Will Fetterman's victory change the way the media covers disabilities?

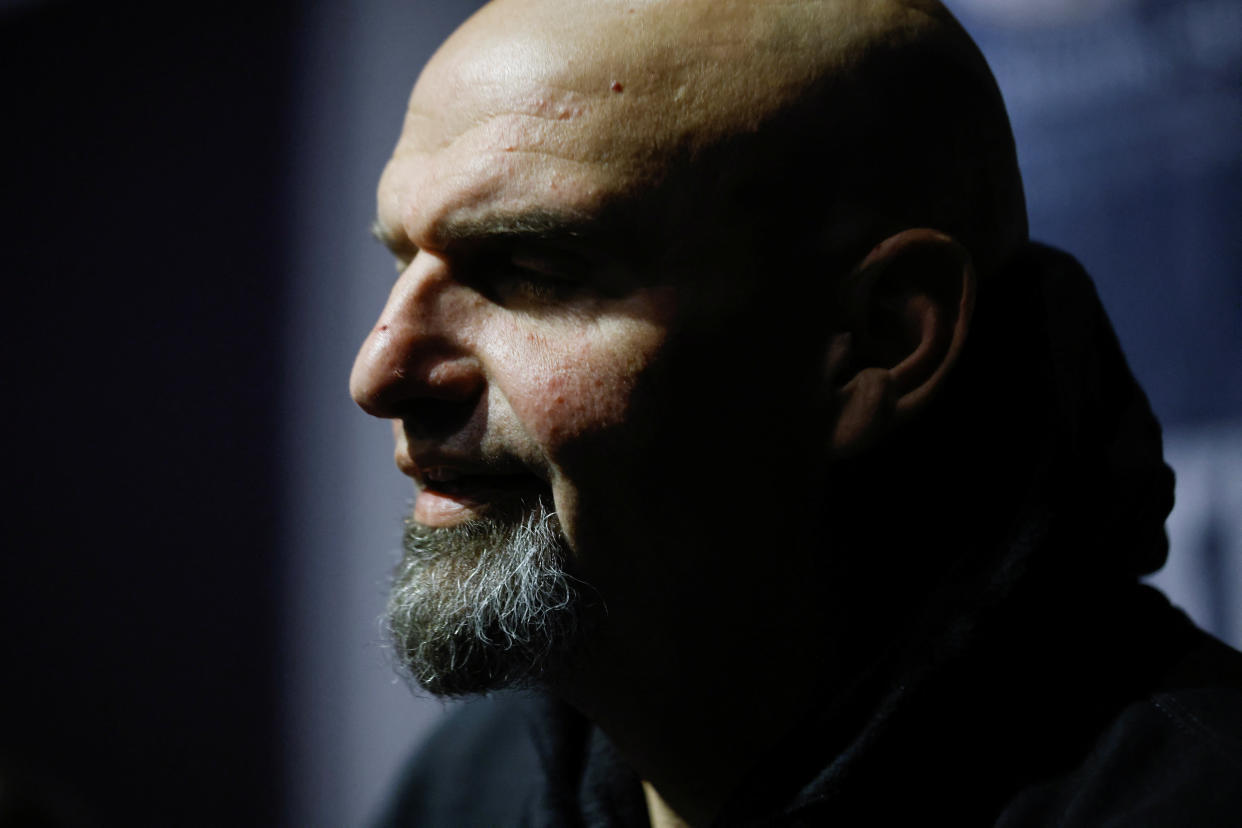

When John Fetterman, now Pennsylvania’s senator-elect, appeared in the race’s lone debate last month, he at times struggled with his speech. The Democratic lieutenant governor had suffered a stroke just before May’s primary, and although he returned to campaigning in August, he was suffering from auditory processing issues, meaning that while he was cognitively fine, he would occasionally miss words as he processed.

Fetterman had good days and bad days on the trail, and his debate against his Republican opponent, Dr. Mehmet Oz, was one of the tougher ones, even with screens to provide closed captioning for him. Many members of the media portrayed the event as potentially dooming the Democrat’s candidacy, with MSNBC host Joe Scarborough tweeting, “John Fetterman’s ability to communicate is seriously impaired. Pennsylvania voters will be talking about this obvious fact even if many in the media will not.”

Scarborough wasn’t alone, as others in prominent media positions called it “absolutely painful” to watch. Axios covered the evening with the headline “Fetterman’s painful debate,” including a number of anonymous quotes from Democrats, a recap of how the network that carried the debate talked about Fetterman negatively and a quote from retiring Republican Sen. Pat Toomey that was critical of the Democrat.

