Before the Moskva, there was the Kursk: The sunken submarine that helped Putin consolidate power over Russia

WASHINGTON — Twenty-two years ago, a Russian nuclear submarine sank after being rocked by two explosions during a torpedo test launch gone awry. There were 118 sailors on board the Kursk; most of them died at once. But a few survived, sequestering in a rear compartment that had not been destroyed.

For longtime observers of Vladimir Putin’s rise, it was impossible not to think of the Kursk when the Moskva, the flagship missile cruiser of the Black Sea Fleet, sank on April 14. The two maritime disasters serve as bookends of sorts for the two decades of Russia under Putin’s rule. The first took place shortly after he assumed the presidency, when dreams of a democratic Russia were battered but not yet dead. The second, the victim of his invasion of Ukraine, comes at a time when Russia is an international pariah and Putin faces the deepest crisis of his reign.

“Putin’s presidency started with Kursk; here’s to it ending with Moskva,” wrote Ivar Dale, a Norwegian expert in Russian affairs, on Twitter.

The Kursk taught Putin as much as it taught Russia, giving the young and inexperienced president a tragically clear view of what he had inherited — and of what it would take to maintain power in a crumbling empire that for 10 years had been careening between freedom and chaos.

“Everything that has long since been typical of Putin was demonstrated after the sinking of the Kursk,” investigative journalist David Satter, who was banned from Russia for his reporting on Putin’s rise to power, told Yahoo News. “The xenophobia, mendacity and casual assumption that the lives of people without power have no value.”

Above all, the Kursk disaster taught Putin that a free press had no place in the new Russia, for it could only expose how little had changed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union — and how what had changed was mostly for the worse. There could be freedom or order in the new Russia, he decided, but there could not be both.

“The entire process of undermining democracy in Russia, in many regards, began with this,” the attorney Boris Kuznetsov, who represented some of the Kursk families and later had to flee Russia, said in 2015.

Until the catastrophe, Russia had been on a trajectory encouraged by the West, which saw value in Russia as an unexplored market yearning for investment. The optimism persisted well into the 1990s, even as it was becoming clear that disorder and revanchism were more persistent than Harvard-trained economists had supposed would be the case.

“Russia has a democracy — imperfect, perhaps, but not now seriously threatened — and a free press in which Moscovsky Komsomolets can print biting political cartoons on its front page and Izvestia amuses its readers nominating an oligarch of the year,” Lawrence Summers, then the deputy treasury secretary, said in early 1999, referencing two of Russia’s most famous Soviet-era newspapers.

Of all the changes to come in the years that would follow, the decline of a free press would prove perhaps the most consequential. After the Kursk, Putin worked assiduously to muzzle the country’s independent media, a campaign that came to its natural conclusion when he invaded Ukraine earlier this year.

As the Ukrainians held on in the face of February’s initial assault and pro-Kremlin media sought explanations of why the Russian tricolor wasn’t yet flying atop Kyiv’s spires, Putin moved to quickly shutter his country’s last remaining networks and newspapers, the few still interested in telling the unvarnished truth.

“The Russian media is dead,” a local Russian journalist told Committee to Protect Journalists executive director Robert Mahoney last month.

Putin was remarkably new to Moscow, and national politics, when the Kursk went down. He spent the last years of the Cold War as a midlevel KGB bureaucrat in East Germany. After the collapse of the USSR, he became the deputy mayor of his native St. Petersburg, only to lose that job when his reformist boss Anatoly Sobchak was defeated in a 1996 reelection contest.

Later that year he went to Moscow, assigned to “manage” the transfer of formerly Soviet property assets. He ascended quickly from there to become prime minister in 1999 and president in 2000 — all without ever having won a single election.

Putin had not served in the military, but the poor condition of the armed forces was no secret. President Boris Yeltsin had cut the military budget to only 5% of what it had been during the last year of the Soviet Union, when Red Square parades — troops, rocket launchers, tanks — disguised profound social ills but nevertheless intimidated the rest of the world with their sheer size.

“Not since June 1941 has the Russian military stood as perilously close to ruin as it does now,” a military analyst for the United States wrote in 1994.

Yeltsin had come to power as a reformer, but his liberalizing project made a few oligarchs rich while impoverishing ordinary Russians and turning a superpower into a laughingstock. Long a heavy drinker, Yeltsin was barely functioning by the time he appointed Putin his prime minister and successor.

Consolidating control over the Kremlin even while Yeltsin technically remained his superior, Putin oversaw Russia’s response to a series of apartment bombings in 1999 that many experts believe were carried out by Moscow’s own security services, perhaps at Putin’s own direction. The attacks were used to justify an invasion of Chechnya, a small, majority-Muslim province that had tried to break away from Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union a decade before.

Afraid that other autonomous republics would follow suit, Yeltsin invaded Chechnya in 1994, expecting an easy victory. But the Chechen rebels exploited Russian military disorganization and corruption, much as Ukrainian fighters have in recent weeks. After a disastrous attempt to take the Chechen capital city of Grozny — allegedly ordered during a bout of drinking — Russia withdrew in 1996, having effectively been defeated.

Putin was determined to win back Chechnya, and allowed his generals to do whatever they needed to do as long as they emerged victorious. “Mr. Putin is benefiting from the licensed brutality in Chechnya,” the Guardian noted in February 1999, quoting a top Russian commander’s unambiguous warning of mutiny to the Kremlin: “Russia’s officer corps just can’t take another slap in the face. There are even some who think that such a turn of events would put Russia on the brink of civil war.”

Putin sanctioned the heavy bombing of Grozny without regard for civilian casualties. On March 20, 2000, as the then-acting president was about to face his first election, Putin landed in a fighter jet in Grozny to proclaim victory. Yeltsin had failed to take Grozny in two years. Putin did it in less than six months.

On August 10 of that year, the Russian navy commenced exercises in the Barents Sea, a body of water south of the Arctic Ocean. The exercises, called Summer-X, involved more than 30 craft, including four submarines and the flagship of the storied Northern Fleet, Pyotr Velkhi (Peter the Great). Western intelligence services watched Summer-X with “high anticipation,” journalist Ramsey Flynn wrote, as “a key test of an emerging do-more-with-less defense philosophy of Russia’s little-known new leader.”

The Kursk went down shortly before noon on Aug. 12, likely because of a hydrogen peroxide leak during the launch of a test torpedo that caused a pair of explosions. After the second, much larger explosion, it came to rest in about 350 feet of water.

Western intelligence services had picked up strange seismic activity that they realized was something gone wrong in the Summer-X exercises. They quickly reached out to their Russian counterparts, only to be rebuffed. The Northern Fleet’s confidence was deeply misguided. “The Russians did not have the ability to reach the sub to conduct any type of rescue/extraction operations,” a subsequent U.S. intelligence report concluded. That same report said it took the Northern Fleet three-and-a-half hours to realize that something had happened to the Kursk.

Vyacheslav Popov, the top Russian admiral aboard the Pyotr Velkhi, seemed to show little concern for the submarine’s fate, even as it was becoming increasingly clear that something had gone wrong. If a Western military would have responded with an all-hands-on-deck rescue, the Russian armed forces had never recovered from the trauma of Stalin’s brutal purges of the officer ranks during the 1930s. Secrecy and silence had been crucial to survival in that era — and they were still, even in a supposedly new age of freedom.

“Confronted with what seemed like evidence of a huge disaster, Popov did what a long line of senior officers and politicians had done before and after him. He did nothing,” the historian Peter Truscott wrote in his book about the Kursk. The Northern Fleet did not declare an emergency until that evening, nearly 12 hours after the Kursk had gone missing.

Putin had left for Sochi, the Black Sea resort beloved by his Soviet predecessors, on the 12th. Only the next morning did his defense minister call with the bad news. Only on the 14th did the Northern Fleet admit that something had gone wrong on the Kursk, grossly underplaying the severity of the crisis and refusing to say who was on board. By then, dark rumors were already circulating among submariners’ families.

It would take days for Russian authorities to admit that the submarine had sunk, and that virtually nothing was known about any survivors, in large part because initial Russian rescue attempts had been so hapless.

Putin remained in Sochi, while the press in Moscow assailed him for his inattention to the crisis. “He was in a stupor,” a Kremlin source would tell the journalist Catherine Belton. “He didn’t know how to deal with it, and therefore he avoided dealing with it.”

Norway and the U.K. offered their own deep-sea experts and equipment, as did the United States. Putin and his admirals refused their offers, not wanting to admit how inferior their own rescue equipment was. They also held on to Soviet-era notions of secrecy, fearing that if Western divers were allowed access to the Kursk, they would steal its military secrets.

At the same time, grief and rage scored Russian media.

