Are Cambria’s pines in danger? Experts fight to heal forest amid drought, diseases

On a warm July morning, the Monterey pine forest surrounding Cambria was alive with sound: the faint buzzing of insects, chirps of nearby birds and crunching footsteps of an occasional deer navigating its way through the dense brush beneath the towering trees.

The morning fog had burned off by 10 a.m. and the day’s heat hadn’t quite hit yet.

Walking on a faint path on the privately owned Covell Ranch just west of the center of the San Luis Obispo County town of 5,700, Cal Fire and San Luis Obispo County Community Fire Safe Council officials stopped to point out a small grouping of Monterey pines.

“All of these are impacted right here,” Dan Turner, executive director of the Fire Safe Council, said.

He and Cal Fire Forestry Assistant Jonathan Gee walked up to the young trees — none more than 20 feet tall — and examined the western gall rust and mistletoe infections affecting them.

In some unmanaged areas of Cambria’s Monterey pine forest, one of five native stands of Monterey pine trees in the world, the majority of the trees have been impacted by disease.

Turner noted that some of the infected trees may make it to full maturity, albeit in stunted form, while others won’t survive another few years. A Monterey pine tree can be live 70 to 90 years.

Disease is not the only factor hurting the Monterey pine tree as an intense drought continues to grip the region and starve the forest of its need for a humid climate.

“This is a very unhealthy forest,” Turner said. “And we’re concerned about how rapidly a fire would burn through here.”

What’s the best way to make Monterey pine forest healthy?

Cal Fire, with grants from the Fire Safe Council and other state agencies, is working to reduce the wildfire risk in the area through targeted projects.

Hand crews equipped with chainsaws and wood chipping machines are thinning the forest by cutting down dead and diseased trees.

It’s a style of forest management that has earned some critics within the small community.

“That’s a serious problem because they’re just continuously reducing the number of trees,” said Crosby Swartz, chairman of the Cambria Forest Committee.

He believes that leaving the forest relatively untouched is the most natural and best path to managing the forest, noting that trees absorb carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and provide key wildlife habitat.

The Monterey pine tree is a fire-adapted species, meaning it normally needs heat generated from fires for its cones to open and disperse seeds — although the seeds can also open when the sun heats them enough.

“We’re at the point where a cultural burn is dangerous,” said Mona Tucker, tribal chair and member of the yak titʸu titʸu yak tiłhini, Northern Chumash Tribe.

The Chumash wouldn’t want burning “in areas with such high fuel content,” Tucker said.

Tucker said Native Americans may have historically conducted cultural burns in the Cambria area. However, she added, it’s difficult to tell exactly where and how those burns might have been conducted because white settlers wiped out most native peoples before Chumash burning practices were documented by anthropologists.

So, the stories passed down by the generations before her are the only evidence of any such activities, Tucker said.

The end goal in Cambria is to conduct prescribed burns, according to Turner and Gee. But that’s likely several years out because of the high amount of invasive plants and dead and diseased trees in much of the forest, they noted.

California State Parks has conducted small prescribed burns in the native Monterey pine forest in Hearst San Simeon State Park just north of Cambria, according to Katie Drexhage, a senior environmental scientist for the agency’s San Luis Obispo Coast District.

“We’re doing small burns in the understory to rejuvenate the seed bank,” she said, adding that the agency also cuts down dead and diseased trees in the park.

Cambria has history of halting natural fires

Many Cambria residents will tell you they moved to the area to escape from urban life and enjoy a tranquil existence amid the trees.

