How much would it cost to finish Columbus sidewalks? You could buy an MLB team for less

Across uneven terrain, over rocks, under trees and at times through patches of mud and dirt.

It's a path that might sound fun to hikers. But without sidewalks along Cooke Road in Columbus' Clintonville neighborhood, it's one of two routes brothers Elliot and Henry Meyer can take home from their school bus stop every afternoon.

Elliot, 7, and Henry, 10, have strolled the path countless times as cars fly by just feet away on the busy two-lane road. It's a potentially dangerous trek that weighs on their parents, but one that many central Ohioans know themselves as more than half of Columbus remains without sidewalks to protect pedestrians more than 212 years after the city was founded.

As much as 60% of Columbus remains without sidewalks or curbs — the small yet critical barrier that helps safeguard pedestrians from drivers moving much faster down the road. That, coupled with federal research that shows 100 kids are killed and more than 25,000 are injured going to and from school each year, makes every walk from the bus stop more treacherous than it needs to be, said Chuck Meyer, the boys' father.

Share your story: What are sidewalks like in your Columbus neighborhood? Let The Dispatch know

"Frankly we're only doing it in the afternoon, I don't even want to think about the additional risks of doing that in the morning when it's dark out and people are going to work," Meyer said of the trek home from his children's bus stop. "It feels like a problem you would have in a rural area and not in a city that's been around as long as Columbus."

Columbus' lacks of sidewalks and curbs is a complicated problem, said Brian Ashworth, the city's transportation planning manager.

Chief among the reasons is the cost. Constructing a new sidewalk costs an estimated $400 a foot, Ashworth said, estimating all costs such as leveling and removing trees but not specifically whether using asphalt or cement. That estimated figure translates to more than $2.1 million for a mile of sidewalk.

To fill in 1,453 miles of sidewalk gaps in the city at that price tag, Columbus would need to spend more than $3 billion. It would cost less to buy a Major League Baseball team, a few yachts or a private island near the Bahamas.

"A lot of it is funding, to be honest," Ashworth said. "We don't have that much that's set aside. We only have a certain amount of annual capital improvement budget from city council specific to sidewalk funding."

On top of cost, many areas of Columbus that don't have sidewalks or curbs were annexed by the city in later years or were built before sidewalks were required, Ashworth said. Often, constructing sidewalks or multi-use pathways in already developed areas leads to right-of-way issues or the need to move utility poles.

And while adding sidewalks typically increases home values in neighborhoods, Ashworth said some residents don't want to deal with the expected upkeep.

"We're trying to kind of work backwards in a lot of areas of our community," Ashworth said. "In some places, even not far from Downtown neighborhoods, people just don't want sidewalks. They've been without them for decades and they don't want what they think might come with them."

2 miles versus 47 miles

Although resources limit new sidewalks and paths, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced a $100-million, two-mile urban pathway in February that will be built throughout Downtown, including areas that have existing sidewalks.

Named the Capital Line, it will be funded by private, public and philanthropic sources. If the $100 million was instead put toward paths in areas without them, it could fund as much as 47.3 miles of sidewalks, using the city's own cost estimates.

Peggy Williams, secretary and zoning chair for the South Linden Area Commission, told The Dispatch it's difficult for her to understand why the Capital Line is such a high priority instead of areas still in need of safe walking routes.

"You could use that $100 million to finish all the sidewalks in Linden or split it up to help take care of all the other neighborhoods," she said.

Although costly, the Capital Line could yield new business development and result in hundreds of millions in new revenue coming from places along the path, city spokeswoman Melanie Crabill told The Dispatch.

When asked about the lack of sidewalks, Crabill said the city is in the midst of taking inventory of them. The last time that was done a few years ago, 53% of Columbus had access to sidewalks, with or without curbs and not including multi-use paths.

"Pedestrian safety is a priority for all of our neighborhoods, including Downtown," Crabill said via email. "We fully believe we can support the Capital Line project while still supporting pedestrian safety projects around the city."

At least 13 projects in progress or recently completed will add miles of sidewalk in different areas of Columbus this year, and the forthcoming Linden Green Line will transform a seven-mile corridor of abandoned railway into a park and trail running from Downtown, through Linden and to Cooper Park on the North Side, according to the city.