“The reputation of the Russian leadership is lying on the bottom of the Barents Sea,” read a headline in one Moscow newspaper.

“Lies and fear are the features of Russian authority. Russia has been persecuting and punishing its people for so long that by now it has simply forgotten how to save their lives,” said the newspaper Izvestia, which had been a reliable Kremlin mouthpiece during the Soviet years.

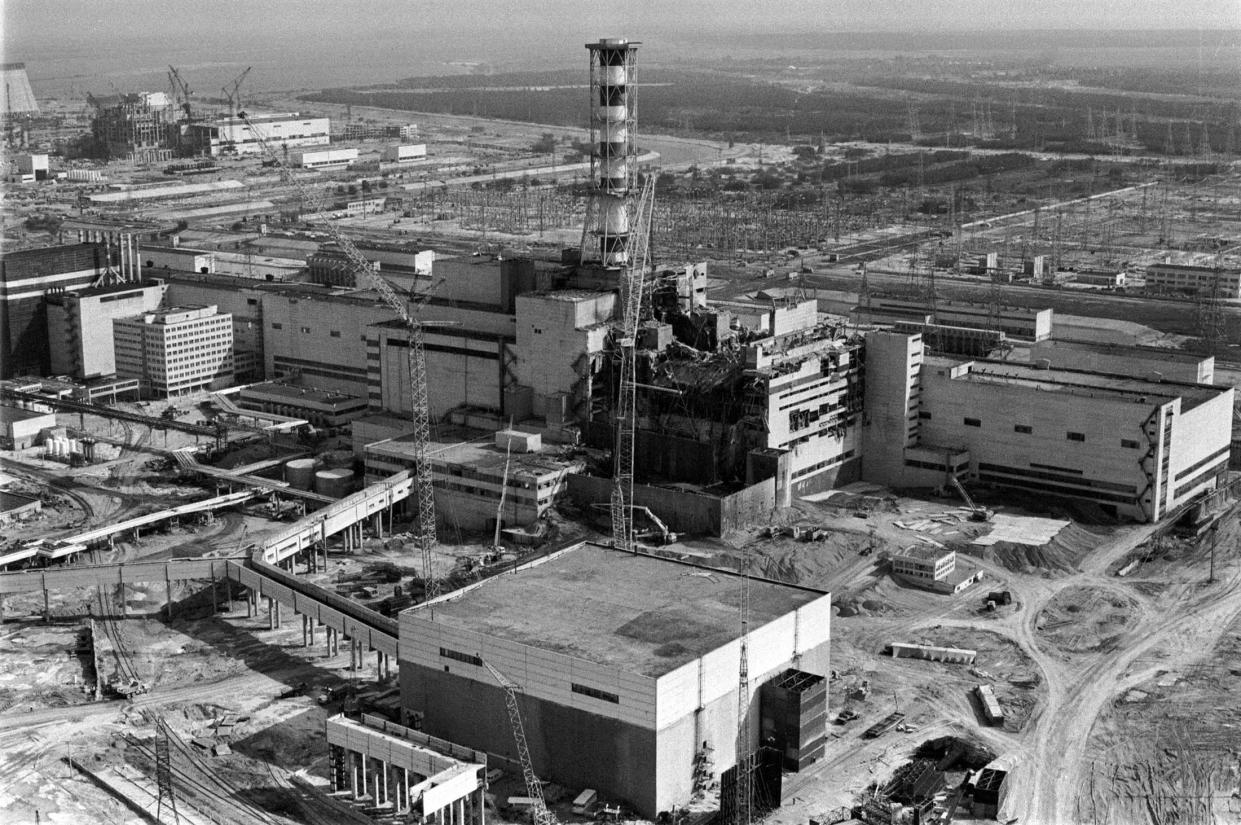

“All this reminds us of Chernobyl,” the journalist Zinaida Lobanovna wrote in Komsomolskaya Pravda, referencing the 1986 nuclear disaster that was partly responsible for the Soviet Union’s downfall.

Putin recognized that more than military incompetence or public anger, it was negative coverage that could doom his young presidency. “President Putin learned to appreciate the media’s power to shape public opinion and that the stinging criticism he received could only be checked by controlling the press,” military scholar Zoltan Barany has written.

By the time Putin arrived at the Kursk base on the remote Kola Peninsula, on August 20, it had already been more than a week since the Kursk sank. He didn’t have any new explanations, but he did have a new story — and new scapegoats.

“One witness at the closed meeting said Mr. Putin referred three times to the media’s treatment of the crisis, and raged at tycoons who had allegedly robbed the nation and were now manipulating public opinion,” went one report from the town hall, which was closed to the press but made the newspapers anyway.

“The government had not been guilty of deceit and incompetence during the crisis, Mr. Putin told the families. The media had created such an impression.”

Later, Putin preposterously fumed that the grieving mothers he encountered were actually local prostitutes hired by the oligarch Boris Berezovsky, who had been close to Yeltsin and who ran the immensely influential ORT television network. Berezovsky was one of the two oligarchs Putin blamed for how the Kursk was covered. The other was Vladimir Gusinsky, who ran the Media-Most empire.

“They stole money, they bought the media and they’re manipulating public opinion,” Putin said of the two oligarchs, in a message intended less for the grieving families than for the power elites hundreds of miles away in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Many of the other oligarchs were also Jews; they had suddenly come to power in a country with a long history of antisemitism.

Some had an obvious interest in politics, like industrialist Mikhail Khodorkovsky; others only in media or industry. Their backgrounds or ambitions notwithstanding, they represented the excesses and possibilities of the Yeltsin era. That era was now coming to an end.

Probably the single most arresting episode from the entire Kursk crisis was that of a grieving mother shouting at officials who kept offering explanations, apologies and assurances, each more obfuscatory than the next. “This is a disgrace!” the mother can be seen and heard shouting in surreptitiously recorded video, her cries overflowing with pain. As she continues to berate the Moscow minister before her, a woman approaches from behind, plunging a syringe full of sedatives into the mother’s back.

“The incident was broadcast extensively yesterday, to the acute embarrassment of President Vladimir Putin's government,” a Guardian report noted.

Several top military officials tried to resign, but Putin prevented them from doing so. “He was no longer entitled to seethe at the people who had destroyed Soviet military might and imperial pride,” the journalist Masha Gessen would write later. “By dint of becoming president, to a great number of his compatriots he had now become one of those people.”

A little less than a month after the Kursk sank, Putin traveled to New York for his first meeting of the United Nations General Assembly. While in New York, he sat for an interview with Larry King, then the host of a popular CNN news program.

“Tell me,” King asked, “what happened with the submarine?”

Russians have never forgotten the haunting, puzzling smile that crossed Putin’s face, or the two words he offered in response: “It sank.”

The admission was as puzzling as it was frank. The “crumbling edifice of a former superpower” was now his to deal with, Gessen wrote, and there was a certain political audacity to admitting as much.

Families of the Kursk victims received unusually generous compensation packages, angering some families of soldiers killed in Chechnya, as well as some soldiers still fighting there. “If you count the boys who died here, the entire nation should be mourning for a year without stopping. But no one cares for us, nor pays us honor when we die. The commanders think that it’s our job to die here," a 20-year-old sergeant said.

At the same time, Putin moved quickly to reverse the freedoms of the Yeltsin years, which threatened to topple his embattled administration. Accountability and frankness could only take him so far.

“A recurrence of self-censorship among Russian journalists is proving to be perhaps the most destructive consequence of the events of the past 12 months, and one that will be extremely difficult to overcome,” warned two Russia observers in a New York Times op-ed in January 2002.

Two years later, the assassination of journalist Anna Politkovskaya marked a dangerous new era for anyone in Russia who sought to expose the truth. The new mood allowed the Kremlin to control coverage of crises like the 2004 siege of a school in Beslan, as well as abuses by Russian troops in Chechnya and virtually unchecked corruption on the part of Moscow and St. Petersburg elites.

Khodorkovsky, the outspoken oligarch, went to prison in 2005 on fabricated charges of financial malfeasance. Trying to expose the Kremlin’s own corruption, the tax attorney Sergei Magnitsky died after being abused in prison, where he’d be sent on charges as fictitious as those that had been used to convict Khodorkovsky.

By the time Putin first invaded Ukraine in 2014, his control of the media was almost complete, feeding the Kremlin’s grievances and illusions to millions. And as Russia amassed troops on the Ukrainian border in 2021, Admiral Popov, now retired, resurfaced to claim that the Kursk had in fact been sunk by a NATO craft.

That wasn’t true, and Russian authorities had always known as much. In fact, back in 2001, they had been frank — however fleetingly — in their assessment of their own official incompetence. But in 2022, things were different: There was no one around to correct the lie.