Nasty names, shame and disgrace: How Tennessee upset of Vanderbilt in 1916 sparked fiery sportswriter fight

Tennessee football fans stole blankets from Vanderbilt fans and spit on their parked cars, cursed the Commodores and jeered an injured player as he was carried off the field.

Those were among the fiery accusations made by Nashville sportswriter James G. Stahlman, who wrote Tennessee was a “shame and disgrace to the entire South” after the Vols beat Vanderbilt in 1916.

Knoxville sportswriter Henry E. Dougherty fired back. He wrote that Vanderbilt was a sore loser, Stahlman was a whiny apologist and Commodore fans were condescending.

“You called us some nasty names, and you poked fun at us” as if “Vanderbilt was coming over to Knoxville to show the poor deluded East Tennesseans how football should be played,” Dougherty wrote.

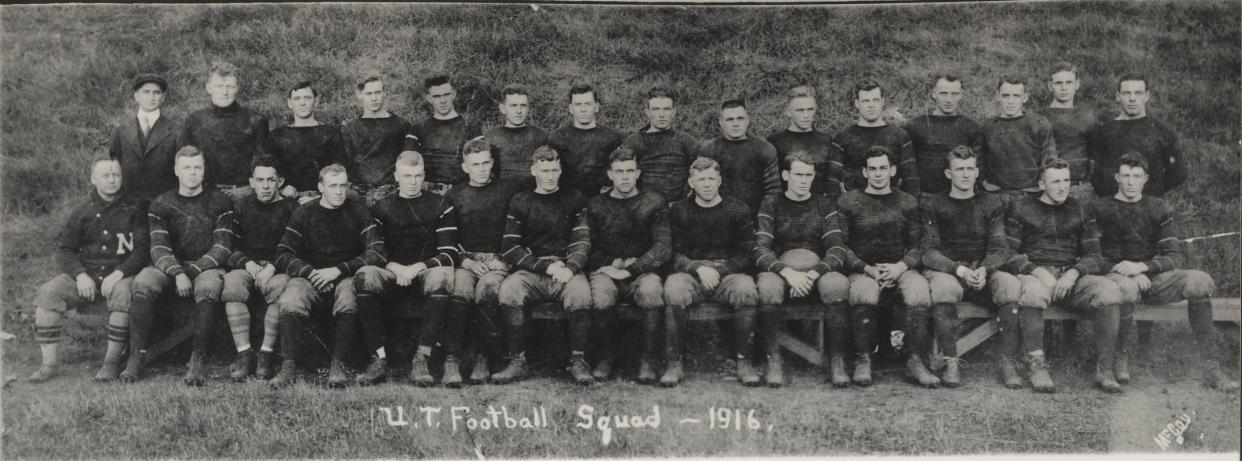

On Nov. 11, 1916, Tennessee beat Vanderbilt 10-6 in Knoxville. The game drew headlines because the Commodores, a national power at the time, suffered a surprising upset.

But that paled in comparison to the fireworks that followed.

UT fans were accused of egregious behavior, which they vehemently denied. Sportsmanship etiquette was put on trial as a football rivalry heated up. And sportswriters lobbed insults at one another across the Cumberland Plateau.

It was a weeklong war of words between newspapers in Nashville, Knoxville and every corner of Tennessee.

Vanderbilt (2-9, 0-7 SEC) plays at No. 23 Tennessee (7-4, 3-4) on Saturday (3:30 p.m. ET, SEC Network) in their rivalry that began in 1892. Here’s a colorful chapter from that 1916 game.

UT fans make ‘the night hideous for Vanderbilt’

The war of words was mostly fought between the Nashville Banner and the Knoxville News Sentinel.

But Blinkey Horn, a veteran sportswriter for The Tennessean, best summed up the shock of Vanderbilt’s loss and the celebration the losing players endured in Knoxville.

“This is not a typographical error. It is the wretched truth,” Horn wrote about Vanderbilt’s loss. “In stunned woe, the Commodore that was once king lies sprawling with another on his throne.

“In the streets, the din of frenzied Tennessee supporters, joyously maddened makes the night hideous for Vanderbilt. … The mocking chants of Tennessee are everywhere.”

Vanderbilt took the loss hard. It was a football powerhouse and the defending champion in Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, a grandfather to the current Southeastern Conference.

UT was trying to gain its footing as a consistent winner. This was only its second win in 15 games against Vanderbilt and its first victory in Knoxville.

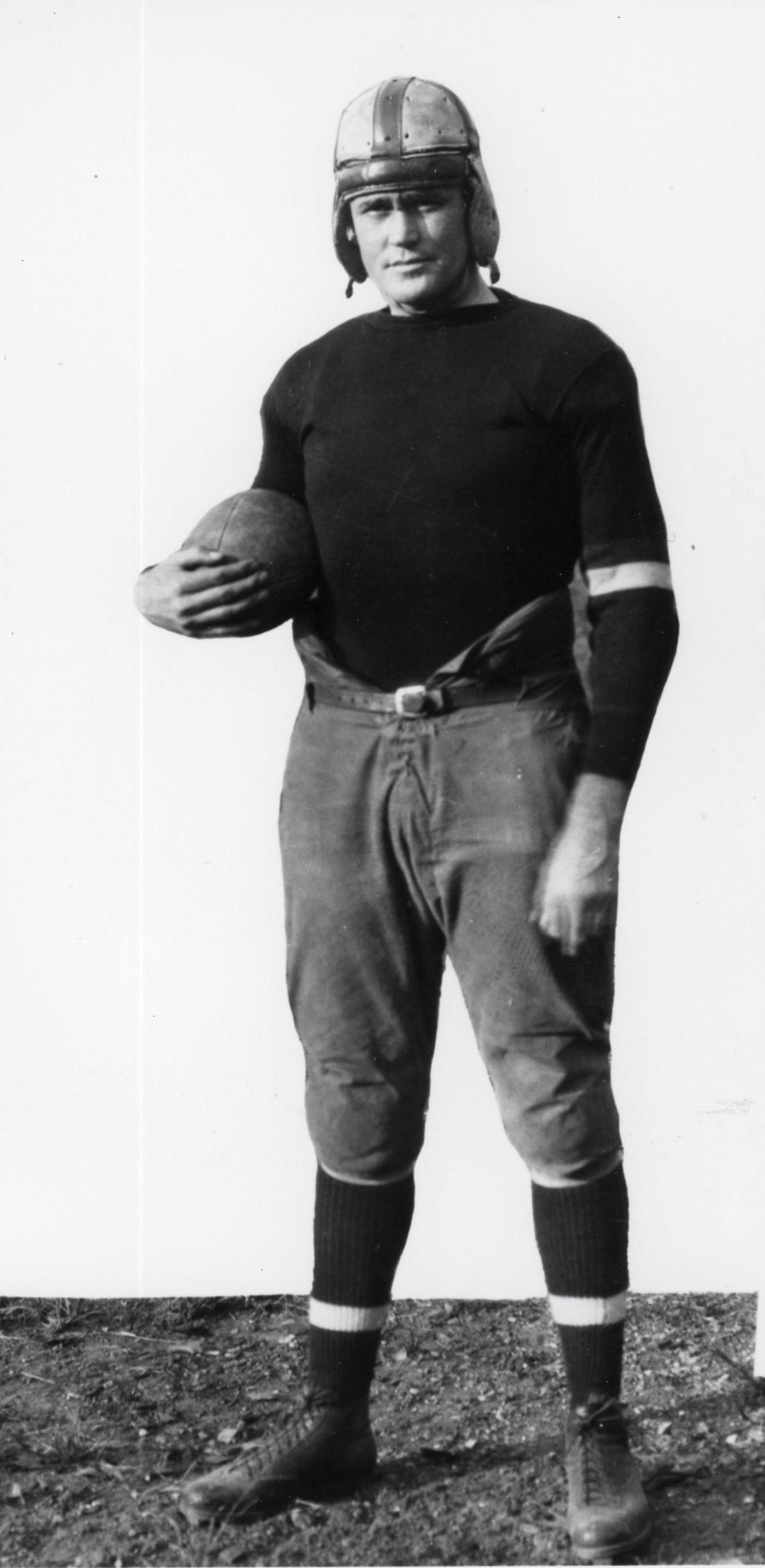

UT captain Graham Vowell scored the go-ahead touchdown on a 5-yard run in the third quarter. And the Vols defense, which allowed only 19 points that season, protected the lead to the final whistle.

It set off a celebration at Wait Field, where the Vols played their home games. Horn described the Commodores’ sorrow. But he didn’t criticize UT fans for enjoying a rare win. That came a day later in the sports page on the Nashville Banner.

VOLS VS DORES BEFORE TV 10 crazy plays in Tennessee rivalry with Vanderbilt you've never seen

‘Derisive yelping and hooting’

In 1916, Stahlman was a recent Vanderbilt graduate, a budding sportswriter and heir to the Nashville Banner, which his grandfather owned at the time.

Reporting from the game in Knoxville, Stahlman painted a picture that no other journalist did.