A ballot initiative that voters could decide on this fall called LinkUS would fund more than 500 miles of new sidewalks and bus rapid transit in central Ohio. Columbus also requires private developers to construct sidewalks outside new buildings or pay money to help build sidewalks throughout the city, Ashworth said.

But gaps remain, including the ones Meyer's children and others have to trek across each day.

As of 2021, there were at least 3,150 miles of gaps throughout all of Franklin County, according to a mobility report from LinkUS. At each of those gaps where sidewalks end, pedestrian accidents are twice as likely to occur, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

Numbers like those have left Meyer questioning why work on the Capital Line, which is slated to begin in 2025, should take precedence over those gaps in sidewalks and neighborhoods without any at all.

"Let's get the core functional services of the city taken care of before we worry about that," Meyer said.

'I almost got hit yesterday'

Shelisa Nicole Williams has no choice.

As a neighborhood commissioner, she wants to serve her community. But every time she leaves her house, she's forced to put her life at risk.

Williams uses a wheelchair and travels around her neighborhood in it. But sidewalk gaps and a lack of walkways altogether force her to roll along city streets, where she said not a week goes by without her almost getting run over.

"It happens all the time. I almost got hit yesterday," Williams said referring to last Monday. "I don't let my wheelchair define me. ... I just take it day by day. But you just want people to care about what you're going through."

While Williams wants more and improved sidewalks so she can travel worry-free throughout her entire neighborhood, she said it's about more than just her own needs.

Not everyone in South Linden owns a car, Williams said, which makes sidewalks all the more necessary so people can safely get to bus stops.

Being car-focused isn't unique to Columbus, though.

Like many American cities that grew substantially after the 1950s, much of modern Columbus was built around car culture, said Jason Reece, an associate professor of city and regional planning at Ohio State University.

"It's definitely a time period thing. ... We were really building only for cars in that time period and paying limited attention to the role of sidewalks," Reece said. "That creates quite a conundrum, because then you have a lot of the city that's disconnected from pedestrian access, which means you got to go back in and retrofit those neighborhoods."

It typically takes decades for cities to shift their thinking when it comes to mobility, Reece said. But that can seem like forever for residents of Columbus neighborhoods that have only a patchwork of sidewalks or none at all, he said.

As summer approaches, Williams worries about the children in South Linden who will be out and about. She thinks about how they'll rely on the mishmash of area sidewalks to get to friends' houses or events.

"We need wider sidewalks, safer sidewalks, sidewalks with no gaps and no holes in them. Period," Williams said.

'We're forgotten about'

Trying to get a sidewalk put in has become something of a hobby for Mallory Honigford.

Honigford, who lives on Columbus' Northwest Side with her husband, Craig, and their three kids, said she has been submitting requests for a sidewalk to the city's 311 service since at least 2015.

The Honigfords live at the intersection of Constitution Place and Wilson Bridge Road, and the sidewalk stops at the end of their driveway.

So much is nearby, including the school Mallory Honigford's kids attend and Olentangy Park. But the mother of three said her family feels trapped by a busy thoroughfare with no walkway other than the road's narrow shoulder.

"We've done family bike rides and walks, but we're always trudging through grass and people's front yards," she said.

While the Honigfords have a Columbus address, Worthington is just blocks away. It's areas like these where Columbus residents feel like they live in an odd limbo between the city of Columbus and nearby suburbs, said Sharon Rastatter, chair of Columbus's Far West Side area commission.

Rastatter said she often sees people walking along roads without sidewalks in her neighborhood to get to school, stores or jobs. Some of the Far West Side is adjacent to Hilliard, which Rastatter said has left many in that area feeling like they're on their own.

"We're forgotten about ... but the sad thing is we're used to it," Rastatter said. "The city casts shade on us for living in a suburban area, but they shouldn't have annexed us if they didn't want to deal with us."

Year after year, Mallory Honigford said she received generic denial emails from the city stating there wasn't enough funding to go around for sidewalks. In the intervening years, she's written to the Ohio Department of Transportation and the city of Worthington, but hasn't had any luck.

