'It's our money': How Kentucky lawmakers decided where to spend $137 billion

For Andrew McNeill, the reason Kentuckians should care about the state’s budget — all $137 billion of it — is obvious.

“It’s our money that they’re spending.”

And McNeill should know: He was the deputy state budget and policy director under Gov. Matt Bevin and now serves as the president of Kentucky Forum for Rights, Economics and Education, a free-market policy think tank.

Crafting Kentucky’s budget is a complex process that takes place every other year. That makes budget sessions like the one that wrapped up in April particularly high stakes.

Even though Kentucky has a record-high budget surplus, the budget attracted plenty of controversy.

Democrats and other advocates said the budget did not spend enough money on social programs like education and affordable housing.

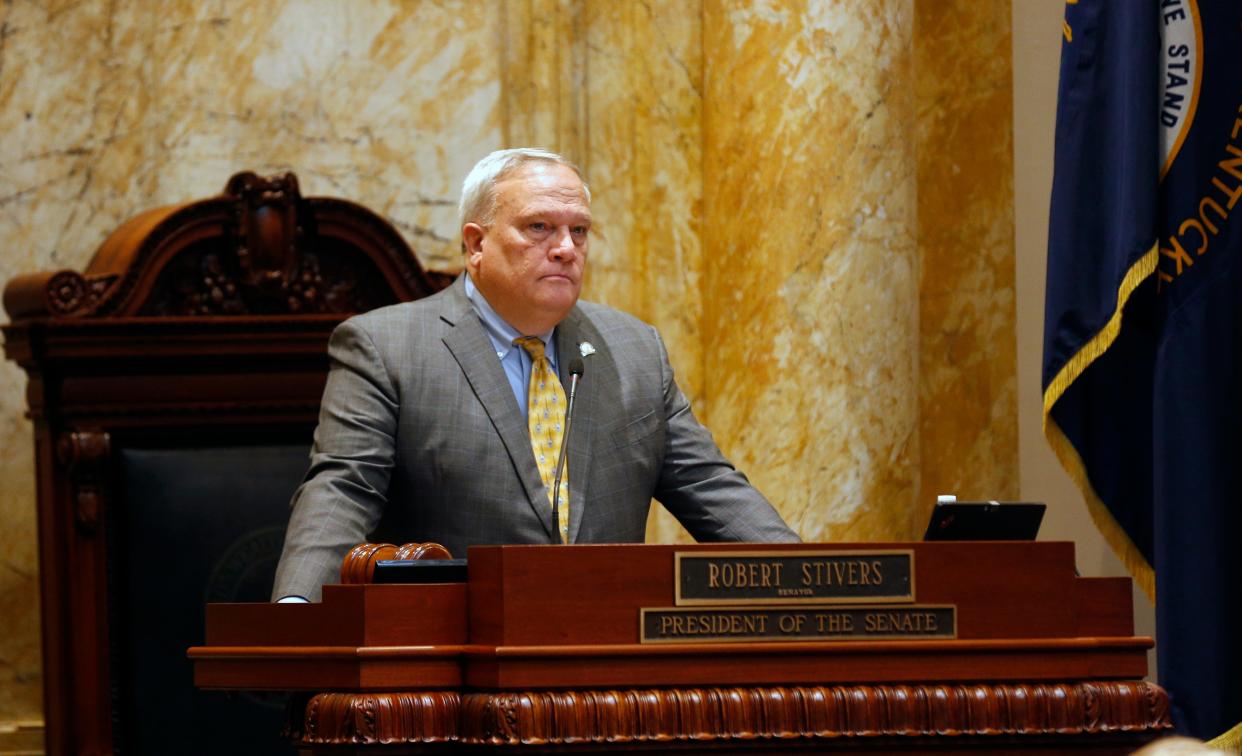

But GOP leaders promoted the budget as fiscally conservative. Senate President Robert Stivers, R-Manchester, called it “one of the best budgets ever proposed or ever drafted.”

Legislators also clashed over the process: Democrats and other critics said rushed timelines did not allow enough public input into the budget process.

Here’s a look at how the budget is made and what advocates and experts are saying about transparency:

How big is Kentucky's budget?

