Post-holiday COVID-19 data spells a grim forecast for the rest of the year

The experts agree: Last Thursday’s Thanksgiving holiday — traditionally celebrated by far-flung friends and family traveling long distances to crowd inside around communal tables while talking and eating — is about to make America’s scariest coronavirus wave to date even scarier.

“We may see a surge upon a surge,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, told ABC’s “This Week” on Sunday. “We don’t want to frighten people, but that’s just the reality. We said that these things would happen as we got into the cold weather and as we began traveling, and they’ve happened.”

“It looked like things were starting to improve in our northern Plains states, and now with Thanksgiving we’re worried that all of that will be reversed,” Dr. Deborah Birx, coordinator of the White House coronavirus task force, said on CBS’s “Face the Nation.” “We know people may have made mistakes over the Thanksgiving time period.”

“It’s going to get worse over the next several weeks,” U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams added on Fox News.

The question now is how much worse. It’s impossible to say for sure. But by rounding up data from a few different sources — previous holiday spikes, current travel patterns, cellphone proximity trackers and various pandemic forecasting models — it’s possible to get a rough start on predicting what to expect in the weeks ahead.

The early numbers are worrisome.

The first thing to consider is how bad America’s baseline already was. On Nov. 27, right before the holiday slowed down testing and reporting, new daily cases hit 205,460 — the first time the U.S. had ever logged more than 200,000 infections in a single day. On Nov. 24 and 25, new daily deaths passed 2,000 for the first time since May. Right now, a record 93,000 Americans are hospitalized, a number that has tripled over the last two months. Even during the spring’s initial peak, hospitalizations never topped 60,000. The difference today, according to the New York Times, is that caseloads qualify as “high” in every single state except Maine, Vermont and Hawaii — not just a few hard-hit cities or regions.

What that means is that there are a lot more infected (and infectious) people out and about than at previous inflection points in the pandemic.

“If you look at the second wave going into the Memorial Day weekend, we had less than 25,000 cases a day,” Birx said on Sunday. “We had only 30,000 inpatients in the hospital and we had way less mortality, way under a thousand. We’re entering this post-Thanksgiving surge with three, four and 10 times as much disease across the country. And so that’s what worries us the most. We saw what happened post-Memorial Day.”

What happened post-Memorial Day? Cases across the Sun Belt multiplied by a factor of five to 15 over the next six weeks, rising, on average, from about 2,000 to 10,000 in California; from about 350 to 3,500 in Arizona; from about 1,000 to 10,000 in Texas; and from 750 to about 12,000 in Florida. And this was after a warm-weather holiday that Americans tend to celebrate outdoors and close to home.

Thanksgiving will be a bigger problem. To be sure, millions of people decided not to gather with friends and family at all this year; millions more refused to travel, trimmed their guest lists and/or assembled outdoors, masked and distanced. But when assessing danger, you can’t take credit for the comparison with normal Thanksgivings. You have to compare Thanksgiving 2020 with every other day since the start of the pandemic.