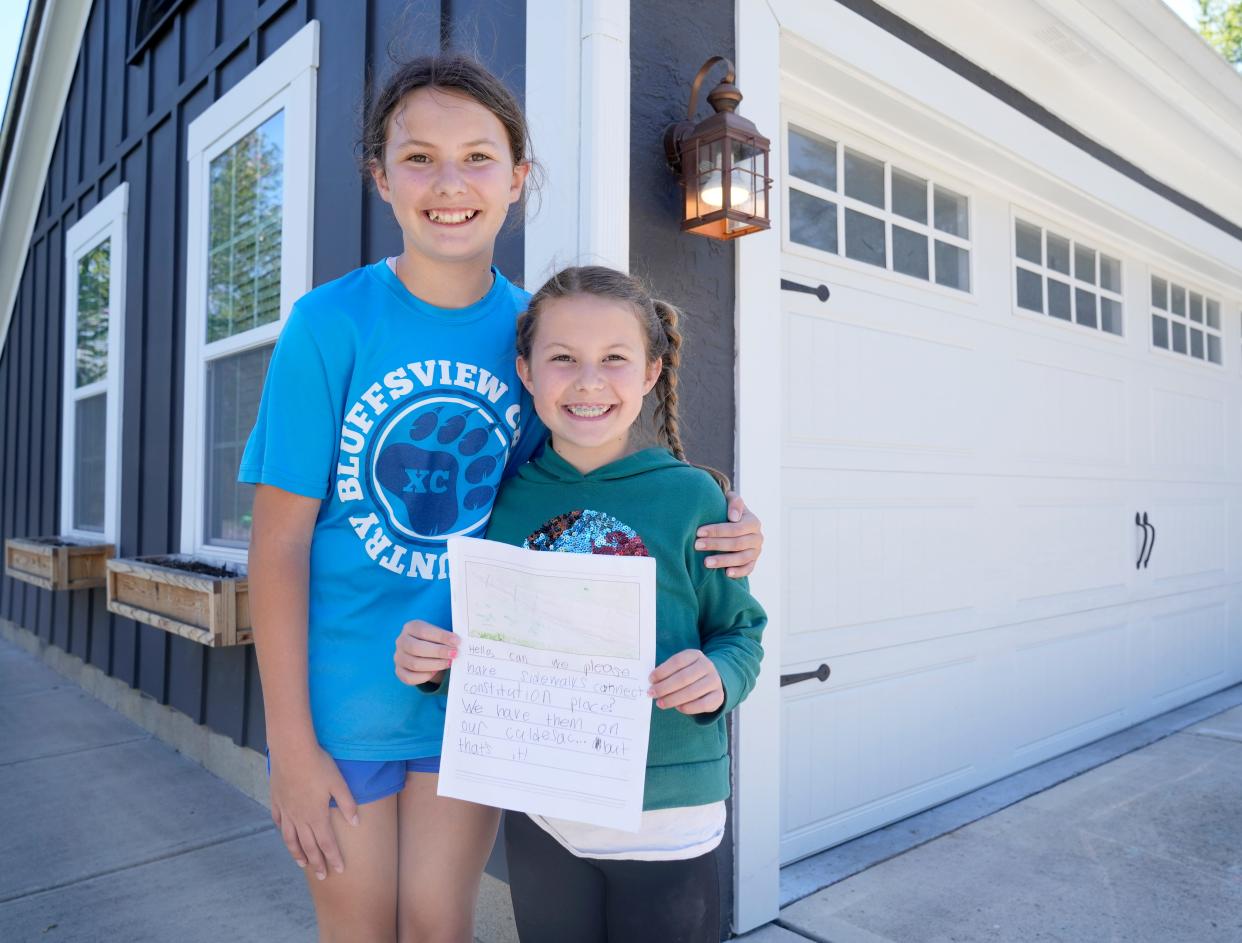

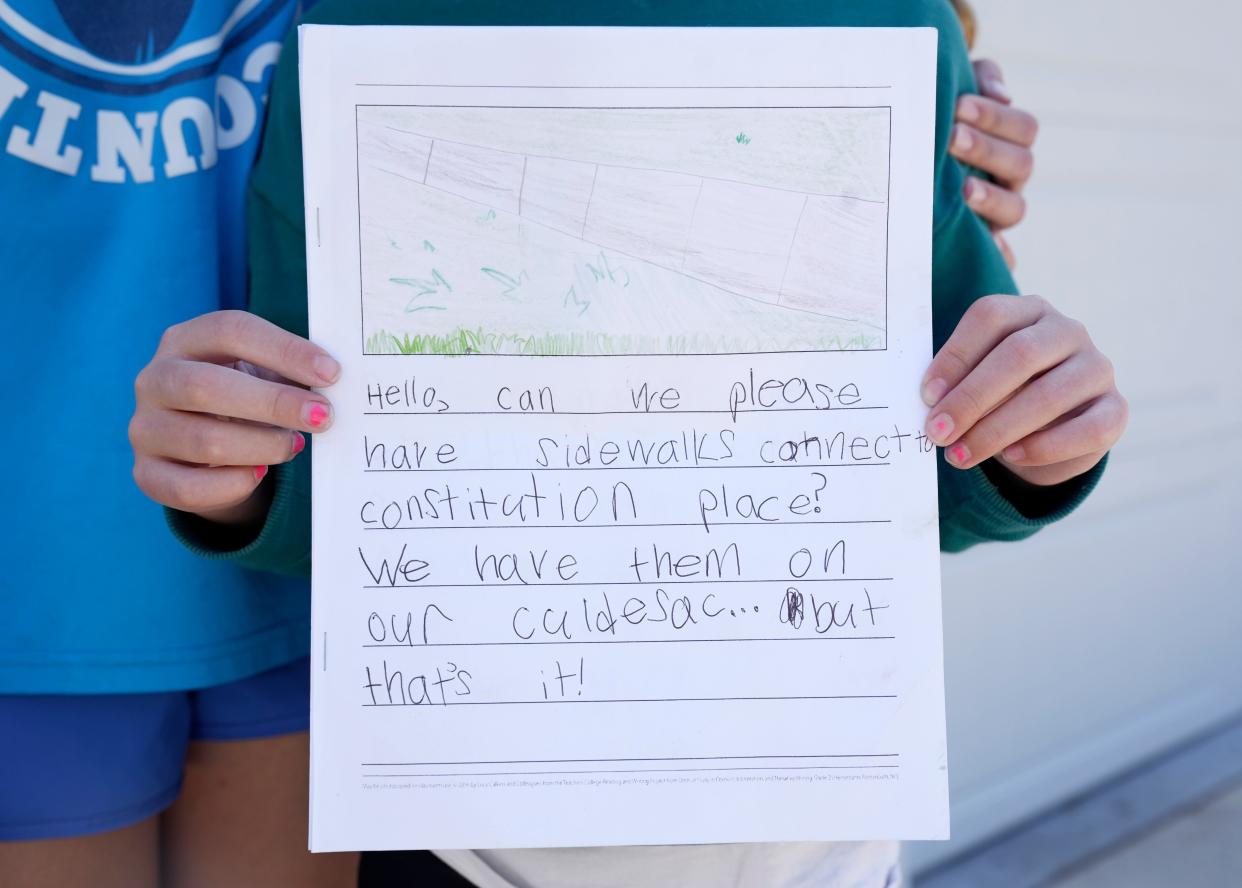

Finally, after years of being denied a sidewalk, Honigford enlisted the help of her kids in 2022.

Together, her daughters Lucy, 10, and Hazel, 8, wrote and illustrated a letter to city officials asking them to put in sidewalks beyond the street they live on. The girls expressed their frustration, with one of them writing: "It makes me sad that I can't go further with my family. Crossing a busy street and riding (a bike) into the grass is very hard."

Despite the letter, the Honigfords got the same response from Columbus: Their sidewalk request still wasn't in the city's budget.

"No one wants to claim us," Mallory Honigford said. "... I feel like I've tried everything."

@MaxFilby

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Columbus pedestrians face risky walks with 1,000+ miles of no sidewalk