No matter how you look at it, Kentucky’s budget is big.

All told, the latest budget just passed totaled around $137 billion, with an additional $3 billion in one-time spending, according to the Legislative Research Commission.

The budget is not just one document. It’s made up of separate bills that address different parts of state operations.

The largest portion of the state budget is called the executive branch budget. Totaling more than $100 billion, it covers the operations of Kentucky’s main state agencies, like the cabinets for public protection and health and family services.

The documents themselves are voluminous, totaling more than 300 pages.

That complexity is one reason critics said the process should have allowed more time for lawmakers and advocacy groups to understand and debate budget details.

Where does the money come from?

The money for the state budget comes mainly from taxes.

Kentucky collects over 50 different kinds of taxes, including personal and corporate income taxes, property taxes and sales taxes.

The state brought in nearly $1.2 billion from taxes in March, with an additional $127 million coming in from fuel taxes and other transportation-related taxes and fees.

Kentucky also uses funding from federal sources, lawsuit settlements, and other fees the state collects. The state can use debt to pay for projects by issuing bonds.

A nonpartisan group of economists, the Consensus Forecasting Group, advises budget planners about projected revenue so they know how much they have to spend.

Money also comes from the federal government — just over 40% in the budget passed this year, according to the Legislative Research Commission.

Are more Kentucky income tax cuts on the way?

In 2022, the legislature passed a bill to set up an income tax “trigger” system.

Legislators always have had the power to change the state’s income tax, but the system set up in 2022 created a formula tying tax cuts to spending and revenue targets.

If the state meets certain revenue and spending requirements, the legislature can adopt a 0.5% income tax reduction.

When the system started, the income tax was 5%, and it dropped to 4% at the start of this year.

The state failed to meet the requirements for a drop at the start of 2025, but GOP leaders say this year’s revenue and spending numbers will likely trigger a drop to 3.5% starting in 2026.

House Speaker David Osborne, R-Prospect, expects the state will take at least a decade to drop down to a 0% tax rate.

It’s also likely the budget passed this year will trigger additional cuts in 2027 and 2028.

That’s due, in part, to a bill passed this year that excludes spending on projects funded from the state’s rainy day fund, also called the Budget Reserve Trust Fund, from the income tax calculations.

That means the $3 billion in a one-time spending passed this year will not count toward determining whether the state meets its tax-cut targets.

Some are critical of that decision.

“The legislature moved the goal posts on its own formula to trigger tax cuts by suspending the law to ignore $2.7 billion in spending from the Budget Reserve Trust Fund, mainly on infrastructure and specific local projects,” said Pam Thomas, a senior fellow at the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

“At the same time, the enacted budget fails to adequately fund education, child care, housing, teacher and state employee raises, and other needs, despite additional funds being available,” Thomas said. “And this is all because the General Assembly seems to be prioritizing cutting taxes over meeting the critical needs of Kentuckians.”

Many Democratic legislators agreed.

“We have decided as a body our top priority is to hit these artificial triggers so we can cut the income tax,” said Rep. Chad Aull, D-Lexington, during a House budget debate. “It’s not our schools, it’s not our kids, it’s not the citizens of the Commonwealth of Kentucky.”

But GOP budget leaders said the exclusion of one-time expenditures from tax calculations makes sense.

“We need to separate out one time from recurring. They are funded separately. They need to be handled separately and have separate considerations,” said Rep. Jason Petrie, R-Elkton. “There's no hook for next-term appropriations … so we don't have to budget for those items into the next cycle.”

Is the governor’s budget still relevant?

Traditionally, the governor proposes the first draft of the state budget in January, and that serves as the main working document for the budget.

That made sense, because the governor heads up the executive branch, by far the largest portion of the state budget. His team would use information submitted by state agencies to craft the spending plan.

But Republican leaders upended that tradition in 2022 when they introduced their version of the budget before Beshear could release his.

Beshear decided to take no chances this time around, releasing his version of the budget in December 2023, just one week after he had been inaugurated for his second term.

But it’s not clear that Beshear’s early release made any difference in getting his budget priorities enacted. Among those items the legislature nixed were a universal prekindergarten program, an additional pension check for state retirees and across-the-board raises for teachers and other school employees.

