Homeowners sue L.A. for right to demolish Marilyn Monroe's house

In January, fans and conservationists celebrated when the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission recommended landmark status for Marilyn Monroe’s home, a crucial step in saving the residence from being demolished.

The new owners of the Brentwood property were less ecstatic. They sued the city of L.A. on Monday for the right to demolish it, claiming that city officials acted unconstitutionally in their efforts to designate the home as a landmark and accusing them of “backdoor machinations” in trying to preserve a house that doesn’t meet the criteria for status as a historic cultural monument.

The lawsuit comes from heiress Brinah Milstein and her husband, reality TV producer Roy Bank, who bought the Spanish Colonial-style home last summer for $8.35 million and immediately laid out plans to raze it. They owned the house next door and hoped to combine the two properties to expand their place, according to the lawsuit.

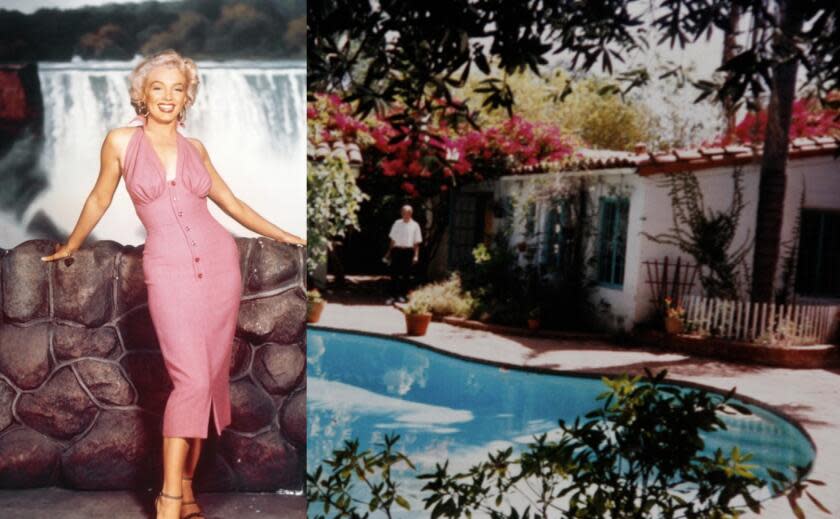

Monroe bought the house in 1962 for $75,000 and died there six months later after an apparent overdose at the age of 36. The phrase “Cursum Perficio” — Latin for “The journey ends here” — was adorned in tile on the front porch, though its origin is a mystery.

Fans and conservationists claim the residence is a part of Hollywood history and a physical reminder of Monroe’s legacy.

Milstein and Bank disagree. Their lawsuit claims that the home has had 14 owners since Monroe’s death and has been substantially altered, with over a dozen permits issued for various remodels over the last 60 years.

“There is not a single piece of the house that includes any physical evidence that Ms. Monroe ever spent a day at the house, not a piece of furniture, not a paint chip, not a carpet, nothing,” the lawsuit says.

The house isn’t visible from the street, but that hasn’t stopped it from becoming a tourist hot spot. Fans and tour buses flock to the property to snap pictures of the privacy wall, which the lawsuit claims is a nuisance to the neighborhood.

The battle over the home has been brewing since September 2023, when the city issued a demolition permit to Milstein and Bank on Sept. 7. The public outcry was swift, and L.A. City Councilmember Traci Park said she received hundreds of emails and phone calls urging her office to initiate the process of declaring the home a historic cultural monument in order to save it.

Park held a news conference titled “Marilyn Monroe Home Preservation” the next day, delivering an impassioned speech while wearing red lipstick and short blond hair in a nod to Monroe.

After the speech, the City Council voted to begin the landmark consideration process, nullifying the demolition permits. The council will vote to officially on whether to declare the house a historic cultural monument this summer.

The goal of the lawsuit is to cancel that vote and restore the right to demolish the property.

While addressing the Cultural Heritage Commission in January, Milstein suggested relocating the home rather than designating it a landmark. It’s unclear whether that option is still possible.

“In the eight years that we have lived next door, we have seen the property change owners two times,” Milstein said while addressing the commission. “We have watched it go unmaintained and unkept. We purchased the property because it is within feet of ours. And it is not a historic cultural monument.”

The process of protecting potentially historic homes has been a hot topic in recent weeks. It most recently surfaced when Chris Pratt and Katherine Schwarzenegger demolished the Zimmerman House, a beloved Midcentury home designed by Craig Ellwood, to build a modern mansion in its place.

The demolition sparked an outcry among locals and architecture enthusiasts, who questioned why the city allowed the Midcentury “time capsule” to be torn down.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.