Bannon's been cited for contempt of Congress. But will he ever be forced to cooperate with the Jan. 6 probe?

The House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol faces a major test of its subpoena powers as the Justice Department considers whether to prosecute former Trump aide Steve Bannon for criminal contempt of Congress.

Members of the select committee have repeatedly warned that there will be serious consequences for anyone who refuses to comply with subpoenas for testimony or documents with relevant information about the storming of the Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump, and the events leading up to it.

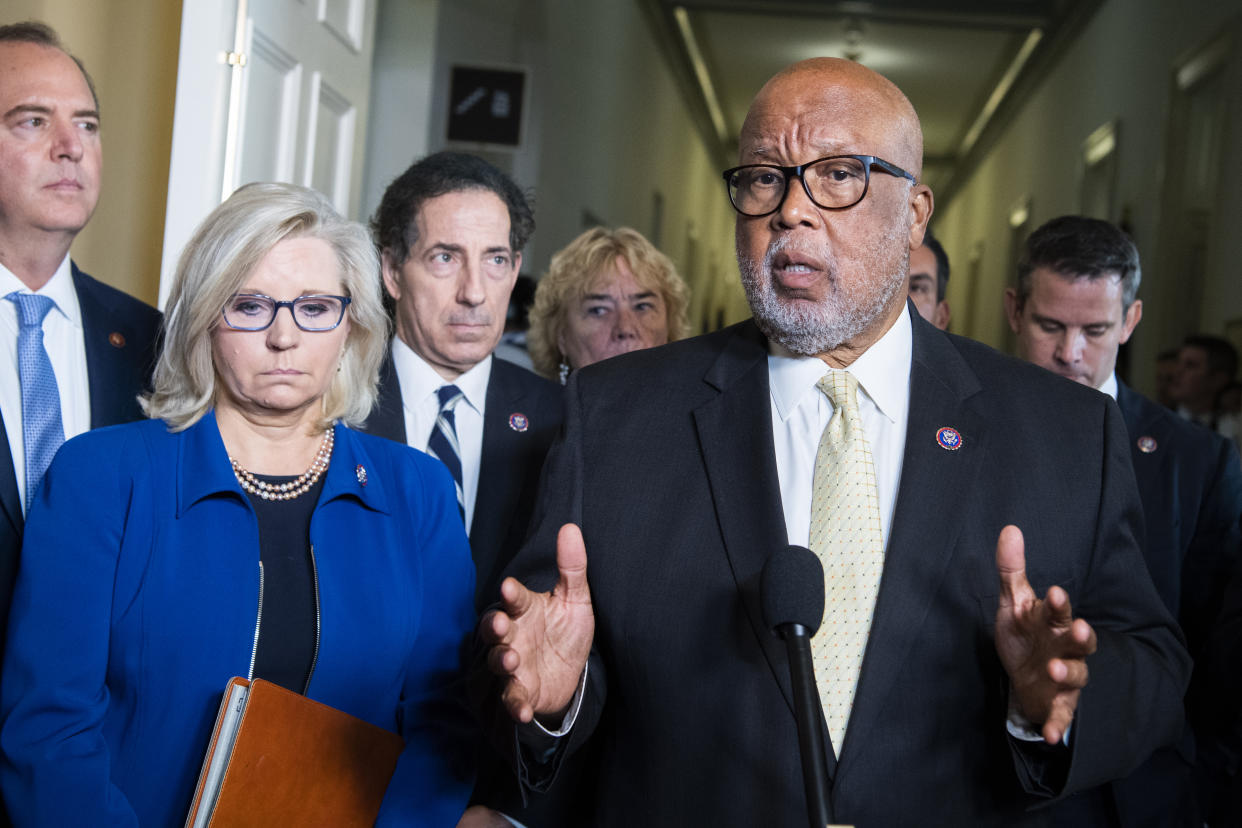

“The Select Committee will not tolerate defiance of our subpoenas,” the committee’s chairman, Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., said in a statement earlier this month, insisting that “witnesses who try to stonewall the Select Committee will not succeed.”

But days after the House of Representatives voted to cite Bannon for criminal contempt of Congress for doing just that, it remains unclear what more, if anything, will be done to compel him — or anyone else — to cooperate with the probe going forward.

