DOE must develop Hanford’s clean energy park in partnership with Tri-Cities | Opinion

When Col. Franklin Mathias scouted the Hanford site in December 1942, he believed he had found a perfect location to build a plutonium production facility as part of the Manhattan Project. Within a few months, workers were erecting buildings and nuclear reactors.

The Tri-Cities had no say in those decisions. It was the height of World War II, and the race for an atomic bomb was underway. Secrecy and speed were essential. After the war, Hanford remained a cornerstone of the local economy and culture. Uncounted thousands of Tri-Cities residents have worked there.

Now eyes are on the future and what to do with about 14,000 acres adjacent to Richland. That’s a conversation in which Tri-Cities residents, governments and business leaders should have a strong say. It’s our future that’s on the line.

The U.S. Department of Energy, which oversees Hanford, has identified the land for carbon-free energy production — likely solar. It has dubbed the plan, “Cleanup to Clean Energy.” It is already soliciting green energy business interest.

It’s a fine starting point. The United States desperately needs more clean energy sources. The country is slowly moving toward electrification of ground transportation, heating and other things that used to be overwhelmingly fueled by fossil fuels. The Biden administration also might be factoring in the need to replace electricity that would be lost if it continues its reckless rush to breach lower Snake River dams.

Yet as appealing as clean energy is, the Tri-City Development Council makes a strong case that it’s not the best use of this premium land. Solar power can go anywhere that there’s a lot of sunshine, and that’s most places in this part of the state.

This is the only land that abuts northwest Richland, which the city and TRIDEC are trying to turn into the Northwest’s premiere clean energy industrial area. In just the past few months, Richland has agreed to waive taxes for a nuclear fuels facility and a carbon-free fertilizer manufacturing plant.

Richland and TRIDEC are targeting long-term economic development that will provide good jobs for many years. Solar farms, on the other hand, employ few people once they are up and running.

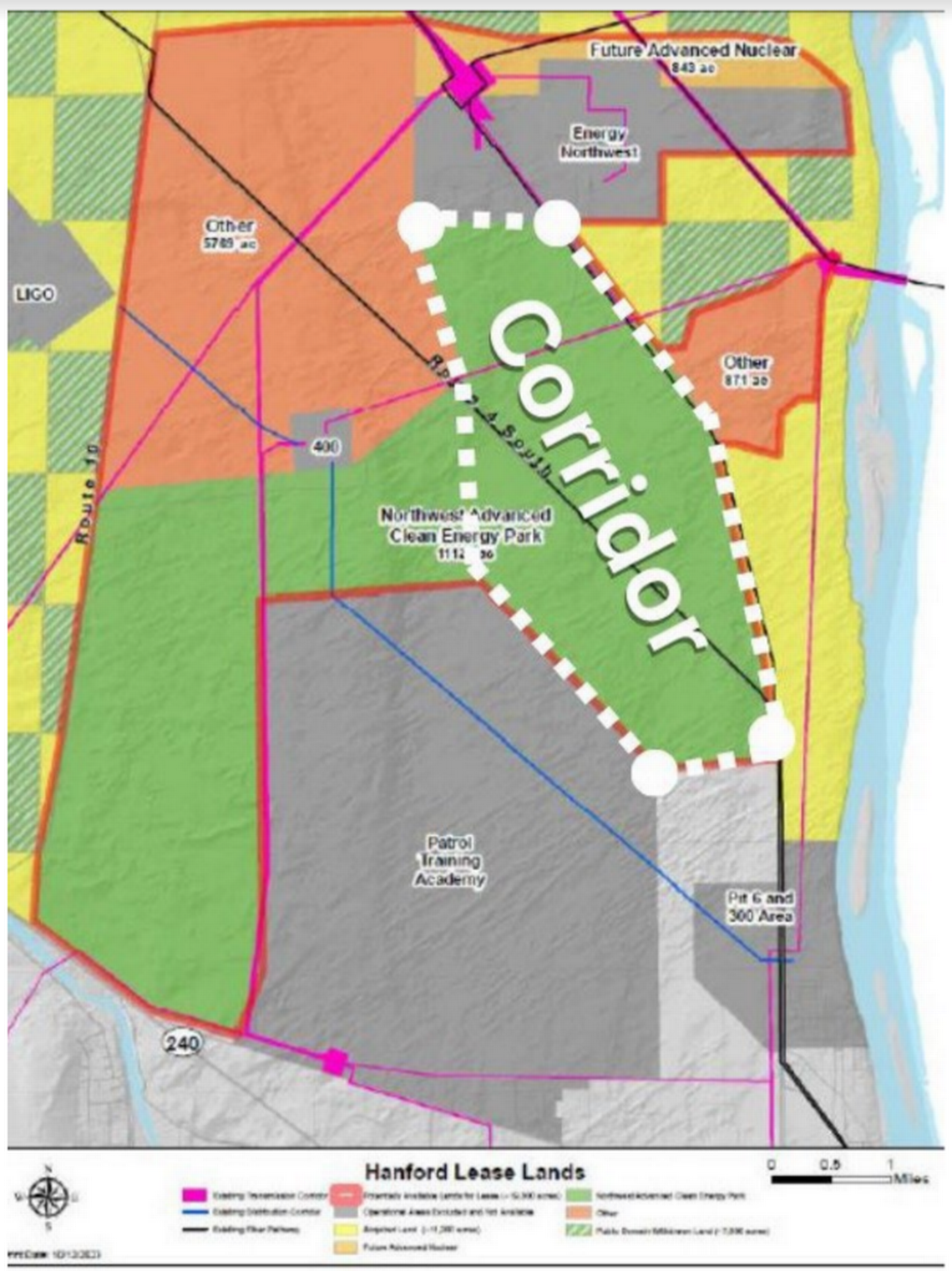

There isn’t one correct approach to making the Tri-Cities a model for a clean, reliable-energy economy. But energy generation and clean-energy industrial uses need not be mutually exclusive. The acres under consideration could provide a lot of room for solar power while still reserving a core area along the Route 4 South corridor toward the Energy Northwest project for industrial development.

The only way we get there is if the Energy Department slows down and better engages with local leaders who have a much better sense of what sort of development will serve the community best. The Energy Department hosted a community meeting last September in Richland to discuss the plans.

About 100 community residents and industry leaders showed up. But a Q&A session isn’t enough. There should be ongoing coordination that accounts for the needs of locals who will have to live next to whatever happens at Hanford.

It won’t be easy, of course. There would be competitive demands for the properties, and the direction that the Energy Department wants to go has a head start. There also would need to be partnerships between power generators, distributors and industrial users in the area to share some of the power produced on site. There’s little sense in pumping it out to the grid when it can be so productive nearby.

These are not insurmountable challenges if the competing interests come together now.

TRIDEC officials say that the Energy Department wants Cleanup to Clean Energy deals ready to be announced in September, though they refused to speculate on why that might be the deadline. In any event, there shouldn’t be a rush.

The land isn’t going anywhere, and decisions that are made now will affect the region for generations, long after cleanup is complete. Make them with intentionality, forethought and broad community partnerships.

The Tri-Cities didn’t have a say 80 years ago; they deserve one today.