Money was promised to her after brain injury. But SC judges let most of it go to companies

After a train crashed into her mother’s car, Grace was airlifted to the hospital and placed in a medically induced coma.

Doctors drilled a hole through the 12-year-old’s skull to relieve the pressure building around her brain. She was in the coma for nearly a month, followed by physical therapy, relearning how to walk, talk and feed herself.

The train company eventually settled Grace’s personal injury lawsuit with most of the proceeds placed in a structured settlement, a type of financial arrangement with money to be paid to her in monthly, tax-free installments for the rest of her life. The money would provide her a steady income because her traumatic brain injury was likely to limit her ability to earn an income in the future, her family was told.

But Grace, now 30, has stopped receiving her monthly checks and won’t see another dime until she’s at least 60 years old. That’s because several private companies were allowed to purchase Grace’s future payments in exchange for giving her immediate cash.

S.C. judges, charged with looking out for Grace’s best interest, signed off on the companies buying her future payments in a series of deals. In the last one, a judge signed off on allowing Grace to give a company more than $87,000 of her future payments for about $8,500 in immediate money.

Grace spent it. Now, short on cash and with limited job prospects because of her injuries, she may lose her home and faces an uncertain future.

Each year, hundreds of South Carolinians who receive structured settlements sell their future payments and forfeit their stable financial futures, a McClatchy investigation has found. In the most worrisome cases, the lightly regulated companies, often called structured settlement factoring companies, buy the payments from sellers who have traumatic brain injuries or other debilitating injuries and rely on the settlements to make ends meet.

Safeguards put in place by the state legislature to protect sellers, including a requirement that judges sign off on the deals, stop very few from gaining approval. More than 94% of the deals that reached a hearing before a judge between 2014 and 2021 were approved, according to the newspaper’s analysis.

While the deals are legal, there are questions about how closely they are scrutinized by the courts, according to the newspaper’s look. If the judges had closely reviewed Grace’s case, for instance, they would have learned that the girl who once excelled in advanced classes qualified for special education services after the train wreck. Her IQ tested in the first percentile, court records show. And at home, she had short-term memory loss, which remains one of several challenges.

“I usually write stuff down so I’ll remember it,” Grace said in a recent interview. “I be forgetting stuff so fast, like when my doctor appointments are and everything.”

Meanwhile, the fast cash sellers receive often doesn’t account for much.

The newspaper analysis of more than 1,400 of these deals approved between 2014 and 2021 in South Carolina found sellers received, on average, lump sums worth about 25% of the sold future payments.

More than $228.6 million in future payments were exchanged for less than $58 million in lump sums. The discounted present value of those payments — a calculation based on a federal rate that assumes money in the future is worth less than the present — was estimated at more than $157.3 million. The present value was redacted from public records in many cases, preventing the newspaper from listing it on several deals mentioned in this series.

The immediate money doesn’t last long. Many sellers interviewed by McClatchy say they now regret their deals and are in worse shape financially as a result. Public records show many have faced evictions and other financial hardships.

“These people, they’ve been horribly injured, the system is trying to protect them, and now they’re just getting hammered,” said Eric Vaughn, executive director of the National Structured Settlement Trade Association, which represents the consultants, attorneys and insurance companies that help set up these settlements.

“These deals are just terrible. Maybe 1 in 10,000 might help somebody stave off a missed mortgage payment, but the rest of them are just awful ... and they leave them completely destitute when it’s all done.”

JG Wentworth, the largest and most well-known purchaser, and other factoring companies did not respond to McClatchy’s requests for interviews. But industry advocates tout the benefits these deals offer structured settlement holders in need of liquidity, noting banks don’t consider these future payments as an asset when applying for loans.

“These transactions can certainly be valuable for folks who are wanting to buy a house … or starting a business, or want to get out of debt,” said Brian Dear, executive director of the National Association of Settlement Purchasers, a trade group that represents many of the nation’s largest factoring companies other than JG Wentworth.

Courts sign off on each sale, ensuring they’re sound deals for the sellers, Dear noted.

“The court-reviewed process is important because we want to make sure people involved in these transactions (that) a third party reviews it to make sure these individuals know exactly what they’re doing, (and) they’re going to be using this money for a good purpose.”

S.C. law requires that each deal be approved by a judge who must find it’s in the seller’s “best interests.”

But the newspaper determined that the factoring companies employ a small group of S.C. attorneys who seemed to have developed a specialty in presenting the cases before select judges who approve nearly every deal. Meanwhile, the sellers typically have no lawyer representing them in court.

The cases are sometimes heard in courtrooms far from where the sellers live and the structured settlements were reached, McClatchy’s analysis found, raising questions of forum shopping.

State lawmakers have done little to police the industry, passing a law to protect those with structured settlements 20 years ago, but not updating it since. This, even though lawmakers in many other states, including Minnesota and Florida, have made changes in recent years to clamp down on the questionable practices of the companies.

S.C. legislators, informed about McClatchy’s findings, have said they were stunned and plan to follow the lead of other states in addressing these issues.

“This is shockingly predatory and screams for reform,” said state Sen. Luke Rankin, the Horry County Republican who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Worsening the toll, South Carolinians who sell their future payments rarely stop after just one deal — often continuing to sell payments once their fast cash is gone, McClatchy found.

A Colleton County judge first approved one of these deals for Grace in August 2018, transferring $22,800 in future payments for about $6,500.

She had recently used some of her settlement money to buy a house, placed behind her mom’s house on the same property. But she needed the money to complete its septic tank, Grace told the judge.

“I was going through so much stuff trying to finish it and everything,” she recently recalled in an interview with McClatchy. “I thought (the money) would help me.”

But the deal was just the beginning. Grace signed agreements with factoring companies 16 more times during the next three years, and every deal was approved by a judge or special referee, an attorney appointed to serve as a judge in certain cases.

Her 17th and final deal was approved last November.

Afraid of losing her house, Grace finally broke down and told her mom what she’d done just before the holidays. But it was too late.

December 2021 was the first month she didn’t receive any of her monthly structured settlement payment.

That check for $1,890.89 set to arrive in Grace’s mailbox on the 14th of every month was instead directed to a P.O. Box in Philadelphia, Orlando or Woburn, Massachusetts through November 2051. The future payments sold totaled $692,110.

“When she got the (structured settlement), … I thought (it) was designed to protect her from throwing away the money,” said Jocelyn, her mom.

Grace and Jocelyn are pseudonyms for the mother and daughter, used at their request to protect their identities.

“And I thought the whole purpose of her going through a judge was to protect her from stuff like this,” Jocelyn continued. “Obviously it ain’t. The judge didn’t serve a purpose cause anyone with common sense can see that something was happening that wasn’t supposed to. It didn’t make sense. Seventeen times?”

Targeting the young

Austin Clayton, like most other sellers who spoke with McClatchy for this story, learned he could get immediate cash for his future structured settlement payments from watching JG Wentworth commercials.

“I was a struggling kid out of high school, and it just got my attention — get cash now. It sounded pretty good,” the 27-year-old Laurens County man said.

The structured settlement was set up for Clayton after he was in a wreck in middle school that ejected him from a car and nearly killed him. He suffered two severe brain injuries, multiple broken ribs, bruised lungs, bruised kidneys and a shattered shoulder, he said.

Clayton said he saw the commercial as an opportunity to fulfill his lifelong dream of owning a business. In 2013, a 19-year-old Clayton agreed to transfer $35,000 of his future payments to the company in exchange for $16,400.

He used the money to start a painting and pressure washing business with a friend, but within six months, he had nearly run out of money and was in danger of losing the business. So he decided to dip back into his structured settlement.

Frustrated with JG Wentworth — who he said promised to teach him to start his business but then disappeared once the deal was approved — he took his business to another factoring company, Stone Street Capital.

“JG Wentworth (made) a promise they would help me start the business, teach me what I didn’t know … and give me money for it,” Clayton said. “I tell you right now, don’t you ever listen to none of them people. They’ll let you down every time.”

Stone Street was one of the larger factoring companies in the U.S. at the time, but it has since been bought by JG Wentworth. Stone Street representatives agreed to give Clayton just over $18,000 in exchange for more than $54,000, which represented the rest of Clayton’s future payments, and teach him about buying a home, he said.

When he spent that money on rent, bills and business expenses less than six months later, Clayton said he was left with nothing — he lost his business, had to sell his truck and struggled to pay bills for years. He’s still never owned a house, he added.

Clayton now calls those deals his biggest regrets in life.

“They took advantage of me,” he said. “I was just a dumb kid and didn’t know what I was doing.”

Being young with limited financial know-how was how many sellers described themselves in interviews when asked the reasons they pursued the deals.

Participants’ ages were rarely disclosed in court documents. But multiple S.C. judges and special referees who frequently oversee these transfers told McClatchy younger sellers were most common.

“I haven’t heard many where the people are up in years,” said Judge Haigh Porter, master-in-equity for Florence County. “I’ve had them in their 50s, a few in their early 60s, but I would say the majority of those I’ve heard in recent years have been under 35 or 40 at most.”

Former Judge Jack Kimball, retired master-in-equity for York County, said he commonly saw sellers between 18 and 20 years old, noting they usually received the settlements as minors and only start receiving payments once they became adults.

“Some of them just wanted to buy a car, and I typically wouldn’t approve that because you know darn well the car wasn’t going to last,” he said.

Aggressive marketing?

While catchy commercials often convince people with structured settlements to reach out to the factoring companies, most sellers described an onslaught of marketing directed at them once they complete their first deal.

“These people are like roaches,” Jocelyn said, describing the constant phone calls and mail her daughter receives from factoring company representatives, even though Grace’s future payments are sold through the year 2051. “They had it so bad, these people was calling my phone looking for her when she didn’t pick up.”

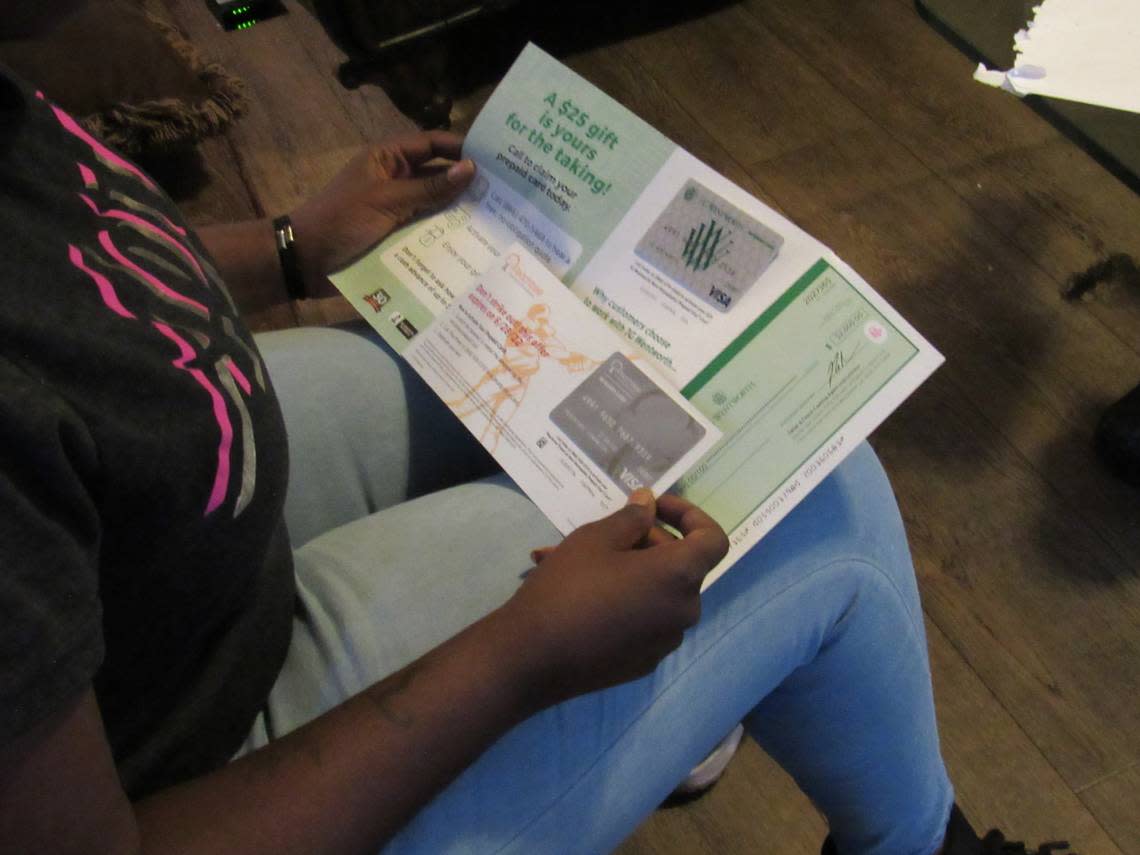

While being interviewed in June for this story, Grace walked to her mailbox and found letters from JG Wentworth and Peachtree Financial Solutions, a subsidiary of JG Wentworth, with checks and prepaid Visa gift cards urging her to call them to activate them.

These are common tactics used by factoring companies to get potential sellers on the phone, industry experts said, but the checks and gift cards actually just serve as advances if the person agrees to move forward with selling their future payments.

Akida Ivory, a Charleston man who completed three deals with JG Wentworth and other factoring companies between 2014 and 2018, was so wary of these companies’ marketing tactics that he was convinced a McClatchy reporter calling to interview him for this story was a factoring company employee trying to collect information about him to convince him to sell more of his future payments.

“The only people who call me are people who want my money,” he said. “I don’t even go to my mailbox anymore because 80% of the envelopes in there contain offers to buy my payments.”

Columbia attorney Robin Alley, who represents JG Wentworth and its affiliates for deals filed in South Carolina, said he has seen several instances when smaller, “unscrupulous” companies contact sellers who have entered into contracts with his clients, offer them “what looks like more money,” and then convince them to allege harassment by the original factoring company.

Dear similarly attributed much of the harassing marketing to “bad actors” in what’s become a very competitive industry.

He said his association advocates for state legislatures to require factoring companies to register to do business and be regulated by a state agency, which he believes cuts down on those practices, and gives sellers being harassed an easy avenue to hold those companies accountable.

Those provisions, along with restrictions on companies’ ability to contact people already under contract to sell their future payments, have been added to structured settlement protection acts in Georgia, Louisiana and Nevada in recent years.

Protecting their ‘best interests’

South Carolina’s Structured Settlement Protection Act, enacted in 2002 and untouched since, puts the onus on judges to ensure deals are in the seller’s best interest. But interviews with judges show there is no consensus on what “best interest” means.

“We would talk about them at the annual judicial conference, talking about the structured settlement (transfers), and you’d get (fellow judges’) opinions of it,” said Kimball, the retired York County judge. “’How do you treat it?’ ‘What do you do?’ And I know one judge, who is also retired, who would never approve them, and another judge who is retired who would always approve them, all of which seems pretty arbitrary.”

Most of the deals in South Carolina go before masters-in-equity or special referees, according to court documents reviewed by McClatchy. Masters-in-equity are judges appointed by the governor in individual counties to six-year terms that rule in non-jury matters — most often foreclosure filings and other real estate-related issues — referred to them by circuit courts.

Only half of South Carolina’s 46 counties employ a master-in-equity, so in counties without one, the transfers are instead often reviewed by special referees, attorneys appointed by a circuit court with the same powers as a master-in-equity to oversee an individual non-jury matter.

Judges and special referees told McClatchy they have a list of questions they typically ask and factors they consider, including sellers’ plans for spending the money, their other sources of income and their education level.

“I’m very skeptical when (settlement payments are) their primary means of support,” said Judge Jeffrey Tzerman, master-in-equity in Kershaw County. “But I got to balance that against the right of a person to do what they want.”

McClatchy’s analysis found that more than 94% of the cases that reach a hearing are still getting approved, raising questions about the level of vetting that occurs. Several judges and special referees indicated they were inclined to let people make poor decisions as long as they felt confident the seller understood what they were doing.

“I don’t think it’s depriving … them of something against their free will,” Kimball said. “I don’t like (the deals), just seems sort of sharkish, but if a judge does what I view to be the judge’s job, … (the sellers are) entitled to make a stupid mistake. We’re all entitled to make stupid mistakes.”

Some admit they don’t ask many questions, including why a seller got the settlement in the first place, which may mask traumatic brain injuries and the need for a guardian ad litem, a court-appointed advocate who conducts an independent investigation to make a recommendation about what’s in a seller’s best interest.

None of the judges or special referees Grace appeared before asked her about the train crash or her traumatic brain injury, she said.

That recollection couldn’t be checked against court hearing transcripts because a court reporter is rarely present in hearings, according to numerous judges and special referees interviewed.

“Usually if it’s not contested, in any type of case, they don’t have a court reporter,” said Judge Walter Sanders, master-in-equity for Allendale County.

Sanders, who approved three of Grace’s deals, spoke to McClatchy in April about how he handles these cases generally, but did not respond to numerous requests for a follow-up interview that would have included specific questions about Grace’s deals.

Judges Elbert Duffie and Harriet Bonds, a pair of Colleton County magistrate judges that approved six combined deals for Grace while serving as special referees, did not respond to requests for interviews.

Grace disclosed her traumatic brain injury in an affidavit attached to one of those cases approved by Bonds, court records show.

Her other eight deals were approved by Colleton County special referee Benjamin Sapp, who told McClatchy he did not know Grace had been in a train wreck or had a brain injury.

He said the only question he typically asks is why the seller wants the money, and if it is for a “compelling reason,” he approves the deal.

When asked how he determines a seller is competent to understand what they’re doing, Sapp said in a May interview that he talks to their attorney about their education level.

But the sellers are almost never represented by an attorney in these deals, including none of those who appeared before Sapp, according to court records. He was actually referring to the attorneys who represent the factoring companies.

“The attorney that is trying to get the structured settlement (transfer) approved is representing that person, he’s got to be representing them,” Sapp contended when challenged by a McClatchy reporter that sellers didn’t have representation.

Richard Steadman, the North Charleston-based attorney who represented factoring companies in all of Grace’s transfers brought before Sapp, confirmed to McClatchy that he only represented the companies, not the sellers.

When reached again in July, Sapp said he had spoken to Steadman since the initial interview, and he had misspoken and understood no one represented Grace.

Asked again how then he determined she was competent to understand the deals, Sapp responded: “I asked her questions, does she know what she’s doing and all that. … It’s her money, sir.”

Steadman, who represented the companies in 14 of Grace’s deals, told McClatchy he couldn’t recall being aware of her traumatic brain injury despite serving as the attorney in the one case where that was disclosed in an affidavit.

DRB Capital, the Florida-based factoring company that Steadman represented in 10 of Grace’s deals, did not respond to requests for an interview.

Dear, executive director of the National Association of Settlement Purchasers, which includes DRB Capital among its members, said it’s in everyone’s best interest for extra precautions to be taken when sellers have brain injuries or mental health issues.

He cautioned that if sellers never disclose their condition, it might not be noticeable and therefore never considered. But if it’s obvious, Dear suggested the court appoint guardians ad litem to advocate for them.

Minnesota recently added a provision to its law, requiring judges to appoint independent advisors to represent the best interests of sellers with known mental health issues. That came in response to an investigative series by the Star Tribune newspaper, Unsettled, which inspired McClatchy’s investigation in South Carolina.

Alley represented JG Wentworth subsidiaries Peachtree Financial Solutions and Stone Street Capital in three of Grace’s deals. He also said he wasn’t aware of her brain injury.

Just keep selling

Grace’s 17 approved deals were the most involving a single South Carolina seller, McClatchy found. But she’s not an outlier in terms of completing multiple transactions. Factoring companies regularly pursue multiple deals with the same person, according to industry experts.

More than 63% of the deals completed between 2014 and 2021 in South Carolina involved sellers who sold future payments multiple times, according to McClatchy’s analysis. That percentage is likely an undercount since the analysis didn’t consider sellers who completed other transfers prior to 2014.

A former senior official with a factoring company previously told the Washington Post this is part of a strategy to target people who have already sold payments — with detailed information on them compiled into a database — often getting them to give up the rest of their future payments within a few years.

Some sellers interviewed by McClatchy explained that after the money they received from an initial deal is spent, they feel pressure to keep selling more future payments.

Angela St. Jean was a struggling single mother of an 11-year-old boy when she called JG Wentworth in 2012 to sell some of her future payments — $65,400 in exchange for $28,000.

“It was an instance of me trying to get on my feet and trying to take care of my son,” she said. “It was a bad decision, and I wish I’d never done it.”

St. Jean had received her settlement from a near-fatal 2002 car accident that left her with 18 broken bones, a 10-day hospital stay and required five surgeries on her right arm alone.

The influx of cash helped for a bit, but once it was gone, and her monthly checks were reduced, the Berkeley County woman felt the need to sell more.

Her second deal in 2013 actually produced a better discount rate — $35,000 in exchange for $62,000 in future payments. But she found what most others do in her third and fourth deals: that companies offer significantly less for payments that are farther into the future.

That’s particularly true when some of those payments are life-contingent, meaning the monthly payments are only distributed if the structured settlement recipient is still alive. That was the case with all the payments included in St. Jean’s final two deals.

In exchange for about $272,000 in future payments across both transactions — and an estimated discount present value of more than $166,000 — she received $30,000 total.

“If I hadn’t done that first one, there’s no way I would’ve ever done it again,” St. Jean said.

Brennan Neville, assistant general counsel for Berkshire Hathaway’s structured settlement arm, said the prevalence of structured settlement recipients selling future payments multiple times in a short timespan is among the most troubling issues he witnesses.

“We recognize that sometimes people do run into hardships and things happen, … but at the same time, if they’re doing it four, five, six, seven times in a row, in short succession, that’s maybe indicative of poor money management, or maybe somebody in their lives that is using them as an ATM,” Neville said.

“Particularly when a younger payee goes through their payments so quickly, and they’re left with pennies on the dollar and nothing left from a structure that was supposed to give them support for 30 or 40 years, those are really, really hard to hear.”

Judges and special referees in South Carolina generally agreed with that sentiment, suggesting in interviews with McClatchy that they’re less likely to approve deals for sellers who have previously sold part of their structured settlement, particularly if they can’t provide a good explanation for how they spent that money.

“The Court considered that this is the second sale of benefits made by the co-applicant who indicated to the court that she told the last Judge that she was going to purchase a house and that she received $125,000 … and has never purchased a house,” an Orangeburg County judge wrote in a rare 2016 denial order.

Orangeburg County denial by David Weissman on Scribd

But the companies and their attorneys aren’t required to disclose previous deals in South Carolina, per state statute, and many don’t, according to a review of court records. Several states have added provisions requiring such disclosures in recent years.

Columbia attorney Tucker Player, who frequently represents factoring companies in these transactions, admitted that provision would be unpopular among the companies he represents, but judges should always have that information to make an informed decision.

Judges who find out about previous deals will typically ask how they used the money they were given, and if they don’t have a good answer, that’s good cause to deny the deal, Player explained.

“Quite frankly, without that requirement, if I’m representing my client zealously, I don’t want the judge to know,” he said. “You see the dilemma that the attorney’s in? Because there’s no requirement to disclose it unless the judge asks.”

Player added that if a judge asks about previous deals, “you better tell” the truth. But a McClatchy reporter witnessed one attorney fail to pass on that information when a judge requested it.

A Florence County woman had already sold more than $8.5 million of her future payments in six deals before appearing at a virtual hearing in May before Judge Clifton Newman. Peachtree Settlement Funding wanted to buy $3.6 million of the 31-year-old’s future life-contingent payments for $12,000.

After Alley, who represents JG Wentworth and its affiliates for deals in South Carolina, gave Newman an overview of the deal, the judge began questioning the woman, eventually asking if she had previously sold any of her settlement.

“No sir,” she responded.

Alley, who should have known that was not true because he previously represented a factoring company on one of her approved transfers in 2018, didn’t say anything as Newman continued his questioning.

Later asked why he didn’t correct the record, Alley told McClatchy he didn’t hear her say that.

While judges would likely recognize sellers who repeatedly appeared before them, McClatchy’s review found that sellers often appear before different judges in different counties, lessening those odds.

Grace’s quest to restore her financial future

Grace and Jocelyn are now working with Sue Berkowitz, director of the South Carolina Appleseed Legal Justice Center, to undo as many of her deals as possible.

Sapp, the Colleton County special referee who approved eight of her transfers, recalled that Grace called him upset with the deals, but he told her there was nothing he could do.

“I’m just a cog in the wheel,” he said.

Berkowitz expressed “disgust” after digging into the details of Grace’s interactions with the factoring companies and how the courts handled her deals.

“It’s as if she was an ATM for these companies,” she said. “(Structured settlements) are set up this way because you know someone’s going to need this help for the rest of their life. … The fact that within three years, all the money has been taken from her — it’s just unconscionable.”

Recently asked how she believed the transfers worked, Grace paused for several seconds before responding: “I don’t know. (The company representatives) made it (sound) like it was an investment to my lifetime, like it would help me. … They made it like it would be helpful to my future, and that in the future, they would give me more money and all kind of stuff.”

The companies purchased more than 30 years worth of Grace’s monthly payments — $692,110 in future payments in exchange for about $126,300 in lump sums, according to court records.

Many others in South Carolina sold more in terms of the total value of the future payments, but none completed as many transactions as Grace.

Steadman said he was always amazed at how frequently Grace kept coming back, but said she always had good reasons for why she needed the money. He declined to detail what reasons she gave.

Sapp recalled most of her reasons had to do with issues related to her house, such as roof and air conditioning repairs.

Grace never moved into her house because it still needs a septic tank, the same reason she first sought the fast cash.

Recently, she walked with a noticeable limp in the June heat through the tall grass behind her mom’s house and toward a tan mobile home sitting atop cinder blocks.

She has a drop foot on her right side since the train crash, an underlying symptom of a neurological issue that makes it uncomfortable to stand very long.

Beside the house with dark green shutters stands a pile of sand and rocks about five feet high and a dozen thick, white pipes.

They are the product of various contractors Grace hired to install the septic tank, but they each took off after she paid them up front.

“I kept telling her, ‘Don’t pay people until it passes inspection.’ But she would pay them ahead of time,” Jocelyn said, audibly exhaling. “That house has been sitting there going on five years … The lights have never been on.”

The smell of fresh paint is apparent as soon as Grace opens the door, immediately turning into a room with a queen bed frame and some tacks on the floor.

“This is why I bought the house,” she proclaims proudly, gesturing with both arms to side-by-side doors with a walk-in closet on the left and full bathroom on the right.

She smiles, explaining that she wanted to put red and blue furniture throughout her living room, while painting her entire room pink.

“I had lots of plans,” she says, briefly looking dejected before quickly picking herself back up.

“It’s still gonna happen. I ain’t gonna doubt myself now.”

Former Island Packet reporter Sam Ogozalek contributed to this reporting.