Politico’s Playbook newsletter began by noting, “We don’t usually dwell on a single debate,” before asserting that the “median voter in Pennsylvania is a middle-aged white person with a mid-five-figure salary who did not attend college” and might not be that familiar with the specifics of Fetterman’s condition. The publication did not note that many of those Pennsylvanians might know someone who had suffered a stroke or perhaps dealt with one themselves, living in a state where heart disease and stroke are the first- and fifth-leading causes of death, respectively, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national coverage tended to focus more on the aesthetics of Fetterman’s performance and less on the issues of the debate, which included Fetterman ducking a question on his changed position on fracking, and Oz sidestepping issues like the minimum wage, the questionable products he promoted on his syndicated talk show, and abortion, which ended up being a key issue in the election. In general, Pennsylvania outlets, from ABC’s Philadelphia station to newspaper front pages, spent far more time on the issues.

There were exceptions in national coverage. Two days after the debate, the Washington Post published a deeply reported piece on the potential difficulties for and misguided perceptions of candidates with disabilities. The Associated Press story on the debate included a section on how independent experts who watched the debate said Fetterman “appears to be recovering remarkably well.”

“In my opinion, he did very well,” Dr. Sonia Sheth, of Northwestern Medicine Marianjoy Rehabilitation Hospital in suburban Chicago, told the AP. “He had his stroke less than one year ago and will continue to recover over the next year. He had some errors in his responses, but overall he was able to formulate fluent, thoughtful answers.”

Despite such perspectives from medical experts complimenting his performance in the lens of his recovery, the headline of the piece was “Fetterman struggles in Senate debate against Oz after stroke.”

Darlene Williamson, president of the National Aphasia Association (aphasia is a disorder that affects speech), monitored Fetterman’s campaign closely. She told Yahoo News that in the aftermath of the debate she received “all kinds of positive feedback from our constituents. ‘I know how he feels, I know how difficult it is.’ And if it’s not difficult enough for people to go into a Starbucks and order a cup of coffee, imagine how difficult it is to get up on a national debate stage and hold it together.”

Williamson said it was important for Fetterman to show that his issue was “purely communication.”

“This is not cognition, this is not reasoning,” she said. “This is not any gap in any kind of intellectual functioning. This is 'I’m having difficulty translating incoming auditory content.' And I recognized a little bit of difficulty with the words that he used, and I loved his comment in the debate saying, ‘You might hear me mush up some words.’ That explains it exactly. So I think he was very direct, very upfront, very honest and very brave to do that.”

Williamson added that it was clear Fetterman was processing when he looked at the closed captioning, and likened his need for assistance to a person needing a cane.

“It’s like, ‘OK, yep, I got the question,’ which is just like using a cane,” she said. “‘OK, I’m gonna just use this cane to steady my leg.’ He was just using that monitor to steady his comprehension, and it’s obvious that it worked.”

Fetterman said his stroke was caused by “a clot from my heart being in an A-fib rhythm for too long,” and he underwent a procedure to have a pacemaker inserted on the day of the primary.