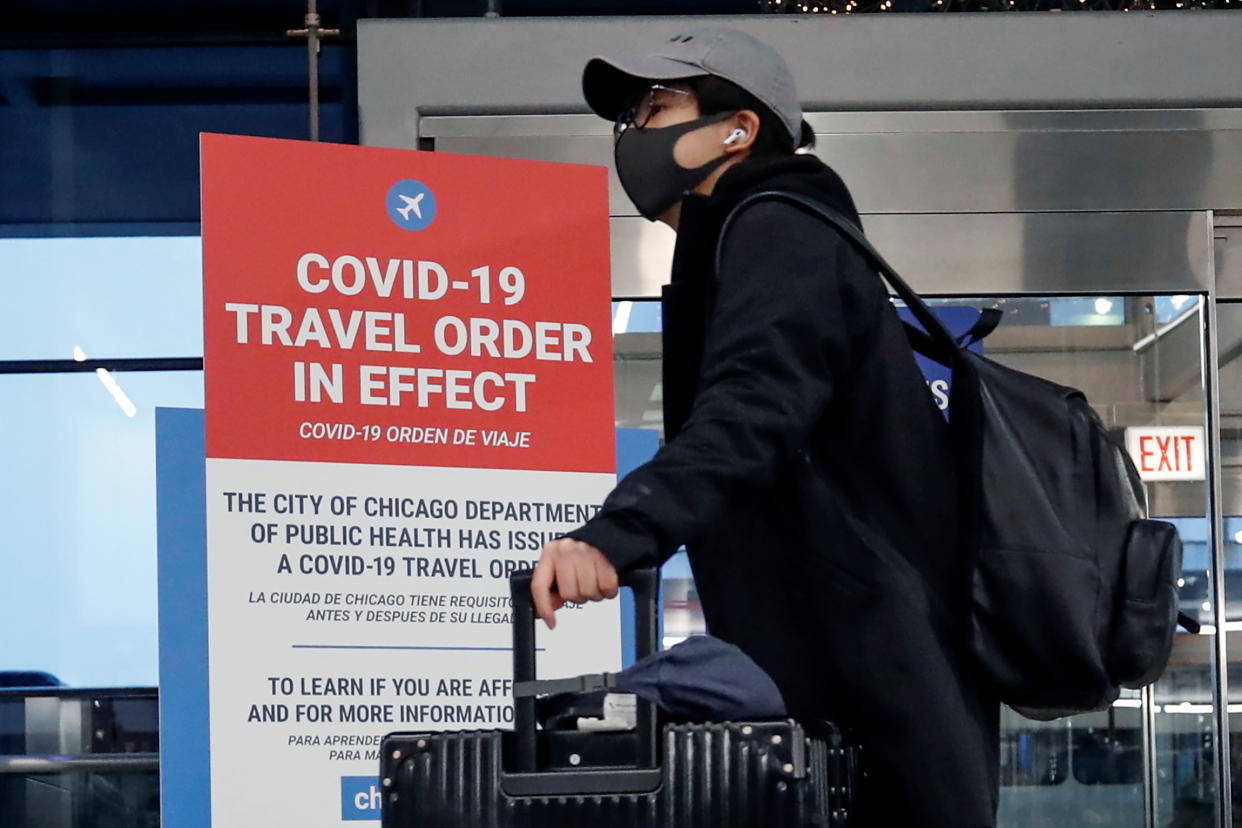

In that regard, Thursday, Nov. 26, was almost certainly the country’s least cautious day yet. On the Friday, Sunday and Wednesday before Thanksgiving, more than 1 million U.S. travelers passed through Transportation Security Administration checkpoints; on the Sunday after Thanksgiving, the TSA recorded 1.2 million travelers, a new high during the pandemic. Since the virus first began circulating widely more than eight months ago, the agency has hit the million-traveler mark only one other time, on Oct. 18. (Only about 341,000 people passed through TSA checkpoints on Memorial Day.) Likewise, a United Airlines spokeswoman told the New York Times that Thanksgiving week was “the busiest since March,” and the American Automobile Association projected that travel by car would be down only modestly from the year before.

As predicted, many Thanksgiving travelers probably didn’t stay 6 feet apart (or outside) during the long weekend. According to Cuebiq, a data intelligence firm that tracks 15 million cellular devices nationwide, overall mobility returned to roughly normal levels in June and has remained there ever since. But while so-called contacts — which Cuebiq defines as “two or more devices coming within 50 feet of each other within a five-minute time period” — initially followed the same curve, they started to diverge in early July.

At first, contacts fell as cases climbed across the Sun Belt during the summer, even as mobility held steady; then, strikingly, contacts rose by about 30 percent from late September to late October, suggesting that many Americans were finally giving up on social distancing. By early November, as cases began surging again, that trend was starting to reverse itself. But between Nov. 21 and Nov. 25, contacts suddenly ticked up another 6 percentage points, hitting a higher level than at any time during the seven months between mid-March and mid-October.

That was Thanksgiving.

So how much damage will the holiday do? No one knows for sure. Several top epidemiological models are already forecasting the COVID-19 death curve three weeks out, and the picture isn’t pretty. As of Monday afternoon, 267,515 Americans had already died from the virus. According to FiveThirtyEight, which aggregates the leading models, the lowest forecast (UCLA) predicts an additional 26,000 COVID-19 deaths over the next three weeks; the highest (U.S. Army) predicts an additional 100,000. The rest — by Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, MIT and others — fall somewhere in between, mostly falling in the range of 300,000 to 325,000 COVID-19 deaths in total by the beginning of Christmas vacation.

But here’s the thing: Someone who was infected on or around Thanksgiving won’t show up in the case counts until later this week or early next week — and, if they’re unlucky enough to succumb to the disease, they won’t register in the mortality statistics for another three weeks after that. Which means we won’t know the true extent of Thanksgiving’s toll until Christmas.

A simple equation recently devised by Trevor Bedford, a genomic epidemiologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, may help prepare Americans for the carnage to come. As Alexis Madrigal and Whet Moser of the Atlantic have explained, Bedford “looked at state-level data to find the best match between case numbers in the past and death numbers some days later. What he found was that plotting the seven-day average of deaths today and the seven-day average of cases 22 days ago maximized the correlation between cases and deaths.”

Once Bedford calculated this lag period, he wanted to know how many of the cases reported 22 days ago would translate into deaths. So he divided deaths on a given day by cases three weeks earlier and calculated this “lagged case-fatality rate” going back in time. What he found is that far fewer people are dying, per reported cases, than in the first phase of the pandemic — no surprise given today’s superior treatments (which save lives) and increased testing (which means fewer cases go undetected). But Bedford also found that these improvements stopped in August. Since then, his lagged case-fatality rate has consistently averaged 1.8 percent — implying that if 100,000 people test positive today, 1,800 of them will be dead 22 days from now.

Apply Bedford’s model to the post-Thanksgiving period, and the implications are disturbing. America’s seven-day average of new daily cases was about 177,000 on Nov. 25. If Bedford’s calculations hold up, that means something like 3,100 Americans could die on Dec. 17, far surpassing the previous high of 2,752 set on April 15.

Looking further ahead, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a forecasting program that synthesizes dozens of forecasts into an “ensemble model” and has proved to perform better than any individual model. This CDC model currently projects that America will be averaging about 185,000 new daily cases one week from today and about 205,000 cases two weeks from today, while allowing that daily cases could average as much as 240,000 by then. Per Bedford, that kind of pre-Christmas caseload would translate into somewhere between 3,700 and 4,300 Americans dying of COVID-19 in one 24-hour period about five weeks from now, on or around Jan. 5. And that’s not even taking Christmas celebrations into account — or the idea that the standard of care is likely to fall in places experiencing major surges.

It’s possible the U.S. pandemic won’t get quite that grim. Perhaps recent mask mandates in hard-hit red states are working. Perhaps falling case counts across the Plains and upper Midwest are a sign that residents there are finally taking the threat seriously; North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Wyoming, Wisconsin, Illinois and Missouri are currently experiencing sharp declines. Perhaps other states like California, where indoor dining is now off-limits and new stay-at-home orders have been put in place, will also turn the corner soon. And perhaps Thanksgiving travelers will follow Birx’s advice to “assume that you’re infected” and adhere to proper testing and quarantining protocols as a result.

But while the patterns of the past can’t always predict the future, the data we have today is not encouraging. Neither are the experts.

“When you have the kind of inflection that we have,” Fauci said Sunday, flattening his hand into a sharp upward angle, “it doesn’t all of a sudden turn around.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: