Neurodivergent students communicate differently. Their mental health improves when adults learn to listen.

A 6-year-old was scolded by his school bus driver for his “naughty behavior.”

An 11-year-old put his hands over his ears and screamed on the stage during his school’s fifth-grade promotion ceremony.

A 15-year-old girl cried, fell asleep in class and had frequent meltdowns.

All these students are neurodivergent.

For generations, adults have responded to neurodivergent children’s behaviors by ignoring them or punishing them, in an effort to stop behaviors they perceive as stubborn, defiant and disruptive.

However, as understanding of the brain has improved over the past several years and neurodivergent people have been empowered to advocate for themselves, things are changing. Now, parents and teachers are encouraged to dig below the surface of neurodivergent kids’ behaviors to understand what they are communicating.

The 6-year-old who acted out on the school bus wasn't alone. But his peers better understood social cues so they were able to be more subtle about their behavior, avoiding punishment.

The 11-year-old, who is autistic and has a language processing disorder, was overwhelmed by the noise as the audience applauded around him. And his classroom aide didn’t give him the noise-canceling headphones he needed.

The 15-year-old, who is autistic and has a developmental disability, was trying to communicate that she had been sexually abused.

As part of our Kids in Crisis series, we talked to young people, parents, educators and advocates to learn how these and other neurodivergent students' mental health can be supported, and interviewed experts and reviewed research about past educational practices and new models for supporting neurodivergent children.

'Kids aren't broken. They don't need to be fixed.'

Neurodivergent people's brains work differently than those of neurotypical people for a number of reasons, some of which are the result of diagnosable conditions such as autism, ADHD, language processing disorders and a handful of specific learning disabilities. Because of those differences, neurodivergent students often react differently to the world than their neurotypical peers do.

For example, hypersensitivity to certain sensory experiences can cause them to have difficulty controlling how they express their emotions, resulting in meltdowns or an inability to pay attention in class. Or a language processing disorder can make it difficult to answer open-ended questions about what they’ve read, making it seem as if they didn’t do their homework. Or their hyperfixation on specific interests can cause them to continue info-dumping when their teacher or classmate would prefer to change the subject.

Until recently, the accepted way to deal with those behaviors was to attempt to extinguish them. The child experiencing an emotional meltdown would be isolated in a separate room. The child who couldn’t answer unprompted questions would have to stay in from recess to do an assignment they’d already completed. And the child with a hyperfixation or special interest was told that school wasn’t the time or place to talk so much about passions other people didn’t share.

However, a better understanding of neurology has revealed key misconceptions under the previous model. First, neurodivergent kids do not choose their behaviors in an attempt to anger, disturb or annoy others. Many behaviors are attempts to communicate that their needs are not being met. Some behaviors, like running away or head-banging, can cause physical injuries and should be addressed with compassion. But most behaviors aren't harmful at all, just different.

Second, neurodivergent diagnoses have often been defined by deficiencies, ignoring that there are also strengths involved. For example, hypersensitivity to sensory stimulus can cause pain and emotional dysregulation for a neurodivergent person, but it can also make them more detail-oriented in ways that enhance their lives.

Third, necessary accommodations — such as noise-canceling headphones, fidget gadgets and comfort objects — have often been characterized as temporary necessities that neurodivergent children should eventually grow out of. But people don't grow out of being neurodivergent, and an environment that accepts accommodations for people's needsresults in happier and healthier people who are better able to maximize their strengths.

Katie Berg is the statewide coordinator for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction's Supporting Neurodiverse Students Professional Learning System.

“When I first started in the field of special education, we looked at compliance as key, and we were driven by trying to fit kids into the mold of a typical student," she said. "Now we’ve switched to working to recognize, understand and honor everyone’s differences.

“Our mindset now is that kids aren’t broken. They don’t need to be fixed. We need to accommodate and support them as best as possible.”

Creating spaces where neurodivergent people don't have to mask their passions

August Carlson was diagnosed with ADHD when they were in middle school. The diagnosis followed years of difficulty paying attention in class, often because they were hyperfixated on whatever their special area of interest was at the time.

Looking back, Carlson, who is now 22, recalls feeling like they were perceived as “hyper and loud and annoying.”

“There are so many times where a neurodivergent person has an experience of expressing their joy about something, and then they’re told, ‘you are being so loud right now’ or ‘you are too excited’ or ‘your interest is strange,’” Carlson said. “It’s a very othering experience, and you feel this sort of crushing shame and guilt.”

An internalized feeling of shame for being different is a common experience for neurodivergent people, and it often leads to masking — when neurodivergent people attempt to hide some of their traits. Studies show that neurodivergent people's efforts to mask their differences to "appear more neurotypical are associated with exhaustion, burnout, anxiety, depression, stress, reduced well-being, and suicidality."

Today Carlson facilitates a group of neurodivergent teenagers and young adults through their work with Islands of Brilliance, a Milwaukee-based nonprofit that provides learning experiences for autistic young people focused on their own special interests.

At meetings of Carlson’s Islands of Brilliance group in Eau Claire, participants are given prompts to create art projects. Carlson said the young people's projects are creative and expressive, but it’s the casual conversations that really stand out.

“The connection and social interaction has been the most important parts of these sessions,” Carlson said. “It’s so fulfilling to see the space so quickly become so comfortable for the participants, where they can express their special interests and what makes them passionate.”

Building acceptance and empathy into the classroom

Excitement about special interests isn’t the only trait that neurodivergent children frequently mask. Autistic people often do things like flap their hands, repeat sounds they hear or rock back and forth to cope with a sensory environment that can feel overwhelming. This is known as "stimming," and it’s another behavior that adults have previously sought to suppress in neurodivergent children.

The idea was that these types of behaviors made children look different, and if they could suppress them, they would fit in better with their peers. However, according to a 2019 study in the Journal of Early Intervention, "autistic adults report that stimming provides a soothing rhythm that helps them cope with distorted or overstimulating perception and resultant distress and can help manage uncertainty and anxiety."

Rather than try to change neurodivergent people by taking away their natural coping mechanisms, new approaches focus on educating neurotypical people so they understand and accept why neurodivergent people might act differently.

More: What is autism spectrum disorder? How to support the community this Autism Acceptance Month

That’s what Chelsea Budde and Denise Schamens set out to do when they started Good Friend Inc., a Wisconsin nonprofit that facilitates programs in schools to teach kids and teachers about neurodivergence.

"When my son, who is neurodivergent, was young, I was very concerned about him moving to kindergarten with 5-year-olds who didn't know what different brain wiring meant," Budde said. "I wanted to explain to his classmates the differences in how brains work, but I received pushback, and that's why we started Good Friend."

Good Friend creates videos, trainings and programs that teach students and staff about brain differences, autism and neurodivergence in an effort to equip neurotypical people with the ability to build positive relationships with neurodivergent people.

"At the end of the day, we need to find ways to communicate why our kids are different," Budde said. "Because their peers notice, and they can make up stories that aren't always kind."

Alison Peetz, whose now-adult son, Ben, has autism and a language processing disorder, said adults need to lead the way to encourage empathy at school. Although Peetz became a fierce advocate for her son as he progressed through school, she didn’t understand as much about the way neurodivergent brains work when he was a young child.

When Ben's emotions became dysregulated, he would sometimes fall on the floor and roll around. Teachers perceived his behavior to be tantrums and would report back to his parents each day about his “bad choices.”

“I have so much regret about this now, but we went along with the idea that if he made a ‘bad choice’ at school that he wouldn’t be able to watch TV at home,” Peetz said.

Ben’s classmates knew his at-home punishment and teased him about it, taunting, "You’re going to lose TV tonight."

“Knowing what I do now, he wasn’t equipped with the tools to make ‘good choices,’ whatever that means, so he was set up for failure," Peetz said.

Universal Design for Learning: Everybody benefits when they understand their emotions

"Behavior is communication" is a common refrain among educators and advocates who are well-versed in neurodiversity. It takes practice to understand what any person — neurodivergent or neurotypical — is trying to communicate with their behavior. And it's a skill that staff in many Wisconsin school districts have honed with the help of Enhancing Social and Emotional Skills in Students with IEPs (ES3) grants.

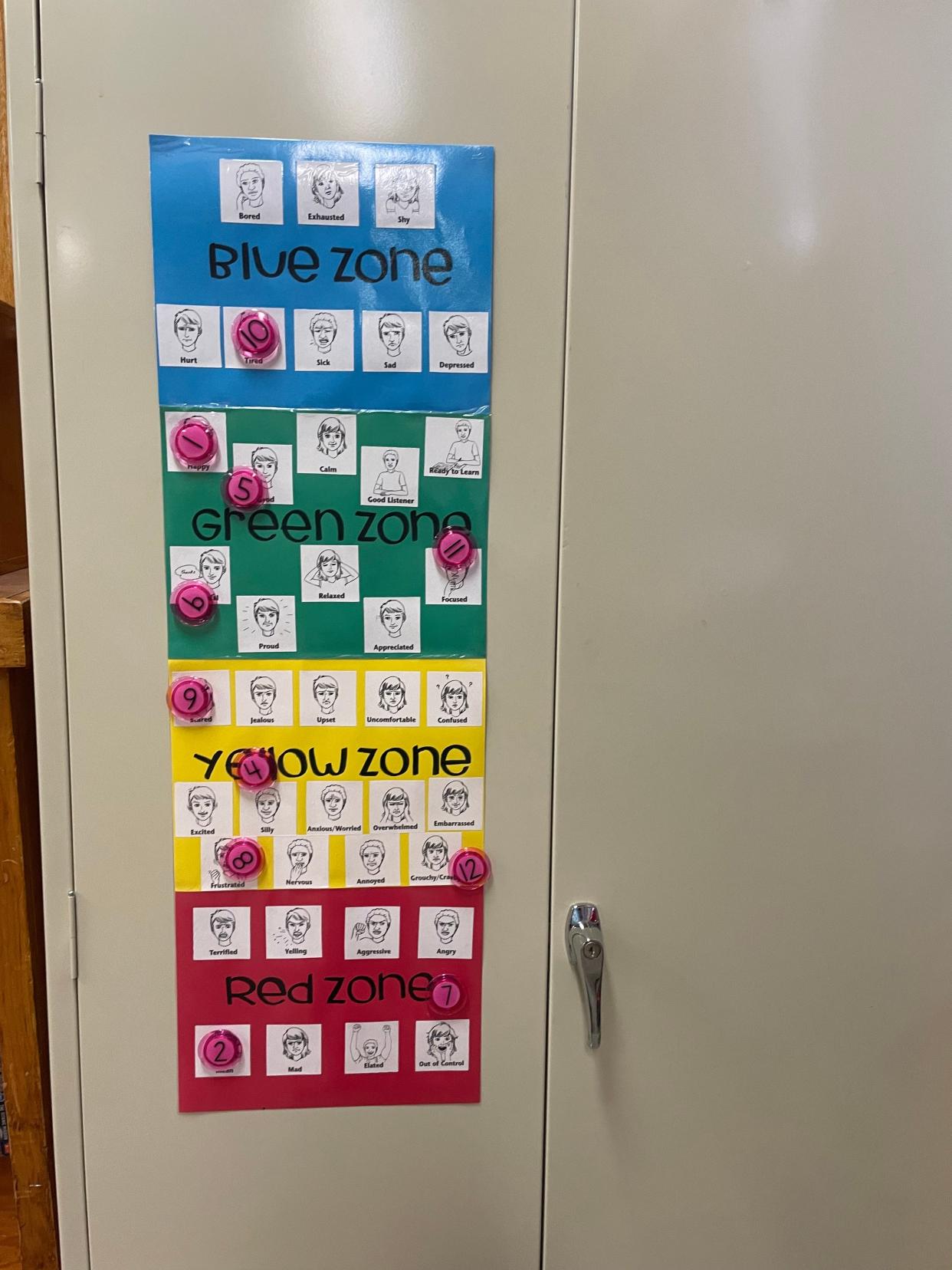

Several districts that have been part of the ES3 grant have implemented a program called Zones of Regulation. Through the program, everybody — adults and children — learns to identify their feelings and assign a color to them.

According to the Zones of Regulation curriculum, people are in the red zone when they are feeling intense emotions that might be overwhelming, such as anger, terror or elation. The blue zone means the person is feeling emotions that can deplete their energy, like sadness, fatigue or boredom. People in the yellow zone are starting to feel their emotions get stronger and their energy levels increase; feeling stressed, excited, frustrated or silly typically fits in this zone. And people in the green zone are generally feeling calm and alert, with emotions like happy, content, proud and focused.

"We teach students that no area of regulation is a bad zone and that everybody — adults, too — goes through many or all of the zones every day," said Rachel Kaderabek, a special education coach with CESA 7. "We can feel tired in the blue zone or frustrated in the yellow zone, but what's so important to model for kids is that we can use coping mechanisms to feel more regulated."

Teachers check in with students throughout the school day — often during natural transition times such as after recess or before going home — to ask what zone everybody is in. And, at any time, if a student is feeling dysregulated, they can tell the teacher, at which point they can use coping strategies they've learned to get them to a more "ready to learn" state.

"We have a lot of visuals on the wall to show all these wonderful coping strategies of 'here's what I'm feeling, what can I do to get to the green zone?'" said Kelli Palecek, a school counselor with the Trevor-Wilmot district. "We can do things like wall pushups, deep breathing, using a fidget tool, getting a drink or taking a break."

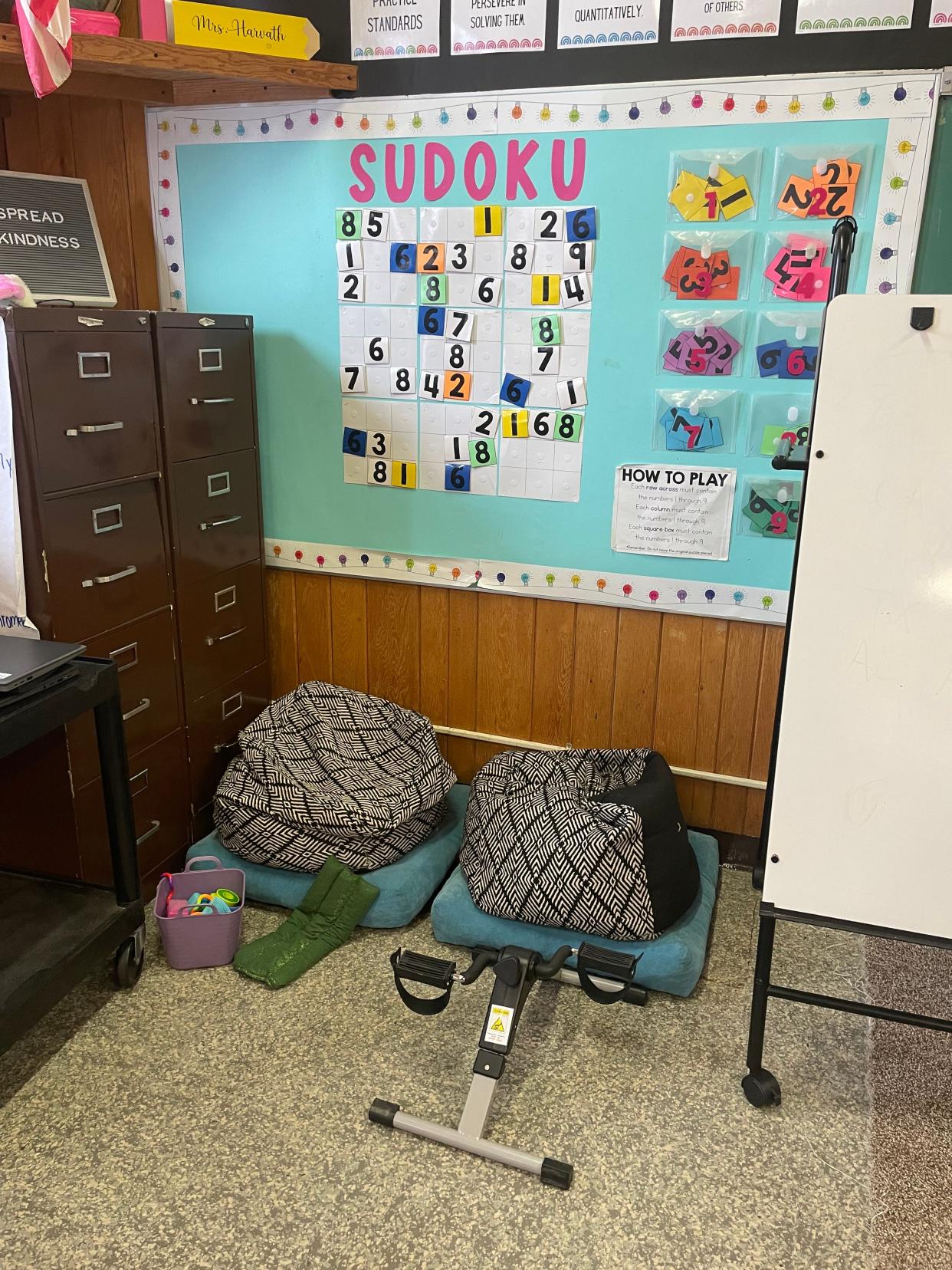

Regulation stations often go hand-in-hand with Zones of Regulation. Regulation stations — which can go by different names like "chill zones" or "calming spaces," depending on the preferences of the class — are defined spaces within the classroom where students have the freedom to go to use their coping mechanisms. Kaderabek said a well-equipped regulation station will have coping strategies that address each of the senses — things like iPods or boom boxes with calming music, decks of cards and fidget gadgets, coloring sheets, instruction cards to direct students through sequences of movements or breathing techniques, cotton balls with essential oils and even some crunchy or chewy snacks.

For some teachers, the idea of allowing kids to move to a different space during classroom instruction time is a big change, but Kaderabek said the spaces integrate well into the classroom when students are taught how to thoughtfully use them.

"There does need to be some empathy as a teacher and some ability to give up control, to believe that, as the station becomes part of their routine, they won't just go there to color or listen to music, but they'll go there when they need to and come back more regulated and ready to do their work," Kaderabek said.

'That's the first time I was listened to'

