How the Allman Brothers made Jimmy Carter president, according to new rock history

On Nov. 2, 1972, the Allman Brothers Band made their live debut with a new lineup. Duane Allman, the band’s transcendent guitarist and leader, had died a year earlier in a motorcycle accident. His place, as if anyone could fill it, was taken by 20-year-old wunderkind Chuck Leavell, one of rock’s greatest pianists. The group was locked in.

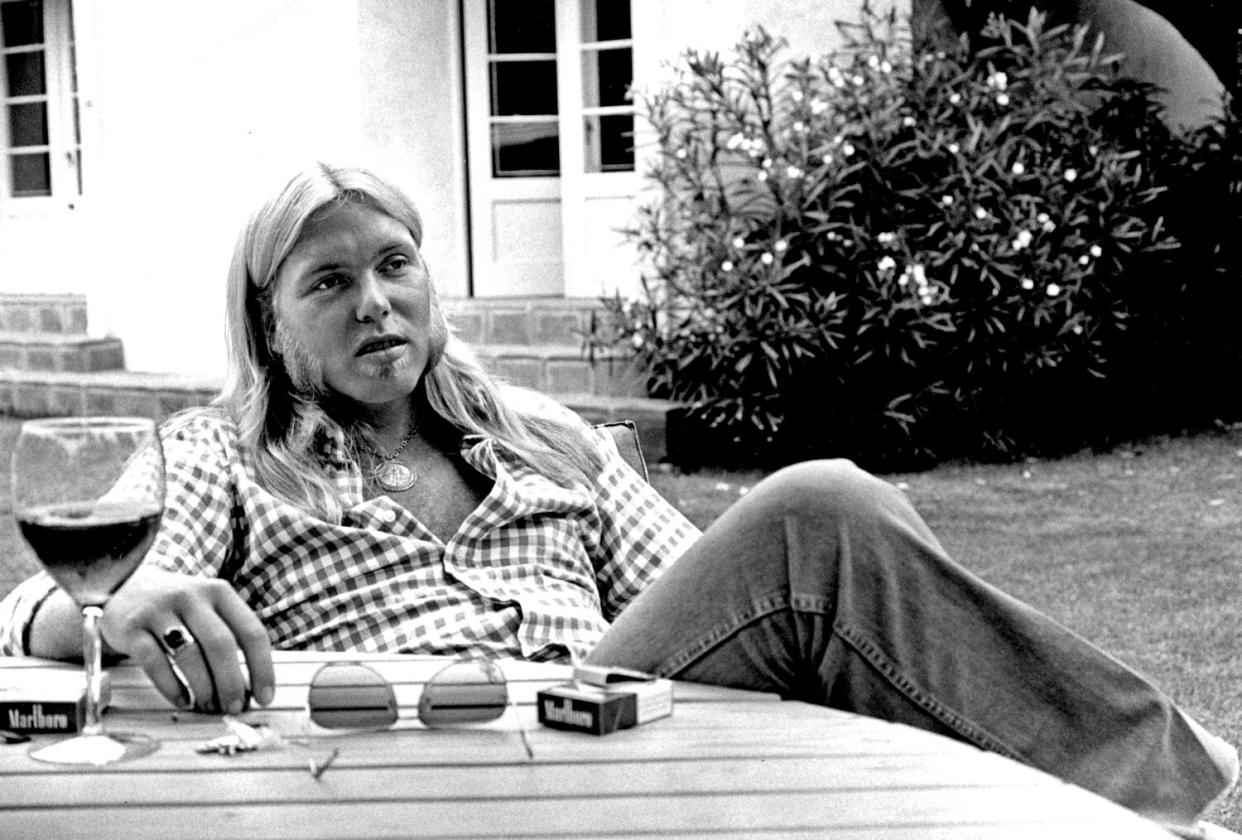

Playing as part of Don Kirshner’s “In Concert” TV show along with Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chuck Berry and Poco, the Allman Brothers premiered “Ramblin’ Man.” The song, a tasty slice of country rock fueled by Dickey Betts’ twangy guitar, would go on to become the band’s highest charting single at No. 2. With it and Gregg Allman’s “Wasted Words” already in the can for their next album, one of America’s greatest jam bands saw nothing but blue skies ahead.

Then tragedy struck — again. Just nine days after the taping, Berry Oakley, the adventurous bassist whose innovative playing helped the band's music take flight, also died in a motorcycle crash.

Losing two key members in such close succession would be more than enough to destroy most bands. But as author Alan Paul convincingly argues, the Allman Brothers weren’t like most bands. They were stronger, better and more resilient, at least for a while. In his engaging new book, “Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album that Defined the ’70s,” Paul depicts the band barreling through substance abuse, death and despair to make their biggest selling record and become America’s most popular band — before it all finally comes crashing down.

Read more:It was all a blur: How guitarist Graham Coxon (barely) survived Britpop, in a memoir

Along the way, Paul takes several interesting detours. He shows how the Allmans inspired the Southern Rock movement, paving the way for the likes of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Marshall Tucker Band. He also takes readers behind the scenes of July 1973’s Summer Jam at Watkins Glen, N.Y., the largest rock festival ever with 600,000 fans, which the Allman Brothers co-headlined with their friends the Grateful Dead.

“The Allman Brothers Band elevated above their rock and roll peers to become an American institution ... a group that birthed a genre, had immense impact on country music, helped elect an American president, and stood at the center of the nation’s culture,” writes Paul, also the author of the best-selling “One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.”

In Paul’s telling, the process of making “Brothers and Sisters” was anything but smooth. Gregg Allman was working on his first solo album, “Laid Back,” at the same time. Betts began to assume leadership of the band, creating tension between him and an increasingly drug-addled Allman. Integrating Leavell and new bassist Lamar Williams into the Brotherhood proved challenging.

Somehow, they managed to produce a multiplatinum album with a mellower and more accessible sound, including the upbeat instrumental “Jessica,” which later won a Grammy Award. The band’s timing couldn’t have been any better.

“The vibe on ‘Brothers and Sisters’ was unknowingly tapping into a national mood,” Paul writes. “The country sought tranquility, togetherness, and a simpler, more peaceful time after being torn apart in the ’60s by social upheaval.”

Fueled by the popularity of “Ramblin’ Man,” “Brothers and Sisters” would go on to sell 7 million copies. It landed the Allman Brothers on the cover of Rolling Stone. It made them superstars. Perhaps most interestingly, their success caught the attention of a peanut farmer from Plains, Ga., who dreamed of becoming president.

In January 1974, Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter held a post-show party at the governor’s mansion for Bob Dylan and the Band. Because of his relationship with Allman Brothers manager Phil Walden, Carter also invited the group.

Read more:Jann Wenner didn't like his biography. So he wrote a memoir

Gregg Allman showed up late, after everyone had left. Instead of being turned away, he found himself alone on a porch with Carter drinking J&B scotch and listening to records by bluesman Elmore James. Carter started reeling off lyrics to “Midnight Rider” and other songs Allman had written. The governor told the singer that he was running for president and might one day need some financial help.

Allman liked Carter but thought the Levi’s- and T-shirt-clad man seated next to him had no chance. But Carter, like the Allman Brothers, repeatedly defied the odds. On Nov. 25, 1975, the band played a benefit for the cash-strapped candidate at the Providence Civic Center in Rhode Island. The group not only raised money for Carter but, as Paul notes, also burnished his image with young voters.

“If it hadn’t been for Gregg Allman, I never would have been president,” Carter said.

But as the peanut farmer ascended, the Allmans went the other way. Drugs, infighting and exhaustion took their toll. Their once-magical improvisations became self-indulgent and meandering, especially live. The band called it quits in 1976. Then reunited in 1978. Then broke up in 1982. Then got back together in 1989. Put out three strong albums in the 1990s. Pushed Betts out of the band in 2000 and soldiered on until 2014. There’s a book in there somewhere.

Read more:How millennials came to unironically love yacht-rock kings Steely Dan

For all its strengths, “Brothers and Sisters” drags at times, notably Paul’s description of Gregg Allman’s relationship with Cher, which seems better suited for the pages of the National Enquirer. The book also overstates the influence of the album itself. It's easy to argue that 1972’s “Exile on Main Street” by the Rolling Stones, Stevie Wonder's “Innervisions” (1973) and 1977’s “Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols” all left a bigger musical and cultural imprint.

Still, these are minor quibbles. Few writers understand or appreciate the Allman Brothers as much as Paul. His book, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of its namesake album, colorfully narrates an oft-overlooked chapter in the band’s history with nuance, clarity and perspicacity. In addition to his own extensive reporting, Paul had access to hundreds of hours of interviews conducted in the mid-1980s by Kirk West, a longtime Allman Brothers insider, for a book West never got around to writing. That material gives Paul’s work a real richness and depth.

“Brothers and Sisters” is a very good read for anyone interested in the Allman Brothers, the sounds of the ’70s or simply great music. It rocks.

Ballon, a former Times and Forbes reporter, teaches an advanced writing class at USC. He lives in Fullerton.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter to get the latest Los Angeles book news, events and more.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.