Native American K-pop Fans Spread the Love

Although the author recognizes the nuanced differences between “Indigenous” and “Native,” they are used in this article interchangeably, with preference to being tribal-specific when possible.

More from Spin:

Korean Pop has taken Kiera Fox, Three Affiliated Tribes, places she’d never imagined. A longtime on-and-off listener since middle school, she won a lottery with upgraded tickets that included a meet-and-greet with BTS during the 2015 Red Bullet Tour. “I’ve never been star struck in my entire life. Like…I’ve met Adam Beach, you know? I’ve met Martin Sensmeier! I’ve met Wes Studi!” she excitedly recounts, comparing the seven-member superstar group to three of North America’s most renowned Indigenous actors.

Over the past 15 years, Korean Pop artists and groups have found their way into the hearts and homes of Indigenous youth all over North America—from the dormitories of the few residential schools still in operation, to tribal college libraries and flea markets, and well into the urban Indigenous milieu. Indigenous K-pop fan communities have joined forces on Twitter and Instagram, sharing artwork, beadwork, memes, and fandom-themed traditional attire. And they also represent their communities online, continually educating the public on matters of cultural appropriation versus appreciation.

As a young Diné girl growing up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a city bordering several tribal nations, I began listening to K-pop in 2010. Enamored by the honey-inflected voice of Kyuhyun from Super Junior and the lucent poetry of Tablo from Epik High, I soon discovered I was not alone. Having witnessed the increasing presence of Korean popular artistry in Indigenous spaces, I had to wonder—why?

Kat Warren, Diné, spent her middle school years growing up in California listening to a palette of late second-generation groups like SHINee and U-Kiss and thought she had outgrown it—until BTS’ ”IDOL” music video dropped. “They incorporated a lot of their traditional regalia, like hanboks. They did a traditional version of ‘IDOL’ too. That is something I think resonates with me, specifically—the idea of being traditional in a Western space.” She references the moment the boys don traditional Korean attire, singing, “You can’t stop me lovin’ myself.”

Today, approximately 71 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives live in urban locales. Warren’s mother moved their family away from the Navajo Reservation to the city when she was a young child. She acknowledges the struggles that many urban Indigenous peoples face and BTS has helped her manage: “We have to live in these cities…go to work, go to school. So, I guess we resonate with each other—trying to be traditional but also trying to navigate that space.”

Kiera Fox reiterates that BTS holds so much pride in their heritage—and it mirrors hers as well. A direct descendant of the renowned Cheyenne chief Black Kettle, she wistfully comments on BTS’ dedication to singing in Korean: “You know, that’s such a privilege for Native people…it’s awesome to see them do their music in their native language and not have to feel like they gotta conform to [doing] English music.”

For Fox, Korean acts singing in Korean are inspiring her to continue learning her native languages of Hidatsa and Cheyenne. “I can’t translate Korean. I can’t speak it. But I have this lifetime experience of being spoken to in a language that I don’t understand.”

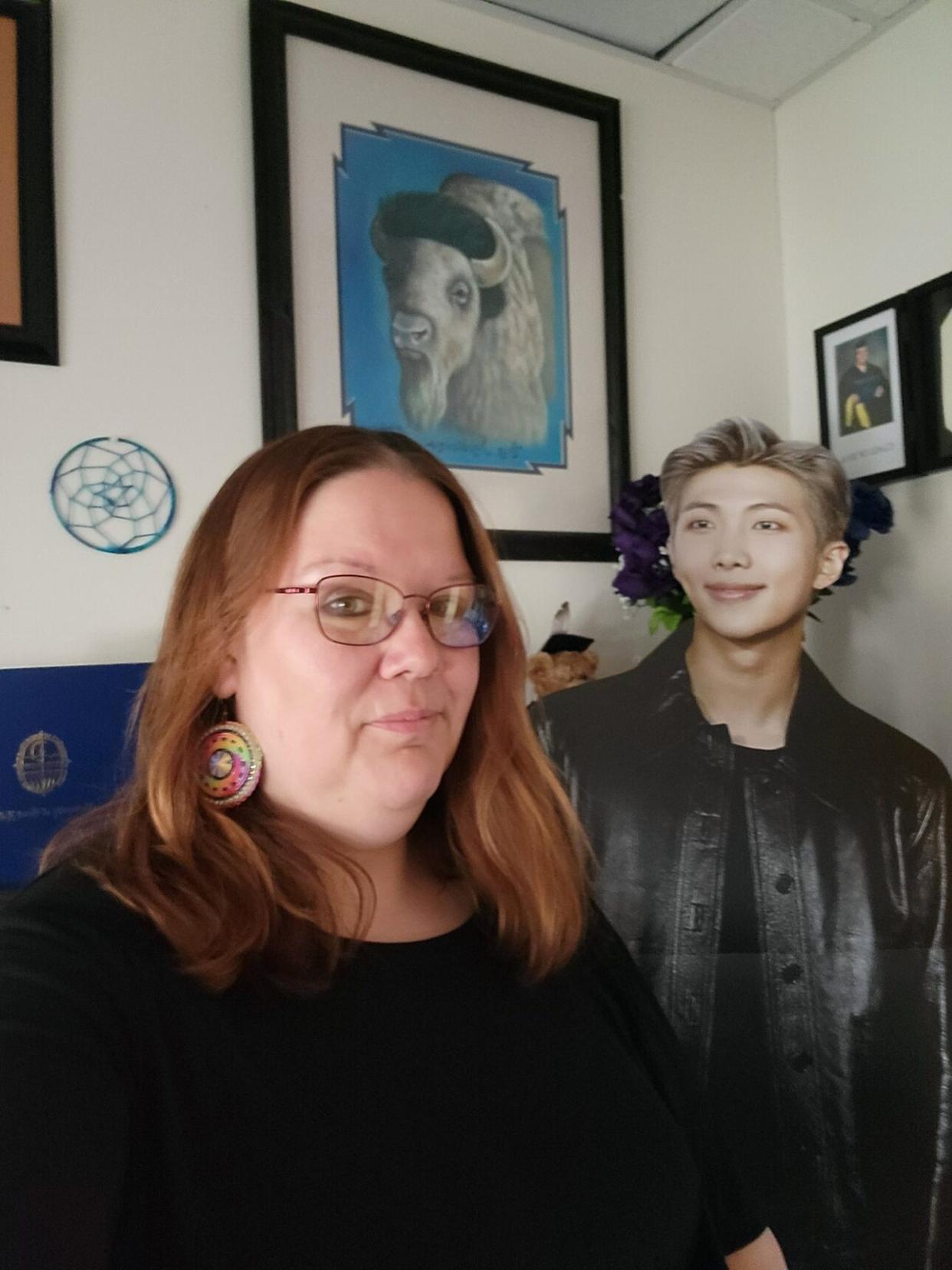

Joy Bridwell (Chippewa Cree) is a tribal college librarian in Montana whose K-pop journey began while she was pursuing her Master’s degree in Library Science. Descended from a long line of poets, she always struggled to express herself. RM’s music, however, freed her to write about her experiences as a Native woman. It is the lyrics that brought her into the K-pop fold—although she doesn’t understand Korean, she seeks out translations and internalizes their words. She gestures to a life-size cutout of RM, the BTS member with a well-documented love of literature, in her office, noting that her students will pose him around the library as a champion for Indigenous literature.

Bridwell also touches on how Indigenous kinship building practices and fandom spaces lend themselves to each other very well. She jokes, “It’s hard to find K-pop fans in Montana that I’m not related to. Like, all of my Native students who work in the library are K-pop fans.” Bridwell says she lives on a reservation, and for other reservation-based Native students unsure about attending college, Bridwell’s office has become both a musical safe haven and a place for students to feel at home away from home.

Bekah Hillis, Diné, is a professional classical violinist whose ears gravitate to the melodies and rhythms of Korean pop. Hillis grew up with strong ties to her community, and most of her friends are also Navajo K-pop listeners. She discusses how Native K-pop fandoms have made their own niche within larger fandoms, by interacting with groups like BTS or Seventeen in an Indigenous cultural context. Musically, she brings up the popular traditional Navajo love song “K-Pop Dream Boy” sung by the Martin Sisters (Diné/Dakota), which often plays on the Navajo Nation’s premier radio station, KTNN 660 AM, as an example. In the song, the sister duo sing a capella with a hand drum, “K-pop dream boy overseas / Come to my rez, marry me.”

Hillis reiterates, “we’re not being delusional!” and cites Suga’s 2022 visit to the Grand Canyon following the conclusion of BTS’ four-concert series, Permission to Dance Las Vegas. Beyond BTS, their superstar predecessors TVXQ once shot an entire photobook, A Week Holiday (2008), on Hualapai tribal lands.

Indigenous-made jewelry seems to be one of very few direct connection points between fans and idols. Beadwork is essential to Native K-pop communities and can visually signal one’s fan status. Enter the most iconic beader of them all: Stevi Riley. Riley (Anishinaabe) is not a K-pop fan herself but a “friendly supporter of the craze.” She’s spent nearly 100 hours recreating the faces of Jimin, J-Hope, Suga, V, and RM using tiny beads. Riley posted the beaded medallions, worn like necklaces, to her Instagram page, where it has become a hub for Native K-pop fans to find each other.

The girls also lament over the fake Native jewelry often worn with cowboy/hippie-themed concepts but equally praise the work of Diné silversmith Cody Sanderson, whose work has been worn by BTS’ Suga, BLACKPINK’s Lisa, ATEEZ’s Jongho, and more. Many express hope for future conversations and collaborations. Victoria Meza, Diné/Assiniboine Sioux, is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in social work, and her education has informally shaped her understanding of the ways music transcends borders. She shares, “I want to continue to believe in their goodness, but that also does come with acknowledging the most vulnerable. I feel like K-pop is really popular with marginalized groups, and I think it’s impossible to ignore that or dismiss that.”

In the meantime, Korean Pop continues to encourage Indigenous fans to be proud of their cultures, to learn their native languages—and it will continue to gather Indigenous people together, whether it be watching music videos in the dormitory commons area of a residential school, swapping handmade merch, traveling to concerts together, or just strengthening familial and friendship bonds through conversations and karaoke.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.