It is now effectively up to the Justice Department to decide whether to present the House’s contempt citation before a grand jury. If that happens and Bannon is indicted, he’ll face a trial in district court and, if found guilty, up to one year in prison and a maximum fine of $100,000. But prosecutions for such cases have historically been rare and convictions even rarer. The last person found guilty of criminal contempt of Congress was Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy in 1974.

The last person to go to trial for contempt of Congress was Rita Lavelle, a former Environmental Protection Agency official in the Reagan administration. In 1983, Lavelle was indicted by a grand jury eight days after the House of Representatives cited her for contempt of Congress for refusing to comply with a subpoena from the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which ordered her to appear at an investigative hearing.

“She did the same thing Bannon did, she just didn’t show up,” said former House counsel Stan Brand, who helped build the criminal contempt case against Lavelle. Brand spoke to Yahoo News about some of the similarities between the 1983 case and the one currently being considered by the Justice Department, and the limits of Congress’s authority to hold recalcitrant witnesses to account.

Like Lavelle, Bannon failed to appear for a deposition and turn over documents sought by the select committee by the deadlines set in his subpoena. Both had already been fired from their government jobs by the time they were subpoenaed. But while the former EPA official argued that physical and mental health issues had prevented her from testifying, Bannon, who served as Trump’s chief strategist during the 2016 campaign and then worked in the White House for several months, has cited the former president’s claims of executive privilege over his testimony.

The executive privilege defense presents a significant hurdle for the Justice Department, which has previously declined to prosecute officials for withholding information from Congress when the president has invoked this power. That doesn’t mean Bannon, a private citizen who hadn’t worked in the White House for years at the time of the Jan. 6 attack, will automatically be exempt from prosecution, nor do the unique circumstances of his case guarantee he’ll go to trial.

Even if Bannon is indicted, the government will have to prove he knowingly and willfully defied his subpoena without an excuse, something Brand and others on the Lavelle case failed to do. Though the House had voted 413-0 to hold Lavelle in contempt of Congress, the jury in the criminal case decided to acquit her after two days of testimony.

“That was the end of that,” Brand said. “They never re-subpoenaed her.”

At the time, Brand called the verdict in the Lavelle case “a setback for the House to enforce its subpoenas” and told the Washington Post, “We are just going to have to arrest people and try them in the well of the House."

Brand was referring to Congress’s “inherent contempt” authority, which allows the House and Senate to levy fines and even arrest and detain witnesses who fail to comply with a subpoena or otherwise “obstruct the performance of the duties of the legislature.” Though the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld Congress’s inherent contempt power, it has not been used since before World War II.

In the last few years, some House Democrats have advocated for a revival of inherent contempt as a means of penalizing uncooperative Trump administration witnesses for failing to comply with requests for testimony or documents in relation to various investigative efforts. Recently, lawmakers have raised the possibility of invoking this long-dormant congressional authority to enforce subpoenas issued by the Jan. 6 select committee. In September, Politico reported that House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer said inherent contempt “is on the table and will remain on the table.”

In an appearance on MSNBC earlier this month, select committee member Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., also suggested that the House might use its own inherent powers to sanction witnesses who defy subpoenas. “I don’t think anybody should be testing our patience,” Raskin warned.

A spokesperson for the select committee declined to comment on whether it is considering invoking inherent contempt in the event that Bannon is not indicted on criminal contempt charges. Brand predicted that such a drastic move would be unlikely, given the potential for political backlash against the committee.

“I just don’t see that happening,” he said, suggesting that if Republicans had not blocked the creation of an independent commission to investigate Jan. 6, such a panel might have had a better chance compelling Trump allies like Bannon to testify than the Democrat-led House select committee. At the very least, he said, an independent panel would have been “insulated from the cries of partisanship.”

Still, whether Bannon is indicted by a grand jury, arrested by the House sergeant-at-arms or — in what many experts say is the most likely scenario — forced to defend himself in a civil lawsuit that could take years to litigate, Brand said, “At some point you have to go to court.” Ultimately, the threat of contempt may be more effective at compelling witnesses to cooperate with congressional investigations than the law itself. Brand noted that Congress has struggled in the past to enforce its subpoena power, losing many cases on appeal.

“If you look at the history of the congressional contempt statute in terms of its enforceability, it’s abysmal,” he said. “It’s not as great a power as people think.”

____

Read more from Yahoo News: