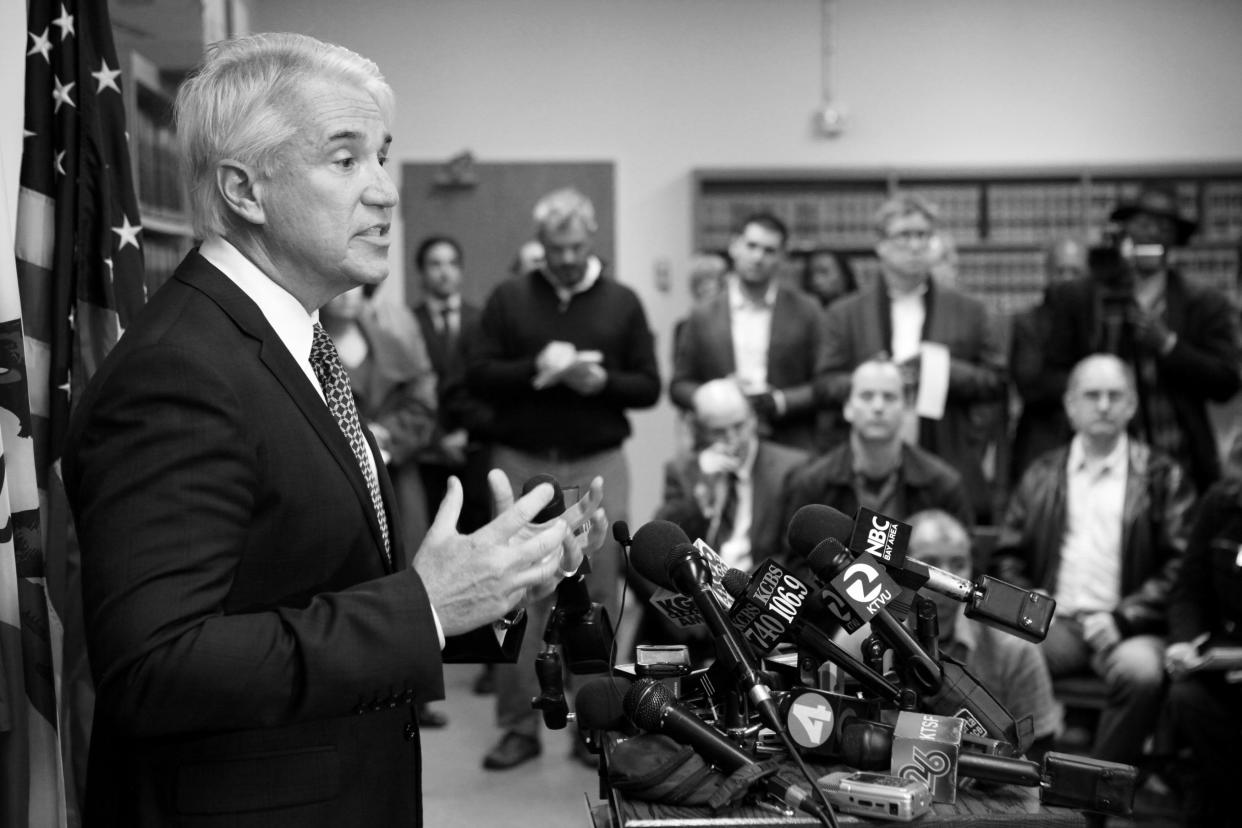

Controversial Los Angeles DA Gascón vows '100%' fight against recall

Embattled Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón is vowing to “100%” fight a recall campaign that he blames on “unscrupulous politicians” who are scaring voters about rising violent crime rates and hard-line “ideological” prosecutors in his own office who have balked at his progressive policies.

“You have unscrupulous politicians who basically will tailor their message to what they think is polling well,” Gascón said in an interview for the Yahoo News “Skullduggery” podcast when asked about a recall campaign that claims to have raised more than $3.5 million in an effort to remove him from office in this fall’s elections. (Last year, a similar recall effort failed to gather enough signatures to qualify for the ballot.)

“This work is too important for the community that I love,” Gascón said of fighting the recall. “The community that embraced me since I was a young kid — a community where my kids were born, my grandkids were born. This is too important.”

As for the resistance he has faced from members of his own staff, Gascón dismissed his internal critics as old-school, law-and-order prosecutors wedded to what he views as the failed policies of the past.

“This group of prosecutors that has opposed me — they were opposing me during the elections. They spent a lot of money running against me. They were talking about a recall the first week that I got elected. I think it's important to contextualize who are prosecutors, public defenders, police — like, these are extremely ideological careers,” Gascón said.

Gascón, who started his career as a Los Angeles beat cop before serving as assistant LAPD police chief and San Francisco DA, has emerged as among the most high profile — and polarizing — of a wave of progressive prosecutors elected in the wake of the social protest movement ignited by the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers in May 2020.

From the moment he took office, Gascón ordered far-reaching changes to the way L.A. prosecutors do business, mandating an end to cash bail, life sentences without parole and the prosecution of anyone younger than 18 as an adult — without exceptions.

And in what the New York Times called “a rare, if not unprecedented, move by an American prosecutor,” Gascón also declared his intent to effectively “end very long sentences — in pending cases as well as new ones — for some of the most serious crimes, including murder.”

“We need to understand that the answers and the solutions that got us in trouble in the '90s and for the last 30 years are not the solutions that are gonna get us to a better place,” Gascón told Yahoo News.

But as homicide and violent crime rates have climbed during the COVID-19 pandemic — in areas with both “progressive” and “conservative” DAs — Gascón’s attempts at reform have repeatedly met resistance from prosecutors, police officers and at least one state judge who shot down a decree directing the DA's office not to seek enhanced sentences under California’s “three strikes” sentencing law.

Meanwhile, an association of deputy district attorneys — which represents the prosecutors in Gascón’s office — last month overwhelmingly voted to back the recall after accusing him of a “serious breach of public trust” due to “purposeful inaction in the face of increasing and distressing violence against innocent members of the public.”

In response, Gascón has started to moderate some of his most progressive policies, quietly conceding in recent weeks that there can be exceptions to his bans on seeking life sentences in murder cases or trying juveniles as adults.

Such compromises may reflect a turning point for the progressive-prosecution movement as it seeks to maintain public support in the face of rising concerns over violent crime — the same dynamic that has prompted President Biden to distance himself from left-wing demands to “defund the police” by proposing an additional $32 billion to fight crime.

“As human beings, we need to continue to evolve,” Gascón told Yahoo News. “I kept listening to the public; I kept listening to people inside and outside. And we’ve gotten to what we have as a result of that journey.”

In his most high-profile shift, Gascón was forced to admit last month that his office was wrong to have tried as a juvenile a transgender woman accused of sexually assaulting a 10-year-old when she was a teen after she was caught on a tape mocking her victim and boasting that she wouldn’t have to spend any meaningful time in jail.

“When I became aware of the audiotape — which came much later, past the resolution of this case — I found it to be disgusting,” Gascón told Yahoo News. “I found her to be just completely devoid of any remorse or any understanding of the harm she caused. Retrospectively, had I had a different opportunity — had I had that information — would I have gone in a different direction in the case? The answer is probably yes.”

What follows is an edited transcript of the “Skullduggery” interview conducted in Gascón’s office by “Skullduggery” co-host Michael Isikoff and Yahoo News National Correspondent Andrew Romano.

Isikoff: I want to start out by asking you about your reaction when you heard the president in his State of the Union speech say, “The answer isn’t to defund the police, it’s” — and I’m quoting the president exactly here — “fund the police, fund the police, fund the police.”

Gascón: I understand why the president did what he did. We live in a world of very simple messaging — "build that wall," "lock her up." It’s effective, right? And as someone that was in policing for 30 years before I became a prosecutor, I deeply appreciate policing.

But I also grew up very poor. I grew up in some very rough areas. And the relationship with policing was mixed. On the one hand, we wanted good policing to feel protected. On the other hand, we often felt singled out and treated in ways that people in other neighborhoods would not be treated.

And that hasn’t changed. Part of the legitimacy of the entire system, not just policing but prosecutions and our entire criminal legal system, [is] that people trust and believe that the system is going to treat them fairly, equitably — that they’re gonna be respected, that there’s gonna be proportionality.

So I think that the problem with the whole concept, defund or fund the police, is that they’re terms that sound sexy depending on where you are politically. But I think it oversimplifies extremely complicated issues.

I’ve never been one that said "defund the police." I do believe that we have to also think about funding education, public health, social services, all those other things.

Isikoff: But you’re the DA — you’re not in charge of the social services department.

No.

Isikoff: So do you accept, especially in a time of rising violent crime — which we have in many inner cities, including in Los Angeles here — that we do need more police on the streets and more funding for the police?

I think that we need better policing. And whether that requires more people in uniform, the same or different kind of policing — I think that those are all questions that are still open.

