The COVID public health emergency expires Thursday. Here’s what that means for you.

On Thursday, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will allow the federal public health emergency for the COVID-19 pandemic to expire, but not everyone sees it as a cause for celebration. HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra had renewed the emergency for 90 days in February, signaling at the time that this would be the last extension.

Coming one month after President Biden signed a Republican-backed bill repealing a separate national COVID emergency declared by President Trump in March 2020, and six days after the World Health Organization declared the global COVID health emergency over, the latest news seems like the capstone on a building consensus that COVID-19 is no longer a crisis.

But over 1,000 Americans continue to die from COVID each week, and countless more are developing debilitating long COVID, so disability advocates are arguing that allowing the protections associated with the public health emergency to lapse is dangerous and irresponsible.

“We've called off the fire department while the house is still burning, because the neighbors want it to be over,” said Laurie Jones, executive director of #MEAction, an organization that advocates for people with myalgic encephalomyelitis, a chronic fatigue condition that a large share of long COVID sufferers develop, in a Wednesday press briefing.

Here’s a guide to what the expiration means and what some say should not be forgotten.

What already had changed

The national emergency that ended last month had given the federal government a broad range of powers over the economy. For example, it gave the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) the ability to create the COVID-19 mortgage forbearance program. That program will expire at the end of May, and the Department of Veterans Affairs has returned to requiring in-home visits to determine eligibility for a program that pays home caregivers.

What will change now

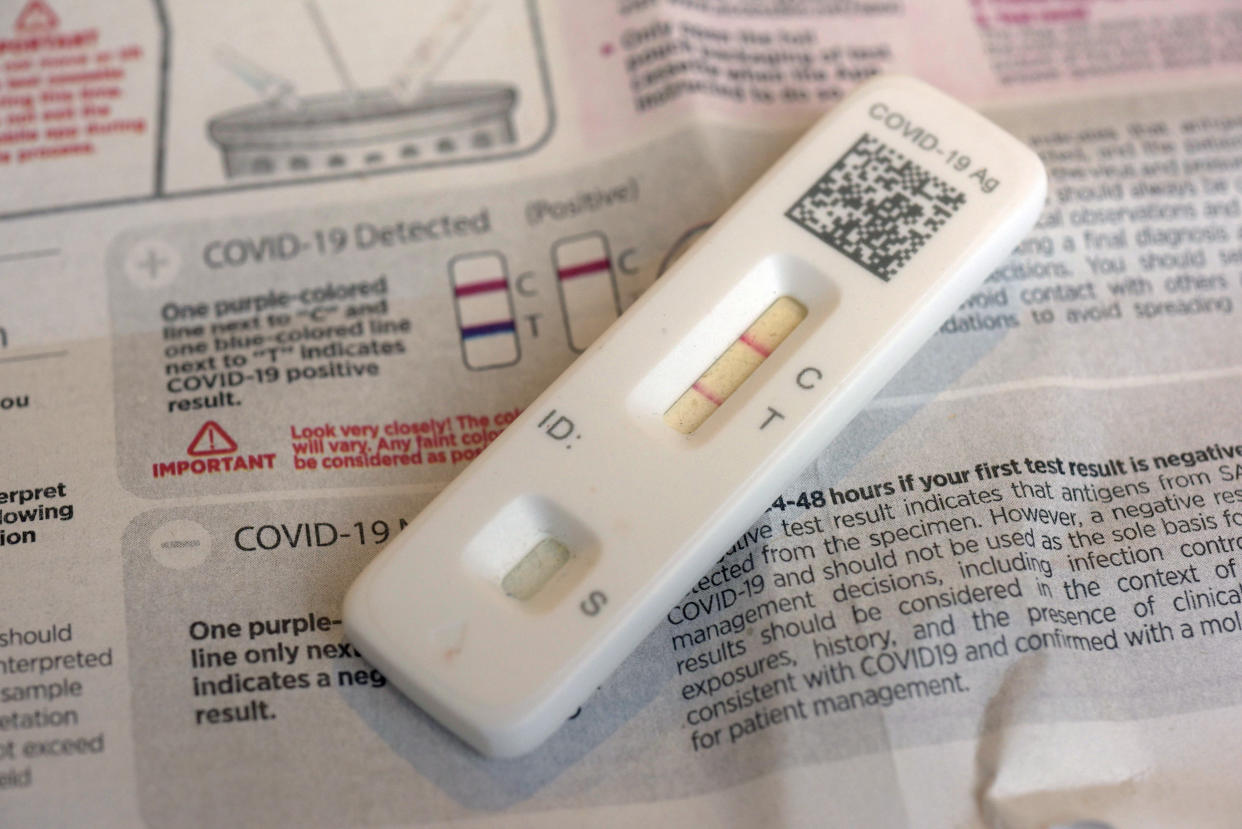

The public health emergency ending on May 11 allowed the federal government to freely provide COVID-19 tests, treatments such as Paxlovid, and vaccines. Americans with Medicare or private insurance plans have been able to get up to eight COVID tests per month from pharmacies with no copay. (Medicaid rules varied by state.) Therapeutic treatments such as monoclonal antibodies have been fully covered by Medicare and Medicaid.

All of that is about to change. Medicare beneficiaries will now have to pay a portion of the cost of at-home COVID tests and for COVID treatments. Essentially, COVID will be covered the same way as other conditions. People with Medicaid coverage will get cost-free vaccines and COVID tests when ordered by a doctor, but they will have to pay out of pocket for at-home tests. Those with private insurance may have to pay for tests, even when ordered by a physician, and for COVID treatments.

“People will have to start paying some money for things they didn’t have to pay for during the emergency,” Jen Kates, senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told CNN when the May 11 deadline was first announced. “That’s the main thing people will start to notice.”

Tests will remain free until the supply purchased by the government runs out.

There will also be less comprehensive tracking of the spread of COVID-19. Infections will no longer be monitored, only hospitalizations, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will no longer offer a color-coded rating of the severity of COVID-19 in each county.

Perhaps most controversially, Title 42, a Trump-era component of the public health emergency that allowed the U.S. to quickly remove migrants, will expire. Officials expect a subsequent surge in migrants at the southern border. In response, congressional Republicans are pushing a bill to bring back some of Trump’s immigration policies, including the construction of a border wall.

What won’t change

Vaccines will remain free to anyone with health insurance, due to federal laws, including the Affordable Care Act and pandemic-relief bills.

For those without insurance, all of these benefits have already become costly, as federal funds for free COVID-related health care to uninsured people ran out at the end of last year.

What is separate from the emergency

In a March 2020 COVID-relief law, states were prohibited from removing anyone from Medicaid during the public health emergency, but Congress already reversed that last year, with states being able to revoke Medicaid coverage as April 1 of this year. Millions of people, including an estimated 6.7 million children, may lose coverage as a result.

Food stamp benefits were also increased as part of a 2020 relief measure, but that expired in March.

Expanded access to telehealth that was created during the public health emergency will be separately kept in place through the end of 2024.

What high-risk populations might still need

Many people with disabilities are at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 or having severe symptoms because of prior conditions such as a weakened immune system. Advocates for disabled people are concerned that without free access to tests and treatments, some people won’t be able to protect themselves. They note that free access could be extended through separate legislation rather than an extension of the emergency.

To protect those who are most vulnerable to infection, disability rights activists argue that mask mandates should still be in place in health care facilities — although that is managed at the state level — and that the CDC should still track COVID rates so that people can make informed decisions about how much to go out in public.

“The pressure to end the public health [emergency] was enormous, but it didn’t have to be an either/or situation,” Jones said on Wednesday. “It could have both/and. We could’ve helped people reenter the world while still masking in hospital settings, tracked COVID rates and warned people of spikes in their area. We could still offer free testing and free treatments.”

Some public health experts agree, warning that new variants of the coronavirus could prove more transmissible or more deadly. “The need for active management of the virus continues. Many thought the pandemic was over in the spring of 2021,” Boston University public health professor Julia Raifman told Yahoo News in April. “Unfortunately, we were not prepared for new variants, and we lost hundreds of thousands of lives in the following months. By actively tracking COVID, continuing the work to help people get vaccinated and boosted, and having policies and supplies in place to address new variants, we can help ensure we do not see such a high preventable toll again.”