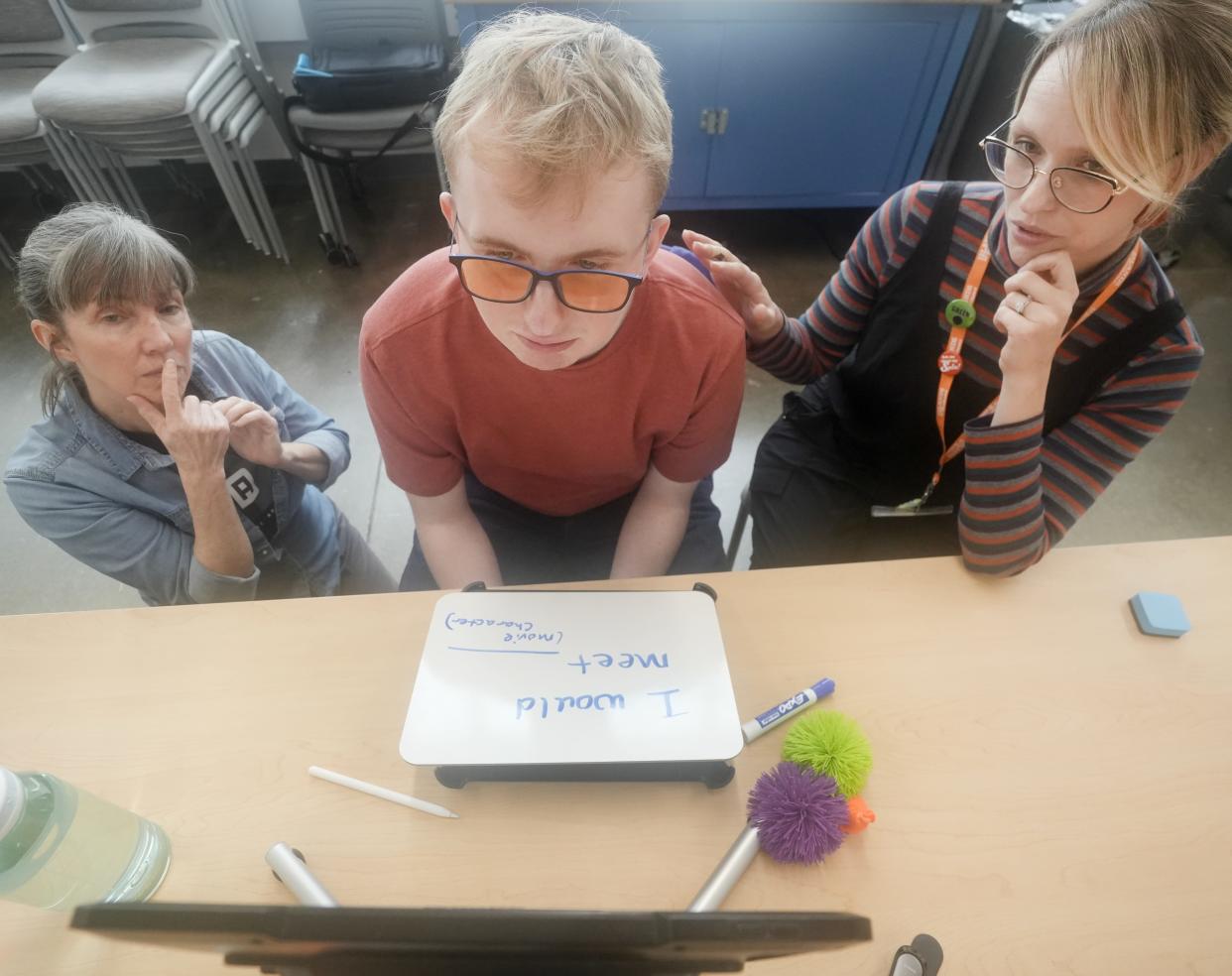

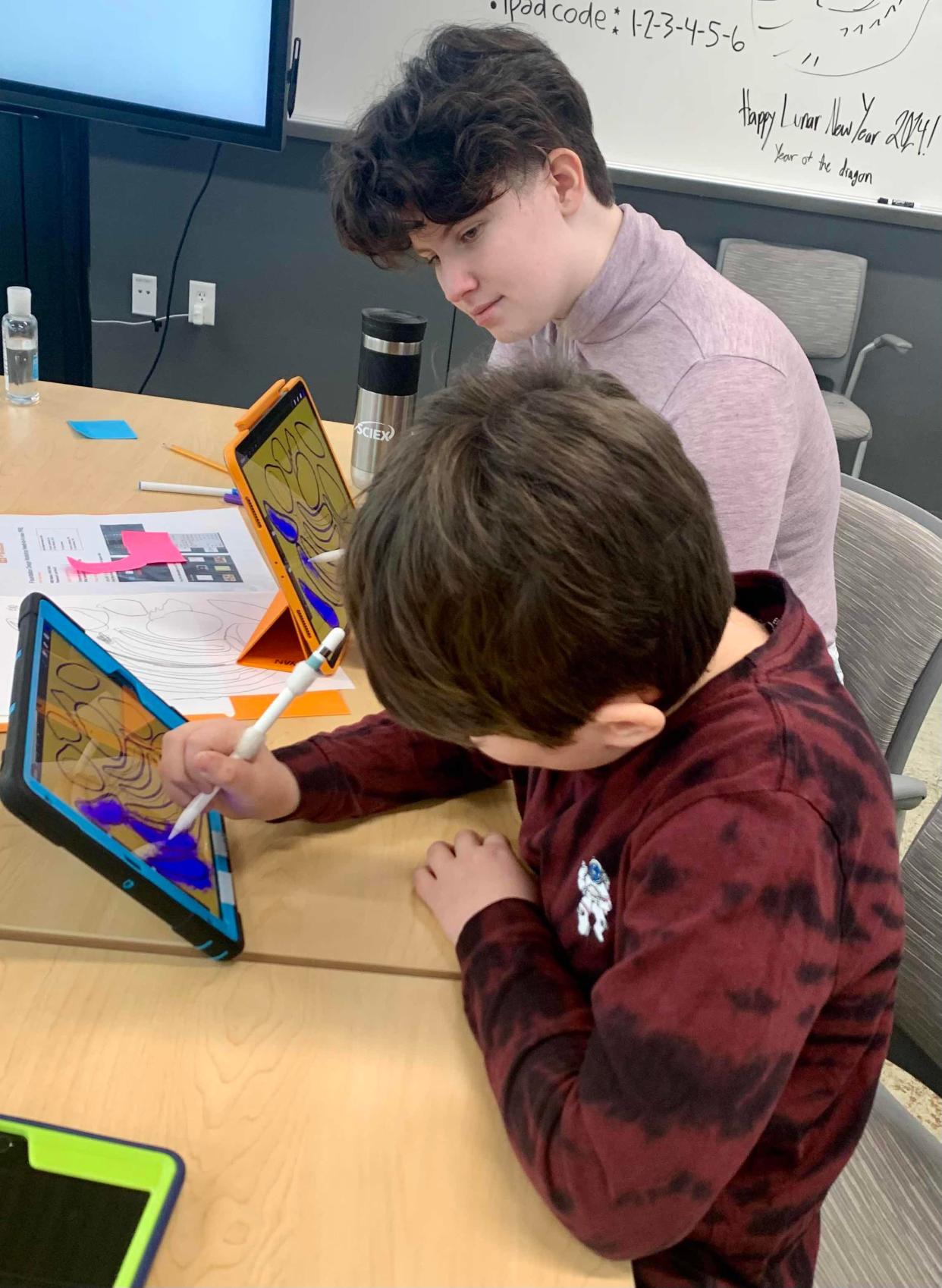

At a recent Islands of Brilliance workshop in Milwaukee, there were many strategies being employed to accommodate a group of autistic children as they worked one-on-one with mentors using technology to create artistic presentations of their special interests.

One student struggled to transition from his more laidback Saturday into working on a project. His mom stayed in the room until he, his mentor and workshop facilitator Kate Siekman worked out a plan that involved moving to a different room where the child had fewer overwhelming distractions and more freedom to move around. Later, his friend — who also found focus to be a challenge — joined him, and the two boys asked each other questions about their projects, walked around the room when they felt a need to move and took a few snack breaks. Their mentors allowed them to take the lead, and the boys always came back to working on their projects — which they enthusiastically presented to their classmates at the end of the session.

Another student at the Islands of Brilliance workshop chose one idea to work on with his mentor, then started talking excitedly about Bluey the animated dog; his mentor agreeably pulled up a reference picture of Bluey so they could change the project to the child's special interest. He enjoyed working on his project, but by the end of the session, the child was feeling dysregulated and ready to go home to watch a "Bluey" episode.