And while it is true that violent crime has increased throughout the country, interestingly enough ... in California, we see in communities where you have really strict district attorneys, proportionally their violent crime has gone up more than in communities like mine.

We need to understand that the answers and the solutions that got us in trouble in the ’90s and for the last 30 years are not the solutions that are gonna get us to a better place.

A lot of the problems that we’re having today, many researchers and certainly a lot of data would point out that they’re sometimes a direct [result] of ... over-incarceration and underinvesting or divesting in many communities. Then what happened is COVID came in … and all of a sudden, all the infirmities of a system that has been barely surviving economically and socially just came to a screeching halt.

[It’s like] you’re in the 14th round and you just needed Muhammad Ali to come in and land the knockout punch. That was COVID.

Romano: You might be the most progressive of the progressive prosecutors. You certainly put into place, from your very first day in office, policies that some other progressive prosecutors have resisted — not trying any juveniles as adults, for example.

As a result, you’re now facing your second recall effort. Why are you getting so much resistance after getting elected by a wide margin? Did something change? Or did you miscalculate?

There is no question that there has been an uptick in violence in this community and throughout the country. The numbers are there.

But if you take a 10-year look ... we’re still relatively in a very good place. Not to make excuses or to say that we should be comfortable with that. To the contrary, I go to bed at night thinking about this stuff; I get up in the morning thinking about it.

But ... it is very political, right? This is an old playbook. It was played in the ’70s. The L.A. Times recently talked about “make America afraid again.” It’s a playbook that gets repeated.

Then you have unscrupulous politicians who basically will tailor their message to what they think is polling well. And unfortunately you also have a combination of intentional misinformation in the media [and] the impact of social media on how people consume information.

[Recently] this very smart lady in Beverly Hills [told us, after learning about the actual crime numbers in her area], “You know what [Gascón’s] biggest problem is? ... He doesn't have a good PR firm.”

We’re in this world where it’s not necessarily about the facts — it’s just how you present things, how you package them.

Isikoff: But the resistance hasn’t come only from across the political divide. Your own staff, your own prosecutors have sued you over your directive to basically ignore the "three strikes and you’re out" law. And the judge rebuked you for doing that and saying you were asking prosecutors to take a position that was unethical for them.

This will be in appeals; it will go to the Supreme Court. But we didn’t lose. It was a split decision. Prosecutors exercise that discretion every day. Even in this office, we never filed every single three-strike case.

This group of prosecutors that has opposed me, they were opposing me during the elections. They spent a lot of money running against me. They were talking about a recall the first week that I got elected. I think it’s important to contextualize who are prosecutors, public defenders, police — like, these are extremely ideological careers.

Then here comes someone who is talking about transforming and taking the system in a different direction and basically puts into question everything that you believe in — things that, quite frankly, have been the path to success: More trials. More punitive convictions.

All of a sudden you have somebody who says, “You know, some people need to go to prison.” But we need to be more measured in the way that we intervene, and we need to think about not only the case in front of us, but the impact multiple layers down the road.

Romano: But Angelenos are worried about the increase in homicides right now — up 77% from 2019 across L.A. County. They worry about homelessness, they worry about robbery in their neighborhood. How is your approach actually working and not just making things worse?

If we went to places that have traditional prosecutors and their crime was going down, I would be the first one to come back to the office and start saying, “OK, I gotta do something differently.” But when I see crime in some places like Kern County is going up at a higher per capita rate, or Sacramento is going up — they have a completely different approach and they’re having the same problem. I have to stop and say, “OK, there is something beyond what a prosecutor does that is impacting crime.”

And if locking people up for longer periods of time is not causing crime to go down, and if locking people up for lower periods of time is not causing crime to go up, what do we do? How do we look at this in the short term?

So here are the things that I point to. The city of L.A. now, year to date, has a 23% reduction in homicides...

Romano: You’re saying the homicide rate in the first few months of 2022 is 23% lower than the homicide rate in the first few months of 2021.

Right. We’re beginning to see the trends go in the other direction. ... And we actually prosecuted more felonies last year than in, than in prior years, percentage-wise. We created the Community Violence Reduction Division [to reduce gang-related crime]. We put prosecutors, investigators in this office. But we also brought in public health and community [leaders] and the police to areas that are really, really challenging and have been very challenging for decades. We’re beginning to see breakthroughs there.

Look, last weekend, there were 50 shooting victims in this country, and four of them happened in four different cities in Texas. One, I believe, it was Arkansas. One’s in Virginia. One’s in Florida. All of them are strong Republican [places] with very hard-core prosecutors. Can you imagine if one of those shootings happened in L.A. this weekend? CNN would be breathing down my door.

