Move over, Everest climbers. The rarest peaks to scale may be in Miami-Dade County

Some climbers dream of summiting Mount Everest. Others chase the tallest peaks in all 50 states. And then there are the truly rare mountaineers: those who aspire to reach the highest point in a flat-as-an-arepa county like Miami-Dade.

They’re members of the Highpointers Club, a small but enthusiastic group of hobbyists who travel the U.S. documenting their journeys to the tallest natural peak in every state and, for the truly obsessive, every county. (Landfills and other artificial peaks don’t count.) No one has ever done all the counties — or even come close. The current leader, Bob Schwab, has reached the peak of just 2,385 of America’s 3,143 counties.

Sometimes, reaching a county high point means scaling a majestic peak like Mount Rainier (the highest point in Pierce County, Washington, elevation 14,411 feet). But, for this group at least, that’s easy. Hundreds of thousands of people have done that.

A county like Miami-Dade, however, is harder.

For starters, the land is so flat that there are 28 areas at roughly 20 feet of elevation that might be the highest natural point in Miami-Dade. To say for sure that you’ve been to the peak of the county, you have to stand on top of all of them. Just driving to all 28 points through Miami traffic is a momentous feat. Then you have to sweet talk or sneak past the private property owners who own the land or, in some cases, the public officials guarding government property.

Miami’s hidden high ground: What sea rise risk means for some prime real estate

Only two people — at least, according to official county highpointer trip reports — have ever done it: Dave Covill, a 65-year-old retired oil industry engineer who lives in Evergreen, Colorado, and Michael Schwartz, an 80-year-old former Navy intelligence officer living in Mendham, New Jersey (known to friends and family as “Spooky Mike” in a nod to his former spying days). And even they aren’t sure where the county’s true high point lies.

“The verdict is still out as to exactly what area is the highest,” said Schwartz. “I don’t think that’s ever going to be totally verifiable.”

From mountain peaks to county high points

Most county highpointers start out as state highpointers, traveling the U.S. climbing formidable name-brand mountains like Denali (Alaska), Mount Whitney (California) and Mount Elbert (Colorado). They aim to reach all 50 state peaks, or else get as close to 50 as they’re going to before injuries, old age, work responsibilities, family obligations or financial constraints catch up to them.

“When you reach a certain point on your list, you either finish it or you can’t go any further because it’s beyond your means,” said Covill, who in his younger days climbed all 50 state high points, along with Aconcagua, the biggest mountain in South America, Mont Blanc, the tallest peak of the Alps, Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest point in Africa, and every major volcano in Mexico.

“So what do you do?” he said. “You find another list.”

For Covill, and hundreds of highpointers like him, that meant summiting counties instead of states. He started near his home in Colorado, where plenty of nearby counties had sizable and rewarding mountains to climb. Then he worked on expanding his “glob,” the term highpointers use to describe the collection of neighboring counties they’ve summited.

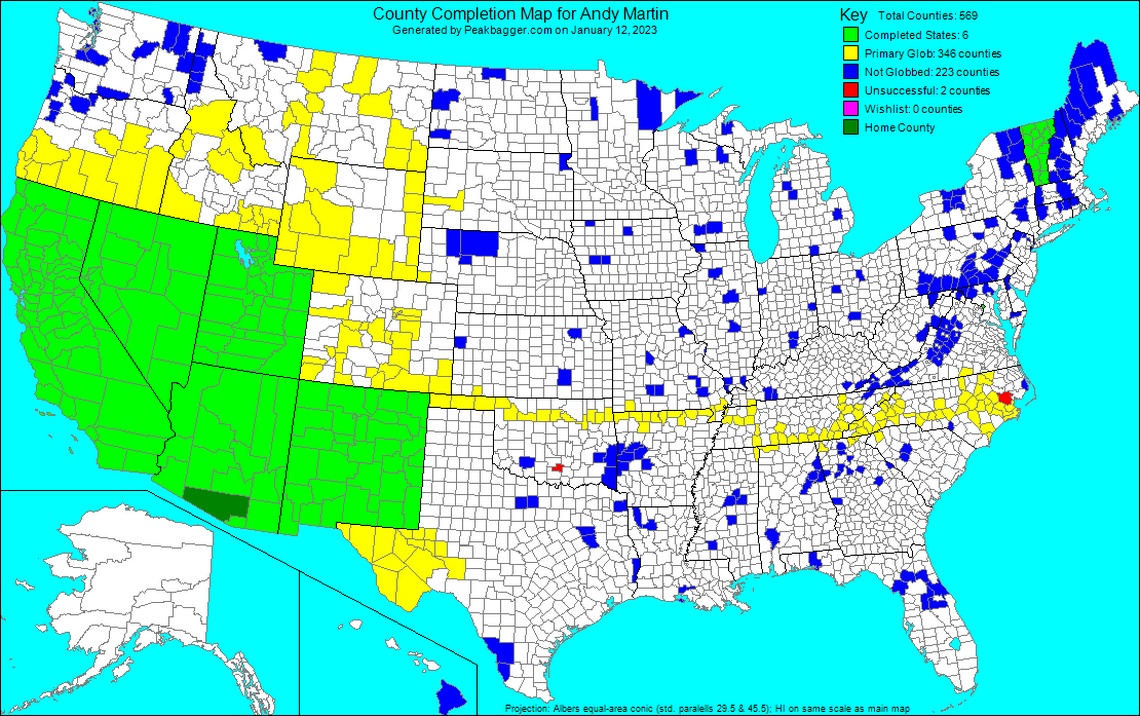

When you shade all those counties on a map, you get a very satisfying glob of color to mark your achievement. In 1999, Andy Martin became the first highpointer to extend his glob across the U.S., from sea to shining sea. Spooky Mike Schwartz was the first to extend his glob into all of the 48 continental U.S. states in 2002.

