California agrees to $2 billion settlement over Covid pandemic learning loss for struggling students

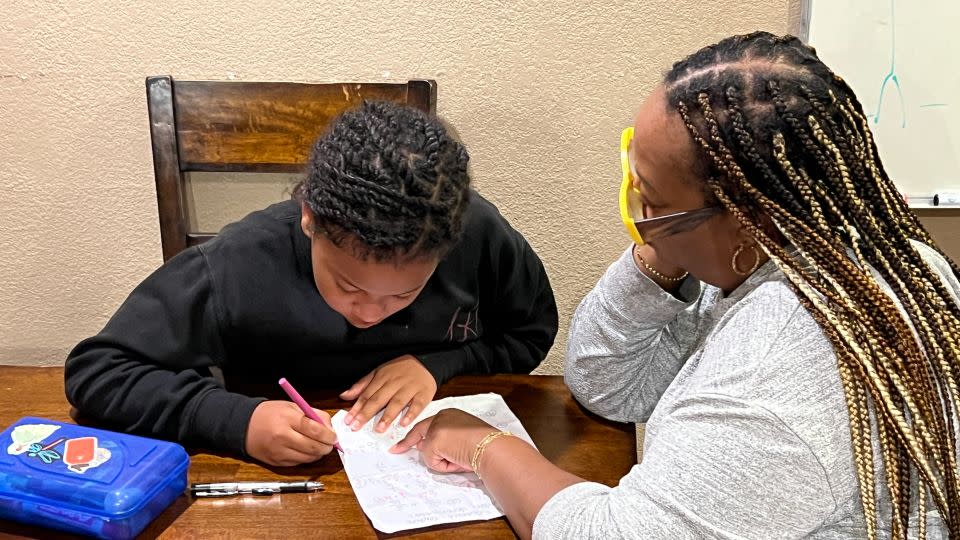

“I’m not getting a fat check!” joked Kelly R as she helped her daughters with homework in the kitchen of their Los Angeles home. “But I’m hoping that the kids will benefit. That’s the biggest thing that I was worried about. All kids benefitting.”

Kelly is among the parents, students and community groups who successfully sued California, demanding more money, time and focus be spent to help underserved students – disproportionately low-income Black and Latino kids – recover from educational losses during the Covid pandemic. These students were already at a disadvantage before the pandemic, according to experts, then suffered more than students in affluent school districts during Covid and are not rebounding as quickly.

The plaintiffs were only identified by first name and last initial in the lawsuit, and Kelly asked CNN to do the same.

Kelly, like so many other parents, does not have fond memories of virtual schooling. She was stuck at home with her daughters who were ages 9, 11 and 14 when the pandemic began.

“The computers were glitchy…We live in the airport flight paths; sometimes we weren’t getting internet connection. Sometimes the school Internet connection … wasn’t working as well,” she told CNN. “We were kind of just thrown into a situation to be teachers for three different kids, you know, at three different schools … with no training at all.”

To settle the lawsuit, California agreed to spend $2 billion to help children impacted the most to recover from lost learning and the mental health impact caused by school closures during the pandemic. The federal government granted public school districts more than $190 billion between March 2020 and March 2021 for that purpose, but the plaintiffs argued that in California the state failed to ensure local districts targeted the money for students who needed the most help.

The settlement’s provisions still must be enacted into law by the state legislature, directs school districts to use extended school days, tutors and mental health professionals to help these kids. The process will be closely monitored by the state. And parents can file complaints at any time.

“This proposal includes changes that the Administration believes are appropriate at this stage coming out of the pandemic to focus use of these one-time dollars… on the students who were most impacted and continue to need support,” Alex Traverso, a spokesperson for the California Board of Education, told CNN.

“It is the most urgent crisis in America today,” said Mark Rosenbaum, a lawyer for the plaintiffs. “And hopefully this settlement will be a model for 49 other states to say that there is nothing more important than we can do.”

In California, around 10,000 public schools were closed during the pandemic, impacting around 6 million students.

“We know in California that there were between 800,000 and a million kids who had no digital access whatsoever for 18 and 19 months,” said Rosenbaum. “What does that mean? It doesn’t mean they got bad education. It means they got no education.”

And there were other problems. Plaintiffs Cayla and Kai were second graders in Oakland when Covid hit. “Between March 17, 2020 and the end of the 2019-2020 school year, their teacher held class only twice,” the complaint alleges.

They and other plaintiffs reported a lack of computer equipment, broken equipment and teachers not trained to cope with the technology or the challenges of remote learning. Plaintiff Ellori was in first grade during the 2020-2021 school year and, with 33 kids and just one teacher on Zoom, felt “isolation, abandonment and anxiety.”

Not enough has been done since the pandemic ended to assess students’ needs and help them recover lost learning, according to the lawsuit. Jordan, another plaintiff, was in elementary school in the spring of 2020 when the school closed, according to the plaintiffs.

“Since returning to in-person instruction in the 2021-2022 school year, Jordan E. has not had an assessment of his learning or mental health needs,” according to the suit, referring to the 2021-22 school year.

School-age children were among those with the lowest risk of serious illness from Covid-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But they suffered greatly from the restrictions to stem the spread of the virus because so many schools were closed for so long.

“And essentially we’re asking poor kids to pay for the public health measures that were meant to, you know, benefit us all,” said Thomas Kane, a professor at Harvard University and author of a new study tracking post-pandemic progress in education.

The average American public school student in grades 3 through 8 lost half a grade level in math achievement during the pandemic, according to Kane and his fellow researchers at Harvard, Stanford and Dartmouth Universities. Their Education Recovery Scorecard also found a third-of-a-year drop in reading.

Some students are rebounding surprisingly well, they say. But not all.

In Alabama, for example, kids in some more affluent areas have already made up for all their lost learning in math, Kane says.

“But the higher poverty districts like Montgomery are still a half a year or more behind,” Kane told CNN. “Here in Massachusetts, the high poverty districts did the opposite of catching up last year, they actually lost additional ground” between 2022 and 2023.

The fear, say these researchers, is that some students might never catch up.

Kelly says her kids are still behind in math.

“In-person tutoring would be beneficial for the kids,” she said after patiently helping her 5th grader with some arithmetic at the kitchen table. Right now, she said, “They do online tutoring. Sometimes.”

Kelly says she’s trying to fill the gap and is pretty good at “1980s math” but doesn’t know how to teach the subject as it’s taught today.

Black, Latino and low-income students have traditionally lagged behind White students in academic achievement.

Kelly hopes this suit and settlement will spur the country into addressing, once and for all, the historic inequities.

“That’s one of the major reasons why I felt like this was important,” she said. “Because we cannot continue to let things like this happen and let our kids fall short.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com