The Murphys want to protect their progressive NJ legacy — fueled by the line | Stile

Last week, the two leaders in The House of Murphy offered a unified, macro-defense of New Jersey's county line system, which gave us a two-term governor from Goldman Sachs.

It is best summarized this way: Despite all the complaints from grassroots activists and progressives about the line balloting that gives endorsed candidates an unfair advantage in primaries, it still produced progressive leaders in New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy argued.

“I frankly think the line has served us pretty well," he told reporters last week. “Progressives who are out there trying to look at whether or not they got a good government ... I'd like them to find a more progressive government in America than what they got the past 6½ years, with yours truly elected twice.”

New Jersey first lady Tammy Murphy, whose four-month campaign for the U.S. Senate went down in flames amid a grassroots uprising over the party line on county ballots, offered up a similar defense.

“We've elected some of the most progressive leaders of our time," she said to reporters three days after quitting the race.

A Wall Street gloss-over won't clean up the NJ county line

This kind of results-oriented reply from two figures groomed by the ethos of Wall Street is not surprising, nor is it a convincing defense of a corroded, Tammany Hall-style relic that is under siege in a federal courtroom and from grassroots anger on the U.S. Senate campaign trail.

On Friday, an injunction in the case brought by Rep. Andy Kim, Murphy’s rival in the Democratic U.S. Senate primary race she quit, appeared to doom the line’s future and set in motion redesigns of New Jersey primary ballots in 19 counties.

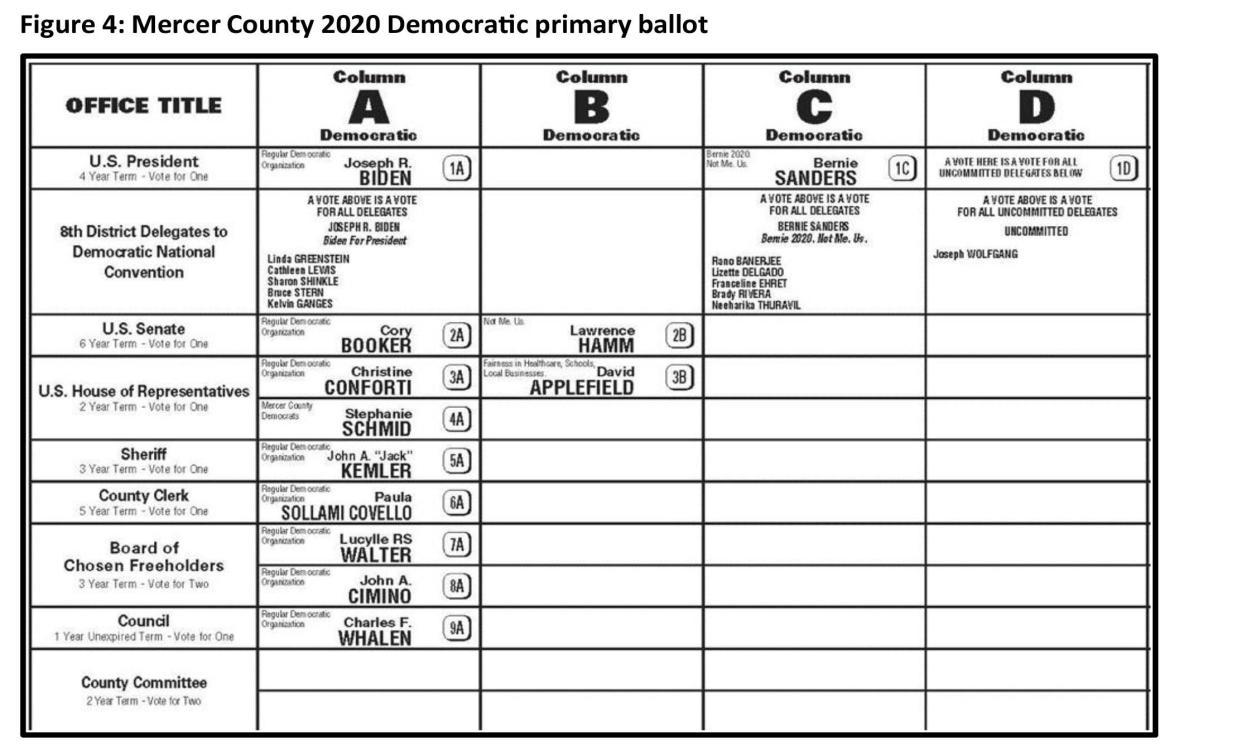

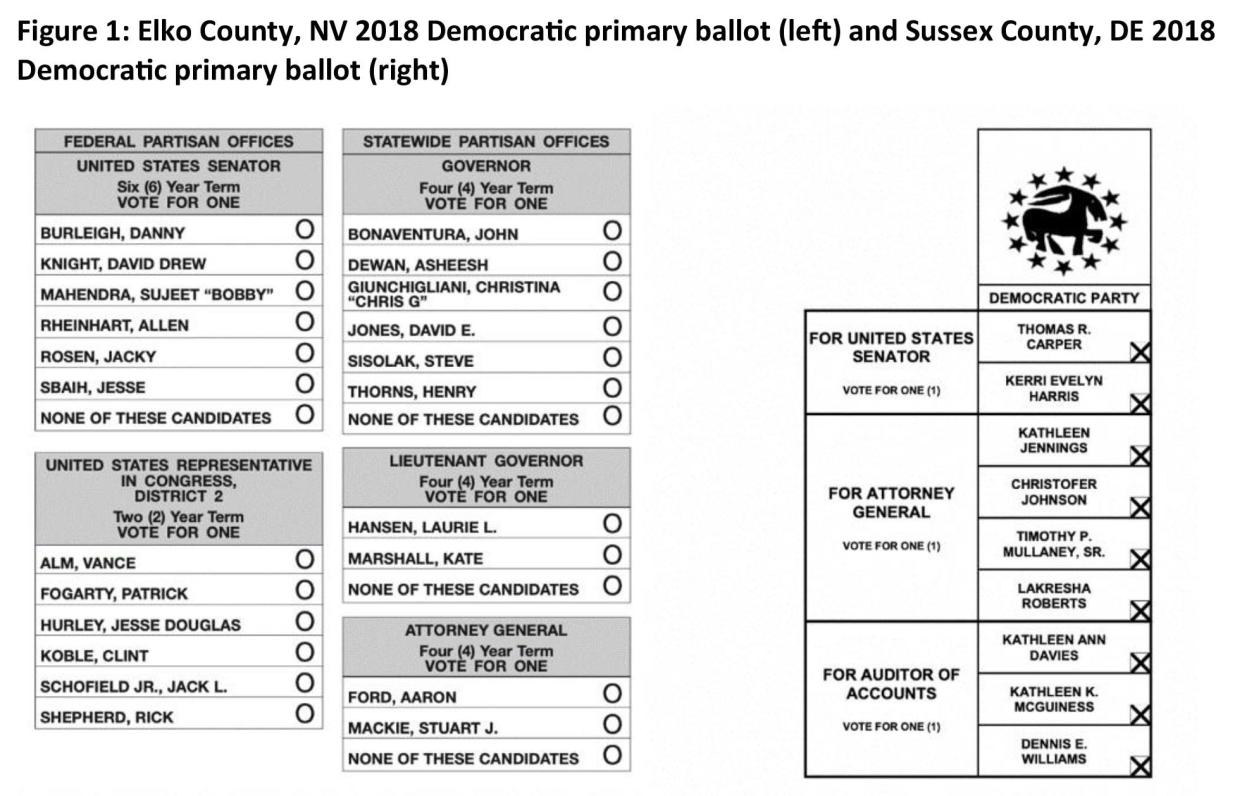

Still, the Murphys’ defense of the line glossed over the defects of a method in an anti-democratic system that confers enormous institutional advantage on the primary ballot to endorsed candidates, who are bracketed under the party slogan and in a “line” or column or row with other endorsed candidates.

Those lucky enough to get the line almost always win; off-the-line candidates are often scattered around county-level ballots with partial or no slates, in what is known as “Ballot Siberia.” Off-the-line candidates have a better chance at Mega Millions.

Granting someone that coveted prize has been an instrument of power for many county leaders, who use it to reward loyalists, punish dissidents and scare away challengers. Office seekers who are desperate to get ahead pledge their fealty to the boss. Incumbents, eager to keep their spot on the county commissioner boards or in the Legislature, often become rubber stamps who rarely buck the dictates from the home clubhouse. Activists say the whole system stifles competition, blocks reforms and fosters closed-door corruption.

The governor's comments point to what he believes is a strongly progressive résumé: raising taxes on millionaires, codifying gay marriage and abortion rights, increasing the minimum wage and enacting pay equity laws. Murphy's accomplishments did not, however, come about through promising these goals to county bosses, who in turn granted him the coveted bracketing on the ballot.

He won those invaluable ballot placements by outbidding his rivals for the nomination in 2017 and winning the line in 19 of 21 counties — an advantage, it turns out, that proved to be critical. Murphy captured only 53% of the vote that year, while his two challengers who ran under progressive slogans, former U.S. Treasury official Jim Johnson and former Assemblyman John Wisniewski, split the other 47%. The results suggest that he probably would have lost without the line.

“I think what [the line] produces is whatever the machine needs to produce to stay in power," said Julia Sass Rubin, a Rutgers professor and prominent critic of the line balloting. “In Murphy's case, because he had the resources to run and he ran as a progressive, we got a progressive governor. That that's not because of the county line system. It's just sort of happenstance.”

Sass Rubin, who found that candidates for Congress between 2002 and 2020 who were granted the line enjoyed an average 38-point advantage over those who ran off the line, added, “Machines are about power and money. They're not about ideas.”

Former Rep. Tom Malinowski, a Democrat who lost his 2022 reelection after power brokers essentially allowed the 7th District in Central and North Jersey to become more Republican after the once-a-decade redrawing of congressional boundaries, said he believes that Murphy is good governor.

“Just because good people have gotten elected under the system doesn't mean it's the best system," he said in an interview. “And the question is: Would we be better off with a system that doesn't give individual power brokers and Democratic and Republican stronghold counties the power to choose our elected officials? I think we'd be better off. I think we get better policies in the long run.”

Malinowski also said the system encourages county leaders to nurture and protect their local machine candidates at the expense of larger Democratic Party interests around the state. County machines hoard resources instead of using them to expand into more competitive, purple areas. It was that kind of parochial thinking that doomed his reelection.

“The power that the party line gives our [county] chairs incentivizes them to create more safe districts where they can use that power even at the expense of losing potential winnable congressional seats," he said.

More Charlie Stile: How far will the fallout from the end of Tammy Murphy's Senate campaign reach? | Stile

The line's outcome awaits

For years, the line proved to be an immovable feature of New Jersey politics that was used by both parties in 19 of 21 counties. New Jersey is the only state in the nation that uses the method. And that kind of narrow thinking has national implications — the gain or loss of a few seats around the country could shift the balance of power in the House.

The furor over the line format took center stage in the Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate after Tammy Murphy jumped into the race in November and quickly won the endorsements of the power brokers in the largest Democratic counties.

That meant she would win the ballot line in those counties. And, as history has shown, it also turned Murphy into the front-runner for the nomination, despite her lack of experience and her pedigree as a registered Republican and donor — as recently as 10 years ago.

Democratic Party activists fumed at what they saw was an entitled candidate coasting to the nomination on the coattails of her powerful husband — nepotism at its worst. The Murphys strongly denied the charge, but the first lady's chief rival, Kim, made the issue the centerpiece of his campaign, and in February he filed a federal lawsuit against the line system, asserting that it is unconstitutional.

Kim and two other congressional candidates, who joined as co-plaintiffs in the lawsuit, want to replace it with a block ballot — where all candidates for the same office are grouped together instead of in a line. The format is used widely around the country.

A ruling on the suit could come any day.

The tactic set off a cascade of legislators and gubernatorial candidates for governor calling for reforming the line or abolishing it altogether. And when Attorney General Matthew Platkin — a Murphy loyalist — deemed the system unconstitutional and notified the court that he would not defend it, it seemed the die was cast. A week later, Murphy dropped from the race.

For now, the Murphys' legacy will include this defiant defense of the system. Though they both say they are open to reforms, it's unlikely that any proposed changes to the law are going to well up from the Democratic-controlled Legislature, where virtually every member rose to power with the help of the line ballot.

And many of those graduates of the line system are producing bills that are clearly not in step with a progressive vision. Last year’s Elections Transparency Act opened the floodgates for larger streams of campaign cash. A dogged attempt to gut the Open Public Records Act remains very active despite a significant pushback from civic groups and grassroots activists. And, Sass Rubin notes, 14 Democrats signed on to legislation that would permit public school vouchers for private school tuitions.

“I would argue we have a population that would support a much more progressive set of ideas than we have," she said.

Charlie Stile is a veteran New Jersey political columnist. For unlimited access to his unique insights into New Jersey’s political power structure and his powerful watchdog work, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: stile@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Phil and Tammy Murphy: Progressive NJ legacy brought to you by the line