Instead, the House version of the budget, introduced in January, served as the key working document.

Republican leaders Senate President Stivers and House budget chairman Petrie said they used budget subcommittee meetings during the legislative off-season between sessions to hear testimony about the state’s budget needs.

What about pensions?

Pensions for Kentucky’s retired state employees and teachers are among the worst-funded in the nation — but better off than they were six years ago.

For many years between 2003 and 2016, the state did not put enough money into the system, resulting in a ballooning “unfunded liability,” meaning the funds were on track to fall short of anticipated costs for pension payments.

This year, GOP leaders included over $700 million to help reduce Kentucky pension plans’ unfunded pension liabilities, as well as the funds needed to meet normal pension obligations.

“It's turned around. It can take a long time to get to where we need to get, but we are clearly on a path we want to be,” said David Eager, the executive director of the Kentucky Public Pensions Authority. “I think it’s a real tribute to what the legislature has done in terms of additional funding.”

Still, some state retirees were disappointed that the legislature did not find additional money for a “13th check.”

Members of the Kentucky Employees Retirement System last got a cost-of-living adjustment in 2011, and Gov. Andy Beshear as well as the Senate version of the budget proposed an additional check this year to help retirees.

However, the House budget did not include that additional check and the proposal ultimately failed.

Is the budget process transparent?

This year, Democrats and other observers criticized the lack of transparency surrounding the budget process.

Critics say the quick turnaround between the introduction of budget bills and votes on those bills prevented the public from providing feedback.

In March, the League of Women Voters of Kentucky called on legislators to allow at least 24 hours between the posting of budget bills and final floor votes on them.

But the Senate voted on the final budget on the same day the bill was filed, and the House voted on it the next day, the final day of the legislative session before breaking for the veto period.

“We're talking about 258 pages of legislation. It's hard for journalists, citizens, even legislators to go through 258 pages in that brief timeframe,” said Becky Jones, a first vice-president with the League of Women Voters of Kentucky.

“What would work is if each chamber would allow a full day between the free conference committee report, so members could look at it, digest it — citizens, journalists might have a chance to look at and digest it,” Jones said.

Advocacy groups face challenges too.

“The centralized and opaque nature of the current budget process makes it difficult for Kentuckians to weigh in,” said Adrienne Bush, the executive director of the Homeless and Housing Coalition of Kentucky.

The last-minute release of the bills “means people are still sorting out details and implications well after passage,” Bush said.

But Kentucky is not alone in the last-minute rush to finalize budget documents, said William Glasgall, a senior director at the Volcker Alliance, a think tank focused on the public sector. That’s common in many states and even the U.S. Congress.

The final conference committee meetings where Senate and House budget leaders hammer out differences do not have to be open to the public under the state’s open meetings law, said Mike Wynn, public information officer for the Legislative Research Commission.

The public’s lack of access to those meetings has pros and cons said, said Vladimir Kogan, a professor of political science at Ohio State University, who called budget transparency “a double-edged sword.”

“When there's less transparency … interest groups can sneak stuff in that nobody catches until it's too late,” Kogan said.

But it’s much harder for politicians to compromise if high-stakes budget meetings are open.

“Because when people are watching, all the incentive is to grandstand and pontificate and position-take,” and that takes away space for compromise, Kogan said.

The process is also too complex to handle entirely in open meetings, Republican lawmakers have said.

“Now there's no way you're going to sit down and sit there and go through everything in an open committee … because it's so long, complex and voluminous. That's not an open-style meeting,” Senate President Stivers told reporters earlier this year.

Jim Waters, the president of Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, a free-market think tank, said he believes transparency around the budget process has increased in recent years but still more is needed.

“We still have a process that that does not give rank-and-file legislators as much time as we would like to see for them to look at the budget before there's a vote taken,” Waters said.

“When you're talking about how taxpayer dollars get spent … I don't think you can be too transparent.”

More: Kentucky to use lottery for medical marijuana business licenses. Here's how it will work

Reach Rebecca Grapevine at rgrapevine@courier-journal.comor follow her on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @RebGrapevine.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Kentucky legislature state budget plan to spend $137 billion