Covill soon discovered that county highpointing wasn’t all about high altitude thrills. A big part of the hobby — especially in the days before the internet — involved requesting U.S. Geological Survey maps by mail and poring over them to find the high points in Midwestern prairies and Southern swamps.

Nowadays, that information is documented on websites like Peakbagger.com, although some county high points are still hotly debated even in the age of high-tech lidar elevation mapping. Luckily, that kind of obsessive research suited Covill: “I got a great deal of satisfaction out of painstakingly looking at topographic maps,” he said.

Wherever he traveled in the U.S., Covill would research nearby county high points and find time to make a pilgrimage. So it was that in 1999, while visiting his parents at their condo near Naples, Florida, Covill set out to find the highest natural point in Miami-Dade County.

Finding the peak of Miami-Dade County

After studying an exquisitely detailed, 5-foot-by-8-foot topographic map of the county (which he assembled himself by taping together a collection of smaller U.S. Geological Survey maps), Covill identified exactly 56 spots where the land rose at least 20 feet above sea level.

Then, over the course of three days in 2001 and 2002, he set out to visit all of them. His journey took him to the dunes of Virginia Key, the hills of the Doral golf course, the pine rocklands of the Deering Estate, the landfills of northwest Miami-Dade, and a long tour of the southwest suburbs along the coastal ridge that runs through Pinecrest, Coral Gables, and Coconut Grove.

Cliffs, bunkers, mammoth bones: Miami-Dade County’s most intriguing high points

Covill documented all his ascents, down to the minute, in a log posted to cohp.org, a volunteer-run website for county highpointers. He concluded that 26 of the potential high points were landfills, road embankments or other forms of human construction. The two dune areas on Virginia Key were also almost certainly artificial — the result of dredging for nearby shipping channels.

That left 28 (mostly) natural peaks of at least 20 feet, but these were separated by mere inches of elevation and all of them had something built on top of them. “In a nutshell, the [high point] of Dade appears to be one of the 20’+ areas, which no one will ever tell, as every single area over 20’+ seems to me to be man-altered,” Covill concluded in his write-up of the journey.

Five years later, Schwartz recreated Covill’s journey to all 56 potential peaks and became the second (and so far only other) highpointer to submit a cohp.org or Peakbagger.com trip report documenting a journey to every possible high point in Miami-Dade County. At least 39 others have recorded partial attempts, but no one else claims to have gone to every point.

Schwartz says the only reason he even attempted a county as troublesome as Miami-Dade is that he wanted to form a continuous glob that stretched to all four corners of the continental U.S. Plus, he has fond memories of South Florida: He spent several years in the 1970s stationed at Homestead Air Force Base, using a massive antenna near Alabama Jack’s to monitor Cuban radio signals.

Schwartz’s 2006 report on Miami-Dade agrees with Covill’s assessment of the county’s natural and artificial high points and adds one tantalizing guess at what might be the highest peak of all.

“My favorite choice for the true natural high point is Dave’s area #30,” Schwartz wrote, referring to a slight rise near the corner of Micanopy Avenue and Halissee Street in northeast Coconut Grove, “but the relief in [Miami-Dade] is too slight to eliminate all other areas with confidence.”

‘Our silly hobby’

County highpointers sometimes have a hard time articulating exactly why they do what they do.

“To me there’s nothing really deep to it,” said Schwartz. “It’s just something to do. It’s no worse than collecting stamps, or whatever…It gets you out of the house. You get to meet some weird people. You get to run around the country. You get out of your wife’s hair.”

“One of my high point buddies calls it ‘our silly hobby,’ and I think that’s a great description,” Schwartz added.

Some are seeking the order and logic missing from the chaos of their day-to-day lives.

“I think this whole pursuit appeals to goal-oriented people, a lot of engineers, people who have OCD,” said Greg Slayden, a Microsoft software engineer, county highpointer, and the founder of Peakbagger.com. “It feels like you’re adding order to your life by doing this kind of collecting and ticking another box on your list…You feel more complete.”

For others, it’s a way to appreciate the everyday beauty of the land all around them — even in a flat county like Miami-Dade.

South Florida geology 101: Lessons in the rock about future risks from sea rise

“When you get to one of these high areas and you see an outcrop of limestone, you just get this feeling that it’s real,” said Covill. “It’s real rock. It’s Florida’s rock. And it’s just as valid a rock as granite in Colorado and sandstone in Arizona or volcanic rock in Hawaii. It’s what Florida is made of.”

This climate report is funded by Florida International University, the Knight Foundation and the David and Christina Martin Family Foundation in partnership with Journalism Funding Partner. The Miami Herald retains editorial control of all content.