After a fall, Tucker Marr had a noticeable dent in his head. A 3-D printed skull was the answer

During a wedding reception in 2022, Tucker Marr, then 26, went to his hotel room to change. On his way back to the celebration, he fell down a flight of stairs.

“I didn’t have any visible signs of injury, but I was extremely unconscious,” Marr, 28, of New York City, tells TODAY.com.

Friends called 911 and doctors in the emergency room discovered Marr fractured his skull and experienced a subdural hematoma, which is bleeding in the brain. Doctors removed part of his skull to relieve some pressure to help him recover which left Marr with a cavity on the side of his head. (Doctors do not replace skulls after they’re removed in such situations). As he slowly gained strength and started improving, he felt insecure about the new dent in his head.

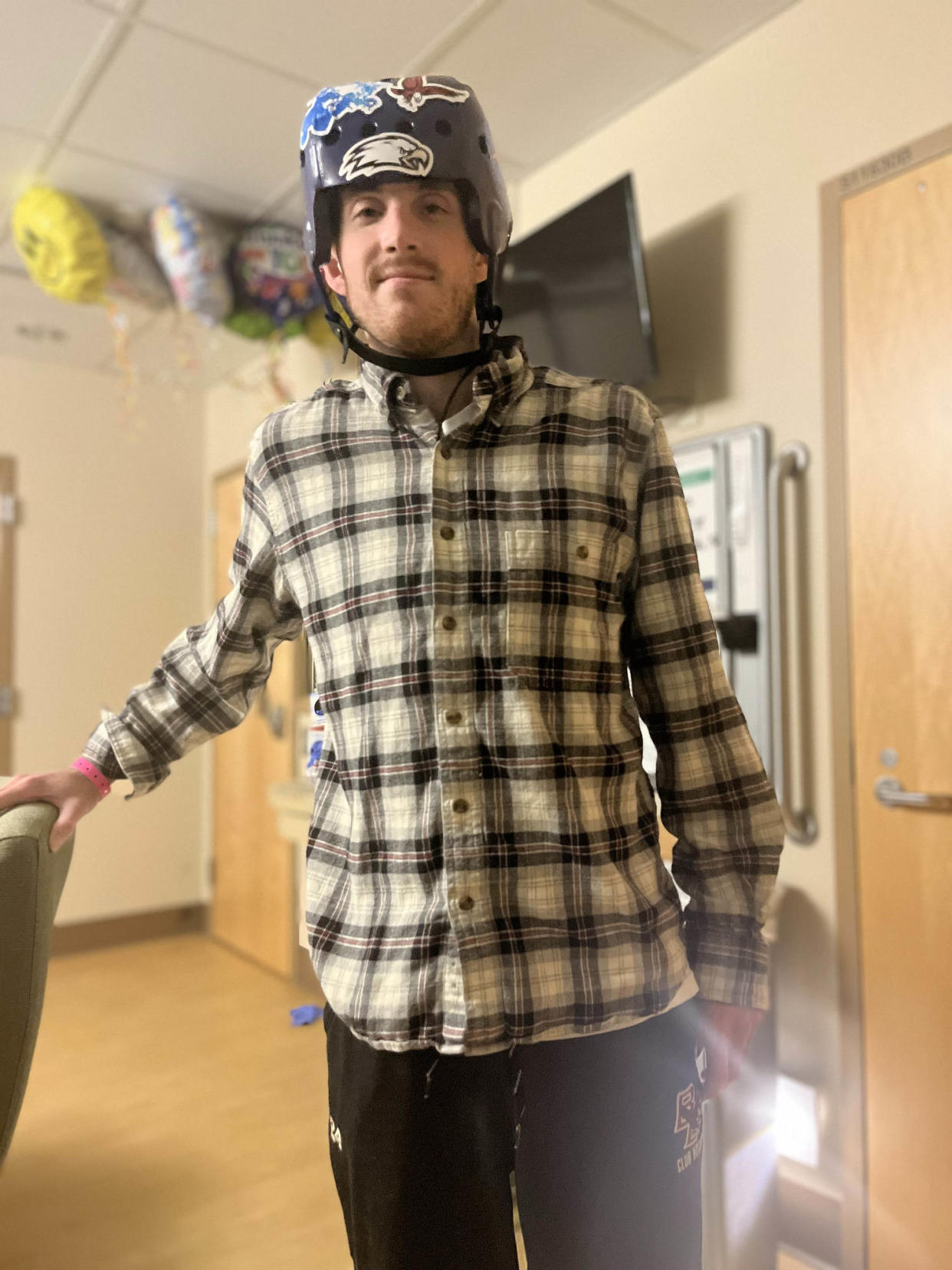

“When you’re wearing a helmet around when you have half a skull and it’s pretty easy for it to become pretty hermit-ish and self-conscious,” he says. So, Marr sought a way he could change his situation and correct the dent. Thankfully, he found one with the help the neuroplastic surgery program at Northwell Lenox Hill Hospital. And now hopes his story encourages others facing health challenges.

An accidental fall leads to serious injury

Prior to the wedding in Minnesota on October 15, 2022, Marr was training to run the New York City Marathon and often played hockey. He remembers having fun at the party, but little else.

“I was definitely enjoying myself, having a good time from what everyone else says,” he says. “I went back to my room after dinner to change and as I was coming down those stairs is when I fell.”

A friend in medical school heard the crash and rushed to help Marr. While he didn’t notice injuries or bleeding, the friend was understandably concerned and called Marr’s girlfriend, Mary, and 911. When paramedics arrived, they were able to rouse Marr slightly with sternum presses, which sparks pain that causes consciousness. But that moment was short-lived.

“It only went downhill from there,” Marr says. “I started really losing consciousness.”

He arrived to the hospital in a coma and underwent a CT scan. Doctors saw there was blood pooled between the dura, the cover of the brain, and the brain, forming what's called a subdural hematoma, according to the National Institutes of Health. Doctors performed surgery where they removed part of his skull and managed the bleeding and relief. Then they placed him in a medically induced coma, which could last up to 10 days. But a few days later, he woke.

“Fitness wise I was in very great shape and is part of the reason that I came out of the coma much earlier than when they expected,” he says.

Though things did not go smoothly when he woke. His blood oxygen levels remained so low that he struggled cognitively.

“I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t move,” Marr explains. “I could say three words … which are very relatable to my personality, which are love you and f***.”

Doctors put him on oxygen to increase his blood oxygenation and after about 36 hours he “got all of my verbal skills back.”

“Obviously not at the fluency I have now but at least I could communicate with people,” Marr says. “I still was so swollen that I couldn’t tell that they had taken out that side of my skull.”

When Marr regained some strength, he tried walking again, but his back muscles seized up, which was “the most painful piece.”

“I was running 50 miles a week. I was playing hockey all the time and then my body was still for about a week and naturally my sciatic nerves (had) a problem,” he says.

Doctors ran more tests, worried that he had a slipped or broken disk. The tests did not reveal an additional injury and he realized that “some painful PT” would be the way back to mobility. About a week after waking, he walked a bit and started recovering. He attended a lot of speech and physical therapy and by Halloween, two weeks after the fall, he was discharged from the hospital. Still, he needed more time to heal and went to his parents’ home in Salt Lake City.

“I had to wear a helmet all of the time,” he says. “As soon as I took off my helmet or showed them the dent people were like, ‘I can’t believe you can even walk.’”

At times, Marr felt self-conscious and worried. Overnight his head would enlarge because of blood flow, he explains, and as the day progressed it would become smaller. People asked to touch his head. Marr’s mom reached out to a neurosurgeon she knew at Lenox Hill Hospital to learn if there was something that could be done so he didn’t have to wear a helmet all the time. That’s when he met Dr. Netanel Ben-Shalom.

“He wanted to … get me back to the lifestyle and the life I had before,” Marr says. “I’m a very active person. I didn’t want to give up skating. I didn’t want to give up hockey. And he understood that.”

Rebuilding a skull

Sometimes when people experience a brain injury doctors need to remove part of the skull to aid healing.

“A surgeon saved (Marr’s) life by removing the skull,” Ben-Shalom, a neurosurgeon at Northwell Lenox Hill Hospital tells TODAY.com. “Without the skull, they allow the brain to swell and sort of expand and with time and recovery the brain goes back to being flat. So we have room to put something back.”

Though research shows that replacing the missing skull with the patient’s own skull isn’t the best practice, he says.

Studies “show that putting bone back is actually worse for the patient for two reasons. One is higher risk of infection,” Ben-Shalom says. The second reason “is a risk of absorption.”

Storing a piece of bone in a fridge deprives it of its blood supply, Ben-Shalom notes, effectively killing it. Returning the now “dead” bone to the skull can lead to infection or cause the body to “eat” the bone. With 3D printing, doctors can replace the missing bone with a customized implant that looks just like the patient’s natural skull without the risks.

About “40% of Marr’s skull on the left side of the head was missing,” Ben-Shalom says. While the helmet protected Marr’s head, he couldn’t live like that forever.

“We know that the brain doesn’t function the same if (it’s) unprotected,” Ben-Shalom says. “The surgery to restore (and) reconstruct the skull is one of the highest complicated surgeries in neurosurgery.”

While replacing the missing bone helps the brain, it also boosts a person’s confidence and allows them to engage in daily tasks without fear.

“You want him to look like himself again,” Ben-Shalom says. “If you can imagine people without half of their skull don’t look like themselves.”

Ben-Shalom and his team 3-D printed “a (customized) implant made of clear acrylic,” which he placed in Marr’s skull in March 2023. By the 2023 New York Marathon in early November, Marr was able to run.

“I tell patients when they’re done with me my goal is they forget about me and forget about their journey and go back to their normal lives,” he says. “We achieved that with Tucker.”

‘Re-stabilized my balance’

The surgery helped Marr have a natural shape to his head and even improved his jaw function, which had become impaired after his injury. The recovery was “quick.”

“I had stitches in my head for about a month and a half but after a week I was playing Padel tennis—against all doctor’s orders,” Marr says. “Surgery really re-stabilized my balance and my athletic ability and my hand-eye coordination pretty quickly. And that was one of the most amazing parts of having that surgery.”

When Marr returned to running and hockey he felt wary. The first time he was in the corner of the ice rink, he worried about being injured.

“That faded pretty quickly,” he says. “I have no fear of injuries anymore and that is really due to the medical professionals I worked with. They instilled so much confidence back into me.”

Marr ran the New York City Marathon in 2023 finishing in three hours and seven minutes. He believes the “love and support” he received from friends and family and a positive outlook helped him recover.

“I’m forever grateful,” Marr says. “My only motivation now is to give (hope) to other people and inspire others to pass that along.”

“Any challenge is really surmountable if you set your mind to it,” he says. “Being an optimist is something that’s very important and will drive the outcome of your wishes and hopes.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com