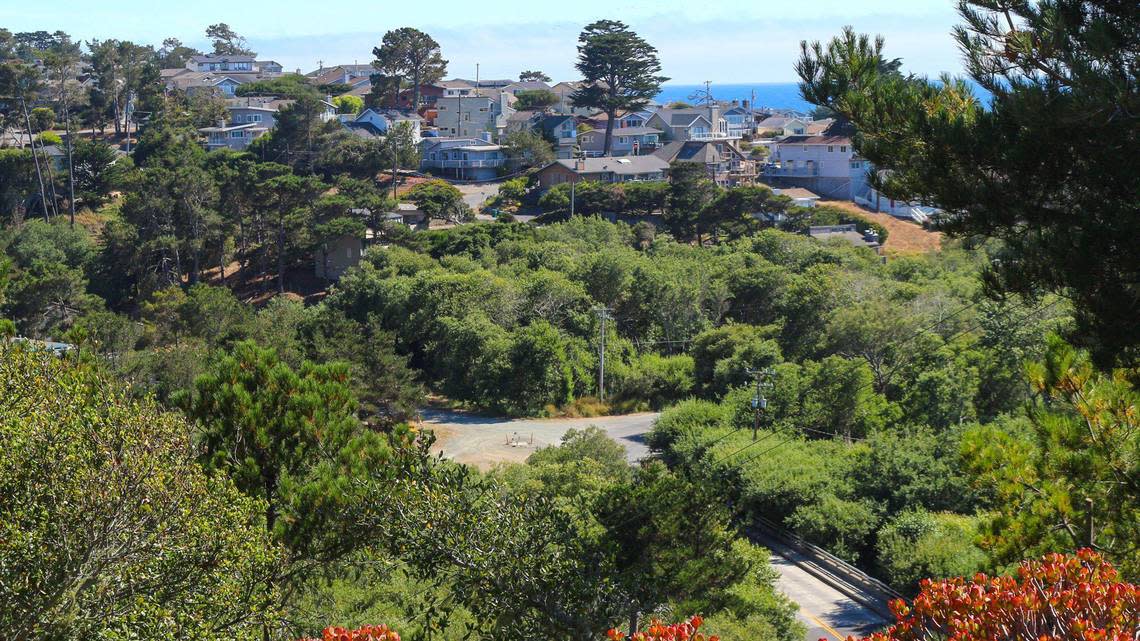

The town is nicknamed, aptly, Cambria Pines by the Sea. Many community members’ homes are tucked right into the dense forest, while others sit in grassy meadows lining cliffs that drop off into the Pacific Ocean.

Development of the North Coast town began in the late 1860s, and the majority of fires that have sparked since then have been put out as quickly as possible to avoid damage to homes and businesses.

This is a problem, Gee said.

“Monterey pines are fire dependent,” he said. “And yet we have excluded fire from it. It’s a natural process we have unnaturally stopped from happening.”

Fire suppression activities have allowed fire fuel — invasive plants and dead and diseased trees — to build up over the years, Gee said.

So-called “ladder fuels” — dry and extremely flammable brush in the forest’s understory, including invasive species such as French broom — put the forest at risk of a wildfire that would spread into the canopies of the Monterey pine trees. Such a blaze could kill those trees and be extremely dangerous to fight.

A wildfire typically needs a few factors to become as devastating as the 2018 Camp Fire, which destroyed nearly the entire town of Paradise: lots of dry fuel, high winds and hot temperatures.

However, it’s more likely that Cambria could experience something closer to the 1987 Morse Fire, which scorched a Monterey pine forest in Pebble Beach.

The Morse Fire started after an illegal campfire quickly got out of control in the Del Monte Forest. It ended up burning 160 acres, destroying 31 structures and injuring 15 firefighters and three civilians.

At the time, annual rainfall in Pebble Beach was 50 to 60% below average and winds were gusty, causing the flames to spread quickly from the forest into surrounding neighborhoods.

Climate change, disease causing trees to struggle

Turner and Gee said they see Cambria as having the “perfect” wildfire conditions if left unchecked.

During the most recent extreme period of drought in the region — 2012 to 2017 — a few pockets of Cambria’s forests saw more than 75% of the trees die, while most areas experienced mortality rates between 20 to 50%, according to Cal Poly data. The high mortality was linked to drought-stressed trees more susceptible to bark beetles, pine pitch canker and other diseases.

These dead trees, if not removed through Fire Safe Council and Cal Fire efforts, are drying out again after a brief respite from the drought.

Cambria received just 67% of its average annual rainfall during the 2021-22 rainfall season that ended on June 30.

As the Monterey pine trees die and fall, they’re slowly getting replaced by other species such as coast live oak and eucalyptus trees.

“This could turn into Cambria by the Oaks,” Turner remarked.

Anecdotally, residents say they’re seeing fewer foggy days during the summer. That’s backed up by data from UC Berkeley researchers who found in 2010 that fog frequency along portions of California’s coast had declined by 33% since the early 20th century.

High humidity helps dampen fire fuels. It can also feed the trees and plants by condensing on their needles and leaves and then dripping down onto the soil. Plus, the marine layer has abated much of the heat felt in the more central areas of the county.

Cambria is also a naturally windy area. Typically, the strongest winds experienced in the area — known to blow over trees and cause damage to homes and businesses — are accompanied by rain.

Data analyzed by now-retired PG&E meteorologist John Lindsey revealed that San Luis Obispo County appears to be getting windier. That’s due to climate change impacting offshore and onshore conditions and influencing the pressure systems that cause the wind to blow, Lindsey wrote in his “Weather Watch” column in June.

Different forest management tactics clash in Cambria

As conditions stand now, Turner sees the Monterey pine forest as desperately needing management to prevent a devastating wildfire.

“The forest wouldn’t be bothered by a fire,” he said. “The town, that’s another story. The fact that there’s a town in the middle of this forest, now that’s an issue.”

But just how to effectively manage the forest to prevent such an event is up for debate within Cambria’s boundaries.

Gee and Turner said Cal Fire is working to reduce the number of dead and diseased trees on the Covell Ranch property so the forest sits at about 200 trees per acre from roughly 500 trees per acre.

To do the work, the agency had to receive support from various entities including the California Coastal Commission; California Department of Fish and Wildlife; Nature Conservancy; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; California Native Plants Society and the Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District.

Turner said he’s grateful the work can be done on the Covell Ranch property.

Without it, he said, a massive wildfire potentially sparked by an illegal campfire could spread into the town. And no law mandates private property owners to do forest management to prevent such a disaster, he said.

“We’re 100% comfortable that this is what’s right for the forest,” Turner said of the work to cut down dead and diseased trees and remove invasive species. “We’re basically social distancing the trees to create a healthier, more resilient forest.”

Eventually, the goal is to do prescribed burning on the Covell Ranch property, he said.

That won’t happen until the fuels are reduced, Turner added.

Should preservation, planting be prioritized over cutting down trees?

Swartz of the Cambria Forest Committee is among a faction of Cambria’s population that believes the forest should be left relatively untouched by humans to not disturb its natural processes.

“Cal Fire considers everything in the forest, trees other vegetation, to be fire fuel,” Swartz said. “And so their approach is to try to cut down as many trees as they can, typically like half, and reduce all the vegetation that is associated with the forest.”

Greenspace Cambria, a nonprofit land conservation trust, used donations from the public to acquire lands within and around the town.

The organization has amassed a total of roughly 30 acres — with parcels ranging in size from small neighborhood lots to a 21-acre property called Strawberry Canyon.

Strawberry Canyon lines neighborhoods on the southern side of Cambria before stretching toward the ocean and the Kenneth Norris Rancho Marino Reserve.

The group’s president, John Seed, largely agrees with Swartz’s viewpoints on forest management.

“When you walk through Strawberry Canyon, you’re going to see the lifecycle of the Monterey pine,” he said. “You’ll see young, healthy ones coming up. You’ll see diseased ones that are turning brown that are going to be on their way down and you’ll see fallen trees.

“All of that is normal. ... And that’s the experience we want people to have. Here’s what a forest does when it’s left alone.”

Greenspace and the Forest Committee see Cambria’s Monterey pines as absolutely vital to the local ecosystem and carbon sequestration.

The trees’ decline in recent decades has them worried, so the groups work hard to plant native Monterey pines in and around Cambria.

Working with State Parks, Greenspace planted about 3,000 trees in Hearst San Simeon State Park in December 2019 and January 2020.

Of those, nearly 60% have survived, which left the organization “thrilled,” said Karin Argano, its director.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted its operations, Greenspace was selling between 200 and 250 Monterey tree seedlings grown from seeds gathered in the local forest. Those seedlings were primarily for property owners who needed to plant Monterey pines to offset any that were cut down for construction, fire mitigation or other reasons.

While Swartz agrees that fire risk is a huge concern for the community, he said, he believes that managing it doesn’t start in the forest.

“You need to start from the house out,” Swartz said. “In other words, you need to protect the house against blowing embers if there’s a fire nearby, and try to harden the house in other ways.”

Creating a defensible space around a home should be a no-brainer, he said, especially when living in Cambria’s Monterey pine forest.

Residents should create buffers around their homes of between 30 and 100 feet by removing fire fuels and keeping the grass cut low, according to Cal Fire, which has a guide on its website for creating defensible spaces.

“Once you get beyond that, there’s not really that much else you can do,” Swartz said. “These big, hot, dry wind-driven fires are almost impossible to control and you can do things to try to prevent them from being ignited in the first place.”

Tending forest is key to water quality

Carefully tending the forest is key not only to fire management but improving groundwater quality and infiltration, said Devin Best, executive director of the Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District.

“If you’re working on the health of the forest and it leads to improved water retention, improved forage, improved wildlife habitat ... eventually, when you look down in the creek, there’s more water available because you’re managing things differently,” he said.

Preserving a forest in its natural condition makes sense, Best said, but ensuring there aren’t risks to infrastructure should a fire spark is also key.

“Yes, let’s preserve as much as we can, but in those instances where there’s risk to infrastructure, people’s well being or it would improve the forest ecology by going in and doing something, then that’s where we feel like we are on the other side of things,” Best said. “So if we need to do something, we can’t just let it sit here and let it essentially catch on fire and burn up completely.”