“Wild efforts were made to jerk the Vanderbilt blankets from around the Commodores and trample them in the dust,” Stahlman wrote. “Vile epithets were hurled and instead of decent celebration, the roosters resorted to worse tactics than rubbing it in by jeering and hooting derisively as the (Vanderbilt) team passed by.

“Some even went so far as to curse at the Vandy players and endeavored to display their disgust at Vanderbilt and all related thereto by spitting at the automobiles. The derisive yelping and hooting were bad enough, but Tennessee drew the line at nothing.”

Psychology professor countered for UT

A day later, UT denied the charges with a lengthy statement published in the News Sentinel.

“I do not think such remarks should be dignified by any notice on our part,” wrote E.P. Frost, chairman of the UT athletic council. “But if there was any unsportsmanlike conduct towards the members of the Vanderbilt eleven by the Tennessee students, I know nothing of it.

“… I cannot bring myself to believe that the Tennessee students are guilty, as charged.”

Frost, a UT psychology professor, then went a step further. He explained that it didn’t make sense for sports fans to revel in their opponent’s loss when they could simply celebrate their own win.

Today’s SEC fans might disagree.

“It isn’t good psychology to believe the students would run after a defeated team to treat it in the manner referred to by the Nashville Banner,” Frost wrote. “It is easier to believe that the Tennessee students followed their own victorious eleven off the field.”

Hollywood writer spoke for Vols

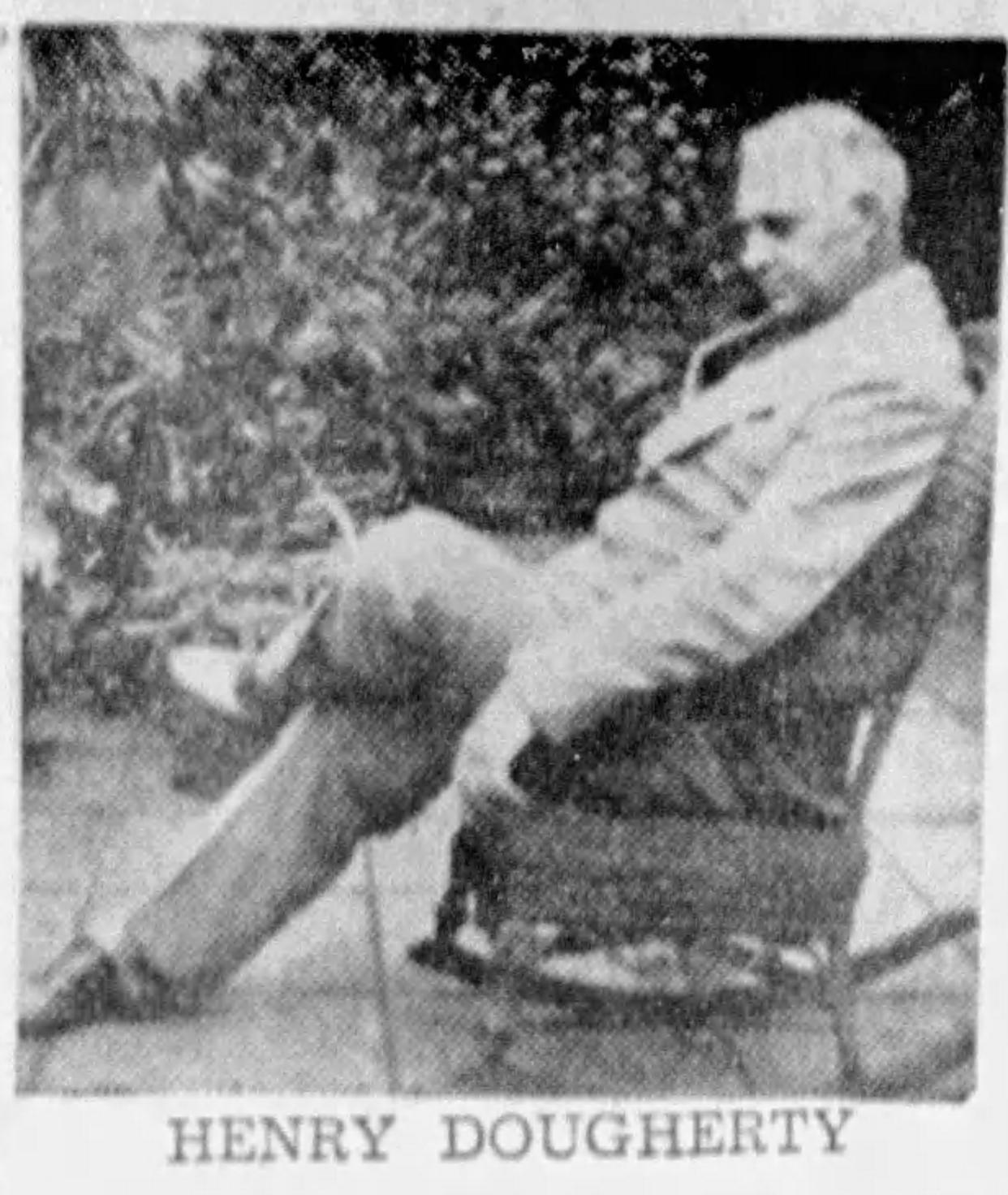

In 1916, Dougherty was finishing his tenure as News Sentinel sports editor and theater critic. His primary job was covering UT, where his brother Nathan had been a star football player and was an engineering professor at that time.

But Henry Dougherty also managed a motion picture theater in Knoxville. A few months after the Vanderbilt game, he moved to Los Angeles to work as a publicist for studios of silent films.

Years later, Dougherty would send telegrams to UT coaches before the Vanderbilt games, promising them that movie stars he worked with were rooting for the Vols.

In 1916, after reading Stahlman’s account of the postgame celebration, Dougherty fired off a 3,000-word column that had more hyperbole than a Hollywood script.

Dougherty compared UT’s win over Vanderbilt to Columbus discovering America in 1492 and the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

“That said declaration did not create such a furor and as much commotion in Philadelphia as Tennessee’s 10 to 6 victory over Vanderbilt did in Knoxville Saturday night,” Dougherty wrote.

He spent the rest of the article defending UT’s dominance in the game, refuting the claims of fan misbehavior and taunting Stahlman with language that belonged to that era.

“We have ordered ten yards of somber-hued crepe for Jimmy Stahlman, of the Nashville Banner, and we intend to tie it in appropriate folds with six orange and white ribbons – 10 to 6, you know! What about it, Jimmy?” Dougherty wrote.

Was Rabbit cheered or jeered?

The argument wasn’t just over UT’s celebration after the win. It was about the conduct of UT players and fans during the game, particularly when Vanderbilt’s star player was badly injured.

It’s what Stahlman called “the most disgusting affair, a demonstration on the field the like of which Vanderbilt had never before seen.”

Vanderbilt’s lone touchdown was scored on a 70-yard run by All-America quarterback Irby “Rabbit” Curry. But he was mostly contained by UT, led by defensive end Lloyd Wolfe. The UT yearbook playfully dubbed it the game when “Wolfe caught a Rabbit.”

In the fourth quarter, Curry, a speedy but undersized 135-pounder, was blasted relentlessly by UT defenders as the Commodores tried for a late rally. Finally, Curry was knocked out by a ferocious hit and “laid low and looked as if he were dead,” Stahlman reported.

What happened next sparked the debate that turned into a wildfire after the game.

Stahlman claimed that while Curry lay motionless, a UT player slapped the back of the Vols teammate that tackled Curry and shook the hand of another teammate that kneed him after he was tackled.

Stahlman said the Vols were settling an old score. In 1915, there was supposedly a bet among UT players about who could knock Curry out of the game. Instead, Curry embarrassed the Vols with spectacular runs en route to a 35-0 win during Vanderbilt’s famed “point-a-minute” season.

“They had planned to get the kid, and when they did the lucky guy was congratulated for his bravery,” Stahlman wrote.

When Curry was carried off the field, a crowd of about 8,000 reacted loudly. Stahlman said fans jeered Curry, celebrating that Vanderbilt’s best player was out of the game. UT fans said they applauded Curry out of respect, like they would any injured player.

After Stahlman’s accusations reached Knoxville, Mr. and Mrs. W.S. McNabb penned a letter to the Nashville Banner editor.

The McNabbs were UT fans and a well-known couple in Knoxville. He was a successful businessman, and she was a socialite who hosted events for the popular Stitch Witch Club, Knoxville's chapter of the Home Needleworkers Association.

“I feel you are doing yourself and your city more harm than good,” the McNabbs wrote to Stahlman. “I believe you have been badly misinformed.

“When Mr. Curry was down, they cheered him, not jeered him. And when he was carried from the field he remarked that our ends were ‘d--- (expletive) bad men.’ I suppose then, Mr. Curry cussed the Tennessee men, eh?”

Let the story die? Not a chance

Three days after the game, the News Sentinel said it was time to move on.

“The charges (of UT fan misbehavior) are baseless and should be refuted by merely ignoring them,” a staff editorial said.

But the News Sentinel didn’t heed its own advice, and neither did the Nashville Banner. After all, it was a juicy story. So they bled the inkwell dry and filled their pages with follow-up coverage.

“If reports from Knoxville are true, the Commodores were the recipients of the dirtiest deal they have ever had from any city since they have been playing football,” Nashville Banner sportswriter Bob Pigue reported.

The News Sentinel called out “hostile critics” like iconic sportswriter Fuzzy Woodruff and Georgia Tech coach John Heisman – yes, that Heisman – for publicly doubting UT's chances of beating Vanderbilt.

The Nashville Banner and the News Sentinel started republishing each other’s pregame coverage and ridiculing its inaccuracy.

Dougherty had predicted a close win by Vanderbilt. He was wrong. Stahlman had predicted a blowout win for Vanderbilt. He was really wrong.

“It would seem that the Banner, after making many predictions prior to the game, which were all shattered in Tennessee’s unexpected victory, was simply so badly flabbergasted that it promulgated (the narrative of fan misbehavior) in a fit of disappointment,” Dougherty wrote. “One cannot conceive of any other reason.”

Newspapers take sides in fight

Despite different accounts of the game, UT and Vanderbilt had made peace.

Vanderbilt coach Dan McGugin sent a letter to UT coach John Bender congratulating his team on the victory. And Dr. C.S. Brown, president of Vanderbilt athletic association, had thanked UT officials for their hospitality and the team’s treatment at the game.

Both teams had big conference games the next Saturday, so they moved on. But that didn’t stop the story.Newspapers from across Tennessee started taking sides.

The Knoxville Journal & Tribune, of course, backed the Vols against the attacks from the big city.

“Mr. Stahlman, of the Nashville Banner, may be a star when it comes to disporting himself in the luxurious and fragrantly perfumed confines of the upper strata,” The Journal wrote. “But as a loser, he is a bitter, distinct and misleading failure.”

The Nashville Banner reported that Vanderbilt was the superior team and that UT’s win was a fluke. Stahlman said McGugin’s decision to take a Saturday morning train to Knoxville rather than Friday afternoon left the Commodores too tired to play.

The Tennessean countered with a column by Horn, who praised the Vols for taking advantage of an ill-prepared Vanderbilt team that underestimated them.

“Fate has a way of sternly rebuking those who jest at rival’s worth,” Horn wrote. “The best team won.”

The Memphis Commercial Appeal echoed Horn’s take, giving credit to UT for rising to the occasion and criticizing Vanderbilt for its collapse. And the News Sentinel celebrated the fact that the Associated Press, regarded as an objective news source, gave the Vols credit for outplaying the Commodores.

What happened to Stahlman and Dougherty?

So did UT fans actually curse Vanderbilt’s players after the game? Did they steal the opposing fans’ blankets and spit on their cars? Did they jeer Curry as he was carried off?

We’ll never know.

But the Chattanooga News had the most interesting report of what really happened at that 1916 Vanderbilt-Tennessee game. It suggested that some of the fan misbehavior that Stahlman reported may have actually occurred, but it didn’t make any difference in the game.

“Even if juvenile supporters of Tennessee did attempt to appropriate as spoils of war, Commodore blankets, how can this have affected Vandy’s play?” the Chattanooga News reported.

“Even if the Vols planned to get Rabbit Curry, as they did do and as Stahlman charges, there is no taint in poor sportsmanship attached. If an eleven can put out of commission a rival star by clean, hard tackling it is as much within the law as for a soldier to shoot down an adversary in open combat.”

That was unfortunately prophetic. In 1918, Curry, a fighter pilot, died when his plane was shot down by Germans over France in World War I.

That November, the Nashville Banner honored Curry in its coverage of Vanderbilt’s 76-0 win over the Vols – a game which UT still doesn’t recognize as official because it suspended varsity football during the war.

But Vanderbilt claimed it as a legitimate win, and Nashville newspapers said it was revenge for the 1916 game. But Stahlman wasn’t there to fight that battle. He had left his typewriter to join the Army infantry in World War I.

In World War II, Stahlman left the Nashville Banner again to serve in the Navy as a commander and public relations director.

It’s possible he and Dougherty worked in the same vicinity. Stahlman sometimes managed Navy news in the Pacific. And Dougherty, then the editor of the Honolulu Advertiser, was on site for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Stahlman was the Nashville Banner publisher for decades. He served on the Vanderbilt Board of Trust for almost 50 years, donating his time and millions of dollars to his alma mater.

Meanwhile, UT dominated the football series for the next century, but the Commodores stole a few victories along the way.

Stahlman died on May 1, 1976, after suffering a stroke during a Vanderbilt board meeting. The last Vanderbilt game he saw was a 17-14 win over UT, and it was played in Knoxville.

Adam Sparks is the Tennessee football beat reporter. Email adam.sparks@knoxnews.com. Twitter @AdamSparks. Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

Get the latest news and insight on SEC football by subscribing to the SEC Unfiltered newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Tennessee football win vs Vanderbilt in 1916 sparked sportswriter fight