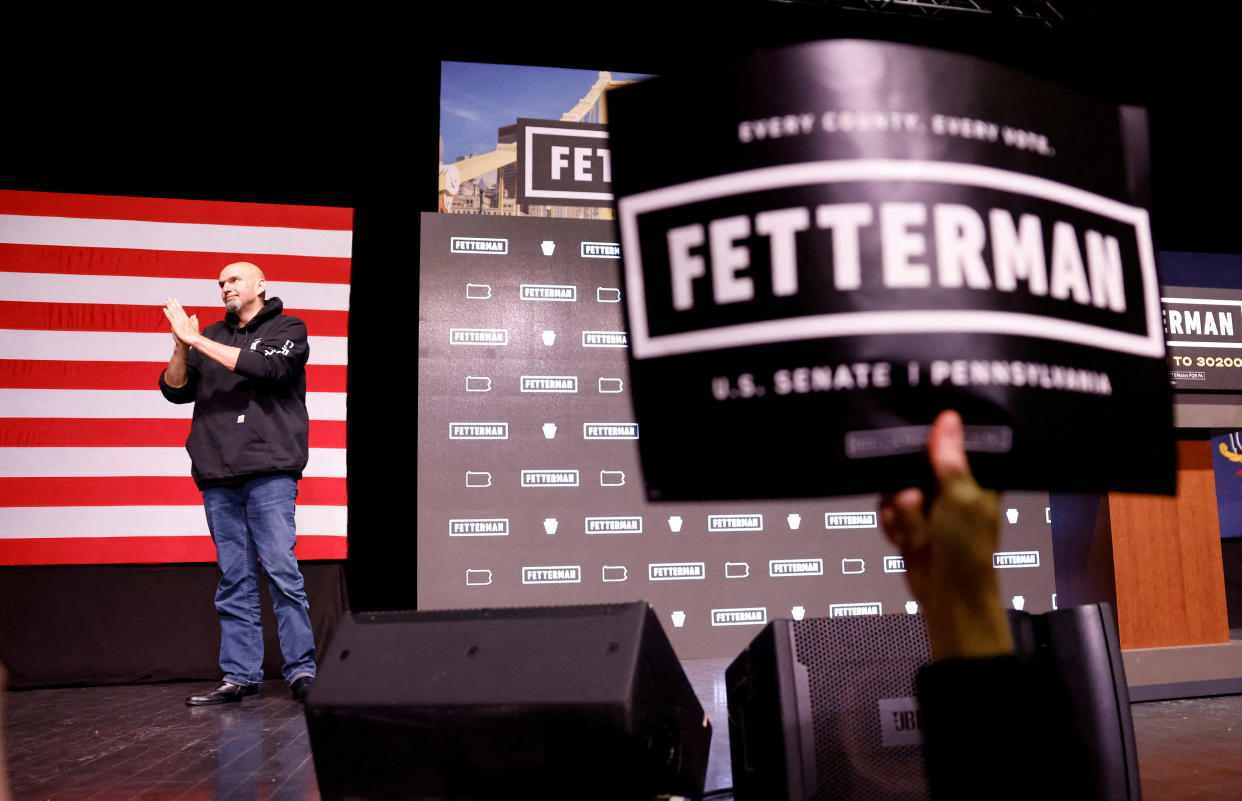

He appeared at a rally in Pittsburgh the night after the debate, saying, “I may not get every word the right way. But I will always do the right thing in Washington, D.C. I have a lot of good days. And every now and then I’ll have a bad day. But every day I will always fight just for you.” The Fetterman campaign announced it had raised $2 million in the aftermath of the debate, while Oz’s favorability ratings and poll numbers asking if he “understands the concerns of voters like you” remained underwater.

The coverage of the debate had followed a discussion earlier in the month about Fetterman using closed captioning in an interview with NBC News to help him with the questions. Following the interview, Ed O’Keefe, CBS News’ senior White House and political correspondent, asked on Twitter, “Will Pennsylvanians be comfortable with someone representing them who had to conduct a TV interview this way?” A common reply from respondents was to ask if this meant deaf Americans should be disqualified from higher office, while reporters who had just completed lengthy interviews of their own with Fetterman criticized what many called an ableist discourse.

The common media lens on Fetterman can perhaps best be summed up in a viral tweet from Yoni Appelbaum, an editor at the Atlantic. Promoting a story from the magazine about whether voters care about Fetterman’s stroke, Appelbaum said, “Completely fascinated by the reaction of Fetterman supporters to his stroke — instead of simply dismissing his struggles, they identify with them.”

Despite the implication from many in the national media that the debate would turn voters on Fetterman, many Pennsylvanians told Yahoo News that while they acknowledged the candidate’s stumbles and occasionally felt pity or discomfort, it didn’t make them change their mind on voting. Many said they were familiar with the struggles of stroke recovery, and they appreciated Fetterman's courage in stepping into a format with a talk show veteran that would have been a tough venue for him even prior to his illness. Those comments were in line with what other reporters heard from supporters.

Polling backed up the comments. A Monmouth University survey released on Nov. 2 found that just 3% of respondents said they were “reconsidering their candidate choice because of what they saw in last week’s debate.” By comparison, 72% of those surveyed said they have personally known someone who suffered from a stroke and had problems similar to Fetterman’s. In the end, the debate did not play a major role: Polling that preceded it showed Fetterman leading by between 2 and 6 points. When all the votes are counted, he will win by at least 4 points.

Fetterman is one of 61 million Americans with a disability, and his time in the spotlight comes as millions suffer from the long-term effects of COVID-19. Studies have shown that the disease can cause an increased risk of stroke for people of all ages, heart attacks and long-term heart problems. A study conducted by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs earlier this year found that those who recover from a severe case of COVID face significantly higher risks of developing new heart problems and other serious cardiovascular disorders, while those who had mild cases still saw an uptick in the chances of developing heart problems versus those who didn’t contract the disease.

Fetterman will not even be the only recent stroke victim in his caucus. When he’s sworn in to the new role, he’ll be one of three Democratic senators who suffered a stroke in 2022, along with Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico and Chris Van Hollen of Maryland.

But he will be unique in that his recovery was so public and so scrutinized. Whether the media overall is more open to disabilities in its coverage remains to be seen, but according to Williamson, Fetterman will have the backing of one large constituency as he moves forward in his new role.

“Whether he likes it or not, he is now a champion in the disability world,” she said. “Because this community was so cheering him on, and I’ve done a couple of other interviews about functioning in the Senate or generally in Congress with any kind of accommodations, and he is certainly entitled to it and I think is up to the challenge.”