He agreed to stay for the project presentation and answered a few questions when it was his turn to show off his work. But, when Siekman asked the child how he wanted everybody to celebrate his work — typically, students ask their peers to applaud, give a thumbs-up or sometimes even dance — he said he didn't want any celebration.

And the group respected that.

For a neurotypical adult, it can be difficult to hold back from applauding a student when they've finished presenting something they're proud of. But the impulse to applaud — just like reacting to "bad choices" with punishment instead of hearing the communication behind the behavior — is more about what feels right to the adult than it is about how a neurodivergent child experiences the situation.

Margaret Fairbanks, the co-founder of Islands of Brilliance, remembers a similar situation when a teenage student participated in a workshop.

"We invited them to celebrate their work at the end of the session like we always do, but they said they didn't want everyone celebrating, so we said OK," Fairbanks said.

"And on the way home, the student told their mom, 'that's the first time I was listened to.'"

Contact Amy Schwabe at amy.schwabe@jrn.com.

What it means to be neurodivergent

According to a Cambridge University study, neurodivergent people are those whose neurocognitive functions — like learning, attention span and regulating emotions — fall outside "prevalent social norms."

While diagnoses considered to be neurodivergent continually evolve, these are some current diagnoses, as listed in "The Neurodiverse Classroom" by Victoria Honeybourne:

Autism: To receive a diagnosis, people will generally be characterized as having "persistent difficulties with social interaction and communication, and restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviors, activities and interests."

ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder): People with ADHD generally have brain differences that affect their executive functioning abilities — things like organization, memory, motivation to perform tasks and emotional regulation.

Developmental Language Disorder: People can have difficulties understanding language, expressing themselves using language, or knowing the accepted ways to use language in social situations.

Dyslexia: People with dyslexia have a brain difference that affects their ability to read and spell accurately and fluently.

Dysgraphia: People with dysgraphia have challenges with writing as quickly or fluently as other people.

Dyscalculia: People with dyscalculia have a brain difference that affects their abilities with numbers and math.

Dyspraxia, also known as Developmental Coordination Disorder: People with dyspraxia often have difficulties with coordination, movement and balance.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Wisconsin schools learn to accommodate neurodivergent students