Isikoff: Hannah Tubbs, a 26-year-old transgender woman, pleads guilty in juvenile court to sexually assaulting a child at a Denny's restaurant. She’s caught on tape mocking the sentence, talking about how she’s going to go free, she’s going be out on probation. She’s making disparaging remarks about the victim and others. You initially tweeted, “This is not an acknowledgement we made a mistake in the Tubbs case by directing that she be tried in juvenile court rather than adult court despite the severity of the crime.”

Then, after the tapes came out, you tweeted, “If we knew about her disregard for the harm she caused, we would have handled this case differently.”

What was your reaction when you first heard those tapes, and do you now acknowledge it was a mistake to direct that case to be tried in juvenile court rather than adult court?

So first of all ... this young person was 17 when she committed the crime. She’s now 26. When we initially looked at the case, we were looking at the case as when the case occurred — not where she is now but where she was. I also look at information that is confidential concerning mental health and medical issues and all that stuff. All that together as a package led me to believe that this case would be better served if it remained in the juvenile jurisdiction.

Now, when I became aware of the audiotape — which came much later, past the resolution of this case — I found it to be disgusting. I found her to be just completely devoid of any remorse or any understanding of the harm [she caused]. Retrospectively, had I had a different opportunity — had I had that information — would I have gone in a different direction in the case? The answer is probably yes.

Having said that, whether you’re going one direction or the other — whether you’re a law-and-order prosecutor or [not] — we live in a world where there’s always going to be a bad case.

Romano: But [you came into office with a] more aggressive approach, where you wanted to try to rule out any exceptions at all because you were pushing for as much reform as possible.

Have you now moderated that approach? Were you wrong not to be more cognizant of the fact that there will be these bad cases and build those exceptions into the system?

I believe that, as human beings, we need to continue to evolve. If you were to talk to me ... maybe 25 years ago ... I was pro-death penalty. I believed that ... if you do an adult crime, you pay an adult price.

I’ve learned a great deal. I have educated myself a great deal. I’ve arrived at a different place. When I first came into office, I came into [one] set of circumstances. Since then, we have put a different team in place. We have different capacity. At the same time I kept listening to the public; I kept listening to people inside and outside. And we’ve gotten to what we have as a result of that journey. A year from now, you may see other tweaks in other areas.

Isikoff: From a philosophical perspective, you’ve articulated a certain vision that has been called restorative justice.

But there’s another philosophy about crime and punishment, and it was articulated most recently by William Barr, the former attorney general, in his new book, where he argues that the real purpose of criminal justice is retribution: When someone commits a crime, a punishment proportionate to the offense is justified and required solely to address the transgression and restore society’s moral order. That punishment is due regardless of any social utility the punishment may otherwise have in controlling crime in the future.

Mr. Barr’s assessment — it’s a good 19th century approach to the work, when we had no understanding of the impact of trauma, the impact of brain development in human beings, what works, what doesn't work.

We spend millions and millions of dollars in a process that creates more insecurity, and it takes funding away from other things like education, housing and other services.

Romano: You mentioned your “journey” and how you’re continuing to evolve. Upon taking office, you said that you’re “not the same man” you were when you “first put on the uniform.” What changed you?

One of the big moments for me was what I call the insurrection today. I used to call it a riot in 1992. You know, the post-Rodney King incident, the impact of that. It was shocking to me. Because all of a sudden, I started to question the work that we were doing. I started to see that we, in policing, we were walking in one universe, and it was very different than the universe of the people that we were policing.

I used to view myself as the safe-keeper, the one that people can come to for help. But there was such a significant portion of our community that actually looked at us, and looked at what I stood for, as the aggressor — as the occupation army type.

There were other things too. When you work in these very vulnerable areas, life is short, right? When you get as old as I am, you start seeing the kids of the generation that you might have arrested before, and they’re going down the same way. And you have to stop and question yourself.

In those days, violence was way higher than it is today. The city of L.A. was recording 1,000 homicides a year. But one of the things that Father Greg Boyle [the founder and director of Homeboy Industries, the world’s largest gang-intervention and rehabilitation program] always used to say, in the darkest moments, was, "Every human being has a story, and every human being has a capacity to be better.”

When we start looking at people as human beings, and we understand that everyone has a story, and that everybody has the capacity to be better — some may never get there, but we have the capacity to — you [create] a system that begins to acknowledge that and hold people accountable. [A system] that ensures that those who are dangerous are segregated from the rest of us, but that those who are no longer dangerous are not.