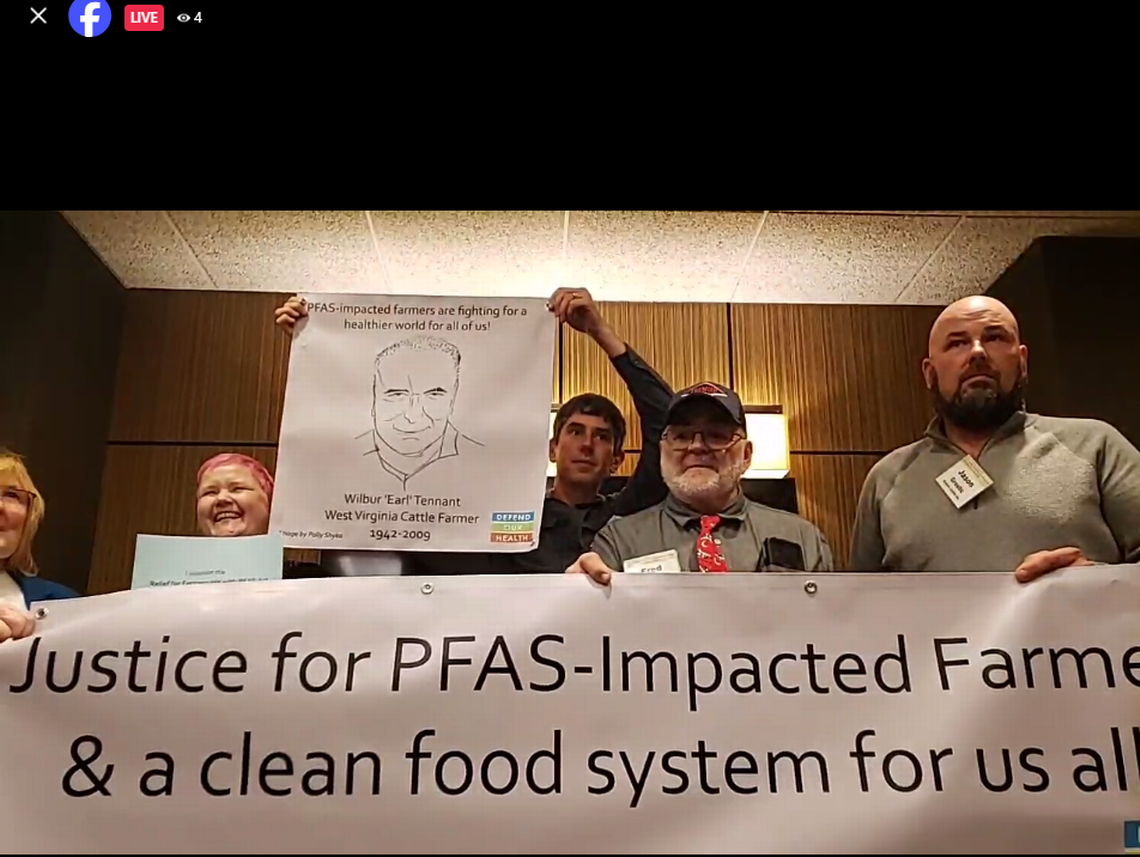

Schaap, the New Mexico farmer, was joined at Monday’s news conference by other farmers whose land and crops have been hurt by forever chemical contamination.

Among them was Fred Stone, a Maine farmer who gained national attention after PFAS contamination was found in cows milk at his dairy. It is suspected that sewer sludge he applied on his land years ago polluted the water. Sludge spread on the land had been championed as a low-cost way to fertilize crops.

Others included Michigan cattle farmer Jason Grostic, who said he needs help overcoming a problem that resulted through no fault of his own.

His 300-acre cattle farm was forced to shut down after state officials said PFAS had polluted water, feed and cattle, according to a story in The Progressive Farmer. That put him “100% out of business,’’ Grostic said during the news conference. He has had to sell his farm equipment to make ends meet.

The suspected cause was contaminated sewer sludge that had been spread on his land to help grow alfalfa and corn silage, a type of cattle feed. The sludge was considered safe when it was spread on the land.

“I’ve had my customers call me up and call me a murderer because I poisoned them,’’ Grostic said. “I didn’t poison them. I didn’t put this in my beef.’’

Those at the news conference said they support federal legislation to help farmers impacted by PFAS. In Grostic’s case, he said the state of Michigan has been of little help.

“They’re worthless,’’ he said.

The legislation now under consideration in Congress would provide money to states to help those whose crops have been affected.

Modeled after rules in Maine, the legislation would give aid to farmers to replace income lost by PFAS contamination of their land and crops.. Money also could be used to study the uptake of PFAS into farm products.

In addition, the legislation would provide money to help monitor people who have been exposed to PFAS on a farm. Out-of-pocket costs for monitoring are now outside many people’s budgets and blood tests for forever chemicals are sometimes not paid for by insurance.

Despite the federal effort, news conference organizers said it could be awhile before such legislation passes, assuming Congress approves the legislation.

“It is important for the federal government to step up, but as we all know, the federal government isn’t exactly the most speedy of bureaucracies, and it will take them time,’’ said Sarah Woodbury, director of advocacy for the environmental group Defend our Health.

For now, she said states need to take more aggressive action, similar to what has occurred in Maine.

“States need to step up,’’ Woodbury said.