Detroit housing court reopens with big changes and fears of more evictions

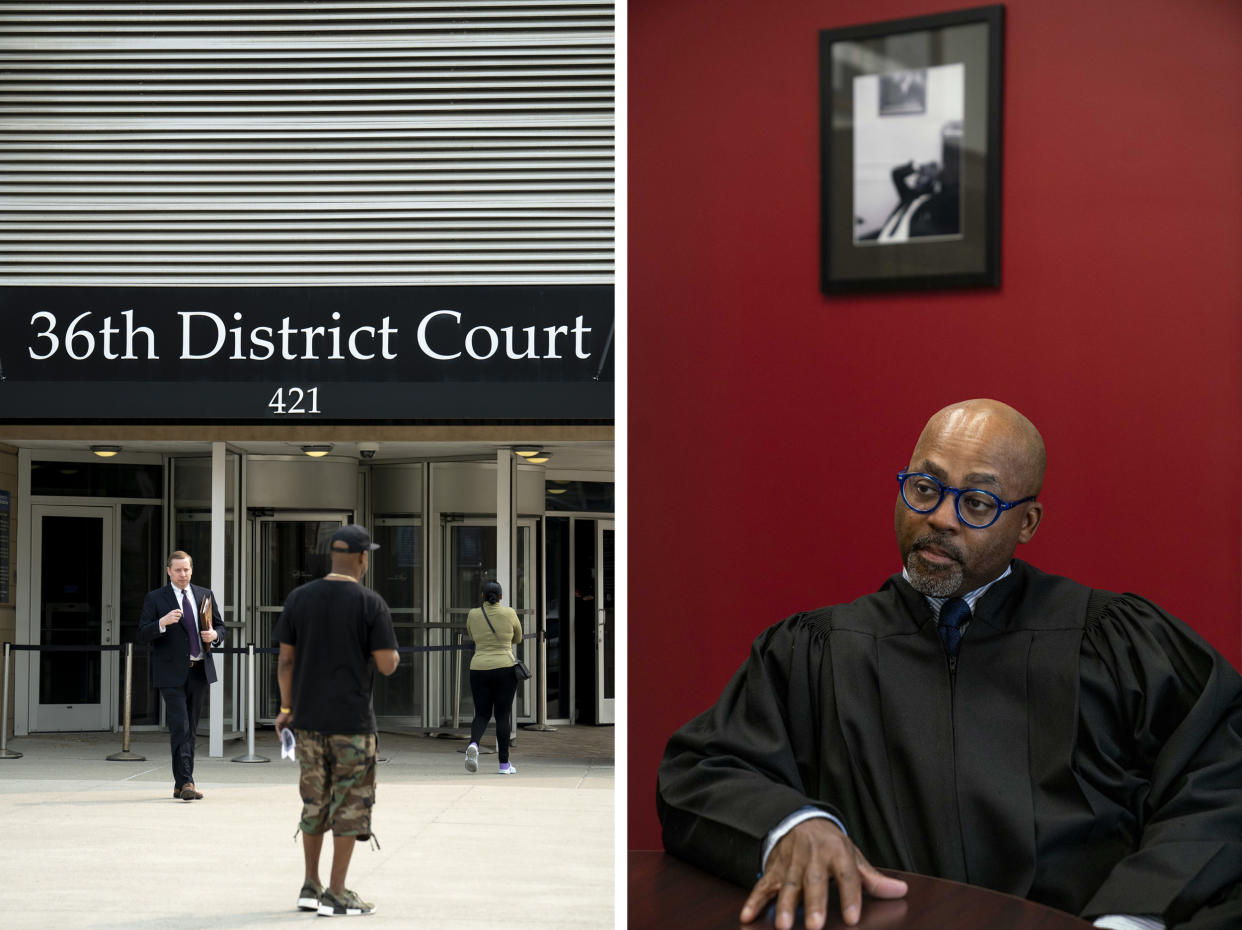

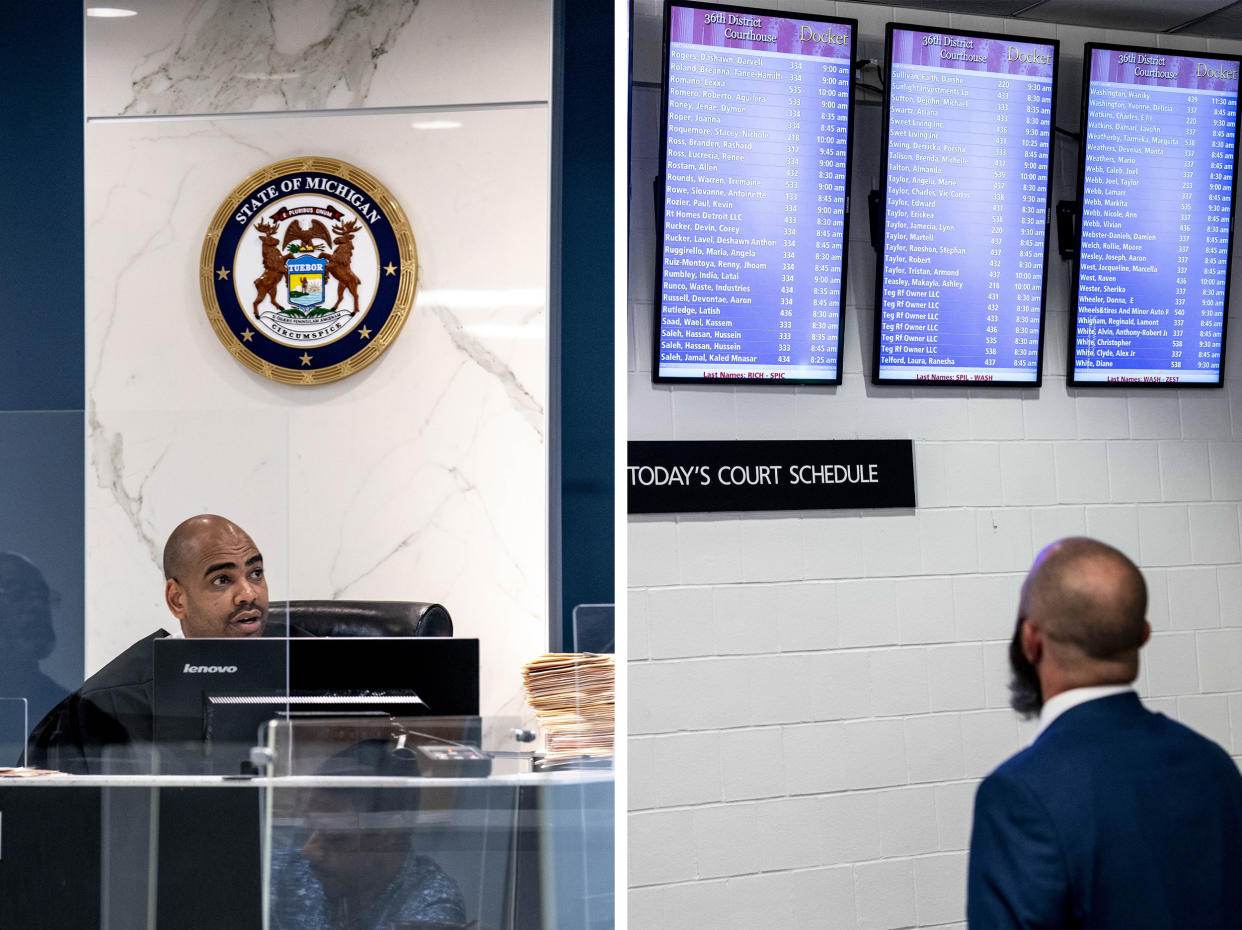

DETROIT — Those passing the municipal courthouse in downtown Detroit on Monday saw something they hadn’t seen in years: a rush of people coming and going.

The city’s bustling housing court had resumed in-person hearings for the first time since Covid forced them online.

The move — expected to last at least three months so the court can catch up on a backlog — has housing advocates fearing that evictions will spike for tenants who can’t take time off from work or find child care. Advocates point to court data showing that default judgments against tenants who failed to show up for their hearings dropped to 25% when court was online, compared to 46% before the pandemic.

Evictions are still well below pre-pandemic levels but are climbing quickly, court data shows. In the first four months of the year, judges signed more than 1,800 evictions. That’s roughly half the number signed in the same time in 2019, but still much higher than last year.

The court couldn’t immediately say how many tenants failed to show up on Monday, but Chief Judge William C. McConico noted that Detroit’s housing court — like many such courts around the country — is now “completely different” than it was pre-pandemic.

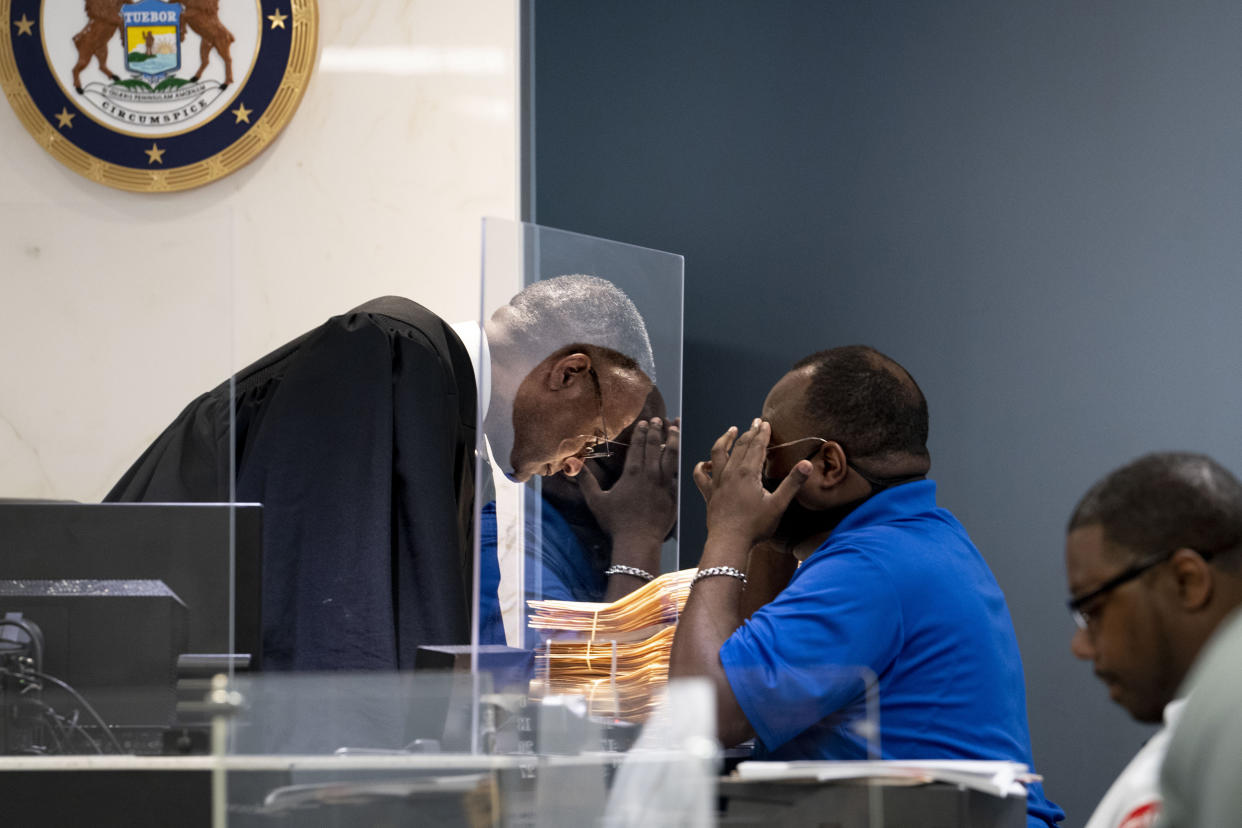

Before Covid, when the city saw 10,000 evictions a year, tenants could be kicked out after missing a single court date. Now a state Supreme Court order requires two housing court appearances before an eviction. Some low-income tenants also now have access to free lawyers through a program that was funded during the pandemic by federal Covid relief dollars and is now supported by the city and a local foundation.

Kenyatta Jefferson, 31, experienced both the good changes and the bad on Monday.

He and his girlfriend, Shermeka Powell, 32, both had to miss work — he works in an auto plant, and she works at Ford Field, the city’s football stadium — costing them each a day’s pay, they said. They also had to bring their 3-month-old daughter, whose needs — and the fact that people kept stopping them to admire the baby — made it harder for them to arrive on time.

By the time they got to court for the second and possibly final hearing of their eviction, they were 10 to 15 minutes late, they said, and were told that a default judgment already had been issued in favor of their landlord, Jefferson’s mother.

That wouldn’t have happened if the court had still been online, Jefferson said. “I would have been on time and I wouldn’t have had to call out of work.”

Jefferson’s mother, who asked not to be identified, said in an interview that she also had to miss work, leaving her 24-hour day care business. It was worth it, she said, because her son doesn’t pay the rent, ran up an expensive water bill and is disrespectful. (She also said she believes her son was at least 30 minutes late for court.)

Thanks to the free legal aid program for tenants, Jefferson had access to help. He was directed to organizations that now have staff members working out of closets and offices around the courthouse. One of them began preparing paperwork to get his case reopened. He and Powell are hoping they can stay in the house they live in on Detroit’s east side. “It’s so unreal,” Powell said. “Having a home to live in when you have kids is really important.”

Across the country, far more courts are holding hearings online than before the pandemic, when it was relatively rare. And that’s not the only way that housing courts have changed, said Samira Nazem, who leads an eviction diversion initiative for the National Center for State Courts, which provides technical assistance to state court systems.

“There has been a culture shift in housing court,” Nazem said.

Before the pandemic, court officials were focused on jammed and backlogged eviction dockets and avoided doing anything that would appear to compromise their impartiality, Nazem said. But their role in implementing pandemic-era programs like eviction moratoriums and emergency rental assistance reduced their reservations about assisting tenants in need, she said.

“Covid really kind of crystallized for many courts the important role they can play in connecting people to services and resources and that that’s not an inappropriate role for courts to play,” Nazem said.

Although Detroit now has free legal aid available in the courthouse, attorneys warned that they don’t have the resources to represent every eligible tenant, although they did appear to meet the demand on Monday.

Brittany Jennings, 29, was referred to attorneys after taking a 45-minute bus ride to court with two small children and her mother, who walks with a cane. The family hopes attorneys can help them stay in their home of seven years and get the landlord to fix the broken water heater, which has forced her to boil water to bathe her children, she said.

“I’m happy I got more time,” she said. “But it’s inconvenient.”

The family is facing eviction after their downstairs neighbor bought the house from the city through a community program that helps tenants buy the city-owned homes they’re renting. Their neighbor-turned-landlord, Carmen Gamble, 51, said the Jennings family haven’t been paying rent and have damaged the property.

“I just want y’all out of here,” she said she told them. She confirmed that the water heater is broken and said she’s applying to support programs to get the money to fix it.

Some landlords said they hope that in-person court will be more efficient.

“We’re getting something done,” said Milton Ferguson, who owns an apartment and four houses in Detroit and says evictions have been difficult since the pandemic. “It was always postponements, adjournments and kicking the can down the road.”

Larger landlords might be able to weather delays, but for his small business, the effect has been “devastation,” he said. “It’s a hardship because the pressure is on me to pay the mortgage, the taxes, upkeep, insurance.”

The National Housing Law Project, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that advocates for tenant rights, has called on courts to let tenants choose whether to appear in person or online. That would help people who don’t have a device or an internet connection and would make it easier for courts to process documents such as leases or payment receipts.

McConico, the chief judge in Detroit, said he will be closely watching what happens and will make changes as needed to “ensure that this program is a success and that everyone’s rights are protected.”